FRESH AIR

Misunderstanding the Middle East in the wake of the Iran-Saudi deal

March 29, 2023 | Oved Lobel

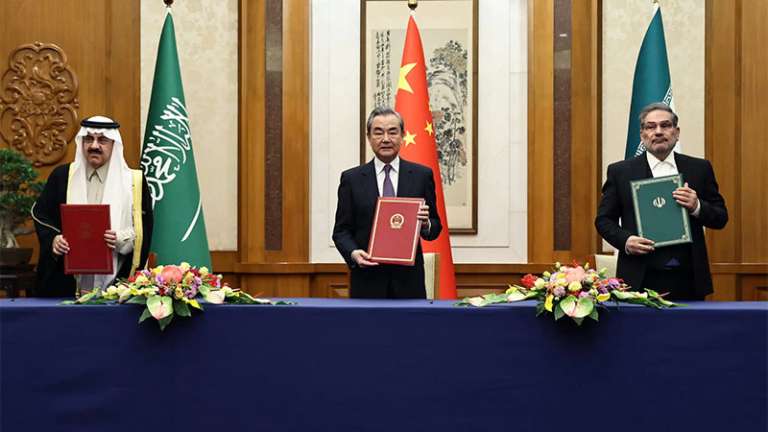

The recent announcement of a deal, brokered under Chinese auspices, to restore official diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran has produced a flurry of panicked commentary in both the US and Israel. There are recriminations in both countries about “who lost Saudi Arabia” and what this will mean for Israel’s relations with the kingdom and the broader “anti-Iran axis”, as well as what this portends for US influence in the region.

This commentary seems to result from a misunderstanding of US policy priorities in the Middle East; ignorance of the long-standing Gulf-China relationship and the chronology of events leading up to this most recent Saudi-Iran rapprochement; and a false belief in an anti-Iran axis in the Gulf.

All of this on top of the fact that the agreement, if implemented, would merely return the region to the status quo ante of 2016, when Saudi Arabia executed Shi’ite cleric Nimr al-Nimr and Iran allowed demonstrators to attack the Saudi embassy in response. Structurally, nothing will change: Iran will remain a threat to Saudi Arabia as the regime continues to try to export its revolution and dominate the Middle East. And given the reported conditions of the agreement, it is unclear whether or how it would be implemented.

A blow to the US?

As articulated by US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan and now Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Arabian Peninsula Affairs Daniel Benaim in Foreign Affairs in May 2020, and since reiterated at every level of the Administration countless times, de-escalation between Saudi Arabia and Iran via diplomacy and dialogue has actually been a central US foreign policy goal in the Middle East since the Obama Administration. Such de-escalation is seen in Washington as a key step towards “rightsizing” the US military presence in the region.

Saudi Arabia began laying the groundwork for these normalisation talks via Iraq in October 2019 after both received the green light from Washington, and they have been supported rhetorically and practically every step of the way by the US.

That the talks culminated under Chinese auspices may strike some as less than ideal, but it’s important to remember that the Biden Administration does not believe in zero-sum competition with China. It has openly called on China to use its relationships with other adversarial powers to bring about what, in the Administration’s view, are mutually beneficial diplomatic outcomes. Indeed, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken praised the agreement and the Chinese role. An Axios report, citing two senior US officials, claims the Saudis kept the US apprised of the negotiations from the start.

Furthermore, there is no information indicating that China actually did anything beyond providing a platform for all three countries to send a message to the US. While this was important symbolically for all three, it seems clear China has no interest in offering either carrots or sticks to change any country’s behaviour and therefore little serious interest in supplanting the US role in the region for the time being. Unless evidence emerges of concrete Chinese guarantees to uphold the agreement, its political role in the Middle East is likely to remain minimal.

Ending the IRGC’s jihad in Yemen?

The Saudi-led intervention to try to halt the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) jihad against the Yemeni Government ended in strategic failure in 2018, when the US and international community blocked an assault against the Houthis in Hodeidah and entrenched Houthi control of the port. This earned the Houthis tens of millions of dollars and enabled them to redeploy reinforcements to other fronts. Since then, Saudi Arabia has been desperately trying to extricate itself from the war, including announcing multiple unreciprocated unilateral ceasefires, which the IRGC has answered with escalation at every turn. A strategically disastrous ceasefire in mid-2022 ended the rollback of Houthi battlefield gains and allowed them breathing space to rearm, recruit, finance themselves and redeploy.

If, as reported, part of the normalisation agreement is predicated on the IRGC ceasing to arm the Houthis, who actually act as an arm of the IRGC themselves, then this is an unworkable and unserious condition.

In the first place, Iran has never admitted to arming the Houthis. Secondly, the plethora of smuggling routes by land, sea and air ensure there’s no possible way to monitor compliance. The US and its allies interdict very few of these shipments.

In addition, the IRGC seems to have established at least partial local manufacturing capability for its missiles in Yemen.

It is possible the IRGC will give the Saudis a “decent interval”, like the Communists did for the Americans in Vietnam, to withdraw all support and abandon their local allies before relaunching an offensive to conquer the country. If the Saudis do not intervene to save Mareb again, for instance, perhaps they themselves will not be bombed as they have been repeatedly from Yemen over recent years.

But the jihad of the IRGC and their local organ, the Houthis, is non-negotiable, so regardless of the timeframe, the Houthis – Yemen’s Taliban – will continue to try to take total control of the country as part of the IRGC’s larger regional jihad. And after that, the IRGC, surrounding Saudi Arabia on three sides, would return its attention to undermining the kingdom itself.

How we got here

The origin of the Iran-Saudi deal can be traced to September 14, 2019. On that day, Iran launched a brazen, direct attack using drones and missiles against Saudi Arabian oil facilities in Abqaiq and Khurais. In response, then US President Donald Trump did nothing, despite increasing Saudi pressure and the fact that the entire US-Saudi relationship had been predicated on the US responding to precisely such an attack. With the realisation that the Trump Administration, despite its rhetoric on Iran, had decided to saw off the limb onto which the Saudis had crawled under the assumption that the US would defend them, the Saudis understood their only option was to de-escalate with Iran, a process they began approximately two weeks later.

As talks progressed throughout 2021 via Iraq and Oman, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman said, “Iran is a neighboring country, we all aspire to establish a good and distinguished relationship with Iran.”

Well, they certainly won’t ever have that. As documented by Kim Ghattas in her book Black Wave, the Saudis previously pursued détente with Iran as soon as Iranian regime founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini died in 1989. Riyadh sustained these efforts despite Iranian terrorist attacks in Saudi Arabia and across the world, despite revelations about Iran’s nuclear program and despite the assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister and Saudi darling Rafiq Hariri in 2005 by the IRGC’s Lebanese branch Hezbollah. This one-sided détente only began to collapse after Hezbollah’s takeover of Beirut in 2008 and the Houthi conquest of parts of Saudi Arabia in 2009.

It will be no different this time around. Though the Saudis may have no choice, restoring diplomatic relations will not buy them protection any more than it did in previous decades. It is not as if official relations with Iran protect any other country from IRGC hostage-taking, terrorism, piracy, cyber-attacks or other malign conduct.

The Saudis even seem to be tacitly offering money to Iran to not attack them, judging from the recent statement by Saudi Finance Minister Mohammed Al-Jadaan that “There are a lot of opportunities for Saudi investments in Iran. We don’t see impediments as long as the terms of any agreement would be respected.” However, such a protection racket would not change the Iranian regime’s conduct for long, if at all.

The Saudi-China relationship

There is a tendency in Western commentary to interpret any interaction that a particular partner has with an adversarial power as a direct response to a specific policy, generating a lot of handwringing and partisan recriminations. This, however, is not the most useful framework for understanding international affairs, especially in the Middle East.

The Saudi-China relationship traces back to the 1980s, when the kingdom began purchasing ballistic missiles from China. That relationship has only grown as China’s economy expanded, with China becoming Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner and oil importer. As Sullivan and Benaim wrote in Foreign Affairs, “As Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (known as MBS) seeks to modernize the Saudi economy, he will undoubtedly deepen ties with China—it’s the sensible thing for him to do.”

Alongside this economic relationship, Saudi Arabia has developed a military relationship with China to acquire weapons and capabilities the US won’t provide. This includes a ballistic missile manufacturing facility built with China’s help, discovered in 2018 but the construction of which seems to have begun in 2013, as well as a deal to jointly produce drones in the kingdom signed in early 2017, and a further drone development and production deal signed in early 2022. China has also been one of the countries helping Saudi Arabia pursue a potential nuclear program for over a decade.

Saudi Arabia, like most of the Middle East, has always in practice maintained and sought relations with both the US and its adversaries for decades. As is obvious from the chronology above, these relationships have little to do with any specific US administration or policy.

There is no anti-Iran axis

The restoration of official diplomatic ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran probably has no implications for the hopes for future normalisation between Saudi Arabia and Israel because there is no linkage between the two.

The Abraham Accords, for example, painted by some as part of an anti-Iran alliance, was to a large degree actually an extension of the UAE’s diversification strategy and “zero problems with neighbours” policy over the last five years. It followed Abu Dhabi’s diplomatic normalisation with the lynchpin of Iran’s “resistance axis”, Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, as well as with previous adversaries Qatar and Turkey and, more recently, Iran.

The UAE has had a partial partnership with Iran, acting as its primary sanctions-busting hub and occasionally running political interference on its behalf. For instance, in May 2019, when Iran launched its tanker war in UAE ports in response to the US “maximum pressure” campaign, the UAE refused to blame Iran despite Trump Administration officials openly doing so.

Worse, it pushed back against the US from Moscow, with which it has a deep strategic military and political partnership, and then, instead of siding with the Americans against Iranian attacks, it promptly went to Iran to engage in “maritime security talks”. As Anwar Gargash, UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed’s (MBZ) diplomatic adviser, announced in July 2022 while fully restoring diplomatic relations with Iran, the UAE is “not part of any regional axis” against Iran. Similarly, potential Saudi relations with Iran are unrelated to potential relations with Israel.

It has been widely understood for some time amongst the Gulf states that, regardless of who is in power in Washington, the US is not that interested in containing Iran, and thus there is no appetite for risky anti-Iran action in the Gulf that might provoke a dangerous Iranian response with no guarantee of US protection or retaliation. This is why the UAE publicly welcomed “joint efforts to de-escalate tensions and for renewed regional dialogue” in Jan. 2021. It is difficult to imagine a reality in which the UAE would participate in kinetic action against Iran or even encourage it barring a sea change in US policy.

The same is true of Saudi Arabia, whose Crown Prince was humiliated by Iran after the direct attacks in 2019 as well as strategic defeats in Lebanon, Syria and Yemen – in large part due to US choices.

In Jan. 2018, I wrote that “[Israel] is currently entirely isolated on the Iranian issue, with the possible exception of Saudi Arabia, a dangerous partner that has time and again displayed reckless incompetence when it comes to dealing with Iran.” That reckless incompetence has caught up with Saudi Arabia, and Israel is, as ever, largely on its own when it comes to Iran.

Tags: China, Houthis, IRGC, Iran, MBS, MBZ, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Xi Jinping, Yemen

RELATED ARTICLES

US Middle East strategy amid regional instability: Dana Stroul at the Sydney Institute

Antisemitism in Australia after the Bondi Massacre: Arsen Ostrovsky at the Sydney Institute