UPDATES

Sudan normalises relations with Israel

October 29, 2020 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

10/20 #04

This Update analyses the implications of the announcement over the weekend that Sudan would be following the UAE and Bahrain and normalising relations with Israel. (The full statement by Israel, Sudan and the US is here; Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s comment on this announcement are here.)

We lead with the always knowledgeable and insightful Israeli journalist, and frequent AIJAC guest, Ehud Yaari. He reviews the US-led multilayered, multiparty negotiations over the past year that led to the normalisation breakthrough with Sudan. He also looks at the domestic developments and tensions within Sudan which made that breakthrough possible, and who in the complicated ruling circles of that country was in favour and against normalisation, and why. For all Yaari’s analysis, based on his unsurpassed contacts across the region, CLICK HERE. Meanwhile, Yaari, together with colleague Michael Singh, also published an article discussing the prospects of Indonesia developing ties with Israel in the wake of the recent normalisations.

Next up is Raphael Ahren of the Times of Israel. The focus of his piece, published just before the Sudan normalisation was actually announced, is the significance of this deal for Israelis and how it differs from last month’s UAE and Bahrain normalisation deals. He notes that, unlike the UAE and Bahrain, Sudan was an actual enemy which physically fought Israel in the past, and is notorious as the site of the Arab League’s “three Noes” declaration of 1967, rejecting any negotiations, recognition or peace with Israel. For additional important insights into what Sudanese relations mean for Israel and Israelis, CLICK HERE. Ahren also had a piece noting that full relations between Israel and Sudan may take some time to be worked out, despite the announcement on the weekend.

Finally, Israeli Arab affairs expert Yoni Ben Menachem explores why the Israel-Sudan deal is a significant setback for Hamas and its patron Iran. He reviews the recent history of Sudan serving as a key transit point for smuggling Iranian weapons into Gaza for Hamas via Egypt, and how Israeli forces even struck such weapons convoys inside Sudan a number of times between 2009 and 2014. He then explores how Sudan came to change its approach subsequently – already under dictator Omar al-Bashir pulling away from its alliance with Iran, and then completely reversing it after he was overthrown in April 2019. For the details of this key strategic implication of the Sudan-Israel deal, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne’s tweet welcoming the Israel-Sudan peace deal.

- Sudanese leader Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan says the Israeli normalisation deal serves Sudan’s interests and is not the result of US “blackmail”.

- Another Sudan-Israel relations analysis from Israeli academic Dr. Haim Koren.

- More comment on the significance of Sudan’s changing alignment from American pundit Jonathan Schanzer. Plus a good editorial on the subject from the Wall Street Journal.

- Well-known Israeli journalist Ben Caspit visits Dubai and finds enormous potential for UAE-Israel economic relations there.

- Jonathan Spyer and Benjamin Weinthal make the case against the US selling advanced F-35 aircraft to Qatar, as has been proposed.

- A posthumously published article by the late Ambassador Richard Schifter, veteran US diplomat and AIJAC collaborator, on the UN’s counterproductive stances on Israeli-Palestinian relations, written together with Daniel Mariaschin.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- AIJAC’s statement welcoming the Sudan-Israel normalisation deal.

- Oved Lobel reports on Iran’s efforts to step up influence operations and cyber-mischief in the lead-up to the US election.

- Video of AIJAC’s webinar with former Israeli National Security Advisor Maj. Gen. (ret.) Yaakov Amidror on the subject of “Israel’s changing security environment”. A short excerpt of the webinar featuring Amidror speaking about Israel’s struggle against the Hezbollah missile threat is here.

The Sudan Agreement: Implications of Another Arab-Israel Milestone

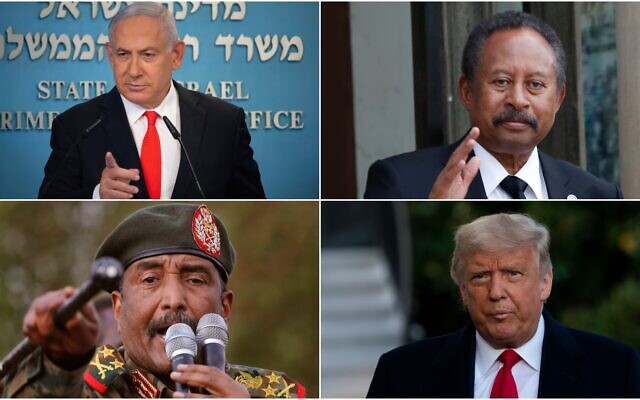

US President Donald Trump speaks with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on the phone about a Sudan-Israel peace agreement, in the Oval Office on October 23, 2020 in Washington, DC. President Trump announced that Sudan and Israel are making peace. (Win McNamee/Getty Images/AFP)

When the White House announced an agreement for mutual recognition and normalization of relations between Sudan and Israel on October 23, it represented the successful conclusion of a multilayered, multiparty package deal that had been negotiated intensively for over a year. The main trigger for this breakthrough was the Trump administration’s decision to delist Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism, a designation the country had held since 1993. Given Sudan’s severe economic crisis, the authorities who toppled the dictatorship of Gen. Omar al-Bashir and took power in April 2019 have been desperate to end U.S. sanctions, attract investments, and open prospects for relieving around $60 billion in debt.

As part of the negotiations, the Sudanese government has deposited $335 million in an escrow account to compensate victims of the 1998 terrorist attacks on the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania and the 2000 attack on the USS Cole in Aden. According to local authorities, Khartoum has been assured that no further claims are forthcoming. Lifting the sanctions is the next step in the process, to be followed by talks with the IMF and resumption of American aid.

Alongside consistent U.S. pressure to link the terror delisting with peace moves toward Israel, the preliminary negotiations benefited from behind-the-scenes encouragement and financial aid commitments by the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, as well as tacit backing by Sudan’s neighbor, Egypt. Khartoum’s decision could also accelerate similar normalization efforts by other Arab countries, though such progress will probably be more gradual than the “big splash” peace agreements with the UAE and Bahrain.

PAST HOSTILITIES AND SECRET TALKS

Khartoum’s decision differs from the Emirati and Bahraini normalization moves in another notable respect: Sudan and Israel have a history of past military clashes and other hostile behavior. For example, Sudanese companies fought alongside the Egyptian army in the 1948 and 1967 wars. Shortly after the latter conflict, Khartoum hosted the summit at which the Arab League adopted its infamous “three no’s” policy—no peace, no negotiations, no recognition of Israel. And during the 1973 war, Sudan sent an expeditionary force to the Suez front, though only after a ceasefire had been reached, rendering the deployment largely symbolic.

Meanwhile, Israel began helping the insurgency in southern Sudan as early as 1968, offering equipment and training to the Anyanya rebels and, later, the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) up until South Sudan won its independence in 2011. Israeli forces also mounted several air raids against Sudanese munitions storage facilities in 2009-2012, attempting to curb Bashir’s practice of allowing Iran to ship weapons through his territory to Hezbollah and Hamas.

Despite these hostilities, Israel and Sudan pursued intermittent secret contacts for decades prior to the current deal. They began in the mid-1950s with Sadiq al-Mahdi, the leader of the powerful National Umma Party who was engaged in a struggle with President Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt at the time. (Interestingly, the eighty-five-year-old Mahdi has since become the most vocal domestic opponent of the current normalization drive, presumably in a bid to reverse his political marginalization.) Later, Israel secretly cooperated with President Jaafar Nimeiri, who shook hands with Prime Minister Menachem Begin during Anwar Sadat’s 1981 funeral in Cairo—an event that other Arab leaders boycotted due to Begin’s presence. Israel also obtained quiet help from Khartoum in evacuating Jews from Ethiopia.

Under Bashir, Khartoum sought contacts with Israel after breaking with Iran, distancing from Turkey, and joining the Saudi war effort in Yemen. After his ouster, Sudan resumed quiet dialogue with Israel, leading to the first public meeting between Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Sovereignty Council head Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan this February in Uganda.

DOMESTIC REPERCUSSIONS FOR SUDAN

Sudanese Gen. Abdel-Fattah Burhan, head of Sudan’s ruling sovereign council, speaks during a military-backed rally in Omdurman district, west of Khartoum, Sudan, June 29, 2019. (AP Photo/Hussein Malla, file)

The Uganda meeting stoked a stormy debate in the Sudanese press and social media about the pros and cons of reconciliation with Israel. The prime mover in favor of speedy normalization was the council’s vice president, Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known by his nickname Hemeti. He commands the Rapid Support Forces, a 70,000-strong military organization that is separate from the Sudanese army and sprang out of the militias formed during the long Darfur conflict. These irregulars were often blamed for committing atrocities, but Hemeti denies the accusations and was not among those charged at the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

While Burhan remained tight-lipped about normalization in public, Hemeti campaigned for it at gatherings all around the country, arguing that engagement with Israel was in Sudan’s best interests. The main objections came from Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, who heads a civilian cabinet created by the partnership formula reached between the military chiefs and the “Freedom and Change” political coalition. As late as September, Hamdok was still attempting to delink the Israel issue from Sudan’s U.S. terrorism designation. Yet his position softened once Washington firmly conditioned the end of sanctions on peace with Israel.

Meanwhile, developing cooperation between Hemeti and Hamdok brought about a breakthrough in efforts to restore internal peace, with rebel groups represented by the Sudan Revolutionary Front signing the Juba Agreement early this month. All of these groups support rapprochement with Israel and oppose political Islam. Abdel Wahid al-Nur—the Paris-based leader of the strongest rebel faction, the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM), which is still negotiating its own peace agreement—has already made a public statement welcoming normalization. Another key rebel figure, Abdelaziz Hilu of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North (SPLM-N), is expected to follow suit.

Hamdok, an experienced economist, apparently concluded that he could use the practical benefits of normalization to overcome opposition from communists, Nasserites, Baathists, and Islamists. Indeed, these groups have not managed to stage meaningful protests against the deal so far, nor have they left the government.

Through Foreign Minister Omar Qamar al-Din, Hamdok is now promising that the Israel deal will be ratified by parliament. Yet the legislative assembly that was supposed to be formed for the transitional period until elections in 2022 has not been established. According to arrangements between Sudan’s military chiefs and civilian politicians, a joint meeting of the Sovereignty Council and the government’s ministers may exercise the powers of the absent parliament. This mechanism may allow Israel and Sudan to activate their coming normalization protocols without a parliamentary vote.

For now, Sudan has granted Israel the right to use its airspace for shorter flights to Latin America—one of Netanyahu’s longstanding priorities for boosting trade ties. The Sudanese are also seeking Israeli know-how and technologies for agriculture, among other sectors. With drastic reforms and substantial investments, the country could eventually become a breadbasket for the Arabian Peninsula and beyond—the Emiratis and Saudis have already expressed great interest in this potential. Moreover, cheap electricity from Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam, only a few miles from Sudan’s border, would further enhance the prospects of igniting an economic recovery in the not-too-distant future.

It is unclear at the moment how quickly Israel and Sudan will sign each of the individual protocols and establish mutual embassies. Yet it is safe to assume that Burhan is keen to move as fast as possible—certainly before January, when a new president may enter the White House.

PROSPECTS FOR FURTHER NORMALIZATION DEALS

Most Arab states are waiting for the results of the U.S. election before making any public overtures toward Israel. Morocco, Oman, and Qatar are weighing the possible advantages of upgrading their relations—though all three may be overtaken on the bumpy road to Jerusalem by Djibouti, whose president has been urged by the UAE to consider a move. Eventually, Abu Dhabi’s great influence down the East African coast may lead to some form of cooperation between Israel and the two de facto states of Somaliland and Puntland. Israel will also intensify efforts to establish relations with the Muslim-majority states of the Sahel, including Mauritania, which recognized Israel in 1999 but severed formal relations a decade later.

Ehud Yaari is a Lafer International Fellow with The Washington Institute and a commentator for Israeli television.

‘Yes, yes, yes’: Why peace with Khartoum would be true paradigm shift for Israel

By RAPHAEL AHREN

Times of Israel, 23 October 2020

The big, poor African state and the small, rich Gulf monarchies couldn’t be more different; for a start, unlike Bahrain and the UAE, Sudan actually went to war against Israel

Yes to removal of Sudan from the US list of state sponsors of terror. Yes to a billion-dollar aid package. And yes to normalization with Israel?

The remarkable tale of Sudan turning from a symbol of the Arab world’s rejection of the Jewish state, into its latest potential peace partner, could be summed up by referring to three no’s that, in the span of 53 years, look set to become three yes’s.

Many Israelis still associate Khartoum with the “Three No’s” — “No peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with Israel” — formulated by an Arab League summit held in the Sudanese capital shortly after the end of the Six-Day War in 1967.

Now, after months of pressure from the US administration, the culmination of efforts to get the Northeast-African Arab country to normalize relations with Israel appears closer than ever, perhaps just days away.

Earlier this week, the transitional government in Khartoum agreed to pay $335 million in compensation to the victims of the 1998 bombings of two US Embassies in Africa (Sudan didn’t perpetrate the attacks, which killed 224 people, but granted asylum to the terrorists). In exchange, US President Donald Trump vowed to remove the country from its lists of state sponsors of terrorism, where it has been since 1993.

Together with a massive financial aid package for the struggling country — the US has reportedly offered $800 million in aid and investments, but Sudan demands some $3-4 billion — the removal of the terrorism designation is largely seen as a precursor to a normalization deal with Israel.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on Thursday spoke with Sudanese Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, applauded his “efforts-to-date to improve Sudan’s relationship with Israel, and expressed hope that they would continue.”

According to Hebrew media reports, Jerusalem and Khartoum will announce the establishment of diplomatic ties over the weekend or early next week.

Other reports indicated that Hamdok is willing in principle to normalize relations with the Jewish state, but insists his country’s yet-to-be-formed transitional parliament must first approve such a move.

Thus a Sudan-Israel deal seems to be a question of when, and not if.

Six Sudanese army companies fought nascent Israel in 1948

When that moment arrives, it would not only be another major foreign policy achievement for Trump and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu nor merely another encouraging step on Israel’s path to fuller integration in the region.

Rather, it would mark a paradigm shift in Middle East politics. For one thing, Sudan, as opposed to Israel’s new friends in the Gulf, has a history of military conflict with Israel. And unlike the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain, it has not been long known to clandestinely cooperate with Jerusalem in various areas, including security and trade.

To be sure, the August 13 bombshell announcement that the UAE had agreed to establish full diplomatic relations with Israel was historic. It made public the hitherto covert alliance between Jerusalem and the Gulf states. It shattered the Palestinian veto over Arab ties with Israel.

And it paved the way for other Sunni Gulf nations to follow suit: Bahrain has already signed an agreement, in a move in turn welcomed by Saudi Arabia and Oman, who could also be in line soon for normalization.

But Sudan is a whole new ball game, not better or worse, but emphatically different.

General view of the closing session of the Khartoum Summit Conference of Arab Heads of State in the Sudanese Parliament House on, Sept. 1, 1967, which issued the famous “three noes”. Addressing the assembled Arab chiefs is Sudanese President Ismail al-Azhari. (AP Photo/Claus Hampel).

For one, a warm yes from the capital known for the “Three No’s” would likely have a tremendous psychological impact on Israelis. “Those who used to reject us so bitterly have finally embraced us,” many might reasonably say.

More importantly, a peace accord with Khartoum would actually be that — a peace accord. The UAE and Bahrain — countries that share with Israel worries about Iranian belligerence and hence have long flirted with normalization — were never at war with Israel.

Sudan, on the other hand, has been a bitter enemy of the Jewish state since its founding. During the 1948 War of Independence, six Sudanese army companies joined the Egyptians in fighting the nascent Jewish state.

The animosity continued for seven decades. Until 2016, Sudan was a staunch ally of Iran, helping the Islamic Republic smuggle rockets and other weapons to Palestinian terror groups in Gaza. This prompted Israel to repeatedly bomb military facilities in the country, according to foreign reports.

A bridge between Arabs and Africans

Sudan’s regime is very different from those of the UAE and Bahrain. It’s on its way to becoming a democracy, while the two Gulf states will continue to be ruled by autocrats for the foreseeable future.

And Khartoum’s geopolitical situation could be very interesting for Israel, said Irit Bak, head of African Studies at Tel Aviv University.

“We now have diplomatic relations with most African countries, and an important country like Sudan, which is one of the biggest countries in Africa and also is kind of a bridge between Africa south and north of the Sahara, between Arabs and Africans in Africa, could be a huge benefit… in an effort to bring more diplomatic support to Israel in international forums,” she told the Jerusalem Press Club on Thursday.

More than 40 million Muslims

With a territory of 1,861,484 square kilometers (718,722 square miles), Sudan is 22 times bigger than the UAE and Bahrain together.

It has a population of 45 million, most of whom are ethnic Sudanese Arabs. The UAE, by contrast, has only 10 million inhabitants, of whom only 12 percent are Emiratis. (Bahrain has a population of 1.5 million, less than half Bahrainis.)

But bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better, and certainly not in economic terms. The UAE (GPD per capita: $68,600) and Bahrain ($49,000) are known as major international financial hubs. Sudan ($4,300) is known for an economy in shatters after decades of war and internal strife.

What about people-to-people relations? Emiratis seem genuinely enthusiastic about ties with Israel, and Bahrainis have largely welcomed their government’s agreement with Jerusalem as well, despite some protests by its Shiite population. Both countries have small but well-integrated Jewish communities that are supported by the government.

With Sudan, the situation is more complicated. Despite the recent establishment of a handful of pro-Israel groups advocating for normalization, hatred toward the State of Israel is still widespread.

According to Bak, the Africa scholar, a peace accord with Israel would be “quite controversial between many streams in Sudan politics and society” and may create “antagonism amongst many populations or civil societies in Sudan.”

The government-affiliated Islamic Panel of Scholars and Preachers, which advised the government on religious questions, ruled last month that Islamic law prohibits ties with Israel (a stance contradicted by one leading cleric, however).

In this 1950 handout photo, provided by Tales of Jewish Sudan, a Jewish wedding is held in Khartoum synagogue, Sudan. The synagogue was sold in 1987 after most Sudanese Jews left the country and currently is a bank. (Photo courtesy of Flore Eleini, Tales of Jewish Sudan, via AP)

There is no functioning synagogue in all of Sudan; in fact, only one Jewish family remains of what was once a thriving Jewish community.

The normalization process with Sudan will likely be complicated, uneasy and much slower than those with the UAE and Bahrain. But if concluded successfully, Jerusalem would finally have peace with a large and important country that for decades exemplified the Arab world’s war against the Jewish state.

To many Israelis, that may ultimately be even more meaningful than lucrative business deals and the prospect of vacations in luxury hotels.

Hamas Is Very Concerned about Israel’s Normalization with Sudan

Yoni Ben Menachem

Jerusalem Centre for Public Affairs, October 25, 2020

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir welcomes Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh to Khartoum, 2011, (Ikhwan Online)

There is a serious concern among the Hamas leadership that the normalization agreement between Sudan and Israel will paralyze Hamas’ activities in Sudan.

Sudan had previously allowed Hamas to turn its territory into a major smuggling route for weapons from Iran to the Gaza Strip. However, conditions have changed today, and normalization with Israel will commit it to a determined war against all forms of terrorism.

The Hamas movement is very concerned about the declaration of normalization between Sudan and Israel. Sudan, a Sunni Muslim state, has for many years been a convenient setting for the Muslim Brotherhood and the Hamas movement and a vital smuggling route for weapons from Iran into the Gaza Strip because of its location along the Red Sea.

The normalization agreement between Sudan and Israel is a double whammy to Iran and Hamas alike.

On October 23, 2020, Hamas issued a statement condemning the normalization agreement between Sudan and Israel. It expressed its anger and resentment of the agreement, calling on the Sudanese people to “fight all forms of normalization and have nothing to do with the criminal enemy.”

Hamas’ statement warned that the agreement would not bring stability to Sudan, would not improve its situation, “and would tear up Sudan itself.”

A Pariah State

Sudan was a terrorist-supporting state that hosted al Qaeda and its leader Osama bin Laden and even embraced Hamas.

This policy was conducted by General Omar al-Bashir, who ruled Sudan from 1989 to 2019, dispersed the National Assembly, and governed with martial law that applied Muslim Sharia law. In March 2009, al-Bashir was indicted by the International Criminal Court for being criminally responsible for a savage campaign of killing, rape, and pillage against civilians in Darfur. Al-Bashir was deposed in a coup in April 2019.

Israeli Airstrikes in Sudan

More than ten years ago, Israeli intelligence discovered that Sudan served as a major route for transferring weapons from Iran to the Gaza Strip.

According to foreign sources (and confirmed by Israeli security sources over the years), the Israeli Air Force attacked targets inside Sudan several times as part of Israel’s fight against Iran smuggling weapons through Sudan into the Gaza Strip for Hamas.

In March 2009, Time Magazine published reports from Israeli security officials that Israeli planes and unmanned aircraft attacked a Sudanese convoy during the anti-Hamas Operation Cast Lead in Gaza. The convoy consisted of 23 trucks carrying weapons intended for the Gaza Strip.

The Israeli air operation aimed to stop the supply of weapons to Hamas and send a message to Iran about Israel’s precise intelligence and operational capabilities.

Screenshot from video of the destroyed convoy in Sudan. (YouTube, Al Jazeera)

The attack against the arms supply was a complex operation 1,800 miles from Israel that required refueling of the F-16 fighter jets in the air over the Red Sea. The convoy was carrying some 120 tons of Iranian weapons, including anti-tank missiles and al-Fajr-3 rockets capable of reaching 40km (25 miles) and equipped with a 45kg warhead.

Several Iranian civilians and Sudanese smugglers were killed in the strike. A few days before the attack, the United States warned the Sudanese government not to allow the smuggling of weapons from its territory. The Sudanese government ignored the warning, and the Israeli strike came.

However, despite the successful Israeli attack, arms smuggling continued from Sudanese territory to the Gaza Strip.

Yuval Diskin, the head of Israel’s General Security Services, revealed at a government meeting in 2009 that in the months after Operation Cast Lead, 22 tons of standard explosives, 45 tons of raw materials to create weapons, dozens of standard rockets, hundreds of mortar shells, and dozens of anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles had been smuggled into the Gaza Strip.

Egypt was aware of the weapons smuggling from Sudan to the Gaza Strip and also worked to thwart the smuggling during the rule of President Hosni Mubarak. In March 2011, Egypt officially announced that the Egyptian army had stopped five vehicles carrying any weapons from Sudan on their way to the Gaza Strip, and the weapons were seized in the border area between Egypt and the Gaza Strip. The shipment included large quantities of mortar shells, grenades, and explosives that were supposed to be smuggled through the tunnels into the Gaza Strip.

According to foreign sources, in October 2012, four Israeli Air Force planes attacked the Iranian al-Yarmouk plant in Sudan, which produced ammunition and weapons for Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Two people were killed in the attack. According to various reports, Iran had established the factory as early as 2008.

Below are three different satellite photographs of the al-Yarmouk weapons plant. One photograph was taken before the attack when 40 shipping containers were stacked at the factory complex, the second after the explosion, and the third with infrared enhancement.

Satellite Sentinel Project photographs, October 2012.

The Yarmouk base in Khartoum, Sudan, on October 26, 2012. (United Nations, Satellite Sentinel Project)

“The imagery shows six large craters, each approximately 16 meters across and consistent with impact craters created by air-delivered munitions, centered in a location where, until recently, some 40 shipping containers had been stacked,” the Satellite Sentinel Project said in a statement. “An October 12 image shows the storage containers stacked next to a 60-meter-long shed,” it said. “While (Sentinel) cannot confirm that the containers remained on the site on October 24, analysis of the imagery is consistent with the presence of highly volatile cargo in the epicenter of the explosions.”

According to intelligence experts, a large stockpile of Fajr-5 rockets was destroyed in the attack that was supposed to reach Hamas in the Gaza Strip. The stockpile may have also contained medium-range “Shahab-3” ballistic missiles with a range of 1,280 km (800 miles) that were supposed to be stationed in Sudan and threaten Israel.

When Did Sudan Start Working against Hamas?

In 2014, there was a turning point in Sudan when ruler Omar al-Bashir clashed with Iran, claiming that Iran was working to spread the Shiite religion in Sunni Sudan. Sudan expelled Iran’s cultural attaché from its territory and closed Iranian cultural centers on its territory. The Sudanese decision was apparently made following pressure from Saudi Arabia, Tehran’s foe.

The crisis in relations between Sudan and Iran also had an impact on relations with Hamas. Sudan cooperated with Iran in smuggling weapons through its territory to Egypt and from there to the Gaza Strip. The weapons came in Iranian ships that regularly docked in Port Sudan.

In March 2014, IDF naval commandos seized the KLOS-C ship in the Red Sea. The Panama-registered ship, bearing 100 containers of weapons and cement from Iran, was supposed to arrive at Port Sudan. The IDF captured long-range missiles with 200 km ranges that were destined for the Gaza Strip via Hamas’ tunnels.

Weaponry confiscated the IDF after interdicted the Klos-C in the Red Sea. (IDF Spokesman’s Office)

The interdiction occurred 1,500 km (900 miles) from Israel and demonstrated once more Israel’s superior intelligence and operations capabilities in the war against Iranian-Hamas terrorism.

After clashing with Iran, Sudan closed down Hamas offices in its territory and began arresting movement’s operative who had established a terrorist infrastructure in the country.

Following Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s meeting in Entebbe, Uganda, on February 3, 2020, with Sudan’s Sovereign Council Chairman, General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, it was reported that Hamas attempted to establish a branch for intelligence missions in Africa in Sudan.

The Intel Times website reported in July 2020 that the Sudanese authorities arrested in Khartoum Muhammad Ramadan’ Abd al-Gafur, head of the Africa branch of the Intelligence Division of Hamas’ military wing. This is the branch of Hamas that deals with building the organization’s military force through Hamas affiliates in Malaysia, Turkey, and Lebanon.

In light of Hamas’ extensive activity in Sudan in the past, the organization fears that the normalization agreement between Israel and Sudan will include appendixes on the two countries’ war against terrorism, which will tighten Sudanese security officials’ monitoring of Hamas operatives in the country.

Hamas activists still have a presence in the country and are assisted by Muslim Brotherhood activists and opposition figures.

After President Trump removed Sudan from the list of countries sponsoring terrorism, the Khartoum regime is now motivated to portray itself to the world as a country determined to fight terrorism.

The process of normalizing relations between Arab countries and Israel is terrible news for Hamas when it comes to its military activities. The Gulf States are already limiting Hamas’ steps. In Saudi Arabia, 60 Hamas activists are being prosecuted for smuggling money through Turkey to Hamas’ military wing in the Gaza Strip.

Hamas estimates that any Arab or Islamic state that joins the normalization process with Israel will have to commit to the United States and Israel that it will fight terrorism, which means severely harming its military wing operations overseas, in addition to the political harm to the organization being defined as a “terrorist organization.”

In the framework of the peace agreement with Israel, this should also be a test for Sudan – committing to fighting both Shiite and Sunni terrorist organizations, including Hamas, which is on the top of the list due to its past activities. Israel and the U.S. will not give up on this issue, and therefore, Hamas is under considerable pressure.

Yoni Ben Menachem, a veteran Arab affairs and diplomatic commentator for Israel Radio and Television, is a senior Middle East analyst for the Jerusalem Center. He served as Director General and Chief Editor of the Israel Broadcasting Authority.