UPDATES

The psychology of Iran’s rulers and their nuclear plans

February 22, 2012

Update from AIJAC

Feb. 22, 2012

Number 02/12 #06

This Update includes two new pieces by experts attempting to explain how Teheran views the current nuclear standoff – a vital piece of the puzzle if policies are to be implemented to influence the behaviour of Iran’s leaders.

First up is Ray Takeyh of the US Council on Foreign Relations, who points out that the primary reason the leaders of the Iranian regime believe they need nuclear weapons is because, for historical reasons, they both see themselves as the “natural hegemons” of the region, and are a revolutionary regime, whose purpose is to export their revolution to other countries. He notes that, unusually, in Iran the revolutionary ethos has not mellowed into pragmatism, but instead been re-invigorated by a new generation of radical leaders like President Ahmadinejad. Furthermore, their ideology convinces them that the West will always conspire against them, and a negotiated accommodation or long-term coexistence with the West is impossible, leading them to seek their goals through nuclear might. For all of Takeyh’s important insights into the worldview of the Iranian regime, CLICK HERE. Meanwhile, noted Middle East analyst Martin Kramer calls attention to a frightening book highlighting the extent to which Iranian leaders take the irrational elements of their religious worldview seriously.

Another Iran expert, Michael Rubin, makes some similar points, arguing that Washington and other Western leaders are failing to grasp that Teheran does not believe in playing by the rules of Western diplomacy, representing values that it rejects. He notes that even before the 1979 revolution, Iranian diplomacy was characterised by an egotism and self-involvement which made understanding the point of view of interlocutors almost impossible, and that for Iran, diplomacy is “less a system for problem solving than it is an asymmetric warfare strategy.” He argues based on this analysis that only making nuclear weapons overwhelmingly costly can change Iran’s strategic calculations. For the rest of what he has to say, CLICK HERE.

Finally, noted israeli strategic analyst Efraim Inbar gives the mainstream Israeli perspective on where the current nuclear standoff with Iran is today. He says most Israeli officials and analysts are “increasingly exasperated” with the American and European view that Iran is a rational actor that can be dissuaded from going nuclear through sanctions, or contained through deterrence if it does go nuclear. He says Israel has already decided that stopping Iran is urgent, and worth considerable costs and risks to do so, and the primary debate in Israel is between those arguing for more time for covert action, and those saying a military strike should come very soon. Inbar makes a number of other interesting points, and to read them all, CLICK HERE. Another somewhat similar view comes from noted Israeli historian Benny Morris. More on why Israel fears that we are approaching the point of no return on Iran from American strategic analyst Robert Haddick. Finally, the same paper that published Inbar’s view from Israel also published a view from Saudi Arabia about Iran – with an amazing amount of overlap.

Readers may also be interested in:

- For those who didn’t see it in yesterday’s Australian, Daniel Schwammenthal had an excellent article why the argument that a nuclear Iran can be contained and deterred just like the Soviet Union did during the Cold war looks extremely questionable.

- Former long-serving US Middle East mediator Dennis Ross argues now is the time to open up negotiations with Iran, with the sanctions starting to bite. More on Ross’s statements on and approach to Iran is here. However, the Guardian reports that senior US officials doubt the sanctions will be effective.

- An interesting Newsweek report on the development of Obama Administration policy on Iran up to the present time.

- Top American strategic thinker Edward Luttwak argues the plans being put to US President Obama for an elaborate and lengthy military strike on Iran ignore better and safer military options.

- US and German military experts offer differing views of the Israeli capacity to militarily cripple Iran’s nuclear infra-structure.

- Noted Israeli counter-terrorism expert Boaz Ganor comments on the latest attacks on Israel embassies, presumed to be by Iran or its proxies. The Jerusalem Post also had some comments in an editorial.

- Israel finds an Iranian-made explosive device being used in Gaza.

- A report Iran is significantly increasing troop numbers in Syria. (A Chinese newspaper reported it was 15,000 Iranian special forces.) Plus, Iranian ships are reportedly disrupting Syrian opposition communications.

- Veteran Australian Jewish leader Isi Leibler comments on the latest book and claims by controversial American Jewish journalist Peter Beinart.

- Given the furore about hunger striking Palestinian detainee Khader Adnan (who has just agreed to stop his hunger strike), some facts about the man and his links to Islamic Jihad.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- A Fisking of the ABC “Four Corner’s” use of wild polemicist Robert Fisk as its “expert” on Syria.

- A good discussion of India’s reaction to the bombing of the Israeli Embassy in Dehli, as well as the related issue of sanctions against Iran.

- The African Union helps Sudan’s President escape genocide charges.

Why Iran thinks it needs the bomb

By Ray Takeyh

Washington Post,

Bombastic claims of nuclear achievement, threats to close critical international waterways, alleged terrorist plots and hints of diplomatic outreach — all are emanating from Tehran right now. This past week, confrontation between Iran and the West reached new heights as Israel accused Iran of a bombing attempt in Bangkok and others targeting Israeli diplomats in India and Georgia. And yet, on Wednesday, an Iranian nuclear negotiator signaled that Tehran wants to get back to the table.

What does Iran really want? What, as strategists might ask, are the sources of Iranian conduct?

The key to unraveling the Islamic republic lies in understanding Iran’s perception of itself. More than any other Middle Eastern nation, Iran has always imagined itself as the natural hegemon of its neighborhood. As the Persian empire shrank over the centuries and Persian culture faded with the arrival of more alluring Western mores, Iran’s exaggerated view of itself remained largely intact. By dint of history, Iranians believe that their nation deserves regional preeminence.

However, Iran’s foreign policy is also built on the foundations of the theocratic regime and the 1979 revolution. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini bequeathed to his successors an ideology that divided the world between oppressors and the oppressed. The Islamic revolution was a battle for emancipation from the cultural and political tentacles of the iniquitous West. However, Iran was not merely seeking independence and autonomy, but wanted to project its Islamist message beyond its borders. Khomeini’s ideology and Iran’s nationalist aspirations created a revolutionary, populist approach to the region’s status quo.

Iran’s enduring revolutionary zeal may seem puzzling because, in many ways, China has come to define our impressions of a revolutionary state. At the outset, ideology determined Beijing’s foreign policy, even to the detriment of its practical interests, but over time, new generations of leaders discarded such a rigid approach. Today, there is nothing particularly communist about the Chinese Communist Party.

By the 1990s, Iran appeared to be following in the footsteps of states such as China and Vietnam, as pragmatic leaders such as Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and reformers such as Mohammad Khatami struggled to emancipate their republic from Khomeini’s onerous ideology. But what makes Iran peculiar is that this evolution was deliberately halted by a younger generation of leaders such as Mahmoud Ahmadinejad who rejected the pragmatic approach in favor of reclaiming the legacy of Khomeini. “Returning to the roots of the revolution” became their mantra.

Under the auspices of an austere and dogmatic supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, a “war generation” is taking control in Iran — young rightists who were molded by the prolonged war with Iraq in the 1980s. Although committed to the religious pedigree of the state, the callow reactionaries have at times been critical of their elders for their passivity in the imposition of Islamic cultural restrictions and for the rampant corruption that has engulfed the nation. As Iran’s revolution matures, and the politicians who were present at its creation gradually fade from the scene, a more doctrinaire generation is taking command. Situated in the security services, the Revolutionary Guard Corps and increasingly the elected institutions, they are becoming more powerful than their moderate elders.

This group’s international outlook was shaped by the devastating Iran-Iraq war. In the veterans’ self-serving view, Iran’s failure to overthrow Saddam Hussein had more to do with superpower intervention and less to do with their poor planning and lack of resources. The Western states and the United Nations, which failed to register even a perfunctory protest against Iraq’s massive use of chemical weapons, are to be treated with suspicion and hostility. Struggle and sacrifice have come to displace dialogue and detente.

As with Khomeini, a central tenet of the young conservatives’ foreign policy perspective is that Iran’s revolution was a remarkable historical achievement that the United States can neither accept nor accommodate. The Western powers will always conspire against an Islamic state that they cannot control. The only way Iran can be independent and achieve its national objectives is through confrontation. The viability of the Islamic republic cannot be negotiated with the West; it has to be claimed through steadfastness and defiance.

Iran’s nuclear program did not begin with the rise of this war generation. The nation has long invested in its atomic infrastructure. However, more so than any of their predecessors, Iran’s current rulers see nuclear arms as central to their national ambitions. While the Rafsanjani and Khatami administrations looked at nuclear weapons as tools of deterrence, for the conservatives they are a critical means of solidifying Iran’s preeminence in the region. A hegemonic Iran requires a robust and extensive nuclear apparatus.

The maturing of the nuclear program has generated its share of nationalistic fervor, and the regime has certainly done its share to promote the importance of the atomic industry as a pathway to scientific achievement and national greatness. >From issuing stamps commemorating the program to celebrating the enrichment of uranium, the clerical regime believes that a national commitment to nuclear self-sufficiency can revive its political fortunes.

The problem with this approach is that, once such a nationalistic narrative is created, it becomes difficult for the government to offer any concessions without risking a popular backlash. After years of proclaiming that constructing an indigenous nuclear industry is the most important issue confronting Iran since the nationalization of the oil industry in 1951, the government will find it difficult to justify compromises. The Islamic republic’s strategy of marrying its identity to nuclear aggrandizement makes the task of diplomacy even more daunting.

Yet, Iran’s determination to advance its nuclear program has come at a considerable cost. Today, the country stands politically and economically isolated. The intense international pressure on Iran has seemingly invited an interest in diplomacy.

From Tehran’s perspective, protracted diplomacy has the advantage of potentially dividing the international community, shielding Iran’s facilities from military retribution and easing economic sanctions. Iran may have to be patient in its quest to get the bomb; it may have to offer confidence-building measures and placate its allies in Beijing and Moscow. Any concessions it makes will probably be reversible and symbolic so as not to derail the overall trajectory of the nuclear program.

Can Tehran be pressed into conceding to a viable arms-control treaty? On the surface, it is hard to see how Iran’s leaders could easily reconsider their national interest. The international community is confronting an Islamic republic in which moderate voices have been excised from power.

However, it may still be possible to disarm Iran without using force. The key figure remains Khamenei, who maintains the authority and stature to impose a decision on his reluctant disciples. A coercive strategy that exploits not just Khamenei’s economic distress but his political vulnerabilities may cause him to reach beyond his narrow circle, broaden his coalition and inject a measure of pragmatism into his state’s deliberations. As with most ideologues, Iran’s supreme leader worries more about political dissent than economic privation. Such a strategy requires not additional sanctions but considerable imagination.

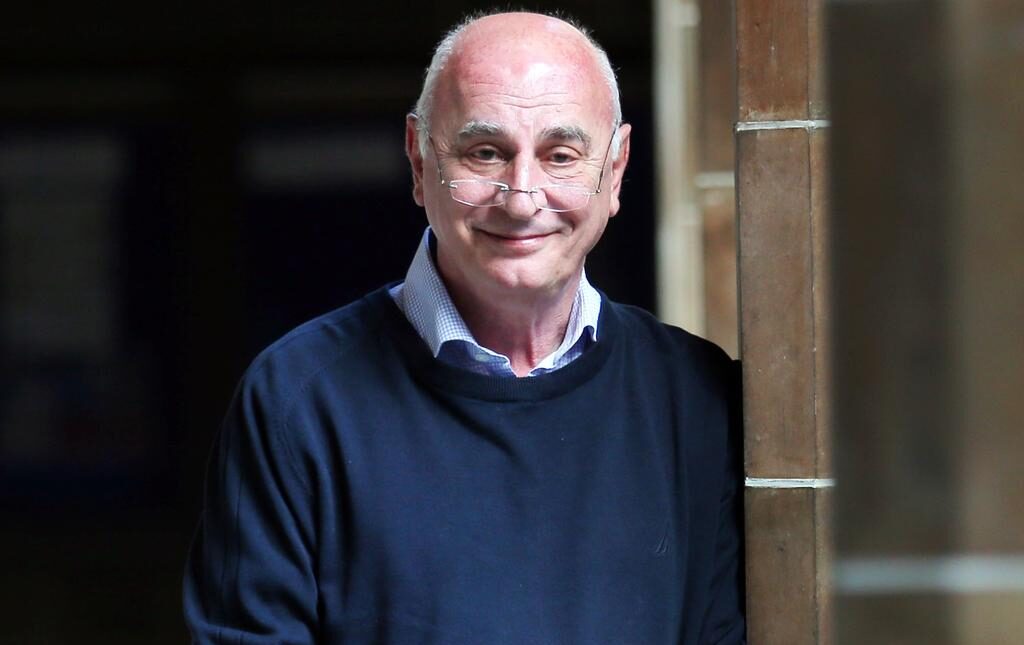

Ray Takeyh is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of “Guardians of the Revolution: Iran and the World in the Age of the Ayatollahs.”

Back to Top

————————————————————————

How Iran sees America and what America does not want to see

FoxNews.com, Published February 17, 2012

President Obama entered the White House determined to renew diplomacy with Iran. During his campaign, he said he would meet the leaders of Iran “without preconditions.”

In his inaugural address he said, “To those who cling to power through corruption and deceit and the silencing of dissent, know that you are on the wrong side of history, but that we will extend a hand if you are willing to unclench your fist.”

Obama was sincere, but his outreach was doomed before it began. The problem was never American goodwill but rather how Iran’s leaders understand diplomacy.

American diplomacy is based on the assumption that international counterparts operate by common rules.

The Western notion of diplomacy, however, is a relatively recent concept, one that evolved during the Enlightenment and coalesced into a common understanding only in the nineteenth century.

To assume that twenty-first century adversaries, be they in Tehran, Pyongyang, or Beijing, accept a value system rooted in Western culture is naive.

The match-up between Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and Obama is not a battle between equals, but rather a historical grudge match between Nizam al-Mulk, the eleventh century Persian Machiavelli, and Neville Chamberlain or Jimmy Carter.

In that game, the White House will always lose, especially when if it refuses to recognize the rules by which Iran plays.

The cultural chasm between American and Iranian diplomats predates the 1979 hostage crisis.

Less than three months before radical students seized the U.S. embassy, Bruce Laingen, the American chargé d’affaires in Tehran, described the Iranian approach to negotiations to the State Department. “Perhaps the single dominant aspect of the Persian psyche is an overriding egoism,” he wrote in a cable, adding, “The practical effect of it is an almost total Persian preoccupation with self and leaves little room for understanding points of view other than one’s own.” “One should never assume that his side of the issue will be recognized,” he concluded.

That, after 32 years, no Iranian official has apologized for seizing the U.S. embassy underscores Laingen’s insight and shows the Iranian regime’s complete rejection of the rules of diplomacy. Iranians have grievances too—the 1953 coup against Iran’s Soviet-leaning premier, for example—but for this successive administrations have apologized.

The Islamic Republic’s embrace of terrorism also underscores the cultural gap. Tehran refuses the terrorist label, only because it believes wanton murder of civilians acceptable. Export of revolution is enshrined in the Islamic Republic’s constitution and the Iranian government has been so bold as to include a line-item for “resistance” in its budget.

During the last administration, critics chastised the President Bush for eschewing realism, the idea that immediate national interest should trump morality in decision making. Obama may believe he embraced realism, but he fails to recognize it in his adversaries: Iranian authorities make no secret that their primary national interest lays in becoming a nuclear power.

Here, again, American strategy is naïve: Obama may, like Bill Clinton before him, believe that he can exploit Iranian factional disputes to his advantage but he ignores that reformists and hardliners both seek a nuclear Iran. Indeed, the biggest dispute between the two poles on the Iranian political spectrum is not whether or not to go nuclear, but rather who should get credit for the achievement.

When Ahmadinejad announces nuclear breakthroughs, as he did on Wednesday, he seeks glory for himself, but reformists say they deserve credit.

In June 2008, for example, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh, the spokesman for former president Mohammad Khatami, suggested Khatami’s much-lauded “Dialogue of Civilizations” was merely a tactic to distract the West from Iran’s nuclear progress. Former nuclear negotiator Hassan Rowhani seconded the notion in October 2011, crediting his own insincere diplomacy for enabling Iran to create a nuclear fait accompli.

While many American officials still cling to the 2007 National Intelligence Estimate’s controversial assertion that Iran ceased working on a nuclear weapon in 2003, they ignore the fact that it was during the reformist era that Iran laid the backbone of its program.

Absent sincerity, diplomacy is less a system for problem solving than it is an asymmetric warfare strategy.

Only twice has the Islamic Republic reversed course on its revolutionary goals: First, Ayatollah Khomeini released American hostages, not because of Carter’s diplomacy but rather because Iraq’s 1980 invasion made the price of Iran’s isolation too great to bear.

Then, only after a half million Iranians died, did Khomeini agreed to abandon the Iran-Iraq war short of his goal of ousting Saddam Hussein, likening the decision to drinking a chalice of poison.

Iranians often quip that they play chess while the Americans play checkers. They are wrong. By ignoring the Iranian game, Obama might as well be playing solitaire.

Tehran will feign pragmatism only when the cost of its goals—nuclear acquisition and revolutionary expansion—grow too costly. Only by raising exponentially the cost to Iran of its nuclear defiance can Obama hope to rein in Iranian ambitions.

Michael Rubin, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, teaches Iranian history and political culture for the U.S. military and holds a Ph.D. in Iranian history from Yale University.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

How the U.S.-Iran Standoff Looks From Israel: Efraim Inbar

Bloomberg, Feb 19, 2012

The upheaval in the Arab world has damaged Israel’s strategic environment. Its peace treaty with Egypt, a pillar of national security for more than three decades, is in question. More important, the events in the Arab world have deflected attention from Israel’s most feared scenario, a nuclear Iran, playing into the Iranian strategy to buy time in order to present the world with a nuclear fait accompli. Israel’s leaders fear that the international response is now unlikely to impact Iranian policy, at a point when its nuclear program is so advanced.

Only in November 2011 did the International Atomic Energy Agency, an institution that for years refused to call a spade a spade, publish a report voicing its concern over Iranian activities that do not easily fit with those of a civilian program. And only in January, did the European Union and the U.S. declare new sanctions that could have a significant effect on Iran’s economy. For Israel, this may have come too late.

Officials in Tel Aviv have tried to alert the West to the dangers of a nuclear Iran for more than a decade. They argued that Iran would cause the technology to proliferate in the region as states such as Turkey, Egypt and Saudi Arabia sought such weapons, turning a multipolar nuclear Middle East into a strategic nightmare. A nuclear-armed Iran would strengthen its hegemony in the energy sector by its mere location along the oil-rich Persian Gulf and the Caspian Basin.

It would also result in the West’s loss of the Central Asian states, which would either gravitate toward Iran or try to secure a nuclear umbrella with Russia or China, countries much closer to the region than the U.S. is. A regime in Tehran emboldened by the possession of nuclear weapons would become more active in supporting radical Shiite elements in Iraq and agitating those communities in the Persian Gulf states.

Bombs to Proxies

Worse, since Iran backs terrorist organizations such as Hezbollah, Hamas and Islamic Jihad, it may be reckless enough to transfer nuclear bombs to such proxy organizations. They would have no moral constraints on detonating such a device in a European or American harbor. Iran’s nuclear program — coupled with further improvements in Iranian missiles — would initially put most European capitals, and eventually North American ones, within range of a potential attack.

Such arguments are nowadays more acceptable, but a large part of the Western strategic community, particularly on the European side of the Atlantic, views Iran as a rational actor that still can be dissuaded by economic sanctions. Moreover, even if Iran gets the bomb, it is argued that “it can be contained and deterred,” rejecting the “alarmist” view from officials in Jerusalem.

Israel is increasingly exasperated with Western attitudes for several reasons. First, it doesn’t believe that when Iran is so close to the bomb, sanctions are useful. Indeed, the history of economic sanctions indicates that a determined regime is unlikely to be affected by such difficulties. Moreover, the stakes that Iran’s ruling elite have in the nuclear program are inextricably connected to the regime’s political, and even physical, survival. The bomb is a guarantee for the government’s own future. Destabilizing a nuclear state, which may lead to chronic domestic instability, civil war or disintegration, is a more risky enterprise than undermining a non-nuclear regime.

Weak U.S. President

Unfortunately, American statements that all options are on the table, hinting at military action if sanctions fail, don’t impress the Iranians. The perception of most Middle Easterners, be it foes or friends of the U.S., is that President Barack Obama is extremely weak, hardly understands the harsh realities of the Middle East, and that American use of force is highly unlikely. Perceived American weakness undermines the chances of economic sanctions being effective.

Second, Israel’s threat perception is much higher than in the West, particularly after the recent Middle East turmoil. Actually, all Middle East leaders wear realpolitik lenses for viewing international affairs and tend to think in terms of worst-case scenarios. Israel’s leadership, in addition, sees through a Jewish prism and is unlikely to take a nonchalant view of existential threats to the Jewish state. Israeli fears have been fed by explicit statements from Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who advocated the destruction of Israel. Jewish history taught Israel that genocidal threats shouldn’t be dismissed.

Third, the strategic community in Israel questions the possibility of establishing a stable deterrence between Israel and Iran, modeled on the relationship between the two superpowers during the Cold War. Mutual deterrence between two nuclear protagonists is never automatic. Maintaining a second- strike capability is an ongoing process, which is inherently uncertain and ambiguous. Moreover, before an initial “effective” second-strike capability is achieved, a nuclear race may create the fear of a first-strike attack, which might itself trigger a nuclear exchange.

In a multipolar environment, achieving stable deterrence would be even more difficult. Middle Eastern powers would also have to establish early-warning systems that monitor in all directions. These are complicated and therefore inherently unstable, particularly when the distances between enemies are so small. The influence of haste and the need to respond quickly can have dangerous consequences. The rudimentary nuclear forces in the region also may be prone to accidents and mistakes.

While it can be argued that Middle East leaders behave rationally, many of them engage in brinkmanship leading to miscalculation. More important still, the value they place on human life is lower than in the West, making them insensitive to the costs of attack. Iranian leaders have said they are ready to pay a heavy price for the destruction of Israel, anticipating only minimal damage in the Muslim world.

As a result, the strategic calculus in Jerusalem indicates that preventing a nuclear Iran is important and urgent, justifying risks and considerable costs. Delaying Iran’s nuclear ambitions by even a few years would be a worthwhile achievement. Moreover, the feeling in Israel is that the fears many analysts express of regional repercussions from an Israeli military strike are exaggerated.

The debate in Jerusalem is whether to allow more time for covert operations, or to initiate a pre-emptive strike against Iran’s nuclear installations. This is not an easy decision to make. An unexpectedly muscular Western move may spare Israel’s government the deliberations, but there is little hope that such a scenario will materialize. Once again, the Israelis would be left to go it alone.

(Efraim Inbar is a professor of political studies at Bar- Ilan University and the director of the Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies. This is the fourth in a series of op-ed articles about Iran, from writers in countries that have a direct interest in the escalating debate over how to rein in its alleged nuclear weapons program. The opinions expressed are his own.)

Tags: International Security