UPDATES

Hezbollah and the Syrian Civil War

May 31, 2013

Update from AIJAC

May 31, 2013

Number 05/13 #06

This Update deals with the aftermath of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s very public announcement last week that Hezbollah was essentially completely dedicated to fighting “all out” on the side of the Assad regime in the Syrian civil war, following widespread reports that large numbers of Hezbollah fighters have been involved in the extended battle for the strategic Syrian town of Qusayr – plus what this means for Syria, Lebanon and the region.

The first comment comes from Dexter Filkins of the New Yorker who warns that Hezbollah’s open entry to the Syrian war is a “terrifying development”, risking regional war. He is particularly concerned that this move makes the Syrian War very likely to spread to Lebanon – and sees signs this is already happening, with a rocket attack on Hezbollah-dominated neighbourhoods of Beirut. He also notes that Lebanese Sunnis are also fighting on the opposite side of the Syrian Civil war, and implies it may now be too late to stop the likely spread of the conflict with a change of Western policy. For his complete argument, CLICK HERE.

Next up is Washington Institute military expert Jeffrey White, looking at the tactical and strategic implications of Hezbollah’s decision to go “all-in” in Syria. Among these are a a shift in the balance of forces in Syria, a likely weakening of Hezbollah’s position in Lebanon, and some advantages for Israel, with Hezbollah likely weakened by the losses being take in Syria. However, most importantly, he warns that the shift in the balance of forces in Syria, thanks to Hezbollah’s intervention, may be decisive, meaning the regime could well win the war – unless the rebels are given more help to upgrade their capabilities. For this sober look at the military realities in Syria and beyond, CLICK HERE.

Finally, author and analyst Lee Smith offers a different assessment, emphasising the damage – both physical and in terms of Lebanese and regional opinion – being done to Hezbollah and the organisation’s lack of attractive options. He emphasises that Hezbollah is clearly acting directly as an Iranian proxy in Syria and the whole conflict there can now be seen as simply “rebels vs. a large Iranian-trained and supplied force”. He sees in the situation in Syria increasing signs that the whole Iranian regional strategy of exporting its revolution by emphasising “Islamic resistance” so as “to jump the Sunni-Shia divide, as well as the Arab-Persian one” appears to be collapsing. For the rest of Smith’s analysis, CLICK HERE. Agreeing that Hezbollah’s situation in Syria is looking like a quagmire are Lebanese writers Tony Badran and Michael Young.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Noted Middle East academic Prof. Fouad Ajami – himself of Lebanese Shi’ite ancestry – discusses what Hezbollah really is.

- More on the state of the Syria civil war and the problems and imperatives for Israel here and here . Plus a comment on Nasrallah’s announcement and its implications for Israel from the Jerusalem Post.

- Elliot Abrams writes about Iran’s “Brezhnev Doctrine” (the Soviet doctrine which said no one is allowed to leave the Communist bloc) in Syria, and separately, how the Hezbollah actions fit into this picture.

- Plus, Michael Weiss argues there is little reason to expect Russia’s pro-Assad policy to change. Meanwhile, hopes of a planned peace conference on Syria will go ahead or be productive it it does seem to be dwindling.

- Harvard’s Chuck Freilich suggests some ways that Washington can make its “red line” on Syrian chemical weapons use meaningful.

- Isi Leibler writes about rising global antisemitism.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Allon Lee, in his “Media Week” column, takes on a particularly ugly and ill-informed peace on the Middle East impasse from British academic Lori Allen on “the Conversation.” Plus, Or Avi-Guy dissected Allen’s claim that the impasse is ” all because of settlements.”

- Daniel Meyerowitz-Katz responds to some Greens politicians who have attacked the London Declaration on Combating Antisemitism for supposedly making “criticism of Israel” antisemitic.

- Ahron Shapiro had an op/ed in Online Opinion on the same theme.

- Sharyn Mittelman on what Israeli technology is doing for India.

Hezbollah Widens the Syrian War

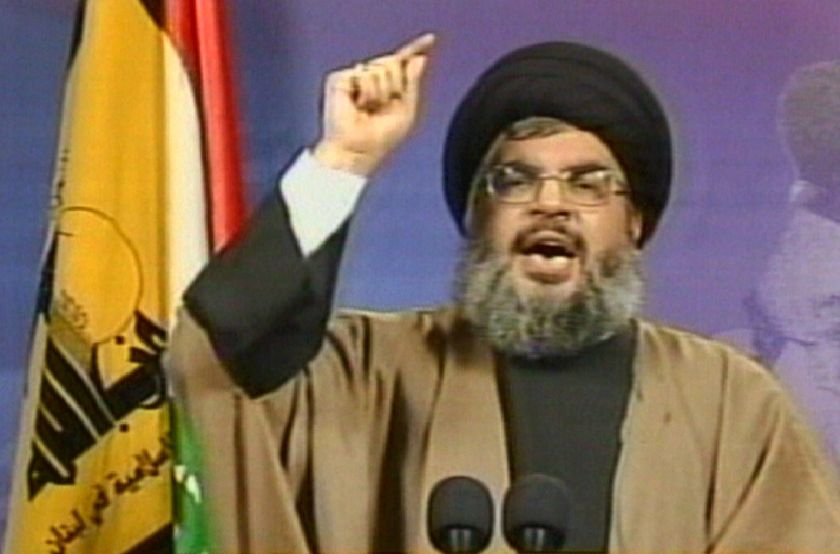

It’s official: the war in Syria has spread to Lebanon. In an extraordinary speech Saturday, Hassan Nasrallah, the bearded and bespectacled leader of the Lebanese militant group, Hezbollah, promised an all-out effort to keep the murderous regime of Bashar al-Assad in power in Syria. “It’s our battle, and we are up to it,” Nasrallah said in a televised address. The war, he said, had entered “a completely new phase.”

This is a terrifying development; the beginning of a regional war. Hezbollah, the Iranian-backed armed group, has been fighting inside Syria for months, something I detailed in an article on the group in February. But Hezbollah was intervening in Syria covertly, in large part because it feared a backlash at home. Month after month, Nasrallah denied that his men were fighting for the dictator across the border. When Hezbollah fighters were killed in Syria, they were memorialized in bizarre funerals back in Lebanon, in which the causes of death were not mentioned. In public, Nasrallah maintained that Hezbollah was the same thing it always had been: an armed group dedicated to protecting Lebanon from the depredations of Israel. In a speech in October, he said: “As of now, we have not fought alongside the regime.” As more and more Hezbollah fighters died inside Syria, that lie could no longer be sustained. The truth is out.

On Saturday, by declaring his undying loyalty to the Assad regime, Nasrallah has signalled an escalation in Hezbollah’s involvement. Nasrallah is now personally committed to the survival of Assad’s regime, no matter how murderous it becomes. His logic involves naked self-interest: Syria provides Hezbollah with its crucial link to the regime in Iran, Hezbollah’s creator and benefactor. Without Assad, Hezbollah might not be able to survive.

It’s difficult to overstate how dangerous this new phase is. At the moment, the conflict in Syria is a war of attrition, essentially a contest between the country’s Sunni Muslim majority and its Alawite-dominated government and military. Each side is doing its best to butcher the other, but neither appears to be prevailing. A massive intervention by Hezbollah would obviously be aimed at tipping the balance in Assad’s favor. Indeed, it was no coincidence that Nasrallah decided to give his speech during a big battle for the Syrian city of Qusayr, where Hezbollah appears to have suffered heavy losses. Qusayr lies on the road between Damascus and the Syrian cities on the Mediterranean coast, the stronghold of the Alawites, the minority sect that is loyal to Assad. For obvious reasons, the Assad regime in Damascus wants to hold the highway to the coast. It’s unclear how much a difference a new infusion of Hezbollah fighters will make, but it can’t hurt.

But the most serious effects of Hezbollah’s stepped-up intervention in the Syrian war will be felt in Lebanon itself. Lebanon—which, like Syria, was created from the ruins of the Ottoman Empire in the years after the First World War—had its own civil war, which lasted from 1975 until 1990. (That’s fifteen years.) Since then, the peace in Lebanon has depended on a delicate balance among the country’s main sects: the Sunnis, Shiites, and Christians. To a great extent, this peace has depended on each group refraining from trying to grab too much power at the expense of the others. Over the past several years, Nasrallah has pushed this arrangement to the limit; Hezbollah is not just a political party but an army that is more powerful than the Lebanese state. Inside Lebanon, it its unassailable. Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria—essentially, a Shiite army crossing the border to kill Sunnis—represents a flagrant violation of Lebanon’s fragile sectarian pact.

Brace yourself for the consequences. On Sunday, Hezbollah’s headquarters in southern Beirut was nearly struck by two rockets fired by unidentified fighters—the first time in years that the group has come under attack there. Last week, sectarian fighting broke out between Sunnis and Alawites in the northern city of Tripoli—not a new thing, but the bloodiest in a long time.

Hezbollah isn’t the only group that has been intervening in the Syrian civil war. Since the Syrian conflict began, Lebanese Sunnis have been slipping across the border to support the rebels, but in a mostly unorganized, haphazard way. The Syrian rebels themselves have promised to avenge Hezbollah’s activities by taking the fight into Lebanon. The most dramatic example of the Syrian civil war’s effect on Lebanese politics came in March, when Prime Minister Najib Mikati resigned. Mikati, a Sunni, was in a coalition with Hezbollah. It doesn’t take much to see how difficult it is in Lebanon today for a Sunni politician to work with Hezbollah, whose fighters are killing Sunnis across the border.

What comes next? So far, the peace in Lebanon has mostly held, in no small way because memories of the civil war there are still fresh. But as Hezbollah commits itself more deeply to the Syrian war, the more difficult it will be to contain the violence in Lebanon itself. It’s not difficult to imagine Lebanon slipping into a new civil war of its own.

Since the Syrian revolt began more than two years ago, President Obama has stayed mostly out, even as Assad’s regime has become more indiscriminate in its use of violence. (The United States has provided non-lethal aid to the rebels, but has not intervened militarily.) In essence, the President has reasoned that the war in Syria is too complicated for the United States to have much influence.

Perhaps Obama is right. But it’s also true that the White House’s reluctance to act has allowed the war in Syria to run off on its own horrendous course. And now, as Hezbollah escalates inside Syria, it might be too late to stop the war from spreading beyond its borders.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Hezbollah’s Declaration of War in Syria: Military Implications

Jeffrey White

PolicyWatch 2080, May 29, 2013

Hezbollah’s commitment to the Syrian conflict will likely change the course of the war.

On May 25, Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah made what amounts to a declaration of war against the Syrian revolution. He committed his group to defeating the rebellion and preserving the regime of Bashar al-Assad, declaring that “Syria is the resistance’s main supporter, and the resistance cannot stand still and let takfiris [extremist Sunnis] break its backbone.” No one can fault him for lack of clarity; this was not a speech cloaked in ambiguity. Assuming he follows through on his commitment to protect Assad’s regime, both the speech and Hezbollah actions already underway in Syria could profoundly affect the war’s military course, the security situation in Lebanon, and the group’s military contest with Israel.

DIRECT AND INDIRECT INTERVENTION

Hezbollah’s involvement in the current fighting around al-Qusayr in Homs province is its most salient action in Syria to date, but that is only part of the picture. The group has been engaged in direct military intervention in Damascus for some time, purportedly to defend the Sayyeda Zainab Shiite shrine in cooperation with local Shiite militiamen of the Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas Brigade. And according to rebel sources, Hezbollah members have joined regime offensives in Deraa province as well as East Ghouta in the Damascus countryside — areas where the government is showing renewed offensive capabilities.

Hezbollah has also played a key role in the regime’s development of effective irregular forces. It reportedly provides training and advice to local militia groups, Popular Committee elements, and the National Defense Army, all of which are playing a growing role in the regime’s defense.

To be sure, Hezbollah’s forces, even elite units, are not supermen — even when backed with regime air, armor, artillery, and missile forces, their performance against the Syrian rebels has been less than spectacular. Hezbollah elements fighting around al-Qusayr have paid a heavy price, making slow progress on the ground but failing to dominate rebel forces. The battle for al-Qusayr city has been underway for ten days, and the group’s operations in the surrounding area have been underway for at least seven weeks. This is no blitzkrieg, and it is costing Hezbollah numerous casualties, including commanders and fighters from its best units. Nevertheless, the group’s efforts have shifted the local balance of forces in the area. In combination with regular and irregular regime elements, Hezbollah’s contribution will likely lead to an eventual rebel defeat there; the regime cannot lose this battle, and it will commit the forces necessary to win it.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SYRIA

Hezbollah’s all-in commitment is perhaps the single most important development of the war thus far and will profoundly affect its course. Direct and significant military intervention by Hezbollah gives the regime new capabilities and restores its ability to conduct significant offensive operations. In al-Qusayr, for example, the regime can use the group’s fighters as a reliable infantry force alongside its own heavy weapons and airpower. Hezbollah forces have the training and experience to conduct attacks with skill and determination, and at least so far, they have demonstrated the willingness to accept the casualties necessary to achieve their objectives — something lacking to a degree in regime forces. Their involvement also gives the regime dependable infantry for the defense of key areas.

In addition, Hezbollah intervention reduces the burden on regime forces strained by more than two years of war. Over time, this could allow Assad to rest and redeploy some of his forces for operations elsewhere in Syria, including efforts to retake certain rebel-held areas.

Perhaps most important, Hezbollah’s decision may deny the rebels a chance for overall victory. Already facing the major challenge of overcoming regime forces, the armed opposition now faces the prospect of having to defeat Hezbollah forces as well, which could be a bridge too far.

IMPLICATIONS FOR LEBANON

Nasrallah has shown once again that when the chips are down, Hezbollah will place its own interests above Lebanon’s. His latest commitment has put the country’s stability and the fate of his organization at risk. The Syrian war was already leaking into Lebanon before his speech, largely due to Hezbollah’s increasing cross-border involvement. This led to rebel artillery strikes inside Lebanon, the mobilization of Lebanese Sunni fighters for combat in al-Qusayr, and Sunni-Shiite clashes inside Lebanon. Such problems will likely get worse in the wake of Nasrallah’s declaration.

Hezbollah’s Syria campaign is also exposing some longstanding illusions about the group in Lebanon and abroad. First, the group’s image as the leader of the “resistance” against Israel is taking a hit. Although Nasrallah attempted to paint his decision as part of the wider struggle against Israel and the United States, the clear effect of Hezbollah actions is to kill Sunnis resisting their own government. Second, the Lebanese Armed Forces have been exposed as essentially the protectors of Hezbollah’s rear areas, expected to keep the roads open while the group moves fighters into Syria at will. Third, the fighting around al-Qusayr is damaging Hezbollah’s carefully maintained myth of invincibility. While its media arms speak of victories in Syria, the frequent funerals for Hezbollah members back home are difficult to ignore. The group’s friends and foes in Lebanon will be watching its performance in Syria and the cost of its role there.

IMPLICATIONS FOR ISRAEL

For Israel, Hezbollah’s turn to Syria could have some positive consequences. As described above, the group is already taking significant casualties, with tens killed in action and many more wounded. As its involvement deepens, many more casualties could ensue, including among senior commanders and experienced personnel. This will weaken Hezbollah, at least in the short term.

Nasrallah’s decision will also distract Hezbollah from the contest with Israel. As the group’s forces and resources are drawn into the Syria fight, its ability and willingness to confront Israel will be reduced. Hezbollah is in no position to fight a two-front war.

BROADER IMPLICATIONS

Hezbollah’s public entry into the war adds yet another log to the fire — the gradual expansion of combatants in Syria now includes fighters from several countries and factions. Iraqi militants have joined both sides, with some bolstering the rebels and others reportedly playing a key role in certain regime operations. Sunnis from Lebanon are fighting the regime in al-Qusayr, and rebel sources have reported the presence of Iranian combat elements in several battles despite denials from Tehran. Indeed, the war is creating a free market” for external state and nonstate actors with an interest in the outcome and the necessary resources, and these new entrants will only energize the conflict.

Hezbollah’s commitment in particular will change the equation on whatever battlefields the group fights, giving the regime renewed offensive and defensive capabilities and greater resources. It will also boost morale among the regime’s forces and supporters, encouraging Assad to stay the course and crush the rebellion. As a result, the regime will be even less likely to negotiate a true transition of power, deflating the hopes of those pressing for a diplomatic solution. A regime that has shown no inclination to negotiate while losing the war will hardly be moved to compromise if it believes its prospects have improved.

Hezbollah’s bold action stands in sharp contrast to the feeble response from supporters of the Syrian opposition. Without a significant upgrading of rebel capabilities — either from their own resources, outside assistance, or both — Nasrallah’s declaration could prove decisive to the war’s outcome.

Jeffrey White is a defense fellow at The Washington Institute and a former senior defense intelligence officer.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Hezbollah’s Heavy Losses

After a week’s worth of fighting in Syria, the Islamic resistance licks its wounds.

For over a week now, the Syrian town of Qusayr in Homs Province has seen some of the heaviest fighting in the two-year conflict. The struggle for Qusayr, says besieged President Bashar al-Assad, “is the main battle” in all of Syria. Lying adjacent to a highway linking Homs to the north and Damascus to the south, Qusayr is only a few miles from the Lebanese border and is thus a strategically vital node for both the regime and the rebels.

For the rebels, it’s part of a western supply route linked to Tripoli in northern Lebanon, where the rebels have enjoyed support since the uprising began in March 2011. For the Assad regime, Qusayr links Hezbollah strongholds in Lebanon to the Alawite homeland on the Mediterranean coast, where Assad and his supporters will likely seek safe haven should they lose Damascus. In order to retake Qusayr from the rebels who have held it almost a year, the regime has ordered air strikes and called in reinforcements from Hezbollah as well as Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps forces.

Earlier reports suggested that Assad and allies had pushed the rebels out, but opposition activists say this is regime propaganda. “It’s not true what the regime is claiming,” said one Qusayr-based activist. “They’re saying this to raise the morale of the fighters, because the rebels are giving them a beating.” Indeed, Hezbollah itself seems to be absorbing heavy casualties, with 46 reportedly killed in Qusayr over the last week. Other sources claim that given the number of funerals in southern Lebanon and other Hezbollah-controlled regions over the last few days, the death toll may be closer to 100.

As Tony Badran, a fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, writes in NOW Lebanon, “If the casualty rate stays this high even for another week, it could prove devastating.” Badran explains that many of those killed in the first day of fighting were ambushed during the initial assault and “cut down by landmines and IED’s prepared by the Syrian rebels.” The rebels, writes Badran, “received assistance from certain Palestinian factions in planning the defense of the town.” Unconfirmed reports suggest that those Palestinian factions may include Hamas. In other words, two militias trained and armed by Iran—one Sunni, one Shia—may now be shooting at each other, with the side that the Islamic Republic has invested in most heavily losing.

At this point, it’s perhaps most accurate to describe the war not in terms of the Sunni-majority opposition vs. Assad, but the rebels vs. a large Iranian-trained and supplied force, including Assad’s military, his paramilitary gangs, Hezbollah, IRGC units, the popular militias, as well as Iranian-backed organizations from Iraq, like Asaib ahl al-Haq and Kitaeb Hezbollah. As Elliott Abrams writes in this week’s issue, the supreme leader “wants to win and he understands that whether he wins or loses is immensely important.” Indeed, given the amount of resources Tehran has now poured into winning Syria, it’s no longer Assad’s regime, but Iran’s. If Assad was once Iran’s junior partner, he’s now simply an Iranian protégé, and not necessarily the most important one fighting in Syria. That would probably be Hezbollah, which is why Qusayr is a key battlefield. Even if Assad doesn’t survive, key remnants of the regime will, and therefore holding that corridor between the Alawite coastal region and Hezbollah-held areas of Lebanon is a vital Iranian interest. What matters to Iran is not Assad, but the territory.

As Badran explains, it was Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei and Qods Force commander Qassem Soleimani who ordered Hezbollah general secretary Hassan Nasrallah to send fighters to defend Iran’s vital interests in Syria. However, Hezbollah’s performance to date suggests that the Iranians may be holding a much weaker hand than they let on. If the Party of God is trounced by the Syrian rebels, what does that say of Hezbollah’s ability to make war on Israel?

One issue of course is that Hezbollah is not accustomed to this kind of combat. Typically the party of God fights guerilla wars on its own terrain, where it not only knows every inch of the territory, but is also able to melt into the civilian population whose support it can count on. With Qusayr, Hezbollah finds itself on unfamiliar ground and having trouble mounting an offensive, as this sound recording of Hezbollah fighters at Qusayr in apparent disarray shows.

Hezbollah has come under heavy criticism throughout the Middle East, especially in Lebanon and even its own Shia community, for making war on Syrians and thereby showing that the banner of resistance against Israel was merely a ruse. With Qusayr, Hezbollah has dropped all pretense of “resistance” and is instead an occupying force—and one subject to the same sorts of tactics, including ambushes, it normally employs against Israel. Hezbollah’s failures as an expeditionary force are a significant problem, as Badran explains, because the organization has let on that in the next round with the IDF it will go on the offensive and infiltrate northern Israel. Qusayr may well give Iran second thoughts about taking the fight to the enemy.

Indeed, Tehran may need to reconsider its regional strategy in its entirety. How much of an asset is Hezbollah in protecting Iran’s nuclear program? If the United States or Israel were to strike its nuclear facilities now, it’s doubtful Hezbollah would be able to fight on two fronts at once. The other issue is the quality and number of Hezbollah fighters. The July 2006 war with Israel cost Hezbollah between 500-600 dead, Badran writes, leaving them with a depleted force of experienced fighters. Pictures of the Hezbollah members killed in Qusayr show that most of the dead are too young to have been of fighting age in 2006. Rather, they’re recruits, “elite” by Hezbollah standards, but effectively cannon fodder. Sources explain that families of the dead are starting to grumble, wondering why their boys are being sent off to die in Syria. After all, if the purpose of Hezbollah is to defend Lebanon from Israel, wouldn’t sending fighters to Syria make the home-front more vulnerable to the depredations of the Zionists? That’s perhaps why Hezbollah is reluctant to send more experienced fighters to Syria—though there have already been some older members, perhaps commanders, killed—since it means risking losing battle-hardened units for the next round with Israel.

Hezbollah just doesn’t have any good options right now, unless they’re able to turn things around on the battlefield. If they don’t, Iran is in a bind. All that money and time Tehran has invested in exporting Khomeini’s revolution may come to nothing in the end. After all, the point of the Islamic resistance was to jump the Sunni-Shia divide, as well as the Arab-Persian one. As long as Iran could herd the Muslim Middle East into one big fold of resistance against Israel and the West, it could dream of overturning a millennium of Middle East history dominated by the Sunnis. That’s coming to look more and more like a millennial fantasy.