UPDATES

China makes strides in the Middle East

February 11, 2022 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

02/22 #02

This Update features reporting and analysis on some major strides China has recently made toward consolidating a much more significant role in the Middle East – first with a series of visits by Middle Eastern leaders to Beijing in January, and then with Middle Eastern nations being key among those who refused to join a US-led political boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics this month.

In addition, Beijing also showed off its ability to project power to the area via trilateral naval exercises with its allies Russia and Iran in the Persian Gulf last month.

First up is some commentary by American expert Saeed Ghasseminejad on the rash of visits to Beijing by Middle Eastern leaders. Ghasseminejad argues that the visits reflect shifts in economic relations and documents that China is now by far the biggest trading partner with nations like Saudi Arabia, while trade with the US is declining. He argues that the US policy of retreating from the Middle East and “pivoting to Asia” is having the opposite effects to those intended, allowing China to build relationships with Middle Eastern states that are strengthening and emboldening Beijing. For Ghasseminejad’s important argument in full, CLICK HERE.

Next up is a New York Times article reporting on the signs of growing Chinese relationships in the Middle East, and quoting some experts on why it is happening. Israeli academic analyst and former AIJAC staffer Gedaliah Afterman sums up the overall picture as: “There is a feeling in the region that the United States is actively on the way out, and that’s an opportunity for China.” The article also discusses the apparent complete lack of interest from Muslim leaders of Middle East nations in the plight of China’s Muslim Uyghurs, victims of an alleged ongoing genocide by Beijing. For this solid summary of the expansion of China-Mideast relations and it is happening, CLICK HERE.

Finally, Washington Institute for Near East Policy researcher Carol Silber looks specifically at Middle East states and the Beijing Winter Olympics. She notes that three key Middle Eastern leaders usually considered US allies were among the few major heads of state to attend the Olympics, providing a boost to Chinese President Xi’s agenda and prestige. She also reviews the history and trend of Middle East states participating in winter olympics to put these decisions in context, and offers some policy suggestions for Washington in dealing with these developments. For Silber’s analysis and insights into the politics of the Beijing Winter Olympics, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- The Washington Post’s comments on new agreements between China and Russia to try to effectively “make the world safe for dictatorship. “

- Mansour Abbas, head of the Islamist Raam party which is part of Israel’s current government, denying Amnesty International’s claim that there is “apartheid” in Israel.

- Elliot Kaufman of the Wall Street Journal offers an insightful explanation of why Amnesty and other groups are prepared to put themselves through bizarre legal gymnastics to attempt to put the “apartheid” label on Israel.

- International law expert Eugene Kontorovich points out one can make a much better case that the Palestinian Authority-ruled areas are apartheid than that Israel is.

- An interview with Israel’s new Ambassador to Australia Amir Maimon.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- In the Canberra Times, Colin Rubenstein made the case that Palestinian activists who have seized on the recent Amnesty International report ridiculously accusing Israel of apartheid are actually setting back hopes for Palestinian statehood.

- Meanwhile, on Sky News’ website, Ahron Shapiro looked at the perverse worldview of both Amnesty’s activist researchers and Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions activists against Israel, which leads them to make their extreme claims.

- Judy Maynard exposed Amnesty’s long history of politicised work, activist researchers, extreme and false claims, and other scandals.

- Ahron Shapiro looks at Israel’s efforts to come to grips with an uptick of West Bank violence by extremist settlers and their supporters.

Is the Future of the Persian Gulf Chinese?

by Saeed Ghasseminejad

The National Interest, Feb. 2, 2022

American proponents of abandoning the Persian Gulf often cite the need to pivot to Asia. However, Washington’s regional retreat may achieve the exact opposite of U.S. objectives, ultimately emboldening and empowering China.

Saudi and other Gulf leaders are beating a path to Beijing as their economies become more integrated with China – and less with the US (Image: Shutterstock, Yankittaphak Phoyalo)

In early January, the foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, and the Islamic Republic of Iran traveled to China in the span of a week to strengthen their ties with the Chinese Communist Party. China, the emerging global superpower, has become the number one trading partner for these nations, thereby deepening Beijing’s political influence in the Middle East.

Over the last decade, on average, China imported half of its oil from the region. In 2020, China imported $82.6 billion of oil from Persian Gulf countries. Unlike Western democracies, China is in no rush to divest from fossil fuels. As the demand for Persian Gulf oil fades in the West, Chinese imports play an even more critical role in the region’s economic life.

According to the World Bank, in 2000, trade between Saudi Arabia and the United States was $20.6 billion. Twenty years later, in 2020, it was $20.1 billion. By contrast, the trade between China and Saudi Arabia grew from $3.1 billion in 2000 to $67.1 billion in 2020.

The contrast becomes more evident in light of the disparities among American, Chinese, and Saudi Arabian imports and exports. U.S. exports to Saudi Arabia rose from $6.2 billion in 2000 to $11.1 billion in 2020, while its imports dropped from $14.4 billion in 2000 to $9 billion in 2020. China’s exports to and imports from Saudi Arabia have risen from under $2 billion each in 2000 to $28 billion in exports and $39 billion in imports in 2020.

The picture is clear: Chinese and Persian Gulf economies are becoming more integrated, while regional and U.S. economic interests are on diverging paths.

For decades, the United States backed the Arab monarchies in exchange for a stable flow of oil to Western democracies. Today, the United States is the largest oil producer, and Western democracies are planning to reduce their fossil fuel consumption. That old deal has lost its rationale.

China has exploited these developments to augment its own power. China now has a twenty-five-year cooperation pact with the Islamic Republic of Iran and is helping Saudi Arabia not just with its ambitious economic plans but also in developing its nascent nuclear program.

Additionally, the countries in the Persian Gulf may find China a better patron. The absolute monarchies, autocracies, theocracies, and enlightened despots of the region may find a kindred spirit in China and its communist party. At least for now, China does not lecture them on how to treat their citizens as long as they do not lecture China on how it treats its citizens, including the Muslim Uyghurs.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken with Saudi FM Faisal bin Farhan: In some ways, the Saudis and other Gulf monarchies may find China a more comfortable patron than the US, unlikely to pressure or criticise over human rights (Photo: Twitter).

Compared to the United States, China’s autocratic political system allows it a more consistent foreign policy. The Biden administration has paused, if not reversed, the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign against Tehran, removed the Houthis from the U.S. terrorism list, and increased pressure on Riyadh to end the war in Yemen. As a result, U.S. allies who strongly oppose these actions are diversifying their patrons—especially with China.

China wants to secure the flow of oil from the region. It seeks intelligence and political cooperation in the Middle East to provide a cover for Beijing’s persecution of Muslim minorities. And it aims to cultivate allies in its quest for global preeminence.

If the United States decides to keep retrenching in the Middle East, China will likely fill the gap. The region offers unrivaled energy resources and rising Chinese power there would grant Beijing more potential leverage over its rivals.

American proponents of abandoning the Persian Gulf often cite the need to pivot to Asia. However, Washington’s retreat from the region may achieve the exact opposite of U.S. objectives, ultimately emboldening and empowering China.

Saeed Ghasseminejad is a senior advisor on Iran and financial economics at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD), Follow Saeed on Twitter @SGhasseminejad. FDD is a Washington, DC-based, non-partisan research institute focusing on national security and foreign policy.

As the U.S. Pulls Back From the Mideast, China Leans In

China is expanding its ties to Middle Eastern states with vast infrastructure investments and cooperation on technology and security.

By Ben Hubbard and Amy Qin

New York Times, Feb. 1, 2022

The alleged Chinese genocide against the Muslim Uyghur minority seems to be having no effect on the rush of Middle Eastern government leaders to China, with most leaders and diplomats not even raising the issue (Photo: Shutterstock, Karl Nesh).

BEIRUT, Lebanon — In January alone, five senior officials from oil-rich Arab monarchies visited China to discuss cooperation on energy and infrastructure. Turkey’s top diplomat vowed to stamp out “media reports targeting China” in the Turkish news media, and Iran’s foreign minister pressed for progress on $400 billion of investment that China has promised his country.

As the United States, fatigued by decades of war and upheaval in the Middle East, seeks to limit its involvement there, China is deepening its ties with both friends and foes of Washington across the region.

China is nowhere near rivaling the United States’ vast involvement in the Middle East. But states there are increasingly looking to China not just to buy their oil, but to invest in their infrastructure and cooperate on technology and security, a trend that could accelerate as the United States pulls back.

For Beijing, the recent turmoil in neighboring countries like Afghanistan and Kazakhstan has reinforced its desire to cultivate stable ties in the region. The outreach follows the American military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan after 20 years, as well as the official end of its combat mission in Iraq. That, along with the Biden administration’s frequent talk of China as its top national security priority, has left many of its partners in the Middle East believing that Washington’s attention lies elsewhere.

Beijing has welcomed the chance to extend its influence, and Arab leaders appreciate that China — which touts the virtue of “noninterference” in other countries’ affairs — won’t get involved in their domestic politics or send its military to topple unfriendly dictators. And each side can count on the other to overlook its human rights abuses.

“There is a feeling in the region that the United States is actively on the way out, and that’s an opportunity for China,” said Gedaliah Afterman, head of the Asia Policy Program at the Abba Eban Institute of International Diplomacy at Reichman University in Israel.

China’s interest in the Middle East has long been rooted in its need for oil. It buys nearly half of its crude from Arab states, with Saudi Arabia topping the list, and it is sure to need more as its economy, the world’s second largest, keeps growing.

But in recent years, China has also been investing in critical infrastructure in the region and making deals to supply countries there with telecommunications and military technology.

Chinese state-backed companies are eyeing investments in a maritime port in Chabahar, Iran. They have helped to finance an industrial park in the port of Duqm, Oman, and to build and operate a container terminal in Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates’ capital, as well as two new ports in Israel.

Such moves reflect Beijing’s view of the Middle East as crucial to its Belt and Road Initiative, a sweeping plan to build international infrastructure to facilitate Chinese commerce.

China hopes to link markets and supply chains from the Indian Ocean to Eurasia, making the Persian Gulf region “a really important hub,” said Jonathan Fulton, a nonresident senior fellow for Middle East programs at the Atlantic Council.

Dr. Gedaliah Afterman, head of the Asia Policy Programme at the Abba Eban Institute for International Diplomacy at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (and former AIJAC staffer): “There is a feeling in the region that the United States is actively on the way out, and that’s an opportunity for China.”

In its business-focused dealings in the region, China has not directly confronted the United States. But it often promotes itself as an alternative partner for countries that question Washington’s model of development, or its history of political and military interventions.

“At a time when United States is facing ups and downs in its domestic and foreign policies, these countries feel that China is not only the most stable country, but also the most reliable,” said Li Guofu, a researcher at the China Institute of International Studies, which is overseen by the Chinese Foreign Ministry.

China’s main interests in the region are economic, but its growing ties have also brought it political dividends. Middle Eastern states have stayed mum on issues like Beijing’s quashing of political freedoms in Hong Kong and its menacing moves toward Taiwan.

Perhaps more surprisingly, given their majority-Muslim populations, almost none have publicly criticized China’s forced internment and indoctrination of its Muslim Uyghur minority, which the United States has deemed genocide. Some Arab states have even deported Uyghurs to China, ignoring concerns that they could be tortured or killed.

Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur activist in Norway, said two Chinese citizens had been detained in Saudi Arabia after one called for violent resistance to China’s repression. The two men were told they would be returned to China, Mr. Ayup said. Their current whereabouts are unknown.

Mr. Ayup said he knew of individual Uyghurs who had been deported from Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and other Arab states. He said five were sent to China from Saudi Arabia, which has historically portrayed itself as a defender of Muslims worldwide.

“They are not servants to the two holy places,” Mr. Ayup said, referring to the Saudi king’s official title as overseer of Islam’s holiest sites. “They are servants to the Chinese Communist Party.”

Of China’s recent diplomatic visitors from the region, only the Turkish foreign minister, Mevlut Cavusoglu, raised the issue of the Uyghurs, according to official accounts of the meetings.

For Middle Eastern countries, the benefits of the relationship are clear: China promises to be a long-term buyer of oil and gas and a potential source of investment, without the political complications involved in doing business with the United States.

Beijing deals with governments that Washington spurns. Syria, whose leaders are under heavy sanctions for atrocities committed during its civil war, just joined the Belt and Road Initiative. And Iran has become heavily reliant on China since the United States withdrew from the international deal to restrict Iran’s nuclear program and reimposed sanctions that have crippled its economy.

But China’s most extensive regional ties are with the Arab oil giants of the Gulf, led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

China is the largest trading partner of many countries in the region, and they expect it to buy more of their oil and gas as the United States, which under the Biden administration has sought to shift away from fossil fuels, buys less. Last year, trade between China and the Gulf States exceeded $200 billion for the first time, and cooperation has expanded to new realms.

Bahrain and the Emirates were the first countries to approve Chinese-made coronavirus vaccines, and the Emirates partnered with Chinese companies to produce them.

In China’s official summaries of the January meetings, the warmest praise was reserved for Saudi Arabia, which China called a “good friend,” “good partner” and “good brother.” On Wednesday, top defense officials from China and Saudi Arabia held a virtual meeting to discuss ways to deepen the countries’ military ties.

The Emirates, which wants to increase its standing as a tech and financial hub, is particularly interested in Chinese companies. “There are a lot of Chinese tech firms that are now at the cutting edge that are trying to go global, and they can’t go into the United States or Europe because of regulations,” said Eyck Freymann, a doctoral candidate in China studies at Oxford University.

He gave the example of SenseTime, a Chinese company that has been criticized by rights groups and blacklisted by the United States for supplying Beijing with technologies used to profile Uyghurs. That has not deterred Arab customers: In 2019, SenseTime opened a regional headquarters in Abu Dhabi.

“In every Middle Eastern country, their public security bureau wants that, and the Chinese are offering that product,” Mr. Freymann said.

The United States has tried to block some Chinese moves into the region, particularly infrastructure upgrades by the telecoms giant Huawei, which Washington warns could facilitate Chinese espionage. Some Arab countries have struck deals with Huawei anyway.

Over time, analysts say, China’s aversion to regional politics and conflict could hinder its outreach to the Middle East, rife as it is with wars, uprisings and sectarian tensions. China has made no effort to emulate the American security presence there, and the United States’ Arab partners have tried to engage with China in ways that do not alienate Washington.

“The Gulf States have been careful to balance their approach to ensure that growing ties with China do not antagonize their main security guarantor, the United States,” said Elham Fakhro, a visiting scholar at the Center for Gulf Studies at Exeter University.

Ben Hubbard reported from Beirut, Lebanon, and Amy Qin from Taipei, Taiwan. Asmaa al-Omar contributed reporting from Beirut and Amy Chang Chien from Taipei, Taiwan.

Ben Hubbard is the Beirut bureau chief. He has spent more than a dozen years in the Arab world, including Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Yemen. He is the author of “MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman.” @NYTBen. Amy Qin is an international correspondent covering the intersection of culture, politics and society in China. @amyyqin

The Middle East at the Olympics

Six Countries Compete While Great Power Politics on Display

by Carol Silber

Feb 9, 2022

Because regional leaders are treating the games as another stage for balancing historic partnerships with current economic and security interests, Washington should keep drawing clear lines regarding their ties with Beijing.

Most foreign leaders boycotted the Beijing Winter Olympics this month – but three Middle Eastern leaders from Egypt, Qatar and the UAE were among those who did attend (Photo: Wikimedia Commons | Licence details).

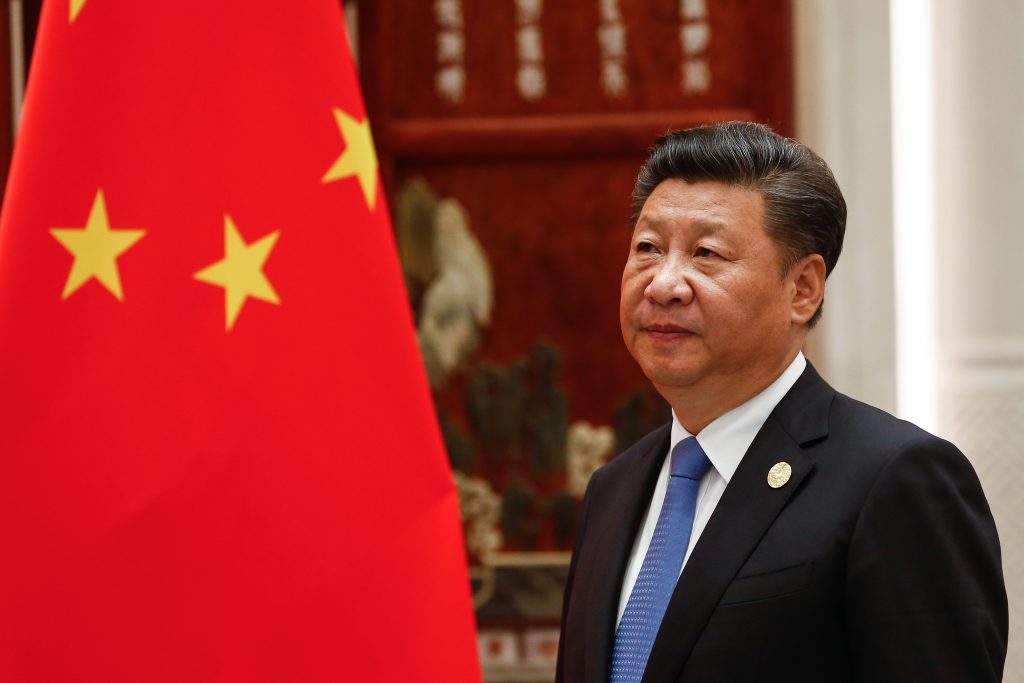

Three weeks after Middle Eastern officials made headlines by traveling to China for high-level meetings, the leaders of three Arab states—Egyptian president Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, Qatari emir Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani, and de facto Emirati ruler Muhammad bin Zayed—arrived in Beijing to attend the Olympic Winter Games. President Xi Jinping held individual talks with each leader over the weekend and expressed eagerness to deepen cooperation with their countries. According to Chinese state media, he pledged to further promote the Belt and Road Initiative in Egypt, enhance energy ties with Qatar, and speed up free trade negotiations with Gulf countries.

The games have also become a forum for heightened engagement between Gulf governments, with the leaders of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates joining President Xi for a mutual luncheon on February 5. It was the first such interaction between the two leaders since the UAE, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain ended their long-running diplomatic rift with Qatar last year.

Initially, media reports indicated that de facto Saudi ruler Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman would attend the opening ceremonies as well, but the only Saudi officials present were Princess Reema bint Bandar and Prince Abdulaziz bin Turki al-Faisal, the kingdom’s ambassador to the United States and minister of sport, respectively. Saudi press statements did not mention the crown prince’s apparent absence, which was possibly an outcome of U.S. pressure. Two days after the ceremony, China’s Foreign Ministry stated that he did not attend due to “his schedule.”

For its part, the Israeli government did not send any officials to the games. Minister of Culture and Sport Hili Tropper declined Beijing’s invitation, citing concern about the ongoing wave of COVID-19’s Omicron variant. No states from the region officially announced that they would be joining the U.S.-led diplomatic boycott of the event (discussed below).

Middle Eastern Athletes at the Games

Although every country in the Middle East and North Africa has participated in the Summer Olympic Games, their attendance at Winter Games is less common. This year, six countries are participating: Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. They sent 19 athletes in total, a tiny fraction of this year’s 2,871 Olympians. No country from the region has ever won a winter medal, and that track record has continued so far at the Beijing games.

Saudi Arabia is making its winter debut, sending alpine skier Fayik Abdi as its only Olympian at these games. Two years ago, the kingdom formed the Saudi Winter Sports Federation (SWSF) as part of a wider effort to expand its cultural and entertainment sectors under the Vision 2030 plan. In early 2021, the SWSF stated that it was seeking Saudis who could qualify for the Winter Games, then offered to fund Abdi’s training. The twenty-four-year-old athlete was born in San Diego but spent his childhood in Saudi Arabia, learning to ski in Lebanon and Switzerland before starting college in Utah, where he hit the slopes frequently. When he returned to the kingdom after graduating in 2020, he planned to pursue sand skiing but was contacted by the SWSF and began training for the games.

As for the other countries in attendance, Iran has participated in the Winter Olympics eleven times since its 1956 debut and sent two alpine skiers this year. Israel has sent a delegation to every Winter Games since 1994; this year it has two alpine skiers, three figure skaters, and one short-track speed skater competing. Lebanon has participated in nearly every Winter Games since its 1948 debut; it sent two alpine skiers and one cross-country skier this year. Morocco has participated in seven Winter Olympics since its 1968 debut and is represented by one alpine skier in Beijing. Turkey has participated in nearly every Winter Olympics since 1936; its current delegation includes two alpine skiers, three cross-country skiers, one short-track speed skater, and one ski jumper. Two other regional countries have participated in previous years despite not making the Beijing games: Algeria attended the 1992, 2006, and 2010 Winter Olympics, while Egypt attended in 1984.

Implications for U.S. Policy

As mentioned previously, top officials from Iran, Turkey, and four Gulf countries flew to China in the weeks leading up to the games to discuss further cooperation on economics, infrastructure, energy, and other sectors. This flurry of diplomatic activity came amid heightened scrutiny of Beijing’s ties to the Middle East. In late 2021, for example, reports alleged that China was assisting Saudi Arabia with its ballistic missile program, while U.S. intelligence assessed that a secret Chinese military outpost was being built at an Emirati port, prompting Abu Dhabi to halt construction.

Recent U.S. reactions to Chinese investments in Israel may indicate how the Biden administration will respond if America’s other regional partners continue advancing their ties with Beijing. According to senior Israeli officials, the country rejected bids from two Chinese companies for light rail construction in Tel Aviv amid pressure from the United States. Similar tactics may prove necessary in the future as the administration attempts to keep allies in its fold while simultaneously shifting its focus away from the Middle East.

The attendance at the Beijing Olympics of three prominent Arab leaders in the face of the US-led Boycott is a boost for President Xi’s agenda and prestige. (Photo: Shutterstock, Wirestock Creators).

Regarding Chinese meetings with regional leaders in Beijing, various obstacles may impede both sides from translating this engagement into implemented agreements and enhanced partnerships. U.S. allies could prove hesitant to anger the Biden administration, while China may prefer to focus deeper diplomatic engagement on the Asia-Pacific region, among other considerations.

Still, the fact that three prominent Gulf leaders attended the games amid a U.S. diplomatic boycott is a boon for President Xi’s agenda and prestige. In recent years, some Middle Eastern officials have refused to condemn what the United States refers to as China’s genocidal policies toward the Uyghur Muslim population in Xinjiang. It therefore comes as no surprise that they did not buy into a U.S.-led boycott centered on that issue.

The international reaction to the current boycott contrasts sharply with the 1980 Moscow games, when fifty-four countries joined Washington in pulling out of the competition entirely to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The list included Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Turkey, and Tunisia—and China.

With international tensions at urgent levels amid shifting global tides, leaders in the Middle East are clearly treating the Olympics as another stage for staking out their positions and balancing historic partnerships with their current economic and security interests. As with the light rail project in Israel, Washington must continue balancing two of its own primary objectives in the region: warning traditional partners about advancing ties with Beijing while sustaining a reputation as a trustworthy ally.

Carol Silber is a research assistant with The Washington Institute’s Fikra Forum.

Tags: China, Middle East