UPDATES

A China-Iran Alliance?

July 17, 2020 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

07/20 #02

This Update deals with the implications of reports that Iran and China have completed negotiations on an agreement that would turn the two countries into close economic partners and military allies, with the New York Times releasing a purported final text of the agreement said to be set to be signed early next year. It involves US$400 billion in investment by China in Iran in exchange for discount oil over 25 years, as well as military cooperation, including weapons development and intel sharing.

We lead with Israeli security affairs journalist Seth Frantzman, who says the agreement seems to be part of a larger tectonic shift across the Middle East, with numerous groups linked to the Iranian bloc seeking to exploit perceived US weakness in the region by bolstering Beijing. He says China has moved cautiously in the Middle East until now, and may continue to do so, especially by working together with Russia and Iran, but that Iranian allies including Syria, Iraq and Lebanon are hungry for deals with China. However, in Iran itself there is some concern about aligning with China, he reports. For more on the regional context of the Iran-China deal, CLICK HERE.

Next up is Lahav Harkov, diplomatic correspondent at the Jerusalem Post, who explores the Israeli view on an Iran-China deal. She identifies at least three different ways this deal would raise serious concerns for Israel – 1. Chinese money could ease the pressure Iran is feeling under the US policy of maximum pressure via sanctions, 2. “Any dollar going into the Iranian system is one that can likely be spent against Israel”; and 3. the deal envisions massive arms sales to Teheran, making it a much more formidable opponent as it seeks Israel’s destruction. She also discusses how the deal would fall into China’s opportunistic regional strategy. For all of her insights, CLICK HERE.

Finally, Golnaz Esfandiari, Iran reporter at Radio Free Europe, looks in more depth at the internal debates in Iran about a deal for a close alliance with China. He notes that critics in Iran are arguing that Iran is coming from a place of weakness and getting into an unequal partnership – which is probably not inaccurate – and the treaty is also opposed by hardliner nationalists like former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Meanwhile, Iranian trust in their leadership is very low in the face of the crackdown on demonstrators last year and the shooting down of a Ukrainian passenger plane filled mostly with Iranians early this year (and indeed anti-regime protests have reappeared again this week). For Esfandiari’s knowledgeable analysis, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- More good analysis of the mooted China-Iran deal by experts Stephen Blank and Ali Alfoneh.

- Meanwhile, Michael Rubin argues it is incorrect to characterise the deal as directed against the Trump Administration, as its roots predate Trump’s election.

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director-General Rafael Mariano Grossi gives Iran until the end of the month to comply with obligations to allow access to sites the IAEA wants to inspect.

- Iranian proxy Hezbollah hopes that China will also bail Lebanon out of its current economic disaster – even as Hezbollah is also now indicating it will also allow Lebanon to take money from its “enemy”, the US.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Jack Gross on the coronavirus second wave faced by the Palestinian Authority.

- Oved Lobel on how Iran has deepened its close ideological, political, economic, and military relations with Nicolas Maduro’s Venezuela.

- AIJAC’s Ahron Shapiro on “Black Lives Matter and the scourge of antisemitism” in The Spectator.

- The Powerbroker, a new biography of AIJAC National Chairman Mark Leibler, written by veteran journalist Michael Gawenda, is being launched by former Prime Minister of Australia, the Hon Julia Gillard AC and indigenous activist, Mr Noel Pearson, on Monday 20 July 2020 at 6pm sharp. To view the launch, click here then: https://www.monash.edu/news/events/launch-of-michael-gawendas-latest-book.

- AIJAC’s latest webinar guest was Danielle Pletka, a senior fellow in foreign and defence policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), speaking on the subject of “Trump vs Biden: The Future of US Foreign Policy”. Video is here, and a written report on her discussion is here. A short video excerpt highlights Pletka’s comments on the Trump Administration’s policy on Iran.

- Recent AIJAC webinar guest Jonathan Spyer discussed the current mysterious wave of explosions in Iran on the “Bolt” show on SkyNews.

Iran’s Turn to China

By SETH J. FRANTZMAN

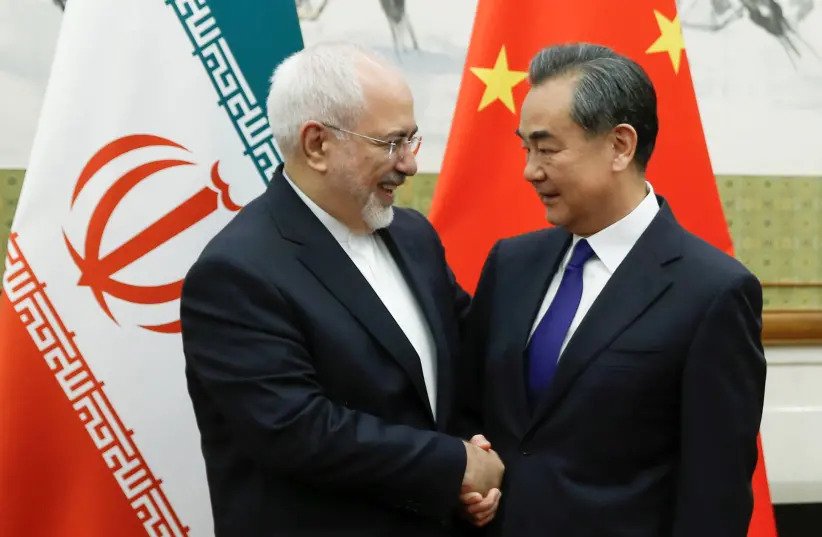

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Iranian counterpart Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif hold talks in Beijing, Dec. 31, 2019. (Kyodo via AP Images)

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and his Iranian counterpart Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif hold talks in Beijing, Dec. 31, 2019. (Kyodo via AP Images)

A secret deal between Iran and China is in the works, part of a wider 25-year strategic vision between the two countries. Such rumors percolated in Tehran in early July at the same time that Iran was being bombarded by mysterious explosions affecting its missile and nuclear programs. The Iranian regime’s media, particularly voices and media close to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, have tried to affirm that the rumors are true and that the new shift east is a strategic challenge to the U.S. in the Middle East. The regime is also downplaying other rumors that Iran is giving away islands and slices of its economy to bring Beijing in the door.

The Iranian shift to China is part of a tectonic movement across the Middle East. Countries and groups linked to Iran now seek to exploit perceived U.S. weakness as an opportunity to get around Washington’s sanctions and to bolster Beijing. The long-term consequences are grave. China has already sought to influence other U.S. allies, such as Israel, through infrastructure projects, including port and desalination deals. Beijing has also sold drones to key U.S. partners, such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Jordan. Now China senses an opportunity to embrace Tehran, along with Iran’s allies in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.

Tehran’s decision to shift toward China comes in the context of unprecedented sanctions under Washington’s maximum-pressure campaign. With the U.S. Navy intercepting Iran’s shipments of weapons to its Houthi rebel allies and Israel striking Iranian precision-guidance munitions on the way to Hezbollah via Syria, Iran is in desperate need of stronger allies. It has found support at the U.N. Security Council from Russia and China on the upcoming expiration of an arms embargo. It has also been able to ship at least nine tankers full of gas to Venezuela. But these are drops in the economic bucket compared with what China could provide. Thus the IRGC, which controls much of Iran’s ballistic-missile and drone programs, as well as foreign and military policy and parts of Iran’s economy, is hyping the new strategic deal with China via Iranian media outlets. On July 13, Fars News and Tasnim networks bragged that Iran had outwitted Washington.

What is at stake here? Iran–China relations are multi-layered. First, those in Iran’s regime who prefer China have accused president Hassan Rouhani and foreign minister Javad Zarif of being too supplicating towards the West. At the same time, there are more far-right nationalist voices, such as former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejed, who infer that deals with China will sell out Iran’s resources. All of this has played out unusually in Iran’s media, which, despite being controlled by the regime, are not a complete monolith and sometimes reflect the regime’s inner struggles. For instance, a July 10 Fars News article in Iran asserted that “westernization” of Iran’s foreign policy was preventing the move to China.

After weeks of internal discussions, Iran’s Foreign Ministry says the country is ready for a roadmap that underpins more than two decades of economic Iran–China cooperation. More important, Iran’s allies in the region are also now shifting towards China. Beijing has long touted its Belt and Road Initiative across the region as a way to link China via Iran to Europe. Iraq, whose government is dominated by pro-Iranian political parties, has also sought out mega-deals with Iran on oil and reconstruction in the last several years. China could play a larger role in the reconstruction of Syria as well. Syria’s regime is an ally of Iran, and the two countries signed an air-defense pact on July 8.

Hezbollah head and loyal Iranian proxy Hassan Nasrallah is urging Lebanon to follow Iran and look to China

Hezbollah head and loyal Iranian proxy Hassan Nasrallah is urging Lebanon to follow Iran and look to China

Emblematic of the shift to China among Iran’s octopus-like allies in the region is the speech by Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah on July 7. “If you want to see the effectiveness of the Chinese offer, look at the angry American response,” he thundered, describing recent overtures by Beijing to Beirut. Nasrallah says Lebanon must turn east. He said this as he threatened the U.S. ambassador in Beirut, and on the eve of the visit by CENTCOM commander Kenneth McKenzie to Lebanon.

Until now, China has moved cautiously in the Middle East. For example, it conducted a naval exercise with Russia and Iran in December 2019. However, in general, China’s main interest is to bide its time and seek out beneficial economic and infrastructure deals. Increasing clashes with the U.S. may encourage China to move faster to help Iran.

Countries such as Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Iran are hungry for deals with Beijing. As the U.S. considers withdrawing from Syria and repositioning troops in Iraq, the opening to Beijing is widening. China likely prefers to work with Iran and Russia because it can combine its abilities well with theirs. Russia provides the heavy lifting at the U.N. and troops on the ground in Syria while China does the infrastructure and Iran works with local religious communities to influence Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon. To counteract the Iran–China partnership, Washington will need to move quickly to shore up allies and support in the Gulf, among other places.

The Iran–China connection already exists. But for now, Iran may be a net economic loss for China because countries such as Iran and its allies in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon are in economic disarray. That means China would plow investment in without much to show for it initially. The U.S. already plowed investment into Iraq after 2003 and it came to little, due to an active insurgency and later ISIS. Thus, China will move cautiously. It doesn’t want to become a party to a local conflict, but prefers to be seen as a benevolent economic giant willing to work with everyone. In Iran, China and the U.S. might be choosing sides for a wider coming conflict.

SETH J. FRANTZMAN is the author of AFTER ISIS: AMERICA, IRAN, AND THE STRUGGLE FOR THE MIDDLE EAST (2019) and serves as the executive director of the Middle East Center for Reporting and Analysis. He is the Middle East affairs correspondent for the Jerusalem Post and a writing fellow at Middle East Forum.

Proposed China-Iran deal is bad news for Israel

The American “maximum pressure” campaign has clearly had a major impact on Iran, but a massive influx of Chinese investments will go a long way towards undoing it.

By LAHAV HARKOV

Jerusalem Post, JULY 14, 2020 10:11

Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, greets Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Qingdao in eastern China’s Shandong Province on June 10, 2018. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

Chinese President Xi Jinping, left, greets Iranian President Hassan Rouhani at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit in Qingdao in eastern China’s Shandong Province on June 10, 2018. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

With Iran and China working on a multibillion-dollar 25-year economic and security deal, Israel has many reasons to be concerned and even alarmed.

The proposed agreement, leaked to The New York Times, which reported on it on Saturday, would lead to a closer military relationship between Tehran and Beijing, including joint military exercises, research and weapons development and intelligence sharing. It would also increase Chinese investments in Iranian banking, telecommunications and transportation, such as airports and railways. China would reportedly get a discounted supply of Iranian oil in return.

The document describes the countries as “two ancient Asian countries… with a similar outlook” that “will consider one another strategic partners.”Neither side has publicly confirmed that the document is genuine, that they have signed it or that there is any such agreement. When asked about a deal with Iran last week, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said: “China and Iran enjoy traditional friendship, and the two sides have been in communication on the development of bilateral relations. We stand ready to work with Iran to steadily advance practical cooperation.”Meanwhile, there is public debate in Iran about whether the agreement could be a debt trap, with former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad speaking out against it. The agreement has been in the works for a long time – Chinese leader Xi Jinping first proposed it on a visit to Tehran in 2016 – and the timing for the recent progress likely has to do with Iran being especially economically weak these days.

According to Carice Witte, executive director of SIGNAL, a think tank focused on China-Israel relations: “This is indicative of the Chinese approach, [to] identify where there is a vulnerability and then patiently look for ways to capitalize on it.”

China has much to gain from the deal besides a discount on gas when energy prices are plummeting anyway. The agreement fits into China’s Belt and Road Initiative to build infrastructure across the world, while bringing Iran into its orbit of influence. It also would bolster China’s new digital currency e-RMB as a way to bypass American systems and reduce the power of the dollar – another way in which the deal could hurt Israel if it comes to fruition.

Plus, China would gain power and influence in Iran, a diplomatic card it can play with respect to the US and garner greater leverage in the Gulf.

For Israel, the potential for damage from such an agreement is clear.

Carice Witte, executive director of SIGNAL, a think tank focused on China-Israel relations

Carice Witte, executive director of SIGNAL, a think tank focused on China-Israel relations

AS WITTE said, “Any dollar going into the Iranian system is one that can likely be spent against Israel.”This is especially clear when it comes to the bolstering of Iran’s military through cooperation with China. Any of the new resources directed to the Islamic Republic’s army can potentially – and likely will – be turned on Israel.

Another part of the deal may be a massive sale of weapons to Iran. A recent Pentagon report said China seeks to sell Iran attack helicopters, fighter jets, tanks and more once the UN arms embargo expires in October.

While Israelis and Israel supporters may find it hard to believe, the Chinese government truly does not think Iran is a danger to Israel, Witte said.“China’s perception is that Iran doesn’t mean what it says about destroying Israel,” she said. “China does not see Iran as an existential threat to Israel and that Iran is only saying [it wants to destroy Israel] to be taken seriously by the world’s power centers.

”Israel and the US have been pushing UN Security Council members to extend the arms embargo on Iran that began under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers. Israel and the US have cited Tehran’s violations of that deal and continued attempts to build up its nuclear program, for which the International Atomic Energy Agency has repeatedly rapped Iran in recent weeks, as well as its sponsorship of terrorism and warfare through proxies around the Middle East.

But Chinese Ambassador to the UN Zhang Jun last week said his country opposes US attempts to activate the JCPOA’s “snapback sanctions” mechanism.

The return of US sanctions in 2018 has led to a major economic crisis in Iran and subsequent political instability. This empowered hard-liners to say Iran never should have made a deal involving the US in the first place. They won a decisive majority of Iran’s parliament in an election this year.

But it also has led to protesters taking to the streets this year, protesting a government that uses its money to pay for wars in other countries instead of helping its own people. Experts say the regime is as unpopular as it has ever been since the Islamic Revolution.

The US “maximum pressure” campaign has clearly had a major impact on Iran, but a massive influx of Chinese investments will go a long way toward undoing it, effectively relieving the pressure.

Another concern is regarding Chinese companies’ involvement in infrastructure projects in Israel and Iran. This is already taking place, but the 25-year agreement would deepen those ties.

A Jerusalem Post investigation last month found that three of the six international groups bidding on the tender to build two lines of the Tel Aviv light rail include Chinese-owned companies that also worked on railway projects in Iran. These state-owned companies include China Railway Engineering Corporation, China Harbour Engineering Company, China Communications Construction Company and its China Railway Construction Corporation.

A report by the RAND research institute this year warned that due to China’s close ties with Iran, the Chinese government could have companies share insights on Israel with Tehran to gain favor and influence. In addition, China could use the companies operating in Israel and Iran for political leverage on Israel, such as in 2013, when it conditioned a Beijing visit by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on his stopping defense officials from testifying in a New York federal lawsuit against the Bank of China for laundering Iranian money for Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad.

The US is waiting to see what actual agreement emerges, and it will continue to take action against any Chinese company breaking sanctions, a State Department source said. For example, the US is pursuing criminal charges against Chinese telecom company Huawei’s CFO Meng Wanzhou for attempting to avoid US sanctions by hiding investments in Iran.

The Prime Minister’s Office declined to comment on this matter, but it is likely eyeing the China-Iran agreement with concern.

Explainer: Why Are Iranians Angry Over A Long-Term Deal With China?

By Golnaz Esfandiari

Radio Free Europe, July 13, 2020

Anti-regime protestors in Behbehan, Iran, this week: Amid popular unrest, the China deal looks likely to be another grievance for critics of the clerical regime

Anti-regime protestors in Behbehan, Iran, this week: Amid popular unrest, the China deal looks likely to be another grievance for critics of the clerical regime

Iran is negotiating a controversial 25-year agreement with China that has led to accusations that parts of Iran are being sold to Beijing.

Some critics — including the U.S. State Department — are comparing the proposed deal to the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay between Persia and tsarist Russia, under which the Persians ceded control of territory in the South Caucasus.

Iranian officials have dismissed the criticism as baseless while promising to make the text of the agreement public once it is finalized.

What Do We Know About The Agreement?

The pact was proposed in a January 2016 trip to Iran by Chinese President Xi Jinping during which the two sides agreed to establish their ties based on a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, while announcing discussions would begin aimed at concluding a 25-year bilateral pact.

The announcement received the support of Iran’s highest authority, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who was quoted by Iranian media as saying that the agreement reached between the two sides was “wise.”

The text of the agreement, which will need to be approved by parliament, has not been released. But in recent days an 18-page document has been making the rounds on social media that outlines future cooperation between the countries, including Chinese investment in Iran’s energy sector as well as in the country’s free-trade zones.

RFE/RL cannot verify the authenticity of the document, which has been cited by some Iranian and Western media as a leaked version of the planned pact between Iran and China.

Analysts note the agreement being circulated is very light on details and appears to be the framework of a potential deal.

According to the text, which is labeled “final edit” on its front page and dated the Iranian month of Khordad — which starts May 21 and ends June 19 — the two sides will also increase military and security cooperation while working on joint-projects in third countries.

Iran has in recent months increasingly reached out to China in the face of growing U.S. pressure to isolate Tehran. China remains Iran’s main trading partner but trade between the two sides has dropped due to U.S. pressure in recent years.

Analysts say China is not ready to give Tehran the support it seeks while also suggesting that some of the cooperation envisaged in the pact may never materialize.

Ariane Tabatabai, a Middle East fellow at the Alliance for Securing Democracy at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, said, given its importance, the U.S. will always trump Iran for China.

“Iran is a small, risky market, sanctions have severely impeded business [there], and the regime is isolated,” she told RFE/RL. “Meanwhile, China has major economic interests in the U.S. and the trade war is still an important concern for China, which will inevitably shape its relationship with Iran.”

“If we look into what we know about the document and make some educated guesses, we see that the agreement is little more than a comprehensive road map based on the 2016 framework, which does not resolve the main issue of the China-Iran partnership — its implementation,” Jacopo Scita, an Al-Sabah doctoral fellow at Durham University, told RFE/RL.

Why Is The Treaty Controversial?

The pact is being discussed at a time when Iran is under intense pressure due to harsh U.S. sanctions that have crippled the economy and a deadly coronavirus pandemic that has worsened the economic situation.

The timing as well as the scope and duration of the agreement has led to increased concerns that Tehran is negotiating with China from a position of weakness while giving Beijing access to Iran’s natural resources for many years to come.

A distrust in the Iranian authorities that intensified after a deadly November crackdown on antiestablishment protests and the downing of a Ukrainian passenger jet — which was initially seen as a coverup — has also contributed to the criticism of the proposed deal.

A lack of trust in China, as well as rising anti-China sentiments due to the coronavirus pandemic, has also contributed to the controversy surrounding the pact.

Tabatabai, the co-author of a book on Iranian ties with Russia and China, says the relationship between Tehran and Beijing has long been perceived as benefiting China far more than Iran.

“The perception isn’t fully inaccurate,” she said. “From the elite’s perspective, China makes big promises and delivers little. And from the population’s perspective, China has been benefiting from the sanctions on Iran, it’s flooded the Iranian market, pushed out Iranian businesses, and has delivered products that are subpar.”

She added: “Many Iranians feel like this deal will cement this unbalanced relationship.”

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has been among those who have criticized the putative deal.

Former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has been among those who have criticized the putative deal.

What Are The Critics Saying?

Criticism of the planned pact appears to have increased following comments by former President Mahmud Ahmadinejad, who warned in a speech in late June that a 25-year agreement with “a foreign country” was being discussed “away from the eyes of the Iranian nation.”

Others have since joined the criticism, including former conservative lawmaker Ali Motahari, who appeared to suggest on Twitter that before signing the pact Iran should raise the fate of Muslims who are reportedly being persecuted in China.

Scita, who closely follows Iranian-Chinese relations, says some of the hype and anger surrounding the agreement were boosted by public figures with political agendas, including Ahmadinejad, who is said to be eying the 2021 presidential election.

The exiled son of the shah of Iran, the country’s last monarch who was ousted following the 1979 Islamic Revolution, has also criticized the pact.

Reza Pahlavi, who’s taken an increasingly active role against the Islamic republic, blasted the “shameful, 25-year treaty with China that plunders our natural resources and places foreign soldiers on our soil.” He also called on his supporters to oppose the treaty.

The Persian account of the U.S. State Department referred to the planned agreement as a “second Turkmenchay” and said that Tehran is afraid to share the details of the pact because “no part of it is beneficial to the Iranian people.”

What Are Iranian Officials Saying?

Earlier this month, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif confirmed that Tehran was negotiating an agreement with China “with confidence and conviction,” while insisting there was nothing secret about it.

Since then, officials have defended the deal while dismissing claims that Iran will sell discounted oil to China or give Kish Island to Beijing.

President Hassan Rohani’s chief of staff, Mahmud Vaezi, said over the weekend that the framework of the agreement has been defined, adding that the negotiations are likely to be finalized by March 21.

Vaezi also said the agreement does not include foreign control over any Iranian islands or the deployment of Chinese military forces in the country.