UPDATES

Amnesty’s response to atrocities in Syria: “International community must act”… with yet more empty words

June 20, 2012 | Or Avi Guy

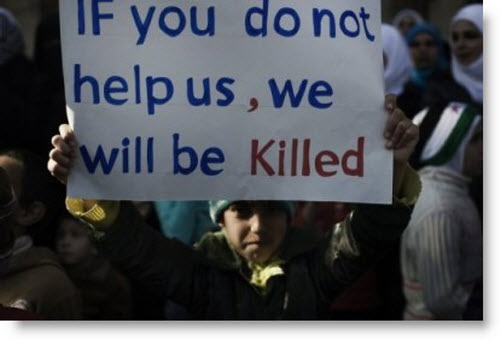

After more than a year of brutal repression of anti-regime protest, the atrocities against civilians in Syria keep reaching new heights. Growing attention to the bloodshed and violence in that country by the international community and human rights organisations, even if tragically belated, could have been a hopeful sign that something might finally be done to put an end to the bloodshed. In reality, however, no such steps appear to be in sight.

Amnesty International recently released a new report titled “Deadly Reprisals: deliberate killings and other abuses by Syria’s armed forces,” after engaging in covert fieldwork in north-eastern Syria. The report describes in harsh words the systematic and deliberate killing of civilians by Assad’s forces in towns that are suspected of supporting opposition forces, indiscriminate attacks (often resulting in civilian casualties), torture, arbitrary detention and destruction of homes and property. According to the report, these acts amount to crimes against humanity and are in gross violation of international humanitarian, human rights and criminal laws.

Amnesty International researcher Donatella Rovera described the desperate situation in Syria: “Everywhere I went I met distraught residents who asked why the world is standing by and doing nothing… Such inaction by the international community ultimately encourages further abuses. As the situation continues to deteriorate and the civilian death toll rises daily, the international community must act to stop the spiralling violence”.

But what does Amnesty International propose the international community should do in face of such heinous crimes? Amnesty’s strong words in diasgnosing the problem are followed only by weak recommendations for action, which look unlikely to do anything to restore security and halt the regime’s murderous spree – mainly because most of them are addressed to the Syrian regime itself.

Amnesty recognises in principle that addressing Assad’s regime is a futile exercise, as they themselves have observed that “it is manifestly evident that the Syrian Government has no intention of ending, let alone investigating, these crimes.” And yet, they go on and make the following suggestions to the Syrian regime: firstly they recommend that the Syrian Government stops all violations of international law and human rights such as extrajudicial executions, indiscriminate fire in civilian-populated areas, arbitrary arrests, torture etc. Then they recommend that all persons arbitrarily arrested should be released, and receive proper legal treatment and rights.

In other words, Amnesty seems to recommend that the solution to human rights abuses by the Syrian Government is that the Syrian Government should immediately cease all human rights abuses.

Continuing with that line of thought, Amnesty also recommends that the same government that is shelling entire neighbourhoods cooperate fully with the UN observer mission – granting monitors free access to its own detention facilities, etc. Full access to the country should be granted, according to Amnesty, to the independent international Commission of Inquiry and to international human rights monitors and humanitarian agencies.

One might think that it is both pointless and indeed, ridiculous at best or cynical at worst, to make such recommendations to the Syrian regime, which, as Amnesty itself admits, has no intentions to adopting them. At least no one can accuse Amnesty of not asking nicely.

Moreover, anyone who had hoped that the Amnesty recommendations for the international community would be more pragmatic, taking into consideration the severity of the atrocities, the lack of cooperation from the Syrian regime and the difficult international political situation, in which Russia and China block any attempt to hold the Syrian regime accountable, were in for a disappointment.

In another example of toothlessness, Amnesty called upon the UN Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC). Justified though this might be in terms of legality and morality, it raises at least two main problems: 1. It is unclear, at best, how such a decision could even be made, given both historical precedents (indictments against reigning governments are not exactly an everyday occurrence) and the virtual certainty of a Russo-Chinese veto; 2. How exactly could such a move deliver a prompt ending to the raging violence and prevent even more deaths of civilians, even if such a referral, by some miracle, were to be made? This seems to be far from the prompt and decisive international action the Amnesty’s interviewees mentioned by Rovera were hoping for.

The same kind of flawed logic appears in the recommendation that the international community will ‘demand’ that the regime grant access to humanitarian organisations and the international media (in case Assad was not convinced when it was suggested merely by Amnesty).

Another recommendation deals with the UN monitors mission. Amnesty in writing its report was preoccupied with terms of their mandate, which they suggested should include a human rights component and the “capacity to protect victims and witnesses.” This clause provides a perfect example of the remoteness of Amnesty’s recommendations from reality. Only a few days after the report was published and promoted internationally, the UN monitors announced that they had been forced to leave Syria and suspend their mission due to the intensity of the violence. The Amnesty document never bothered to explain which shape such a protection capacity on the part of the UN monitors would take – and no wonder. Protecting victims and witnesses? The monitors could not even protect themselves!

In addition, all of these recommendations require cooperation on behalf of the regime in order to be effectively implemented – which brings us back to the initial problem that Amnesty assumes that the lack of cooperation and political will within Assad’s regime will somehow miraculously be overcome if only the right formulation of words is used when asking the regime to stop the violence it is inflicting on Syrian civilians.

The fourth recommendation also faces difficult issues of lack of political will, but this time not from Syria itself, but from its supporters. Amnesty recommended that an arms embargo be imposed on Syria. Easy to say, but implementation is very unlikely, as it requires the cooperation of such compliant and internationally-responsible countries as Iran, Russia and China, with their impeccable human rights records. If it took Russia and China more than a year and approximately 10,000 dead to release a weak condemnation of the Syrian regime through the UN Security Council – it is hard to imagine that such an embargo will be in place anytime in the near future.

These recommendations, especially regarding the arms embargo, were also expressed by Amnesty’s Widney Brown on ABC’s Lateline last week (14.6.2012), who rejected the notions of international intervention and arming civilian groups for self-protection. By taking this stance – an effective arms embargo on both sides – Amnesty sends the distorted message that there is some symmetry or equivalence between the Syrian government and the opposition groups, and neither should be armed. However, as Widney even states during the interview, Assad’s forces already have the upper hand, and are disproportionally more powerful and better armed. In that case, stopping weapons’ supply will not change the balance of power and thus would only guarantee that the current slaughter can continue as long as the Syrian regime wants it to.

Amnesty is not the only one to suffer from the bark-but-never-bite syndrome. Foreign ministers from around the world seem to share Amnesty’s naivety, as they expressed support for the Annan Plan. According to the Plan a so-called cease-fire was announced in April, and while there was initially a slow-down in the killings, it has since become obvious that this was no more than a temporary lull. The U.N. monitors sent to supervise the implementation of the ceasefire and the rest of Annan’s six point plan are now gone, since the heavy bombardment of towns and massacres of civilians by the government proved too high risk for their mission to continue. Gen. Robert Mood, head of the U.N. Supervision Mission in Syria stated: “There has been an intensification of armed violence across Syria over the past 10 days… This escalation is limiting our ability to observe, verify, report as well as assist in local dialogue and stability projects — basically impeding our ability to carry out our mandate.” His forecast about the prospect of peace sounded bleak and he blamed the escalation in violence and civilians’ deaths on the “lack of willingness by the parties to seek a peaceful transition.”

In short, all the elements of the Plan – the ceasefire, the monitors, the transition plan to a new constitution – have all undeniably and irreversibly crumbled and yet, like the pet shop owner in Monty Python’s famous parrot sketch, world leaders continue to blindly insist that the Annan plan is not dead, but merely “resting”.

Hopes for Annan’s six point plan, much like Amnesty’s recommendations, always depended heavily on the good will and cooperation of the Syrian regime. Yet it has now become crystal clear that such hopes for the success of Annan’s Plan are not shared by the Syrian regime, which blamed “armed terrorist groups” for the suspension of the UN mission, despite going through great lengths to obstruct the mission and prevent monitors from reaching sites of heavy government shelling and other massacres. The Syrian Foreign Ministry blamed the armed groups who they claim “also disregarded Annan’s Plan and the initial agreement between the United Nations and the Syrian government, aided by Arab and international powers that are still providing the terrorists with up-to-date weapons and communication devices that help them in committing their crimes and sticking to their defiance of the U.N. plan.”

Meanwhile, opposition and human rights groups from within Syria are continuously calling for intervention. The estimated death toll is between 12,000 and 14,000 people and the fighting has now spread to the capital, Damascus, and its suburbs. The Local Coordination Committees (LCC) of Syria reported that “The city has been under a choking siege by the regime’s army… Local residents are issuing pleas for help for any sort of intervention to provide medical supplies to treat the wounded.” Another opposition group, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, made an “urgent appeal” to U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon “to immediately and personally intervene [in Homs neighbourhoods where] more than 1,000 families … are stranded (and) humanitarian conditions … are very difficult.”

It is time for everyone to recognise that responding to such appeals through the Amnesty/Annan model of finding new ways to again ask the regime to please stop, is the equivalent of telling a gun shot victim to “take two aspirin and call me in the morning.”

Or Avi-Guy

Tags: NGOs