UPDATES

Iranian Election dramas/ Western Apologists for Iran

May 17, 2013

Update from AIJAC

May 17, 2103

Number 05/13 #04

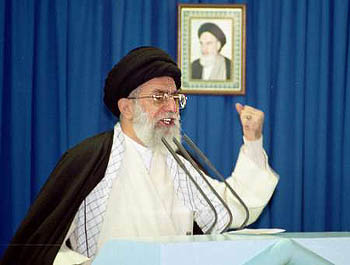

Western governments will be closely observing the Iranian election process in the leading up to the Presidential poll on June 14 in the hopes that the outcome may encourage a change that will allow a diplomatic resolution to the impasse over Iran’s nuclear program – though of course, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei is actually the key decisionmaker and is unaffected by the poll. The contest – which looked likely to be dominated by conservative Khamanei loyalists – was on May 11 rocked by the last minute entry of two candidates; former President Rafsanjani, and a top aide to current President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad named Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei. The next drama will be the decision of a clerical body called the Guardianship Council about which of the candidates are allowed to run – it has reportedly already ruled that all of the 30 registered female candidates are disqualified by virtue of their gender – and is expected to issue a ruling shortly, though there will likely be a further round of appeals.

First up is Middle East expert Dr. Michael Rubin reacting to the entry of Rafsanjani, and especially the considerable commentary from some pundits suggested he represents a “moderate” candidacy. He notes that this mistake was made when Rafsanjani was elected President for the first time in 1989, and reviews his uncompromising stance and support of major terrorist attacks while in office. Rubin also points to three things to understand about Iranian elections – Iran is not a democracy, one should not overemphasise the importance of the existence of competing factions in Iran, and reformists should not be confused with opposition in Iran. For his important reminder of what the Iranian poll is and is not about, as well as Rafsanjani’s actual record, CLICK HERE.

Next up, Washington Institute Iran expert Mehdi Khalaji looks at the role of the Guardianship Council in approving candidates, in a piece written before the announcement of the candidacy of Rafsanjani and Mashaei. Khalaji predicts that the Council will be very unlikely to approve Mashaei’s candidacy, which has been derided by Khamanei, and also sees signs that the prospects of Rafsanjani being allowed to run are also dubious. Khalaji urges Washington – and by implication all Western governments – to publicly criticise the undemocratic elements of the Iranian electoral process in part as a way to demonstrate the falseness of Iranian propaganda claims that sanctions aim to harm the population as a whole. For Khalaji’s complete analysis, CLICK HERE. Meanwhile, in keeping with Khalaji’s prediction, hardliners are indeed urging the Council to ban both Rafsanjani and Mashaei.

Finally, noted Iran expert Reuel Marc Gerecht takes on at length the many Western pundits who stubbornly insist that, if the West tries hard enough, a grand bargain with Iran can be reached. He reviews the circumstances of the negotiations and why the Iranians have likely turned down already the best offer the West can give, and argues that the diplomatic argument is soon going to turn into enhanced efforts to downplay and blur the terrorist and inherently hostile nature of the Iranian region. Gerecht explores several types of apologists for iran – especially the Iran specialists who have become enchanted with the richness of Iranian culture, and the serious foreign policy types who simply want to let Iran have nuclear weapons out of misplaced “realism” but at unwilling to say so. For this important look at the key to debates going on about Iran in Washington, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Current Iranian President Ahmadinejad faces legal trouble – including up to 74 lashes – over his efforts to support Mashaei.

- The man known as Iran’s “Lech Walesa”, Mansur Osanlu, head of the Tehran bus drivers’ union, has been reportedly driven into exile.

- Two Iranian men allegedly from Iran’s Quds force were recently convicted in Kenya of trying to blow up Western buildings there. Some comment on what this says about the increasingly assertive Quds forces is here.

- Could Syria be Iran’s Vietnam?

- Isi Leibler writes about those who refuse to learn the lessons of the Oslo process experience.

- Or Avi-Guy on what near-legendary investor Warren Buffett has to say about the economic uniqueness of Israel.

Rafsanjani Is No Moderate

Back to Top

————————————————————————

TEHRAN TO DECIDE WHO CAN RUN FOR PRESIDENT

By Mehdi Khalaji

PolicyWatch 2076

May 7, 2013

As the regime narrows the list of approved candidates for the upcoming presidential election, Washington should criticize Tehran for limiting who is permitted to run.

On May 12, Iran’s Guardian Council will begin deliberations on which candidates can participate in the June presidential election, perhaps the most important step in selecting Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s successor. The uncertainty regarding the outcome, coupled with the regime’s repeated claims that nuclear sanctions are intended to hurt the people, gives Washington ample room to criticize the highly controlled electoral process and call for a more open and democratic Iran.

BACKGROUND

To be considered for this year’s election, all presidential aspirants must file by May 11. The Guardian Council — a powerful body with twelve members, six of whom are directly appointed by the Supreme Leader — then decides which candidates are permitted to run based on its subjective judgment of their qualifications. The results of that process will be announced on May 16. Those disqualified can ask the council to reconsider; any such appeals would be decided by May 23.

On June 14, elections will be held for president, municipal council seats, and two vacant seats in the Assembly of Experts, which selects a new Supreme Leader if Ali Khamenei dies. Holding major elections simultaneously helps the regime keep costs down while exploiting the people’s interest in local politics to raise turnout for the presidential vote. Hundreds of thousands of candidates have already registered for the municipal elections; here too, the Guardian Council determines who is qualified to run. Simultaneous elections also decrease the chances of a boycott — reformists and technocrats have applied to run at all levels, so they would have difficulty asking voters to stay home on election day if the Guardian Council disqualifies their presidential candidates but approves their local candidates.

Past presidential elections have frequently produced surprising results, and no one is sure how this one will turn out — at least in terms of which conservative will prevail. If no candidate wins a majority on June 14, a runoff between the top two vote-getters will be held on June 21.

REFORMISTS SIDELINED BUT NOT ELIMINATED

Despite efforts to convince the Islamic Republic’s two previous presidents — seventy-nine-year-old Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and Muhammad Khatami — to enter the race, neither has accepted thus far. In addressing his supporters recently, Khatami asked how one can run for president if he is not even allowed to travel abroad, implicitly referring to himself (he has been barred from leaving the country to participate in international conferences since 2009).

In addition, the regime has heightened its vitriolic rhetoric against both men. In an April 29 editorial by the leading Iranian daily Kayhan, publisher Hossein Shariatmadari, a close confidant of Khamenei, called Khatami a “traitor,” “corrupt on earth,” and “fifth column.” Similarly, Intelligence Minister Haydar Moslehi recently declared, “We have information that the person who claims that he predicted the fitna was himself involved in creating it,” referring to the mass opposition protests of 2009. This was interpreted as a clear warning that neither Rafsanjani nor Khatami should run for president.

Indeed, Ayatollah Khamenei seems bent on not only marginalizing reformists, but also sidelining figures from the first generation of the Islamic Republic. He is unlikely to let Rafsanjani or Khatami run, and all of the other reformist/technocrat candidates are minor figures who have little chance of prevailing in June (e.g., former nuclear negotiator Hassan Rouhani, who is unknown to the vast majority of Iranians despite his high profile abroad). In fact, the Guardian Council may approve such candidates precisely because they are unlikely to garner many votes.

END OF THE ROAD FOR AHMADINEJAD?

In an April 10 editorial in Kayhan, Shariatmadari attacked Ahmadinejad for backing the controversial Esfandiar Rahim Mashai as his favorite candidate (Ahmadinejad himself cannot run because of Iran’s two-term limit). The article pointed out Khamenei’s July 2009 letter to Ahmadinejad criticizing Mashai as an inappropriate choice for vice president, making it difficult to imagine why he would now be considered a viable presidential candidate. Although one Guardian Council member responded to the editorial by stating that no decisions had been made on anyone yet, Mashai has little chance of being approved.

Some Iranian analysts believe that Ahmadinejad is well aware of Mashai’s poor prospects and is pursuing a more subtle agenda — namely, portraying himself as a victim of Khamenei and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. If that tactic succeeds in boosting his faction’s popularity, he would then either introduce another candidate after Mashai’s disqualification or use the momentum to further his own postelection plans. Yet Mashai is probably the only figure in Ahmadinejad’s camp capable of attracting voters, since most Iranians blame the president and his team for years of economic mismanagement, corruption, and international isolation. Accordingly, Khamenei and the Guardian Council’s strategy toward Ahmadinejad’s faction may be the same as their approach to the technocrats and reformists — disqualify or intimidate the main figures while approving the candidacy of minor figures who are unlikely to receive many votes.

NO CONSERVATIVE CONSENSUS

Iran’s hardliners have put forward a great many candidates for the presidential race; in an April 27 speech, Khamenei expressed concern about the number of people vying to run. None of these conservative candidates has emerged as a clear frontrunner, and it is difficult to find any substantial ideological or policy differences between them. Their main strategy centers on blaming Ahmadinejad for Iran’s economic problems, which is a convenient way to minimize the role of international sanctions.

Conservative candidates have also been eager to highlight the president’s penchant for challenging the Supreme Leader’s authority, running a rhetorical race to prove their own loyalty and subservience to Khamenei. Accordingly, the Guardian Council will have difficulty narrowing the field — most of the conservative applicants have served in government, criticized the reformists and technocrats consistently, and advocated the radical version of velayat-e faqih (the doctrine granting the Supreme Leader his authority), so the council has no real justification to disqualify them.

CONCLUSION

Washington should not ignore Iran’s presidential election, particularly given the regime’s repeated claim that U.S. sanctions aim to hurt the people rather than curb the nuclear program. To rebut such rhetoric, Washington should show its concern for the people’s democratic demands.

The U.S. government will have two clear opportunities to react to the election. First, once the final list of approved presidential candidates is announced, Washington should criticize Khamenei for letting the Guardian Council disqualify certain figures and intimidate others into staying out of the race. Second, in the likely event that opposition members inside or outside the country accuse the regime of manipulating the voting process, Washington should express concern about the election’s legitimacy.

Sharp U.S. criticism of the electoral process would pose little risk of hurting the nuclear negotiations, and restraint has proven ineffective in the past — Washington’s relatively muted reaction to the 2009 postelection turmoil failed to improve the regime’s negotiating posture then, so there is little sense in remaining quiet now. In contrast, taking a strong stance against electoral manipulation would show the Iranian people that the target of U.S. pressure is the regime, not them. Supporting their calls for democracy and civil rights is the most effective way to neutralize the government’s anti-American propaganda. Once the election’s trajectory becomes clearer, Washington can turn to the task of assessing how the outcome will affect the nuclear impasse and other crucial issues.

******************************

Mehdi Khalaji is a senior fellow at The Washington Institute.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Radioactive Regime

Iran and its apologists

Reuel Marc Gerecht

Weekly Standard, May 20, 2013, Vol. 18, No. 34

The list is long of Occidentals who’ve fallen for Persia. This isn’t surprising. Compared with Arab lands save Egypt, Iran has a longer history—Hegel described the Persians as “the first Historic people”—and a more layered modern identity. Compared with the Turks, whose indefatigable martial spirit is reified in the unadorned stone power of Istanbul’s magnificent mosques, Iranians are more playful and mercurial. Isfahan’s Sheikh Loftallah Mosque, with its delicate polychrome tiles, its shifting, asymmetrical shapes radiating from the dome’s apex as a peacock, captures brilliantly the Persian love of complexity, synthesis, and whimsy. Its patron, Shah Abbas the Great, a curious, wine-loving, absolute monarch, captured the imagination of contemporary Europeans, including Shakespeare.

Stubbornly attached to their Indo-European language, the people of the Iranian plateau poured their genius into poetry; also art, architecture, and an eclectic blend of faiths, which captivated their Greek, Arab, Turkish, Mongol, and British conquerors. Much like English, which resists and absorbs everything thrown at it, Persian envelops. Before reaching manhood, Ottoman princes were forbidden to learn it—the language of diplomacy and high culture among Muslims throughout much of the medieval and modern periods—since the aesthetic pull and literary range of Persian could lead innocent, Turkish-speaking Sunni boys to Shiism, the faith of the empire’s most dangerous Muslim foe. It’s not surprising that the prophet Muhammad was depicted in human form in medieval Persian miniatures—a “sacrilegious” act that would get an artist jailed, probably executed, in today’s Islamic Republic.

Which brings us to the question: Why do so many foreign-policy types, after 34 years of seeing the revolution in action—seeing Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his successor Ali Khamenei endlessly vent their loathing of the United States in the most sincere religious terms—stubbornly cling to the idea that the Islamic Republic and this country ought to be able to work out their differences? Analysis and policy should be divisible. A thorough examination of Khamenei’s words and actions reveals a tirelessly anti-American, terrorism-addicted Muslim paladin, chosen by divine fate and forged by personal suffering. Nonetheless, many big names in Iran policy still prefer containment of an Iranian nuke to preemption. The Brookings Institution’s Ken Pollack in his soon-to-be published book Unthinkable: Iran, the Bomb, and American Strategy advances a powerful, if ultimately unsatisfying, argument in favor of containment while limning a damning picture of the Islamic Republic. This is rare. Usually, arguments for engagement or containment follow more-fiction-than-fact portraits of the mullahs in power. Are Iran’s many Western apologists analytically challenged, deceitful, or just scared so stiff of another war in the Middle East that they secularize and sanitize the clerical regime?

Washington is now in a self-imposed lull on the Iranian nuclear question, awaiting the Islamic Republic’s presidential election on June 14. We know that this election is meaningless for the atomic program, that Khamenei—not Iran’s president, who will probably be personally approved by the supreme leader before the election—has controlled the nuclear dossier from the beginning. Hassan Rowhani, the former nuclear negotiator, a “moderate,” who openly bragged that Tehran had successfully prolonged negotiations to advance its atomic designs, was clear in his memoirs about who runs the show: Khamenei. The White House understandably wants to avoid the day when the International Atomic Energy Agency issues so damning a report on the Islamic Republic’s advance that the president and his senior advisers are forced to decide whether America preemptively strikes or acquiesces to a bomb in Khamenei’s hands.

A plethora of sanctions are scheduled to take effect on July 1, any or all of which can be waived by the president. The administration is currently trying to stall new sanctions legislation in the Senate. Secretary of State John Kerry wants, congressional sources say, more diplomatic running room, though this go-slow approach, tried before by the Europeans and the Americans, has stopped neither spinning centrifuges nor progress at the plutonium producing heavy-water plant at Arak.

So Many Centrifuges

The West and the Islamic Republic may finally be nearing the denouement of their nuclear standoff. As Tehran gradually replaces its first-generation centrifuges with more efficient models and improves the performance of all its machines, an undetectable “breakout capacity”—the time needed to enrich enough uranium for a bomb to weapons grade—is coming. Probably by mid-2014 the regime will have the ability to convert its 20 percent-enriched uranium to weapons grade too rapidly for the United States to stop it militarily. The Arak facility, meanwhile, which will produce separated plutonium, appears ready to go online by mid-2014. As David Albright, the nonproliferation expert at the Institute for Science and International Security, has tirelessly pointed out, a breakout capacity of three weeks would be almost impossible for Western intelligence, and even the IAEA with its weekly and spot inspections of the Iranian facilities, to detect. And supposing a breakout were detected, it is difficult to imagine Washington’s unwieldy foreign-policy process and cautious president gearing up a preemptive strike within 21 days.

By 2015 the breakout period could well be one week. Olli Heinonen, the former number two at the IAEA and now at Harvard’s Belfer Center, worries that the regime may already have secret storage facilities for enriched uranium. IAEA inspectors privately confess that they don’t know where Iran is building its centrifuges (though they have educated guesses). It’s likely that neither the CIA nor the French foreign-intelligence service, the DGSE, which has been tracking Iran’s nuclear program fairly seriously for decades, has a better idea than the IAEA inspectors. According to a plugged-in French official, France has tried to put centrifuge production on the table at meetings with Tehran. Perhaps still hoping for a serious Iranian offer of bilateral talks with the United States and a deal on 20 percent enrichment, President Obama’s team has so far blocked Paris. But unless the production of centrifuges is somehow slowed and the Arak plutonium plant shuttered, the United States (and Israel) will soon have to choose to preempt or acquiesce.

As we draw nearer to judgment day, those who have assiduously portrayed Iran as nonthreatening—or sufficiently hazard-free to dismiss military action—will surely try to take the foreground. Barack Obama has said unequivocally that he will not allow the Islamic Republic to develop an atomic weapon. He has alluded to the growing menace of a clandestine nuclear dash. “We have a sense,” the president said during the 2012 campaign, “of when they would get breakout capacity, which means that we would not be able to intervene in time to stop their nuclear program, and that clock is ticking.” Democratic doves, Republican isolationists, and bipartisan “realists” may grow increasingly anxious that Obama, who prides himself on his toughness with drones and his long-standing concern about nuclear proliferation, just might mean what he says. It certainly appears that the president’s visit to Israel in March convinced Benjamin Netanyahu that Obama was sufficiently serious to quiet the prime minister’s anxiety about Washington’s intentions. (The extraordinary military and political challenges of an Israeli preemptive strike against the Islamic Republic may also have helped.)

But virtually no one in Washington takes the president’s threat at face value. Does anyone in Tehran? Given Obama’s manifest desire to extricate the United States from Middle Eastern adventures, his caution in Syria, his choice of dovish senior officials, his defense cuts, his parsimony in expressing his willingness to use force abroad, the queasiness of liberals about the legality of preemptive action, and the boldness of the Quds Force, the terrorist unit within the Revolutionary Guard Corps, in planning a bombing run against the Saudi ambassador in Washington in 2011 (the punishment for which was . . . more sanctions), Khamenei is no more concerned about this issue than the American left.

But the supreme leader has shown repeatedly that he has no intention of allowing this American president to punt the problem with honor. The recently concluded nuclear discussions in Almaty, like all previous sessions, failed. And this time round, the Iranians really should have “compromised” if the regime were worried about an American strike. The Americans and Europeans came very close to recognizing an Iranian “right” to enrich uranium to 5 percent. According to both American and European officials, negotiations focused exclusively on 20 percent enrichment, leaving low-enriched uranium off the table. As the Council on Foreign Relations’s Ray Takeyh has commented, American recognition of Tehran’s “right” to enrich uranium to 5 percent would have insulated all of Iran’s enrichment facilities against either American or Israeli preemptive raids. The regime would then have been free to install new centrifuges and swap out old ones and serenely shrink the calendar for an undetectable breakout. Granting Tehran this “right,” which does not exist in the Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which Iran is a signatory, and which violates U.N. Security Council resolution 1696, would also have collapsed international sanctions against dual-use imports—and perhaps fatally weakened the EU sanctions regime, which is already under stress from court challenges. Tehran could have openly purchased all the centrifuge parts it desired, setting an example for other nuke-hungry states.

The Obama administration may not have even realized all of the aftershocks that would follow from an Iranian “right” to enrich to 5 percent. The White House offered Tehran an oil-for-gold deal allowing the Islamic Republic to sell crude in exchange for bullion. According to American and European officials, this arrangement could have been sufficiently lucrative that Washington effectively was offering Tehran a hard-currency lifeline. Whatever coercive utility American and European sanctions have had on the nuclear question would have ceased, since hard-currency reserves keep Iran’s currency from cratering. What’s more, Iran’s ability to pocket Western concessions is probably greater than the West’s ability to rescind them. Foreign gold traders, once fearful of Washington, are again trading more with Tehran. If the Iranian regime had been less ideological (read “religious”) and more pragmatic, it could have aggressively used the gold loophole to gut the most crippling financial sanctions and possibly fracture the trans-atlantic alliance against it.

It’s unimaginable now that Washington could offer more than it did in Almaty. There simply are limits to how forthcoming the White House can be in its willingness to let the Iranian regime go nuclear; past presidential rhetoric cannot be wished away. Nor can North Korean nuclear nuttiness, which underscores the scariness of third-world rogue states’ having atomic weapons. Pyongyang has been essential to the development of Iran’s ballistic missiles and probably critical to its nuclear quest. The North Koreans helped build an undeclared, weapons-capable, nuclear fuel plant in Syria, which the Israelis destroyed in 2007; it’s likely that Iran backed, if not initiated, the North Korean-Syrian deal, as a means to further its own nuclearization. Ironically, North Korean behavior has now made the Islamic Republic’s pursuit of the bomb more problematic.

Khamenei’s and Kim Jong-un’s resolute defiance of the West has put Obama into a pickle that could, conceivably, oblige the president to strike. It will become increasingly difficult to ignore the enormous centrifuge buildup and the progress at Arak. Although the president likes to highlight an Iranian decision to weaponize as the immovable red line, knowledgeable senior administration officials say privately that American intelligence can only reliably monitor—thanks to the IAEA inspection system—uranium enrichment and plutonium processing. Human sources and intercepts, Washington’s only means of monitoring Iranian “intentions,” have been depressingly inadequate. The CIA, need we recall, missed the nuclear weaponization of every nonallied state—the USSR, Communist China, South Africa, India, Pakistan, and North Korea—and probably didn’t guess well with Israel. On Iran, the National Intelligence Estimates, especially the much-disputed 2007 assessment which claimed that nuclear weaponization had stopped after the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, show, in their sliding scale of equivocation and assertion, the gaping holes in Washington’s information on the Islamic Republic’s nuclear establishment. Any active-duty or former senior official who suggests that American intelligence can successfully monitor Iranian intentions—for example, the director of national intelligence, James Clapper, or former ambassador Thomas Pickering, who has made Iran engagement a personal hobby—is fibbing, to himself and to others.

As the Israelis and the French have always contended, enrichment and plutonium processing are the de facto benchmarks for weaponization. If the Israelis have any intention of striking the Islamic Republic’s nuclear sites, they will have to do so before the increasing number of advanced centrifuges makes such an action ineffectual and too dangerous. It is probably already too late for a raid—certainly in Europe and Washington there is palpably less fear of Israeli preemption since the Islamic Republic’s progress on centrifuges and the limitations of Israeli airpower have become more apparent. If Jerusalem is still serious about striking and the White House knows the Israeli cabinet has decided to take the risk, it’s possible the president will actually prefer to see Jerusalem preempt, knowing that an angry Iranian response could oblige Washington to defend its interests in the region. An American raid on Iran first could be too difficult for Obama to swallow; finishing off the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program after the Israelis had struck would be politically and spiritually much easier. In any case, as fear of an Israeli strike diminishes—and, as a result, European and American unity against Tehran frays—the American discussion of preemption will grow more serious.

The savvy parts of the antiwar American left can see the writing on the wall. The Ploughshares Fund, a leading funder of nonproliferation projects, is already shifting its focus to containment. And for the left, “containment” means a nonaggressive policy toward the Islamic Republic (the bloody reality of Cold War containment being long forgotten). Obama’s legendary caution and deep discomfort with the use of American power abroad may not be enough to overcome the logic and responsibility of the presidency, where risks to national security are difficult to downplay. Obama’s pledge to stop an Iranian nuke may have initially been bluff. But presidential bellicosity, as George W. Bush learned, has more to do with supervening events than with a president’s preexisting proclivities. If the president doesn’t punt on Syria, where Bashar al-Assad appears to have crossed the White House’s red line on using poison gas, then the odds that Obama isn’t bluffing about an Iranian nuke go up. (The reverse is also true.) And even if the president doesn’t manfully follow through in the Levant, Iran still may be a special case. The strategic magnitude of Khamenei’s having a nuke is so great that even “caution” in Syria might not imply American timidity with the Islamic Republic.

So the struggle among those who want to acquiesce to an Iranian bomb and withdraw from the Middle East, those who want to acquiesce but try to contain Tehran, and those who want to preempt will soon begin in earnest. Although Khamenei and his Revolutionary Guards may make it difficult to minimize the menace of a nuclear-armed Islamic Republic, we can expect to see many attempts to downplay the clerical regime’s fusion of faith and ideology. As with Iraq in 1990 and 2003, the closer we come to war, the more energetic will be the efforts to blur in shades of gray the history and nature of the foe. The rich complexity and contradictions of Iranian society will aid those who just want to let Khamenei and his guards have their weapon.

The Apologists

Those who will excuse the regime are not all intellectually flippant—Flynt and Hillary Leverett and Trita Parsi come to mind. Nor are they Iranian-Americans like the writer and Charlie Rose favorite Hooman Majd and the Rutgers academic-turned-Iranian presidential candidate Hooshang Amirahmadi who play and proselytize among the two countries’ progressive elites, always trying to keep the door open to the beloved Old World. Nor are they in general folks who are profoundly uncomfortable with American power. They aren’t, for the most part, those who reflexively give the moral high ground to third-worlders jousting with the West. Many of this hopeful set are accomplished, even hard-nosed, diplomats, soldiers, scholars, journalists, and pundits who appear to believe that a bargain is still possible between the United States and the Islamic Republic.

The Iranian regime’s love affair with violence—no state, with the possible exception of Syria under the Assads, has so actively promoted terrorism—usually makes small ripples in these folks’ assessments. The theocracy’s penchant for what the military historian David Crist calls “covert war” is regularly depicted by the hopeful as the defensive reaction of an insecure regime, as if the supreme leader and his Revolutionary Guards were in need of psychiatric help. But Tehran embraces terrorism. Not even the former Soviet Union, with its affection for hard-left revolutionary groups and the Palestine Liberation Organization, aided anti-Western terrorist organizations as energetically as the Islamic Republic. This the apologists see as realpolitik. Even Tehran’s flirtation with the Sunni killer elite—the Egyptian Islamic Jihad organization of Ayman al Zawahiri and al Qaeda (see the 9/11 Commission Report and more recent Treasury designations)—is seldom brought up. Tehran’s fondness for creating Hezbollahs (“Parties of God”) wherever it has the reach and can find the local talent usually gets misconstrued as bad-boy Shiite solidarity around local grievances rather than a manifestation of Iran’s transnational revolutionary ideology. The regime’s exuberant embrace of anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial (that is, Holocaust approval) gets downplayed as an annoying subset of the Israeli-Palestinian confrontation.

Khamenei’s crackdown on the pro-democracy Green Movement in the summer of 2009 led to thousands jailed and tortured and, according to credible Iranian sources, around 150 killed; it also turned the ruling elite against itself. Yet even this only dented the diplomacy-is-possible mindset, which sees Iran’s internal affairs as largely extraneous to whether the United States and the Islamic Republic can achieve anything like normal relations. The supreme leader damned the millions who hit the streets as agents of America. They weren’t: Even under Ronald Reagan, who used covert action more than his successors, America never had a regime change policy for the mullahs or even soft-power, pro-democracy operations that went beyond nostalgia-tweaking, in-country TV broadcasts and the publishing of Persian editions of liberal books.

Khamenei, obsessed since youth with the insidious, sensual attraction of the West, sincerely believes the gravamen he hurled at the Green Movement. Yet three-and-a-half years later, we still find serious people writing op-eds, policy papers, and books reflecting on “mutual mistrust,” “mutual demonization,” “years of suspicion,” and the “American missteps” that have kept the clerical regime and U.S. presidents from realizing the “obvious” geostrategic interests their countries share.

These apologists don’t persevere for the money, often the reason adults in the West, especially in Washington, say exculpatory things about foreign tyrannies—even if Tehran does bankroll a few think-tankers and university scholars through private “cut-out” philanthropy (the Alavi Foundation in New York, pursued by federal prosecutors in 2009, is a case in point). And the Islamic Republic certainly isn’t Saudi Arabia. There’s not a soul in Washington or New York or London who would defend the sybaritic Saudi royals and their head-and-hand-chopping Wahhabi clergy were it not for cash. Without oil, Saudis would have the same appeal as the Afghan Taliban.

In the past, before the Islamic Republic’s less radical set around former president Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) got stuffed, American corporate money could encourage a sympathetic disposition towards Tehran. A prestigious American think tank could organize a major study that supported expanding U.S.-Iranian commerce, and innocently have a principal organizer and drafter of the study make calls from her Exxon office. Former ambassador Pickering, a senior vice president at Boeing from 2001 to 2006, has urged the United States to keep trying to normalize relations with the Islamic Republic. Pickering, however, rarely acknowledges his Boeing link in op-eds and articles, even though the company was, until recently, a big fan of lifting sanctions so as to sell airplanes and parts to an eager Persian clientele. Take away Boeing, and Ambassador Pickering would surely have had the same views toward the Islamic Republic. But the unacknowledged overlap is disconcerting.

The Cultural Apologists

Part of the reason so many Americans and Europeans have been charitably disposed towards the Iranian regime is cultural spillover. The magnificence of the Persian past and the warmth of the Iranian people still attract. Western journalists and scholars who have been given permission to travel in Iran (the list keeps shrinking) are particularly susceptible. The International Herald Tribune and New York Times columnist Roger Cohen, who visited the Islamic Republic before the crackdown in the summer of 2009 and wrote pieces extolling the tolerant, hospitable side of the Iranian character, is an eloquent example of this cultural critique among aesthetically sensitive Westerners. Cohen extended his analysis even to Persian Jews, who’ve emigrated and fled in large numbers since the revolution and whose leadership can get hit hard when the regime feels angry (with charges of espionage, for example, or sodomy, a capital offense). Time in Iran led Cohen to write, “The reality of Iranian civility toward the Jews tells us more about Iran—its sophistication and culture—than all the inflammatory rhetoric. This may be because I’m a Jew and have seldom been treated with such consistent warmth as in Iran.”

Cohen had a point, which he did not make: Shiite Iranians have been tortured and killed far more frequently than Jewish Iranians since Shiites are expected to embrace fully the Islamic Republic’s mission civilisatrice at home and abroad; religious minorities are not. Jews in Iran, if they keep silent about Israel and show public fidelity to the Islamic order, are “museum pieces,” a part of Persian history that revolutionary mullahs tolerate but rarely esteem.

Cohen’s commendable appreciation of Persian culture and history led him to the British Museum to see Cyrus the Great’s Cylinder, the cuneiform-on-baked-clay legal guide and panegyric, with its timeless message of “tolerance.” The cylinder is coming soon to the Smithsonian, an event, Cohen noted, that “occurs with the United States and Iran still locked in the negative stereotypes the movie Argo has done nothing to assuage. . . . But compact and mute, . . . [the cylinder] is a powerful antidote to the belligerent certitudes and shrieking ‘truths’—an object packed with ambiguity and now freighted with a 2,500-year-old tale of human vanity and frailty.” One would think that Cyrus’s legendary magnanimity, which led to the Jews’ return to Israel from their Babylonian captivity and the reconstruction of the Temple, would be more usefully displayed in Tehran than in Washington.

A variation of this cultural critique of politics is offered by John Limbert, the former hostage, who is probably the most erudite Persian-speaker ever to pass through Foggy Bottom. Limbert had retired from the State Department to teach at the Naval Academy, but returned to Washington in the service of one he saw as a possible breakthrough president, promising to reset relations with the Muslim world. It was likely Limbert who drafted the Persian language letters from President Obama to Khamenei in 2009. Soft-spoken, considerate, with a deep and wry grasp of Persian literature, Harvard-educated, and married to an Iranian, Limbert was widely welcomed among the cognoscenti in Washington, who shared his hopes. After the pro-democracy Green Movement erupted and was suppressed, catching the White House off guard, Limbert went back to teaching. “The Obama administration has been in office now for over a year and a half, and I think everyone thought we would be in a better place with Iran,” he forlornly remarked. “Not necessarily that we would be friends, but that we would at least be talking to each other on a regular and civil basis.”

Limbert has written and spoken trenchantly about the Islamic Republic’s failures. But his sympathy for the Iranian people and his displeasure at seeing Washington, even under Obama, incapable of the nuanced approach he believes required for such a complicated country reinforces a mindset Limbert has probably had ever since the hostage-takers blindfolded him and the other Americans at the Tehran embassy in 1979: two countries misunderstood, errant, unnecessarily demonizing each other, locked in a Manichean struggle. But for Limbert, as for many cultural apologists, the greater burden rests with America, the superpower, which helped engineer a regrettable coup d’état in Iran in 1953 and later did little to curb the shah’s tyranny.

Other culture-first observers of Iran try to translate personal experience into larger political points. The English journalist Christopher de Bellaigue, whose finely etched portraits of Iranian life often appear in the New York Review of Books, is perhaps the best of these. He conveys the mirth, passions, cynicism, and religious and economic fatigue of contemporary life in an Iran transformed by the revolution. His writings are a counterpoint to those of expatriate Iranians and Westerners who see counterrevolution just around the corner. In Bellaigue’s telling, Persians may live in a theocratic state that is capable of brutality, but its harshness is softened by a still-powerful traditional culture and an open love of modernity. Bellaigue sees an Islamic Republic where the regime has some legitimacy among the faithful (he’s undoubtedly right), but is weakened by pervasive cynicism.

The Shiite love of taqiyya, the deception that believers may legitimately use against nonbelievers or, as was most often the case, more powerful Sunnis, now plays against the mullahs and their security services. The regime constantly lies, especially about corruption among the revolutionary elite; the Iranian people lie right back. Bellaigue, also married to an Iranian, always sees the kaleidoscope of color—the humanity—that exists even within the regime. He unfailingly empathizes, fulfilling the imperative that any foreigner see the natives as they see themselves. Seven years ago, when the Western commentariat feared that George W. Bush might unleash another war, Bellaigue frightfully envisioned an American attack during a languid Iranian summer. “In my heart, I am more like the people about me. ‘Crisis? What Crisis?’ As the air warms and my wife lumbers into her final smiling month of pregnancy, it seems too vile to imagine that sometime soon, a nice American boy may press a button or open a chamber and rain destruction down around us.”

The contradictions of the Islamic Republic can have a profound effect on Westerners looking in. The closer you get, the more disorienting they become. In America, as in Western Europe, there is no great disconnect between culture and politics: The morality of the average American is roughly in tune with the mores of his elected representatives. Even in France, where the political elite, refined by Parisian tastes and generations of meritocratic education, is the most distant from the governed, there is still a shared moral compass that defines and limits the actions of the political class. In Iran, as in most authoritarian societies, the goodness of the people seems outlandishly at odds with the distant wickedness of the ruling thugs. Limbert’s admirable little book on the Islamic Republic, written in 1987, captures this disconnect in its title, Iran: At War with History. The constant incongruities—the unrelentingly wry, cynical, playful genius of Iranians versus the harsh Islam of the Khomeinists—is compounded by the long-standing democratic aspirations of so many Persians, which have been advanced by even culturally conservative clerics. One doesn’t have to accept the Iran-centric cultural critique of the Stanford scholar Abbas Milani (Iranians had the cultural building blocks for an open democratic society before most Europeans did) to nonetheless embrace Milani’s enthusiasm for la différence persane. Iranians aren’t Arabs, Uzbeks, Turkomans, or Pakistanis: There is something in Persian culture, something old but effervescent, prideful and curious, that makes the observer immediately conscious of unfulfilled, enormous potential, of unrequited but not unreasonable dreams.

Attentive Western observers cannot fail to notice the powerful oblique criticism of the regime in contemporary Persian literature and film. Though tolerance for these scathing critiques has ebbed and flowed since Khomeini’s death in 1989, the general effect of such colorful dissent is to underscore how different Iran’s religious dictatorship is from lifeless Communist tyrannies, Saddam’s Iraq, or even the more humdrum secular authoritarianism that the Great Arab Revolt has challenged since 2010. Truly wicked regimes—the type that really shouldn’t have nuclear weapons—wouldn’t allow such dissent, the Western commentariat suggests. Occidentals need consistency, and Iranians don’t supply it. If the hypocrisies of Persian society are so omnipresent and impressive—especially at the top of society (clerics indulging in sexual escapades, the sons and daughters of the rich and powerful at play in London, Paris, and Rome)—then nothing in Iran can really be that holy. The regime, nasty as it may be, just isn’t sufficiently hard-core and competent to terrify the West, even if the regime gets a nuclear weapon.

Since the end of the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88), which finally stopped young Iranian men from martyring themselves, Westerners have not been powerfully exposed to the passion play side of the Iranian character that latched onto Shiism, the martyr’s faith par excellence. The Irano-Semitic taste for myth can make the Persian faithful highly susceptible to idealistic visions and hidden truths. Marry that to Persian hubris and to a nasty modern embitterment that is religious, ethnic, and profoundly Marxist, and one can see why Iran had an Islamic revolution and the pitiless, obsidian-eyed Ruhollah Khomeini became the Imam, a charismatic leader touched by God.

The dark side has always been politically preeminent in the Islamic Republic, even after the war against Saddam Hussein had largely burned jihadism out of the common faithful. Even in the early 1990s, when Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the “pragmatic” major domo of the politicized clergy, was opening Iran to European investment and trying to find ways to attract American capital and technology, Rafsanjani and Khamenei, working amicably in tandem, were blowing up Jews in Argentina and Americans at Khobar Towers and murdering Iranian dissidents across Europe. In 1997, when the always-smiling Mohammad Khatami won nearly 70 percent of the popular vote for president, most Western academics and journalists who covered Iran saw Thermidor coming. They believed their Iranian interlocutors, highly Westernized reformers, proud but dispirited revolutionaries all, who were hopeful that the Islamic Republic would have a soft evolution to popular sovereignty. They badly misjudged Khamenei, who loathed Khatami’s “dialogue among civilizations”; they didn’t know at all the Revolutionary Guards who’d risen to manhood in the war and remained, even after the slaughter, committed to Khomeini’s dreams. The fraternity of combat and their own miraculous survival made these warriors an elite, with a hardened sense of divine destiny and entitlement.

Today, visiting journalists and academics, like Western nuclear negotiators, rarely spend time with the overseers of Evin Prison, who can beat, rape, and torture. Nor do they hang out with the dissident-beating Basij or chat with active-duty intelligence officers who have learned how to crack Iranian families apart through just the intimation of violence. They seldom converse with the hard-core clergy, who still recognize Khamenei’s right to rule, or with the mullahs-in-the-making at the Revolutionary Guard Corps’s new clerical school in Qom. Resident or visiting Westerners have little to no firsthand knowledge of senior guardsmen, especially the Quds Force, responsible for recent lethal strikes on Israeli diplomats and tourists and the targeted killings of American soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Quds Force has assumed liaison responsibility from Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence for foreign radical Islamic groups and terrorist organizations. This assumption of authority mirrors the enormous growth in power of Khamenei’s personal office, which now employs upwards of 5,000 people, and his strong preference for the Revolutionary Guards over other state institutions. The nuclear program is under the corps’s supervision. It is not unreasonable to guess that Khamenei would give the Quds Force, his most trusted praetorians, control of the Islamic Republic’s atomic weapons.

Cultural apologists, who tend to be thoroughly secular, don’t highlight the unbeliever-vs.-God dimension to the Islamic Republic’s internal and external struggles. Modern radical Islamic militancy comes in many shades, but it is often fairly forgiving of believers’ personal faults so long as they have the big vision correct. This derives from traditional Islam, where heresy is an awkward, undigested concept in large part because Islamic theology is so thin (the Holy Law, at least in theory, is what counts) and the “confession of faith,” the shahada, the essential and sufficient acts for a Muslim, are so few. Sunni and Shiite fundamentalists certainly want the believer to follow a code of conduct (no booze, no pork, prayer, sex only with one’s wives or husband), but the real issue for Islamists is the struggle between the West (at home and abroad) and the faith. It is overtly political, yet also, in their minds, explicitly religious.

The omnipresent hypocrisies of the revolutionary elite don’t really touch their faith since religion in the Islamic Republic has become “secularized.” There is the political creed, which is primary, and then there is personal faith, which is between you and the Almighty. The same secularizing process is now happening to the empowered Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Westerners, with their Christian roots, have an extraordinarily hard time digesting the obviously irreligious political maneuvering and corruption of sincere, deadly serious Islamists. Westerners see contradictions and smell pragmatism; radical Muslims see right through the contradictions to the categorical imperative: hatred of the United States, Jews, and Israel (the order may vary, but all three are always there). Whether Rafsanjani’s, Khamenei’s, and senior guard commanders’ children are partying hard in London tells you little about their parents’ conception of Islam or tolerance for Western culture (and little about the children’s commitment to their parents’ creed). It tells you nothing about why the revolutionary elite has so consistently used terrorism as both statecraft and soulcraft. VIP hypocrisies are a digression from the fundamental observation made by the Wall Street Journal’s Bret Stephens: Mullahs who can’t make up their minds whether it’s lawful to bash a woman’s head in for having sex outside wedlock ought not to have access to a nuclear weapon.

The Diplomatic Apologists

The analytical missteps of the cultural apologists set the stage for policy types in Washington who just want to let Tehran have the bomb but are unwilling to say so. Many of the VIP signers of the reports of the Iran Project, which have been hailed and partly paid for by the Ploughshares Fund, would come under this rubric. The Washington foreign-policy establishment always has a zeitgeist, and on the Iranian nuclear question the considered, socially acceptable position is that diplomacy and sanctions still have time to work—but, as the president has it, “all options are still on the table.”

Most foreign-policy cognoscenti have already acquiesced to the idea, if not yet the reality, of nuclear weapons in the hands of Khamenei and his praetorians, but they don’t want to gainsay the president publicly—or let go of the diplomatic option for fear that the president might be obliged to launch a preemptive strike.

Though dimmed in our memories, 9/11 still has a kick. It’s difficult for former senior officials (less so academics) to say openly that it would be better to let terrorists have an atomic bomb than risk war between the United States and the Islamic Republic. So they prevaricate and try to lessen the mullahs’ menace. And some, like former ambassadors Pickering, Frank Wisner, Daniel Kurtzer, and William Luers and the MIT professor Jim Walsh, who have all striven to advance mini-“grand bargains” and nuclear compromises, may well believe what they write about Iran. At a recent McCain Institute debate on the Islamic Republic, Pickering averred that Washington and Tehran are now closer to a diplomatic resolution of the nuclear imbroglio than they have been in years. This would be news to the French, who have the finest diplomatic service in the West and have been doggedly negotiating with Tehran over its nuclear program since 2003 and engaging the regime, at times with great enthusiasm, since 1992.

At the McCain Institute debate, Pickering complimented the president for keeping open the possibility of preemption since it enhances American diplomacy. Yet in late 2012 he called “all options on the table” a “gold-standard trope” of Republican jingoists, and in 2008 in the New York Review of Books he called it “unrealistic” and “dangerous.” The unacknowledged logic is: If preemption is off the table, then any diplomatic track is acceptable since there is ultimately no irreconcilable point of contention. If one could somehow talk the Iranian regime into building only 500 IR-2 centrifuges in six months instead of 1,000, then Western diplomats could claim they’d succeeded. With this crowd, diplomacy is really not about prevention. So why not recognize the regime’s “legitimate” right to 5 percent enriched uranium? With Persian pride thus satisfied, so the hope goes, the Iranians might voluntarily slow their program. Once Washington has sensitively dealt with Iran’s “enduring sense of insecurity” and shown a willingness to rise above 34 years of “mutual ignorance” and “overpowering distrust” and bridge “the vast cavern of psychological space” between it and the mullahs and their guards, then self-interest should lead the Iranian regime, in today’s “increasingly geo-commercial era,” to seek a more prosperous normalcy with America.

It’s probably the most amusing irony to be found within the American foreign-policy establishment: The more merry realists and soft-hearted liberals advocate a friendlier American approach to the Islamic Republic, the more they amplify, if that’s possible, the supreme leader’s hatred of the United States. Anything that brings America closer, that threatens to bring normalcy to U.S.-Iranian relations, is anathema to him. A grand bargain for Khamenei is death. Mini-grand bargains are slow-motion suicide. Barack Obama was the test case. American and European Iran apologists could not have asked for a more promising president to test their theories. In 2009 Obama actually believed that mutual ignorance and, at least on the Iranian side, justified distrust had defined bilateral relations before his coming. He extended his hand. He dreamed of direct, unconditional U.S.-Iranian talks. He kept quiet when the Green Revolution erupted on Tehran’s streets. Obama was certainly prepared in 2009—if Khamenei had only given him an encouraging sign—to waive the then largely ineffective U.S. sanctions against the Islamic Republic. There was no “missed opportunity” with this president. How did Khamenei respond to Obama’s entreaties? He called America shaytan-e mojassem (“Satan incarnate”).

The increasing number of Iranian centrifuges and extent of plutonium processing at Arak will surely bring much-needed clarity and honesty to Washington’s great Iran debate. The choices before us are preemption, aggressive containment, and retreat. And effective containment, which would strike back militarily against Iranian-directed or -inspired terrorism, could lead to war—with a nuclear-armed Islamic Republic. So we will soon see whether the indomitable late French intellectual and official Thérèse Delpech, who’d closely watched France’s and Europe’s dealings with Islamic Republic, was right. An admirer of the United States, she was nevertheless skeptical that almighty Washington would do any better than the less mighty Europeans had with the Islamic Republic. In her 2007 book Le Grand Perturbateur (The Great Agitator), she reflects on the nature of the clerical regime and the ups and mostly downs of European-Iranian relations. Looking at a bleak future, Delpech wryly closes with this insight: L’expérience est une école où les leçons coûtent cher, mais c’est la seule où même les imbéciles peuvent apprendre quelque chose. (“Experience is a school where the lessons cost dearly, but it’s the only place where even imbeciles can learn something.”)

Even after 9/11, it’s possible that Delpech will prove to have been too optimistic.

Reuel Marc Gerecht, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a former Iranian targets officer in the CIA’s clandestine service, is a contributing editor at The Weekly Standard.

Tags: Iran