Protests in Baghdad throw administration’s Iraq plan into doubt

By Greg Jaffe

Washington Post, April 30

President Obama’s plan for fighting the Islamic State is predicated on having a credible and effective Iraqi ally on the ground in Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi.

And in recent days, the administration had been optimistic, despite the growing political unrest in Baghdad, about that critical partnership.

But that optimism — along with the administration’s strategy for battling the Islamic State in Iraq — was thrown into severe doubt after protesters stormed Iraq’s parliament on Saturday and a state of emergency was declared in Baghdad. The big question for White House officials is what happens if Abadi — a critical linchpin in the fight against the Islamic State — does not survive the turmoil that has swept over the Iraqi capital.

The chaos in Baghdad comes just after a visit by Vice President Biden that was intended to help calm the political unrest and keep the battle against the Islamic State on track.

As Biden’s plane was approaching Baghdad on Thursday, a senior administration official described the vice president’s visit — which was shrouded in secrecy prior to his arrival — as a “symbol of how much faith we have in Prime Minister Abadi.”

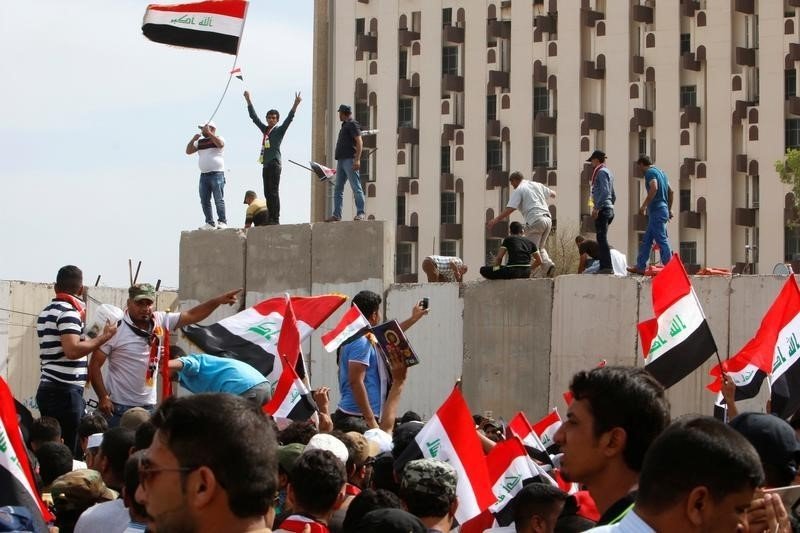

Photos from the scene as protesters storm the Iraq parliament in Baghdad

Demonstrators climbed over blast walls surrounding Baghdad’s highly fortified Green Zone and could be seen streaming into the parliament building.

After 10 hours on the ground in Baghdad and Irbil, Biden was hurtling toward his next stop in Rome. The feeling among the vice president and his advisers was that Iraqi politics were on a trajectory to greater calm and that the battle against the Islamic State would continue to accelerate. Some hopeful advisers on Biden’s plane even suggested that Abadi might emerge from the political crisis stronger for having survived it.

No one is talking that way now. “There’s a realization that the government, as it’s currently structured, can’t hold,” said Doug Ollivant, a former military planner in Baghdad and senior fellow at the New America Foundation. “It’s just not clear how the Iraqis get out of this. I just don’t see how they will.”

It is equally unclear how the administration will move forward if Abadi is unable to consolidate his tenuous grip on power. For much of the past year, the Iraqi prime minister’s survival was taken as a given by senior White House officials who were far more focused on the military fight against the Islamic State.

The president and his top aides have pointed to battlefield gains against the group in Iraq as proof that the administration’s much-criticized strategy was working. In the past 18 months, the Islamic State has lost more than 40 percent of its territory in Iraq, according to U.S. officials.

Attacks on the group’s banks in Mosul have blown up cash totaling from $300 million to

$800 million, according to Pentagon estimates.

“Militarily, the momentum is clearly in the coalition’s favor against [the Islamic State],” said a senior administration official traveling with Biden to Baghdad who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the White House’s strategy. “Every objective fact speaks to the fact that [the Islamic State] is losing.”

Obama has sought to accelerate the military campaign by sending more than 200 U.S. military advisers to Iraq and giving commanders authority to use lethal Apache attack helicopters in support of Iraqi forces. In a recent interview, the president said that by the end of the year he expected that the United States and its Iraqi partners will have “created the conditions whereby Mosul will eventually fall.”

Another senior administration official said that U.S. counterterrorism efforts “always benefit from a stable partner on the ground” and that the Abadi government continues to have the administration’s full support. Even with the current instability in Baghdad, the campaign against the Islamic State will continue, said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive counterterrorism operations.

The political crisis in Baghdad began when Abadi made a bold push to replace politically connected members of his cabinet with technocrats and reformers. The prime minister said that his moves were intended to stamp out corruption.

But the proposals alienated powerful blocs and provoked raucous debates within the Iraqi parliament. Thousands of protesters threatened to storm the heavily fortified Green Zone, which is the seat of Iraqi power, but then seemed to back off in the days before Biden’s arrival.

Biden’s meetings Thursday with Abadi and other senior Iraqi officials focused primarily on making sure that the political strife in Baghdad was not interfering with military preparations to retake Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, from the Islamic State.

“We talked about the plans that are in store for Mosul and the coordination that’s going on with all of our friends here,” Biden told reporters after his meeting with the Iraqi prime minister. “And so, I’m very optimistic.”

As he spoke, the vice president was standing next to Salim al-Jubouri, the Iraqi parliament speaker. He pointed to Jubouri and noted that they last talked in Biden’s office in Washington. “This is an old friend,” Biden said.

Less than 36 hours later, the protesters were dancing and stomping on Jubouri’s desk in front of the parliament chamber. Jubouri had fled the building.

The dramatic turn of events, some analysts said, points to the critical flaw in the Obama administration’s approach to the battle against the Islamic State, which has prioritized defeating the militant group over the much tougher task of helping Abadi repair Iraq’s corrupt and largely ineffective government.

“The message to the Iraqis has been to focus on the short-term problem that this president would like solved by January,” Ollivant said. “The focus is on the symptom and not the root cause of the problem.”

Other analysts said that the Obama administration’s campaign against the Islamic State was, from the outset, too dependent on Abadi, a weak prime minister who is trying to survive in a political system overrun by cronyism and competing sects.

“We get seized with individual personalities,” said Ali Khedery, who served as special assistant to five U.S. ambassadors in Baghdad from 2003 to 2009. “We fall in love with them. I agree that Abadi is generally speaking a good ally of the United States, but there isn’t much under his control.”

Because Iraqi society is so fractured along ethnic and sectarian lines, Khedery said the U.S. administration should adopt a more decentralized approach, working directly with individual Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish leaders. “What you have is a society that is deeply polarized between communities and even polarized within those communities,” Khedery said. “We need a radical new formula.”

There is no indication at the moment that the White House is considering such a radical change in approach. For now, the hope is that the current unrest in Baghdad is just a blip. The protests were sparked by Shiite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, who is now under pressure from Iran and his fellow Shiites to rein in the demonstrations, said a senior U.S. official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal Iraqi politics.

“Maybe [Sadr] will realize he took a step too far and will dial it back,” the official said. “That could give Abadi more space.”

It is also possible that the protests, spurred by the Iraqi government’s failure to provide basic services such as clean water and electricity, could grow worse. This time, demonstrators broke chairs and smashed windows in the parliament building. They berated lawmakers and chanted slogans for TV cameras.

“Iraq is becoming increasingly ungovernable,” said Emma Sky, who served as a senior political adviser to the U.S. military prior to the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011. “Non-state actors are stronger than the state. The government is paralyzed and corrupt.”

Greg Jaffe covers the White House for The Washington Post, where he has been since March 2009.

BACK TO TOP