UPDATES

A misleading and flawed poll sparks “apartheid” claims

October 26, 2012 | Sharyn Mittelman

This week Gideon Levy of Haaretz published an article on the results of a very misleading and flawed poll with the title “Survey: Most Israeli Jews would support apartheid regime in Israel” on October 24. Levy’s report was accompanied by an opinion piece entitled, “Apartheid without shame or guilt: That’s just the way we are.”

As a result of the Haaretz publicity, false reports that Israeli Jews support apartheid, made damaging headlines around the world, including in Australia, where Ruth Pollard’s articles titled “Jewish Israelis favour discrimination: poll” was published in the Age and “Poll finds Jewish Israeli support for segregation” in the Sydney Morning Herald on October 25. Pollard’s coverage failed to include any significant reactions, critiques or analysis from mainstream Israeli sources.

The headlines were concerning, but once people were able to access the polling data (which was not linked to the Levy or Pollard article), it became clear that not only was the poll’s methodology questionable, but the analysis being presented of the poll data was both distorted and politically skewed.

The poll conducted by Dialog, was organised by the Yisraela Goldblum Fund, which appears to have an agenda for promoting the notion of ‘apartheid’ in Israel. Even the New Israel Fund, which admits to having undertaken joint projects with the Yisraela Goldblum Fund, denied any association with the poll. In fact, Deputy Communication Director for the New Israel Fund, Noam Shelef, wrote a strong critique of the poll and Levy’s analysis in the Daily Beast:

“I admire Gideon Levy. He’s had the courage over the years to document some of the ugliest aspects of the occupation. But the manner in which his column presented the information – under the headline ‘Most Israeli Jews would support apartheid regime in Israel’ – seems to amount to a misrepresentation of the data.”

In addition, the poll only surveyed 503 people, which appears problematic given that Israel has a Jewish population near 6 million, and widely diverse groups of people with divergent views.

Issues raised by the poll and analysis:

Apartheid?

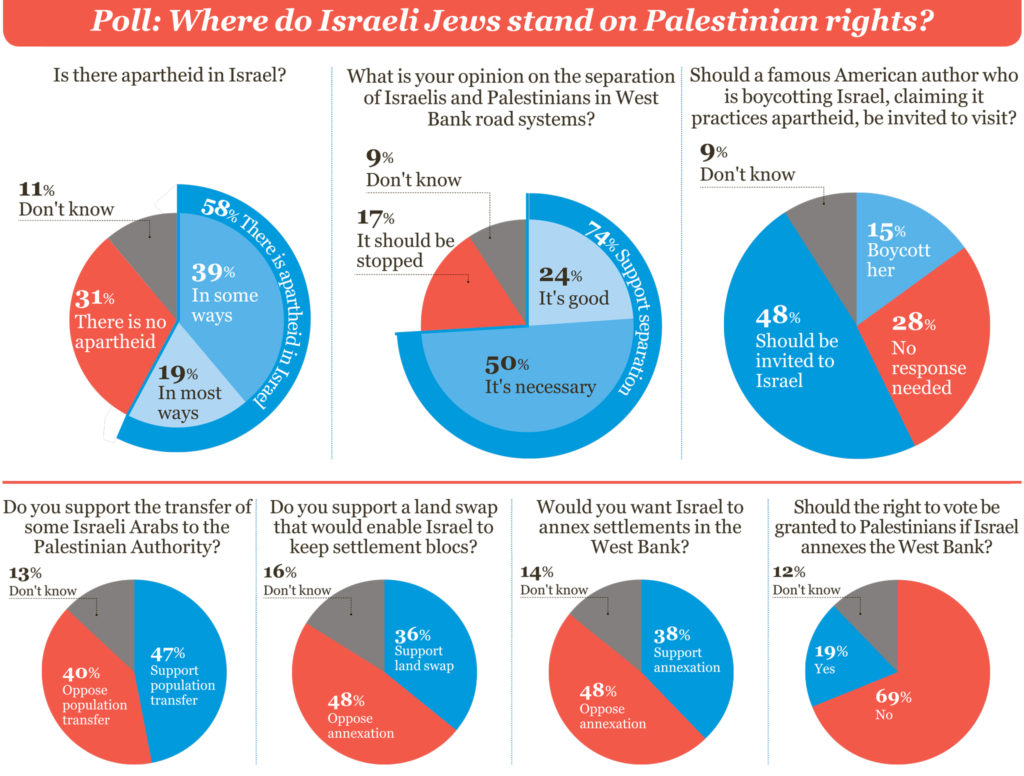

On the issue of Israeli Jews’ alleged ‘support’ for apartheid, Levy writes, “most of the Jewish public (58 percent) already believes Israel practices apartheid against Arabs. Only 31 percent think such a system is not in force here.”

Actually the poll asked, “Regarding the American author’s claim that there is apartheid in Israel, which of the following opinions is closest to your opinion?” to which only 19 percent said that there was apartheid “in a lot of fields”, and 39 percent “in a few ways”. However, the answers received are meaningless since the question failed to provide a legal definition of ‘apartheid’ – often defined as acts “committed in the context of institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination by one racial group over any other racial group or groups and committed with the intention of maintaining that regime”. Even Levy admits in Haaretz the survey conductors said that the term ‘apartheid’ “was not clear enough to some interviewees”.

This confused messaging is also evidenced in the title of the survey which when translated reads: “Results of a survey poll regarding equality and apartheid (desire to separate)”, suggesting that it defined apartheid not as a system of instititionalised state racism, but as a “desire to separate”. Therefore, respondents may have felt they were being asked about discrimination, and/or separatism as opposed to “apartheid” as the term is generally understood.

Annexation?

Regarding annexation, Levy writes, “Over a third (38 percent) of the Jewish public wants Israel to annex the territories with settlements on them, while 48 percent object.”

Actually the question said, “Would you or would you not want Israel to annex all the territories in which settlements are located?” to which 48 percent said that they “oppose annexation”, therefore suggesting support for a two-state outcome, which is consistent with other polls.

Blogger Avi Mayer, who first obtained and published the complete survey data, also notes that the term “territories in which settlements are located” is rather ambiguous. He writes:

“the pollsters clearly did not mean the entire West Bank (‘the territory of Judea and Samaria,’ as they refer to it in question 16). Did they mean the areas ‘controlled’ by the settlements (approximately 42.8% of the land, according to B’Tselem)? The areas likely to be annexed in the context of a peace accord (somewhere between 1% and 9%, depending which proposal is under discussion)? The settlements themselves (a mere 0.99%, per B’Tselem).”

The question was also ambiguous as to timing – annex them now, eventually, as part of a peace deal involving land swaps, or what?

Levy also highlighted that “a large majority of 69 percent objects to giving 2.5 million Palestinians the right to vote if Israel annexes the West Bank”.

Although, most Israeli Jews polled did not support annexation, perhaps largely because they do not want to face the dilemma of either granting Palestinians there citizenship, jeopardising Israel’s status as a Jewish homeland, or not doing so, thus severely compromising Israel’s democracy. However, the poll did not provide respondents with the option to answer, “I would be opposed to annexation.” Given this, it would be natural for many respondents to answer the question “no” as a way to express opposition to the general idea that Israel should annex the West Bank.

As Noam Shelef wrote in the Daily Beast:

“The poll actually shows that Israelis want to separate themselves from the West Bank, not even annexing the major settlement blocks. Only in a hypothetical situation-whereby their preference that Israel not annex the West Bank is ruled out by the pollster-do most Israeli Jews show a willingness to rule over non-voting Palestinians and thus tolerate apartheid. So claiming the poll demonstrates support for ‘apartheid’ is spin at its worst.”

Separate roads?

Levy writes, “A sweeping 74 percent majority is in favor of separate roads for Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank. A quarter – 24 percent – believe separate roads are ‘a good situation’ and 50 percent believe they are ‘a necessary situation.'”

However, it is not true that 74 percent “favour” separate roads. The question asked was “In the territories there are roads that only Israelis are allowed to drive on and others only for Palestinians. Which of the following opinions is closest to your opinion?” to which 24 percent responded “it’s a good situation” and 50 percent said “it’s not a good situation but there is nothing that be done”, meaning that its necessary on security grounds and 17 percent said ‘it’s a bad situation and should be stopped.’

Therefore, in fact, 67 percent of Israelis Jews polled said that the existence of separate roads in the West Bank is “not good” with a majority prepared to tolerate this situation only as a temporary security necessity.

Discrimination?

Levy uses the poll and his analysis to promote a belief in widespread discrimination – and indeed some of the attitudes express in the poll were concerning. He writes:

“A third of the Jewish public wants a law barring Israeli Arabs from voting for the Knesset…” and notes that the “majority of the Jewish public, 59 percent, wants preference for Jews over Arabs in admission to jobs in government ministries. Almost half the Jews, 49 percent, want the state to treat Jewish citizens better than Arab ones; 42 percent don’t want to live in the same building with Arabs and 42 percent don’t want their children in the same class with Arab children.”

However, he could have equally have highlighted that nearly two-thirds of Israeli Jews polled are opposed to denying Israeli Arabs voting rights.

As Avi Mayer writes regarding denying Israel-Arab voting rights:

“a large majority of 59% — including 77% of secular Israelis, 51% of traditional Israelis, and 44% of religious Israelis — oppose such a measure. This figure did not appear in either Haaretz piece. (Interestingly, there is more support among Jewish Israelis for preventing new immigrants from voting in the Knesset elections during their first year in the country — 41%, with a majority of 53% opposed. This is addressed in question number 5.)

Yes, 42% of Jewish Israelis say it would “bother them” if an Arab family lived in their building. But a majority of 53% — including 68% of secular Israelis and 47% of traditional Israelis — say it would not bother them. This figure did not appear in either Haaretz piece.

So when Levy writes that ‘the majority doesn’t want Arabs to vote for the Knesset, Arab neighbors at home or Arab students at school,’ he is not only producing false information and contradicting himself — he is actually presenting claims that are diametrically opposed to the reality presented in the survey. In fact, a large majority of Jewish Israelis do want Arab citizens to be able to participate in the democratic process, a majority would be perfectly comfortable living with Arab families in the same building, and a plurality would be fine with their children going to school with Arab peers. These findings represent a clear rejection of the hypothetical expressions of racism presented in the questions.”

Of course, to the extent that the poll is credible, it does have some disturbing results on Arab discrimination, and racist attitudes. However, there are some additional likely reasons that the numbers are so high in an Israeli context. One is that there is a situation of recent armed conflict between Israelis and Palestinian within Israel, with Israeli Arabs having occasionally helped carry out terror attacks during the 2000-2005 second Intifada. Fears of Arab support for violence against Jews – in schools and or in your home – are not completely irrational.

In addition, the Israeli version of multiculturalism does see more separation between communities than Australians would be used to. Israel has several separate public school systems designed to meet the needs of different groups, including a school system in Arabic for Israeli-Arabs, as well as different school systems for the Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox. Similarly, communities often live separately – though this is increasingly changing – with predominantly Arab, ultra-Orthodox, Orthodox and secular neighbourhoods and towns. Arabs sharing schools and apartments with Jews are a rarity in many parts of Israel.

Further, most of the opposition to Arabs at schools and in their apartments came from the ultra-Orthodox – who do not want even secular Jews to share their schools and apartments. They tend to view such outside influences as threatening to their insular religious lifestyle (they also reject television, for example.) This is not racism, but a different kind of insularity directed against all outsiders.

Discrimination exists in all countries, even in Australia, and the Israeli government, High Court and NGOs are making concerted policy efforts to address discrimination, for example 40 percent of the residents of Israeli national priority areas are Arab, while they are 20 percent of the Israeli population, and research suggest the situation has significantly improved (see previous blog post).

Even activists for Israeli-Arabs, Ron Gerlitz and Batya Kallus have recently conceded in +972 Magazine, while not perfect, that there has been significant improvement in addressing these issues:

“Nonetheless, anyone reading criticism directed toward the government’s policies regarding Arab citizens might think that all of the government activities and those of the government bureaucrats are aimed against Arab citizens, and that all of the efforts to advance equality policies have failed. This is not the case.

A combination of circumstances, among them the pressure brought by Arab society, advocacy by Arab civil society and shared society organizations, efforts by Hadash and the Arab political parties, as well as young people and others, have had an impact. Over the last ten years, the government has begun to initiate significant and innovative processes to close the gaps of inequality, advance economic development, and promote employment for the Arab population.

We are interested in giving some examples. Not because of our enthusiasm from the government’s activities, but rather because of our interest in strengthening these efforts. In 2003, the representation of Arabs in government service was 5 percent. Since then, there has been a steady increase, and by 2011 it had reached 7.8 percent (an increase of more than 50 percent). The number of Arabs employed in government civil service rose in the same time period from 2,800 workers in 2003 to 5,000 in 2011- an impressive increase of 78 percent, especially in comparison to a 12 percent increase in the number of Jewish workers during the same period. This represents a dramatic increase that is the result of focused policies to advance fair representation of Arabs in government service. (Contrary to the popular claim that the increase in Arab government employees is only the result of an increase in Druze employees.)

After years of neglect, The Ministry of Transportation initiated a process to introduce public buses to Arab communities and has succeeded so far, in Rahat, Kfar Kassem and other communities.

The Ministry of Welfare is systematically closing the gaps in the allocations of welfare budgets between Jewish and Arab communities, and is operating a variety of programs giving clear budgetary priority to funding of Arab municipalities.

The Ministry of Housing and Construction is successfully marketing the development of new housing on state-owned land in Arab communities in Nazareth, Umm Al Fahem as well as other communities.

In the field of employment, the government is running a number of programs to encourage Arab employment and has recently initiated an extensive and comprehensive process leading to the establishment of 22 employment guidance centers in Arab communities. Funds have been budgeted and implementation has begun…

In addition to the government, philanthropy- Israeli, international and especially the Jewish community in the United States are investing in improving the situation of Arab society. This is especially so in the areas of education and employment. We are talking about significant, long-term investment leading to impressive successes. For example: the expansion of high-tech in Nazareth in the last few years (there are more than 300 Arabs currently working in high tech in Nazareth as compared to 30 in 2008); and the success at the Technion which with the support of philanthropy has reduced the dropout rate of Arab students from 28 percent to 12 percent. The philanthropic sector is also active in supporting effective pressure on the government, and causing its agencies to expand its activities in the field of economic development…

Whatever the reasons and the factors for these changes are, the bottom line is that the government of Israel through its professional staff in government ministries is closing the gaps in many fields. Yet, there are many voices in Arab society who deny this trend, claiming that there is an overall decline in every field and that the advances are marginal at best.”

Sharyn Mittelman

Tags: Israel