FACT SHEETS

RESOURCES

Fact Sheet: Myths and Facts about the growth of Israel’s West Bank settlements

September 16, 2022 | AIJAC staff

A frequently repeated talking point on the Middle East is that Israeli building in settlements in the West Bank is supposedly taking up more and more land and making Palestinian statehood unviable. It is often also implied that the rate of expansion of settlements is rapidly increasing. A typical example summarising this “conventional wisdom” was the claim by former Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr in an interview on SkyNews in 2017:

This explosive expansion of settlements… are smothering the prospect of a Palestinian state and therefore a two-state solution. Settlements are gobbling up the land.”

These sorts of claims are based on a series of fundamental misunderstandings about the nature, scope and rate of Israeli building in West Bank settlements – largely spread via misleading statements made by pro-Palestinian groups and anti-settlement international and Israeli NGOs. This factsheet presents some basic evidence to allow the discussion of Israeli settlements to take place on a factual and informed basis.

Settlements take up less than 2% of West Bank land

The footprints of Israeli settlements take up under 2% of the land area of the West Bank, a fact agreed even by various sources generally critical of Israeli policies. For example:

- The BBC published a series of maps as part of a fact sheet called “Israelis and Palestinian in-depth”. Of the West Bank it says:

Since 1967, Israel has pursued a policy of building settlements on the West Bank. These cover about 2% of the area of the West Bank and are linked by Israeli-controlled roads…

- The BBC number is actually probably too high. This is clear from some work done by B’tselem, an Israeli NGO highly critical of Israel’s activities in the West Bank, including all construction in settlements. B’tselem commissioned a detailed survey of the West Bank to determine the degree of settlement control and published a highly critical report in 2010. Its survey showed that the “built-up area” of settlements constituted a mere 0.99% of West Bank land. As noted below, this percentage is very unlikely to have increased in any substantive way in the year’s since then.[*]

- In 2011, then-veteran Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat gave an interview with the Arabic radio station As-Shams about the 2008 negotiations with the Olmert Government, and stated that the settlements were approximately 1.1% of the West Bank, according to an aerial photograph provided by European sources (this was reported in the left-leaning Israeli daily Haaretz.)

The Israel Government has built exactly one new settlement over the last 20 years – and that was an unusual situation

Israel has authorised only one new West Bank settlement since 1999. In 2017, in the aftermath of negotiations between the Israeli government and settler groups following the evacuation of an unauthorised settlement outpost by court order, the Israeli government of the day approved the creation of a new West Bank settlement called Amichai, built on State land. It was, according to the New York Times, the first new settlement to be approved in decades. Before that, the last new West Bank settlement founded was Bruchin, established in 1999.

Settlement growth is generally not incorporating new land into settlements

Almost all new construction in settlements is taking place inside the boundaries of the settlements – in many cases not expanding the footprint of the settlement at all, in others expanding only within the settlement’s defined boundaries.

The fact is, since 2003, Israel has had in place policies that in almost all cases forbid the geographic expansion of existing settlements.

These are arrangements that the Israeli government negotiated with the Bush Administration in Washington that no new West Bank settlements can be built and existing settlements cannot expand territorially. Any construction in them is only in built-up areas. As then Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon said in a major policy speech in December 2003:

Israel will meet all its obligations with regard to construction in the settlements. There will be no construction beyond the existing construction line, no expropriation of land for construction, no special economic incentives and no construction of new settlements.

These arrangements remain Israeli government policy to this day, and remained the case even under the Trump Administration – without a doubt the US government with the least antipathy towards Israeli West Bank settlements.

At the same time, on at least three separate occasions – in 2000, 2001 and 2008, Israel has offered the Palestinians concessions for a final peace agreement that would have Israel evacuate dozens of isolated settlements and retain only the settlement blocs in exchange for mutually agreed land swaps with territory inside Israel. In every instance, the Palestinians broke off talks without providing a counteroffer.

But isn’t it true that Israeli settlement activity has been surging at a breakneck pace over recent years?

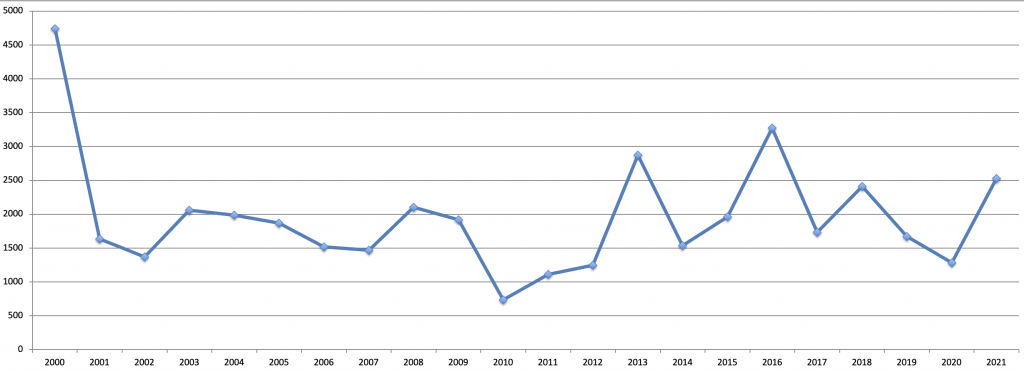

The statistical facts simply don’t support any such claim. A review of housing starts in Israeli settlements in the West Bank over the last two decades or so is remarkable for its lack of consistency. Some years saw housing starts slow or stop almost entirely, some years saw them accelerate. 2016 saw a peak in housing starts, but starts have been substantially lower every year since then, reaching an eight-year low in 2020.

HOUSING STARTS ANNUALLY SINCE 2000

Contrary to the narrative often seen in the media, these statistical indicators clearly don’t support the claim of an Israeli government settlement policy aimed at expanding Israeli control in the West Bank or preventing the creation of a Palestinian state.

Rather, if anything, these zig-zagging numbers seem to paint a perplexing and sometimes self-contradictory picture, on an institutional and national level, of a confused Israeli government policy that hasn’t decided what to do about the future of the West Bank in the absence of a peace agreement.

Settlement housing construction has not even been keeping up with “natural growth”

Overall, for more than a decade, Israeli settlements have been allowed to grow only at a very conservative pace that fails to even meet the demand for “natural growth”, via births, of the population living in the settlements. In statistical terms, while settlers comprise 3.91% of Israel’s population – and have on average more children than median Israeli families – over the past five years they have only been the beneficiaries of 3.35% of Israel’s new housing starts, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics. This means that the amount of building permits granted to the settlers isn’t even sufficient to provide the children of settlers a housing supply to be able to buy homes in the same settlement as their parents, let alone accommodate people interested in relocating to settlements from inside Israel proper.

By supporting limited settlement growth as a matter of maintaining the status quo, and allowing the existing settlements to expand housing modestly to accommodate some natural population growth, the Israeli government continues a policy of affirming the right, in principle, of the Jewish people to choose to make their home in the land where historically the Jews became a people – without prejudice to the possibility of the vast majority of the West Bank becoming part of a future Palestinian state following a peace agreement.

What about the illegal settlement outposts I keep hearing about? Aren’t they new settlements?

They aren’t the same thing, and in fact are very different. Settlement outposts, unlike authorised settlements, are not sanctioned by the Israeli government and are often targeted for removal by Israel’s government, courts and military.

Built not only outside of government permission but in defiance of it, there are 155 of them. Some of them have existed for many years, even decades, but almost all are very small. Situated in Area C, which under the Oslo Accords is territory under Israeli administrative and security control, most outposts are built on hilltops adjacent to existing settlements or as farms maintained by just a handful of settler activists.

The fates of many settlement outposts are often tied up in Israeli courts, in legal battles that drag on for years, which can and often do lead to the outpost’s evacuation. Moreover, when settler activists attempt to build new outposts, they are usually razed by the army, sometimes only to be rebuilt by activists in a game of cat and mouse. Occasionally, an outpost will obtain a favourable judicial ruling allowing it to remain. In February 2022, Israel’s outgoing Attorney-General Avichai Mandelblit ruled that a small Jewish rabbinical college, with living quarters, could remain indefinitely at Evyatar, the site of one of the newest outposts, erected by settlers after a deadly terror attack in 2021.

The existence of the outposts remains a thorn in the side of Israeli governments and does harm to Israel’s image. Yet they do not pose a significant obstacle to any future peace agreement since they are not supported by the Israeli government, are mostly inhabited by transients, lack permanent infrastructure and can be removed quickly by Israeli security forces – as many have been in the past, and continue to be at present.

Illegal building in the West Bank is not solely the provenance of Israeli settlers

In fact, while not widely reported, illegal Palestinian construction in Area C is far more prevalent than illegal Israeli settler outpost activity.

Therefore, the problem of unauthorised Israeli settlement outposts can’t be separated from the context of the larger territorial dispute between Israel and the Palestinian Authority over the rights to State lands located in Area C.

As noted above, under the Oslo Accords, Area C is to remain under Israeli security and administrative control pending a final status agreement that the Palestinian Authority has thus far refused to negotiate. Until that time, by mutual signed agreement, only Israel has the authority to issue building permits for new construction, regardless of whether the beneficiaries are Israelis or Palestinians.

Yet according to the NGO Regavim, the Palestinians have built 5,097 unauthorised buildings in Area C from 2019-2021 alone, bringing the total of illegal Palestinian-built structures in Area C to 72,274. In addition, the Palestinian Authority has launched agricultural projects in an effort to claim ownership over state land – similar to Israeli settlement outpost farms in practice, except reportedly spearheaded by the Palestinian Authority government directly. Many of these projects, in blatant violation of the Oslo Accords, are funded by the European Union. Palestinians argue that they have to build illegally because Israel does not issue enough permits, but the scale and scope of the Palestinian building projects suggest a “strategic” policy to encourage Palestinians to move into Area C to create “facts on the ground,” according to Regavim. Far from a hidden agenda, this was the publicly-stated strategic goal of former Palestinian Authority Prime Minister Salaam Fayyad, in a policy that is known as the Fayyad Plan.

Isn’t settlement activity a violation of the 1993 Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestinians?

Not at all. Neither the Oslo Accords, nor any subsequent signed Israel-Palestinian agreement, put any restriction on settlement growth in Area C, the Israeli-controlled area of the West Bank.

Article 5, Section 3 of the Oslo Accords, which deals with what will be discussed during permanent status negotiations, makes it clear that the future of the settlements would be resolved only through direct negotiations between the two parties. No other article limits construction of or in settlements.

Moreover, this was confirmed in 1997 by then-US Secretary of State Madeline Albright, who told NBC that while she disagreed with an Israeli decision to build new dwellings in the West Bank settlement of Efrat, “it’s legal”. Asked by Reuters if Albright was changing US policy of ambiguity regarding the legal status of Israeli settlements, her spokesperson James Rubin clarified that “All she meant by that was that as a technical matter, Oslo does not prohibit the settlements” or “[the construction of additional] housing in [the West Bank settlement of] Efrat.”

Are settlements the key obstacle to peace, standing in the way of a peace agreement and a Palestinian state?

Israeli experts best-informed on the extent and geography of settlement growth – even when extremely critical of that growth – generally acknowledge that the claims that it has destroyed or is about to destroy the two-state solution are not correct.

Here are two examples:

- Col. (res.) Shaul Arieli is one of Israel’s leading experts on borders and the separation barrier. During his IDF career he has served as commander of the Northern Division in Gaza, deputy military secretary to the Minister of Defence and the Prime Minister, and head of the administration for negotiations with the Palestinians. He is also a peace activist, and one of the founders of the “Geneva Initiative”, which put forward a plan for a two-state peace agreed on by Israeli and Palestinian civil society groups. In 2013, he published a study of the settlements in which he concluded:

Regardless of where one stands on the wisdom or otherwise of past or future settlement construction in various parts of the West Bank, creating a border between Israel and the West Bank remains entirely possible…The picture outlined here of the demographic and settlement reality in the West Bank shows that the real difficulty in implementing the idea of partition is not physical but political.

- Similarly, Lior Amihai is head of Peace Now’s “Settlement Watch” project, which monitors construction in settlements in the West Bank and east Jerusalem and is highly critical of all such building. He is as knowledgeable as anyone about the extent of that construction, yet when he was asked in a 2014 interview whether he thinks “we’re still, in principle, in the area of an [Israeli-Palestinian two-state] agreement being possible with land swaps?” Amihai replied, that while he felt currently Israeli settlement policies were unhelpful:

My view is clear: if the parties were to reach an agreement today then the two-state solution is very possible… I’m certain that if there was a true desire to reach a solution, it would be possible. It could be done so the majority of settlers stay in their homes and would not need to be evacuated.

This has not changed over the past few years, as confirmed by noted expert David Makovsky of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. His study from earlier this year “Beyond the Blocs: Jewish Settlement East of Israel’s Security Barrier and How to Avert the Slide to a One-State Outcome” is a follow-up to his 2010 study, “Imagining the Border”, which looked at various possible models of how the borders of a two-state peace deal could be agreed.

Taking into account everything that has happened since that time, Makovsky says that Israel’s settlement activity over the past decade has not altered the balance in settlement growth or the prospects for a possible two-state peace.

He notes that the overwhelming majority of settlers live in settlement blocs near the 1967 armistice lines, as in the past, which can be retained by Israel relatively easily through “land swaps”. Makovsky does stress the need for Israel to continue to preserve a viable two-state option with the Palestinians even in the absence of a credible Palestinian peace partner in the foreseeable future, and urges the Israeli government to stand up to the extreme fringe of the settler movement that is constantly planning moves on the ground to make such a resolution harder to attain. Yet Makovsky also argues that such a threat to future peacemaking hasn’t materialised yet.

Originally published May 2015. Updated September 2022.

[*] B’tselem chooses to focus its publicity for the report in question on the fact that municipal and regional councils associated with the settlements had theoretical legal jurisdiction over 42% of the West Bank, but this figure is largely irrelevant. This is municipal jurisdiction – ie zoning, planning, responsibility for local road maintenance – over mostly empty land. This land can become part of a future Palestinian state essentially at the stroke of a pen.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians, settlements