IN THE MEDIA

Israeli democracy shows ‘true strength’ in troubled times

April 9, 2023 | Justin Amler

The Australian – 7 April 2023

Late last month Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu announced a pause on the judicial reform proposals that have spurred mass protests around the country over the last three months. He did so, he said, to allow for negotiations with all parties to attempt to reach a broad consensus.

This has been a difficult period for Israel, as hundreds of thousands of ordinary citizens stood up against what they regarded as an attack on their democracy, leading even to a general strike. There have been many inflammatory statements from all sides, accusing each other of stoking civil unrest or attempting to subvert democracy.

In many ways, it left the country wounded and divided.

Many enemies of the Jewish state were buoyed, insisting that recent events prove, just as they have always said, that Israel is an artificial “colonialist entity” alien to the region, destined to collapse. None of this is true.

If anything, we have seen not the weakening of Israeli democracy, but an exhibition of its true strength. Israeli democracy worked – ordinary citizens expressed their democratic right to voice their opinions on issues important to them – and did so passionately and almost wholly peacefully.

There were instances of intimidation and incitement, but nothing compared to what happens in other Western liberal democracies.

An example is the violent protests taking place right now in France, after President Emmanuel Macron used special powers to force through a rise in the pension age without parliamentary consent. That’s a little ironic considering Macron strongly criticised Israel’s judicial reforms in February, claiming they called into question Israel’s democratic credentials.

And the Israeli protests were nothing like the attack on the Capitol in Washington on January 6, 2021, by supporters of defeated US President Donald Trump.

Here are the important basics about the recent crisis. Israel’s Government was elected democratically and thus has a legitimate mandate to carry out judicial reforms. Moreover, there is fairly broad agreement in Israel that some systemisation and limitation of the powers of the extremely powerful Supreme Court is necessary.

Nevertheless, despite its mandate for judicial reform, the government handled the reforms extremely badly. After four years of political deadlock and five inconclusive elections since 2019, the narrow victory achieved by a coalition of right-wing and religious parties last November created a heady determination to rapidly push forward long-delayed policy goals.

The government rushed to implement its agenda in its purest and most extreme form, without bothering to even attempt consultation or consensus-building. But it soon learnt that in a liberal democracy, even a parliamentary majority does not give unlimited power.

By moving far too quickly and essentially combining almost all previously discussed reform proposals into one massive package, it allowed the antireform camp to convince much or even most of the public that the judicial reforms were an attack on democracy.

Because Israel lacks a written constitution or bill of rights, and has only a unicameral parliament, the courts, especially the Supreme Court, are widely considered a bastion for both protecting human rights, and providing the primary check on the power of the majority in the Knesset.

Opponents of the reforms were thus able to assemble the biggest protest movement in Israeli history, reaching a crescendo early this week when Netanyahu sacked his widely respected Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, after Gallant went public with warnings he had issued privately that the reforms were harming the readiness of the army. With 600,000 angry people in the streets, Netanyahu had little choice but to pause the reforms.

The antireform protesters succeeded in part because they focused on Israeli patriotism, ensuring the demonstrations were flooded with the blue and white national flag, while avoiding involving controversial issues likes LGBTQ rights or the Palestinians. This allowed almost all sectors of the Israeli public to join in, even if they disagreed on the other issues.

But probably the most effective tactic they found was also the softest spot in Israeli society – the IDF. No institution in Israel symbolises unity and respect more than the Israeli Defence Forces because, given Israel’s severe security challenges, without it, there is no Israel.

In recent weeks, reserve soldiers from all units, including the most elite, refused to report for reserve duty, in support of the protests, arguing the Government was jeopardising the democratic norms they were fighting for.

Defence Minister Yoav Gallant was reportedly shocked to learn that up to 30 per cent of reservists had failed to heed their call ups to serve.

The government was forced to learn that social cohesion is key to Israel’s security.

In coming weeks, a middle ground must be found to rebuild that social cohesion, including implementing necessary reforms, but only after building a broad national consensus.

But make no mistake, while Israeli democracy certainly experienced testing times over recent months, overall, it appears to be passing that test with remarkable resilience.

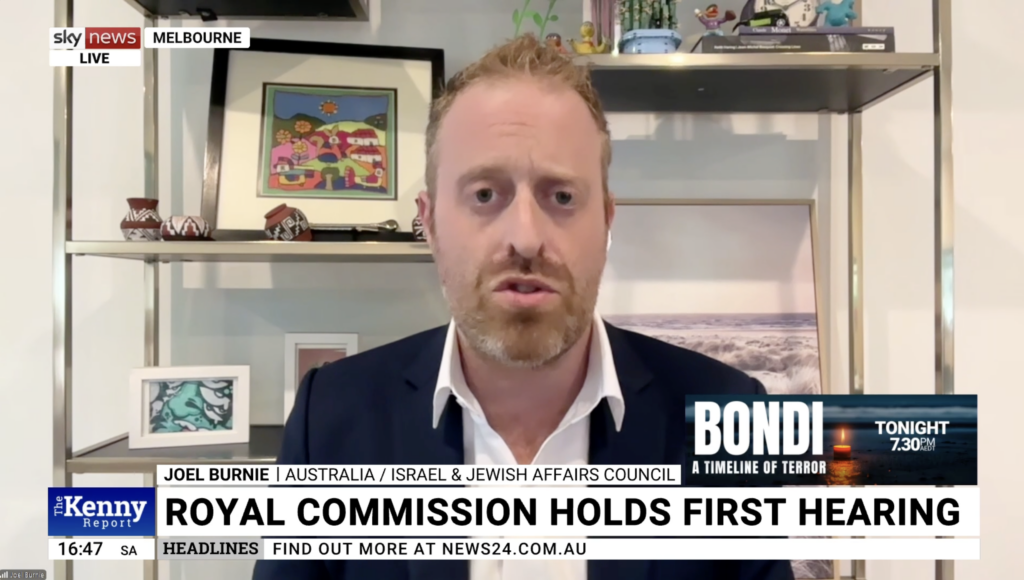

Justin Amler is a policy analyst at the Australia-Israel & Jewish Affairs Council

Tags: Israel, judicial reform