FRESH AIR

The Axis of Resistance is not dead yet

December 19, 2024 | Oved Lobel

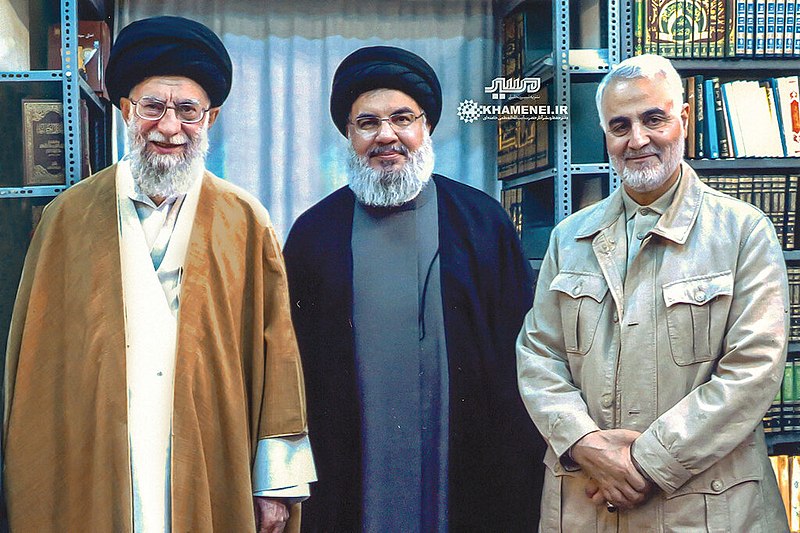

There is no doubt the “Axis of Resistance” has suffered severe setbacks in the past year. Hamas has been severely degraded as a military entity, with most of its leadership dead and prospects for full rearmament dim. Hezbollah’s leadership and command structure has been wiped out and its missile arsenal drastically reduced.

Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has lost multiple senior officials overseeing what was meant to be a multi-front war with Israel from Syria and Lebanon, including Brig. Gen. Mohammad Reza Zahedi; his deputy, Gen. Mohammad Hadi Haji Rahimi; and Brig. Gen. Abbas Nilforushan, the IRGC’s Deputy Commander for Operations. Iran itself has lost its air defence network and radar systems after two ineffective direct attacks on Israel, with its ability to produce ballistic missiles reportedly critically diminished following Israeli strikes.

Attacks from Yemen and Iraq against Israel employing hundreds of drones and missiles since 2023 have also been mostly ineffective, and the Houthi campaign to shut down international shipping via the Suez Canal and Red Sea, while generally effective at reducing and diverting shipping, has failed to translate into international pressure on Israel.

In the West Bank, where the IRGC has been smuggling in large amounts of weapons and explosives for several years to further stretch the IDF and reignite a third front alongside Lebanon and Gaza, Israel has managed to contain the violence with sweeping counterterrorism operations, and the Palestinian Authority itself has now begun attacking operatives of Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad and other groups in Jenin.

At the end of November, the rebel groups in Syria delivered what seemed to be the coup de grâce, launching a stunning 11-day offensive that rapidly brought down the regime of Bashar al-Assad, upon whom the entire concept of the Axis of Resistance has always hinged in terms of armament, training and strategic depth.

In addition, Russia has long been conjoined with the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and if the former is forced out of Syria, this could have serious consequences for resupplying Hezbollah or helping the Houthis target international shipping and potentially supplying them with more advanced anti-ship missiles.

Amidst these body blows, the reimposition of crushing “Maximum Pressure” sanctions by the incoming Trump Administration in the US is almost a certainty, further exacerbating the fragile position of the Iranian regime, notwithstanding the various methods Iran has devised to avoid sanctions, including trading with and through Malaysia, Turkey, the UAE and China.

However, it’s too early to declare the death of the Resistance Axis just yet.

The fate of Russia’s bases in Syria is still unknown, but if they are allowed to remain, then the IRGC will likely continue to rely on Moscow to supply Hezbollah with anti-tank missiles and other advanced weapons, albeit directly rather than through the previously more deniable channel of the Syrian army.

With the situation in Syria still so uncertain, and with the US likely to withdraw the small force there trying to keep the forces belonging to Islamic State contained next year, the IRGC has multiple avenues through which to smuggle weapons and maintain some influence, including its long-standing relationship with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) that currently still controls large swathes of northern and eastern Syria. There are still many routes open for weapons smuggling to Lebanon aside from this.

Turkey, too, has both competed and cooperated with the Axis of Resistance, including reportedly facilitating or at least turning a blind eye to IRGC arms shipments to Hezbollah during the 2000s.

There is also no guarantee that the Iranian regime will not develop friendly relations with the new Syrian Government, despite the former’s vital role in keeping Assad in power. This may seem outlandish, but even a cursory analysis of most regional wars in the last several decades would demonstrate how fluid alliances can be and how rapidly they can shift. Even if it does not come to an arrangement with the new Government, the IRGC thrives on instability and state weakness, and Syria is, at least for now, in flux.

The Houthis, meanwhile, are still fully intact and in control of most of Yemen’s population, and the IRGC still essentially controls Iraq. Hamas, while seriously degraded, is far from destroyed, and ruthlessly maintains overall control of municipal functions and aid distribution in Gaza. Hezbollah, too, can be rebuilt. Iran’s nuclear program, meanwhile, is too advanced to be halted barring extensive airstrikes by the US, and even that would not guarantee the end of it. Its ballistic missile production capacity will eventually recover.

This regime has shown itself to be remarkably durable and innovative when it comes to exporting the Islamic Revolution and attacking Israel, even under arguably worse domestic, regional and international circumstances than these. Barring a collapse of the regime or a coherent containment policy by the US and its allies – and despite whatever pragmatic and temporary retrenchment and policy adjustments may be necessary in the short term – it will attempt to regenerate the axis, and likely succeed.