UPDATES

Confronting terrorism after the Afghanistan withdrawal

September 4, 2021 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

09/21 #01

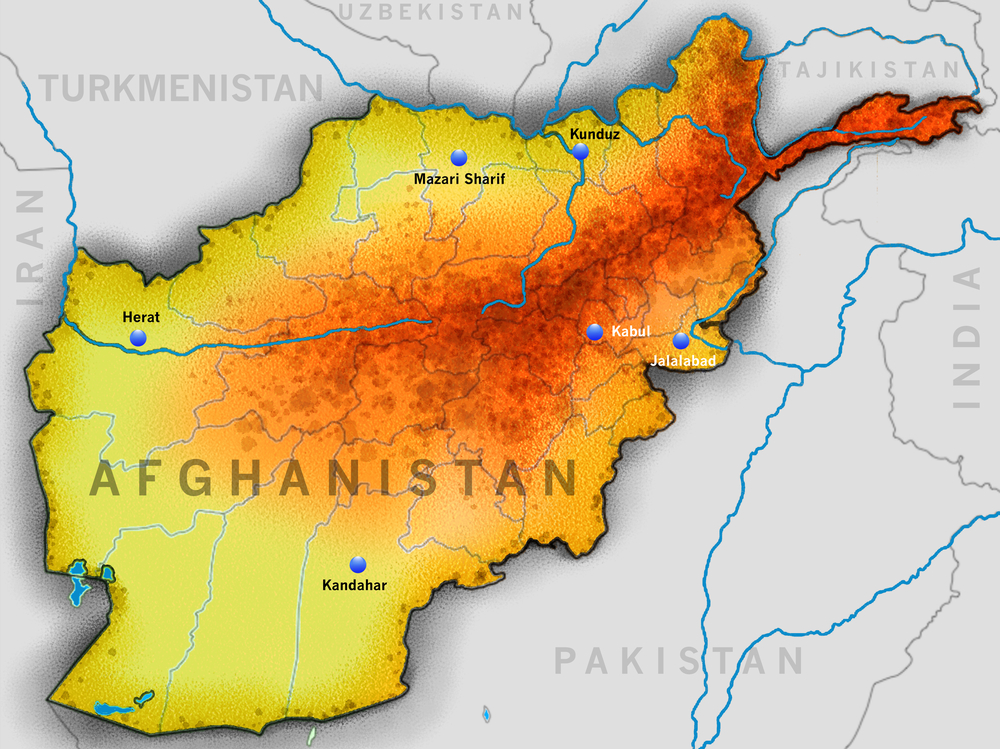

This Update collects some policy recommendations to deal with the likelihood of a surge of Islamist terrorism coming out of Afghanistan, in the wake of the country’s reconquest by the Taliban following the US withdrawal.

We lead with a Time magazine piece citing several top counter-terrorism experts laying out the likelihood of such a surge in terrorism. Experts like Washington Institute for Near East Policy scholar Matt Levitt warn that it is unlikely that the Taliban will be able to rein in groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS-Khorasan filling the vacuum in Afghanistan, even if they wanted to. The experts also warn that US plans to confront this problem with “over the horizon” capabilities look extremely difficult given the huge loss of intelligence assets in the country in the wake of the withdrawal. For more insights from Levitt and other counter-terrorism specialists, CLICK HERE.

Next up, two former senior US officials, Matthew Zwieg and Richard Goldberg, suggest some sanctions that could be swiftly implemented to deprive the Taliban and their al-Qaeda allies of the resources to carry out attacks abroad. They note that the Taliban has relied financially on illicit mining and narcotics production and trafficking for much of their revenue and sophisticated financial sanctions have been developed in recent years to deal with such illicit activities. They also urge that Afghanistan be declared a state sponsor of terror, along with a range of other measures that can be implemented quickly, hopefully to contain any major terrorist planning at an early stage. For their ideas in more detail, CLICK HERE.

Finally, we bring you some insights for dealing with Taliban-ruled Afghanistan from David Pollack, who, as a US government official in May 2001, wrote a memo warning that Taliban support for terrorism was an intolerable threat. Based on his long experience with Afghanistan since then, he offers several lessons for policymakers today. These include: do not look for “moderate” Taliban, which do not exist; make deals only if you can strictly enforce them; use money as leverage – but only incrementally and enforceably; and above all, provide allies with assurances there will be no more Afghanistans. For Pollack’s full argument, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- Former Israeli diplomat and academic Dr. Dore Gold explains why hopes that the Afghanistan withdrawal will not empower al-Qaeda look very doubtful.

- Veteran US reporter turned thinktank head Cliff May takes on the Biden Administration’s deferential attitude toward the Taliban.

- A good fact check on how much US military equipment the Taliban has reportedly captured – with some of this reportedly ending up in Iran.

- A letter from former Israeli General Ephraim Sneh to a counterpart in the Persian Gulf about what Israel and Arab states can now do in the wake of the US withdrawal.

- James Lindsay, a former lawyer at the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestinian refugees, writes about a missed opportunity to push through some reforms in that problematic organisation.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Colin Rubenstein’s op-ed in the West Australian, suggesting the US can help reverse its current image of defeat through a tougher stance on Iran.

- Judy Maynard on the links between the Al Jazeera network and the pro-Taliban policies of the Qatari government,

- Jeremy Jones on Israel-US relations in the wake of the Afghanistan withdrawal on SBS radio.

- AIJAC’s media release welcoming the Victorian Government’s announcement of reforms to strengthen anti-racism laws.

- Video of AIJAC’s webinar with former Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer, discussing “Australia’s Performance in a Challenging and Changing World.”

- A short video excerpt from Downer’s remarks in which he explains why he believes the Iranian regime cannot be trusted in its negotiations with the Biden Administration.

After a Rushed Exit, the U.S. Vows to Fight Terrorist Threats in Afghanistan from Afar

BY VERA BERGENGRUEN

Time, August 31, 2021

In defending his Afghanistan withdrawal, US President Joe Biden says that the US can address terror threats from “over the horizon”. Is he right? (Photo: archna nautiyal / Shutterstock.com).

Soon after the last U.S. plane departed Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport in the pre-dawn hours of Aug. 31, marking the end of America’s longest war, a Taliban spokesman posted a video message hailing “the result of 20 years of our historic sacrifices.”

“We left a historic chapter behind,” said Mohammed Naeem, according to a translation by CBS News. “The coming chapter is important.”

While U.S. officials broadcast the immediate security threats to efforts to evacuate Americans and Afghan allies in the chaotic final days of the war, they have been tight-lipped about what dangers may lie ahead. President Joe Biden defended his decision to pull U.S. troops from the conflict in a defiant address to the nation on Tuesday, noting that the terrorist threat to the U.S. has “metastasized across the world well beyond Afghanistan.” But the violent and harrowing withdrawal was a gift to terrorist groups looking to regroup there, experts say.

The U.S. has left Afghanistan in the hands of the same Taliban militants it overthrew two decades ago, after the group provided safe haven to the al-Qaeda operatives who plotted the 9/11 attacks. Its leaders still maintain close ties to al-Qaeda, and the nascent government being patched together in Kabul is unlikely to be able to contain the resurgence of competing terrorist groups in the region, including Islamic State in Khorasan Province. The group, known as ISKP or ISIS-K, has claimed responsibility for the Aug. 26 airport bombing that killed 13 U.S. service members and an estimated 170 Afghans.

“The vacuum created by the sudden end of the U.S.-led coalition in Afghanistan is going to be far larger than the Taliban can fill,” says Matthew Levitt, director of counterterrorism and intelligence at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. While there won’t be many American or foreign targets left in the country, for terrorist groups and foreign fighters “it will be an attractive place to flock to as a safe haven, a place to regroup, a place to plot, a place where they can comfortably exist and make plans for the future.”

The Biden Administration has vowed to keep such threats at bay from “over the horizon,” by monitoring the situation and deploying drones out of U.S. bases in Qatar and other Gulf countries. “We will maintain the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan and other countries,” Biden said on Tuesday. “We just don’t need to fight a ground war to do it. To ISIS-K, we aren’t done with you yet.”

But the dismantling of military infrastructure and withdrawal of all U.S. personnel from the country will make that task more difficult, experts and intelligence officials say, with the U.S. military now largely cut off from the human sources on the ground that it has relied on for twenty years. “We’ve had really good eyes and ears on the ground in Afghanistan,” says Colin Clarke, a counterterrorism analyst with security consulting firm Soufan Group. “And we’re still going to have ears…we’re still going to have [signals intelligence] capabilities, but we won’t have eyes.”

But U.S. defense and intelligence officials warn that won’t be enough to stop Afghanistan from once again becoming a hub for emboldened, more technologically savvy terrorist groups seeking to recruit, train, and plot attacks at home and abroad. “The Administration is right that our capabilities are far superior to what they were 20 years ago,” Clarke says. “But technology has been a force multiplier for jihadi groups too. It’s not like it’s the U.S. in 2021 versus al-Qaeda in 2001.”

The members of al-Qaeda left in Afghanistan, who could number up to 600, according to U.N. Security Council estimates, are now likely to have an opportunity to regroup and recruit, capitalizing on the perceived victory of jihad against the most powerful military in the world, analysts say. There have already been recent signs that the organization is ramping up its foreign propaganda operations: in June, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula recently released its first English-language copy of its “Inspire” magazine in over four years. “Foreign terrorist organizations continue efforts to inspire U.S.-based individuals susceptible to violent extremist influences,” Department of Homeland Security officials said in a bulletin released earlier this month.

“It’s a ‘rising tide lifts all boats’ situation,” says Clarke. “There’s going to be an influx of jihadi, some are going to go to [Al-Qaeda], and some are going to go to ISIS-K.”

This has been further complicated by the Taliban’s release of thousands of prisoners that had been in Afghan government custody, including many senior al-Qaeda operatives and members of ISIS-K, an offshoot of the original Islamic State group in Iraq and Syria. The group, whose leaders were targeted by the U.S.-led coalition in the final years of the war, has re-emerged and is already using the Aug. 26 airport attack in their propaganda material to raise its profile and boost recruitment, intelligence analysts say. ISIS-K has denounced the takeover of the country by the Taliban, which does not conform with its more hard-line version of Islamic rule.

But defense officials and experts say it’s unlikely the Taliban, distracted by the task of governing an impoverished country of 38 million people, will be able to rein them in. ISIS-K carried out 77 attacks in Afghanistan during the first four months of this year, according to U.N. counterterrorism officials, a significant increase from 21 in the same period in 2020. The U.N. security council warned in June of the “alarming expansion” of the group in the region and beyond, especially Africa.

Counter-terrorism expert Matthew Levitt: Terrorist groups will find Afghanistan “an attractive place to flock to as a safe haven, a place to regroup, a place to plot, a place where they can comfortably exist and make plans for the future.“ (Photo: Youtube).

A precipitous withdrawal could lead to a reconstitution of the terrorist threat to the U.S. homeland within eighteen months to three years,” a group of experts on Afghanistan, including retired Gen. Joseph Dunford, who served as the top commander in Afghanistan before he became the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 2015, warned in a report in February.

Biden and his top national security advisers have insisted that the U.S. will conduct effective counter-terrorism measures against these groups the same way they do in other countries where the U.S. does not have a permanent military presence. But former defense officials and experts warn that the sprawling post-9/11 U.S. security apparatus, built to rely on the collection of intelligence in Afghanistan, will become significantly less effective without reliable human intelligence on the ground, proximity or even an embassy, which for now will be operating out of Doha, Qatar.

“There is an expiration date to many of the collection platforms that we’ve been relying on over the past 20 years,” says Levitt of the Washington Institute, referring to Afghan sources and operatives the U.S. has used. “The likelihood that many of those will be disappeared over the coming weeks and months is unfortunately a very real threat.”

Beefed-Up Sanctions Could Limit the Damage in Afghanistan

The Taliban’s control of the government will significantly increase their wealth and influence.

By Matthew Zweig and Richard Goldberg

Wall Street Journal, Aug. 29, 2021

‘Our only vital national interest in Afghanistan,” President Biden said two weeks ago, “remains today what it has always been: preventing a terrorist attack on American homeland.” To prevent such an attack, Mr. Biden and Congress should swiftly work to deprive the Taliban and their al Qaeda allies of the resources required for attacks on the U.S. homeland.

While the Taliban have been subject to American terrorism sanctions for years, the group’s newfound control of Afghanistan’s government institutions and domestic resources will significantly increase its wealth and influence. If the new Taliban government’s central bank, ministries and agencies are not explicitly subjected to U.S. sanctions, the Taliban will be better able to use that money as it wishes. According to a 2020 United Nations Security Council report, before their takeover of Afghanistan, the Taliban operated a sophisticated financial network that generated between $300 million and $1.5 billion a year, primarily from illicit mining, narcotics production and trafficking, and taxation in areas they controlled. All these sources of income are likely to grow enormously as the Taliban consolidate control of nearly the entire country.

Al Qaeda remains intricately tied to the Taliban, so the new regime’s resources will be available to committed international terrorists. The U.S. military is now warning that al Qaeda’s operational capabilities are rapidly increasing. This should come as no surprise given that one of the Taliban’s deputy emirs, Sirajuddin Haqqani, is a longstanding al Qaeda ally and the head of the Haqqani network, an American-designated terrorist organization.

U.S. laws and regulations governing money laundering and illicit finance have come a long way since 9/11. Congress and successive administrations have developed sophisticated financial sanctions targeting terror-sponsoring regimes like Iran, Syria and North Korea. Washington should apply what it has learned to isolate the Taliban government and its terrorist allies.

Declaring the new Afghan government a state sponsor of terrorism would impose restrictive measures on trade and allow Americans harmed by Taliban-aided terrorists to pursue legal action against the regime. The State Department should also designate the Taliban a Foreign Terrorist Organization. While the Taliban is currently subject to financial sanctions under Treasury Department counterterrorism authorities, an FTO designation would further chill any interaction with Taliban-affiliated entities and expose anyone providing them support to extraterritorial criminal prosecution and civil liability.

President Biden should impose sanctions on Taliban officials, narcotics traffickers and mining operations—particularly rare earth metals. The Treasury Department should work to expand the guidelines and recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force—the international standard-setter for anti-money-laundering measures—to warn the global banking community further about the risks of terror and drug finance in a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan. And the State Department should assure Congress it can prevent the Taliban from diverting U.S. taxpayer-funded humanitarian aid before such assistance continues.

The Biden administration should also not back down on the important steps it has already taken to cut off Taliban financing. It should continue its freeze on Afghan Central Bank assets in the U.S.—more than $7 billion including $1.2 billion in gold reserves—and rebuff any request to repatriate them to the Taliban.

The administration should also continue to object to the disbursement of multilateral funds to Afghanistan, including through the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. As part of the IMF response to the Covid-19-induced economic crisis, Afghanistan was supposed to receive hundreds of millions of dollars this month—a transfer now on hold, presumably based on objections from Washington or European member governments. The IMF should never allow the Taliban to access any funds or financing. Nor should the World Bank, which last week suspended more than $2 billion in Afghanistan project funding.

The US Government needs to sanction those involved in opium production for the Taliban, and use the global financial system to cut off the financial benefits they get from such trafficking (Photo Credit: UN Photo/UNODC/Zalma).

These are all steps Mr. Biden and his administration have the power to execute quickly. If they demur, Congress can force them to act by legislation.

Twenty years after 9/11, the Taliban and their al Qaeda allies have retaken control of most of Afghanistan, putting themselves in a position to launch another attack. Targeting the Taliban’s financial networks is a critical first step to preventing one.

Mr. Zweig is a senior fellow and Mr. Goldberg a senior adviser at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

How Not to Repeat My History with the Taliban

by David Pollock

Newslooks, Sep 2, 2021

To avoid the worst outcomes, Washington needs to assiduously enforce any deals with the new Afghan leadership, cooperate effectively with other world powers, and explain to a domestic audience how the withdrawal will facilitate a focus on different priorities.

Afghan women – it is painful to see past achievements for them go up in smoke (Photo: timsimages.uk / Shutterstock.com)

The Taliban reconquest of Kabul is a trauma for many Afghans—but, one must admit, a triumph for others. Each competing segment of that society is living through something quite like a repeat of history. From my personal perspective, though mercifully far from the scene, it means reliving a professional nightmare that began in early May of 2001.

At that moment, as the regional expert in the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff who had followed the Taliban ever since their first arrival in Kabul, I wrote a formal memorandum to the Secretary about them. Its opening line (later cited in unclassified form in my official performance evaluation) read simply as follows: “The United States can no longer live with Taliban support for terrorism.” The evaluation commended me for that “stunningly prescient” warning, along with my proposed emergency preemptive measures. But by then, of course, it was too late; 9/11 had already happened.

Afterward, I spent the next five years as Senior Advisor for the Broader Middle East in State’s Office of International Women’s Issues, helping to launch initiatives like the U.S.-Afghan Women’s Council, the Secretary’s International Women of Courage Award, and vocational mentorship programs for Afghan women and girls. All the while, I had to keep a wary eye on Taliban and other opposition to these social transformations. Truth be told, credible surveys showed that Western women’s ways are still widely considered offensive by many Afghans.

Still, such projects were reasonably effective, despite all the well-known waste, corruption, cultural misunderstandings, and growing unpopularity—at home and in Afghanistan—that dogged the overall American experience in that country. Whatever the weak strategic rationale for our withdrawal, it is painful to see so much of that progress literally go up in smoke right now. But again, it is too late to lament this fait accompli.

So, now that the Taliban are once again in power, will the worst such tragedies recur? We cannot know for sure, so we should not waste much time on futile prognostications. We do know, however, that this is not inevitable; once again, the outcomes depend at least partly on what we do next. In that spirit, I offer seven lessons learned from previous chapters, with due allowance for all the changes that have taken place until today.

1. Stop trying to find “moderate” Taliban. There aren’t any who matter, though there are some tactical differences among them. I participated in many internal debates about this in the decade after the Taliban took Kabul the first time, all of which only confirmed my grim conclusion. Today I see little evidence that this has changed for the better. The possible inclusion of non-Taliban figureheads in some new Afghan government—even former president Hamid Karzai or chairman Abdullah Abdullah—will almost certainly not fundamentally alter this fact. Still, the tactical differences offer a window for bargaining, leading to the next suggestion.

2. Make deals with the Taliban—but only if you are prepared to enforce them afterward. Their credibility in negotiations with the West is near zero, so long as they believe they can get away with murder. Regarding Taliban support or tolerance for cross-border terrorism, which they are currently at pains to disavow, it would make sense to send very explicit and specific private warnings to them about U.S. determination to forcibly preempt or (if that fails) punish any violations immediately. And it would be essential to act on those warnings as the need arises.

The two or three U.S. strikes against Islamic State–Khorasan (IS-K) terrorists since the horrific Kabul airport suicide bombings were a start. But this needs to be a sustained campaign, not just a few parting shots; it needs to avoid further civilian casualties, which is exceedingly difficult; and it needs to be targeted against Al-Qaidah as well, not just against the avowed IS-K rival of the Taliban. If that can be done in coordination with the Taliban, fine, so long as it is done on a “do not trust, and verify” basis.

A new statement by the senior Taliban spokesman in Doha, Zabihullah Mujahid, reiterating his denial of any “proof” linking Bin Laden with 9/11, is a bad omen in this regard. Nevertheless, in many other Muslim-majority states, both public opinion and government policies turned hard against some of the most extreme jihadi groups after mass-casualty terrorism in their own cities. Perhaps the Taliban will eventually follow suit.

3. Use money as leverage. President Biden has publicly hinted that Taliban access to frozen foreign exchange reserves or international aid might be dependent on how they treat their own citizens, including female ones. This is worth a try. One Taliban official has just declared that this time around, women and girls will be allowed to work and go to school—but separately from men and boys. Idealists may argue that the Taliban should be sanctioned, not bribed. But that has never worked with them before.

To be sure, the Taliban don’t care much about economic development, and they have other income from the drug trade and similar skullduggery. Yet they probably want more, and may be willing to bargain for it. The key is to strike hard, incremental bargains, rather than give away (or take away) the whole store at once. And if the Taliban do not fulfill their end of the bargain, then the bucks should stop there.

More hopeful days – former Taliban fighters turn in their weapons in 2012 (Department of Defense photograph by Lt. j. g. Joe Painter/RELEASED)

4. Work with others—both friends and adversaries—to contain the Taliban and their kin. We have common interests with Russia, China, and even Iran in countering potential terrorist threats from Afghanistan. We have periodically engaged with each of them on this, fairly successfully, in the past, without prejudice to other issues. We should therefore intensify the effort to regain this common ground, notwithstanding the public gloating in those countries about the American “failure” in Afghanistan.

5. At the same time, the U.S. should strive to reassure our allies and partners, throughout the Near East/South Asia and beyond, that we will continue to support joint efforts against terrorists and in favor of our friends. That means clarifying our intention to maintain the very modest but crucial military advisory presence we have in Iraq, Syria, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere in the region.

In other words, there should be no more Afghanistans on the horizon. Senior U.S. officials have already conveyed that message to the Iraqi government, and to the Syrian Democratic Forces. But messages alone will no longer suffice; a demonstrated, continuing commitment on the ground will be required.

6. Explain how the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan will help us focus on bigger issues, like “great power competition” with China or Russia. We have heard plenty of vague talk about this, but specifics are sorely lacking. They need to be provided, and then proved in practice. If not, then this line of argument is not a real rationale but merely a rationalization for the U.S. withdrawal, feeding domestic political doubts. That leads to the final recommendation:

7. Work with others to restore some common ground at home. This may be the hardest task of all, but it is vital. To the maximum extent possible, the partisan or bureaucratic blame game about Afghanistan should be relegated to the sidelines for a while—as was the case with my own Taliban story. Only in that way will the upcoming twentieth anniversary of 9/11 become an occasion for renewed American resolve, rather than endless—and pointless—recrimination.

David Pollock is the Bernstein Fellow at The Washington Institute, focusing on regional political dynamics and related issues.