Article 2

Beloved – At Long Last

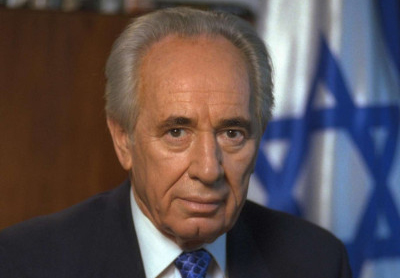

Shimon Peres’s lifelong quest for popularity encapsulated the frequently tragic voyage from Exile to Zion

Amotz Asa-El

Jerusalem Post, 30 September

“A car for every worker,” promised Shimon Peres in 1965 in one of the most original, tight, and catchy election slogans ever coined here.

Yet the setting in which it emerged would later loom as the dividing line between Peres’s years 18 as a prodigious technocrat and his 42 years as a controversial and often reviled politician whose rocky journey to public affinity is an emblem of the Zionist journey from despair to hope.

Shimon Peres died universally beloved, but he spent a political eon as the punching bag of political rivals, ideological enemies, and social discontents.

During 66 consecutive years in public office Peres proceeded from civil servant through politician to statesman, and at the same time also from brilliance through tragedy to improbable consolation.

The brilliance showed during his years as a technocrat, which began in 1947, when at age 24 David Ben-Gurion brought him into the circle with which he was creating the IDF.

Following assignments as purchaser of the IDF’s first battleships and fighter planes, Peres became director-general of the Defense Ministry in 1953, at age 30. It was the ultimate technocratic power job, an unelected position which placed Peres in charge of vast budgets and thousands of people while answering directly to an omnipotent prime minister who trusted him blindly.

This unique location in the public fray did not change even after Peres’s entry into the Knesset in 1959, because Ben-Gurion immediately appointed him deputy defense minister, a position in which the rooky lawmaker Peres effectively continued doing what he did until then – run the military-industrial complex.

It was in those technocratic years that Peres first displayed the combination of vision and provocation that would both dominate and haunt his career.

On the one hand, he built from scratch Israel’s military and aerospace industries that later made missiles, tanks, aircraft, satellites, an jets, but back then had yet to produce even their first Uzi. On the other hand, when he negotiated a groundbreaking arms deal with France he did it behind the Foreign Ministry’s back.

The result was a lifelong enmity with then-foreign minister Golda Meir, who would later sideline Peres as a minister in her cabinet.

The same pattern repeated itself with Israel’s nuclear program, a top-secret operation which Peres largely conceived and led, and of which hardly anyone knew until Ben-Gurion dramatically announced its completion. While privy to such secrets, Peres was sowing jealousy and making enemies, often passively, while enjoying Ben-Gurion’s personal protection.

It was against that background that Peres entered parliament in 1959 without working his way up from local politics and without ever being a backbencher. The price of this shortcut would prove hefty.

THE HARDSHIPS of real political life first hit Peres in 1965, when he coined that election slogan.

Ben-Gurion had split from Labor and launched a competitor, Rafi, which fielded some of the most promising young Israelis, like Moshe Dayan, Teddy Kollek, Chaim Herzog, and Yitzhak Navon, while claiming to represent Israel’s youth, courage and ingenuity. As Rafi’s secretary-general, Peres was now a party chief. That, not the transition to lawmaker, was his political baptism by fire.

It was a grand failure. Despite that sharp election slogan, Rafi won a mere 10 Knesset seats and ended up languishing in the opposition. When it joined the coalition two years later, in the wake of the approaching Six Days War, it was as Labor’s stepsister. Peres would only return to executive office in 1969, as a junior minister in Golda Meir’s cabinet in the years leading to the Yom Kippur War.

That war would transform Peres’s career, as it finally brought down Labor’s older generation and ultimately landed him in the defense minister’s seat, where he was tasked with rebuilding the bruised IDF – a challenge he stormed with relish and success.

However, while making the most of his technocratic experience, Peres-the-politician now found himself at loggerheads with Yitzhak Rabin. It was a rivalry that exposed Peres-the-technocrat’s other political weakness – his position as an immigrant bureaucrat among battle-scarred sabras.

Peres as Defence Minister greets commandos following the 1976 Entebbe raid – but despite his huge role in building the Israeli security forces, could not compete politically with war hero Yitzhak Rabin

Rabin, a warrior of few words and broken sentences, loathed the worldly bookworm with whom he was now compelled to share a political bed.

Having arrived here from prewar Poland at age 12, Peres’s efforts to emphasize his teenage years as a Galilean farmer in Kibbutz Alumot were no public match for Rabin’s record as the military commander who at 26 broke open the road to Jerusalem, and at 45 defeated three armies in six days.

Ironically, what Peres suffered as a perceived immigrant paled compared with what awaited him as a perceived veteran, in his troubled political career’s next phase, following Yitzhak Rabin’s resignation.

PERES REACHED Labor’s helm in 1977, just when it first lost power, and thus found himself in the thankless position of a declining elite’s defender, symbol, and lightning rod.

At a time when Menachem Begin endeared the second generation of the Middle Eastern immigrations, Peres became their antichrist, even though he had nothing to do with their perceived discrimination during the 1950s. Peres’s accomplishments as a technocrat were no match for the charismatic Begin’s effectiveness as an orator. In one particularly telling moment, the man who played such a central role in building Israel’s defenses had to be whisked away from an election rally in Beit Shemesh where hecklers pelted him with rotten tomatoes and eggs.

With Likud magnetizing anyone who felt marginalized by the veteran establishment – the Middle Eastern immigrations, the working class, the ultra-Orthodox, the modern Orthodox, and small-business owners – Peres did not manage to win an election even after Likud led to major economic crisis in 1984.

Absurdly, the immigrant who was kept at arms’ length by natives was now shunned by immigrants for whom he represented the native elite.

Even so, the electoral tie of 1984 made Peres prime minister, a position in which he momentarily became what had never really been: popular.

Challenged by 415-percent inflation, Peres imposed on the politicians, unions, and employers a harsh austerity plan that soon led the economy from near bankruptcy to stability, growth and wealth. Peres now loomed as a national savior.

Fueled by this backwind, the man who had built some of the West Bank’s first settlements now embarked on his next project: peace. It was a choice that would undo all the popularity he had worked so hard to win.

Peres’s original aim was to make peace not with Yasser Arafat but with King Hussein, and thus restore Jordan to the West Bank. As Yitzhak Shamir’s foreign minister, he struck a tentative deal with Hussein in London. However, Peres mishandled Shamir the way he mishandled Golda Meir in the 1950s, keeping him in the dark while hoping the prospect of peace would lead to Likud’s defeat.

It was the grand miscalculation of his entire career.

Hussein avoided public confirmation of the deal, Peres lost the election of 1988, and then also Labor’s leadership – to Yitzhak Rabin.

The subsequent Oslo Accords only intensified antagonism toward Peres as terror raged, before and after Rabin’s assassination. Peres won a Nobel Prize for peace, but he lost the 1996 election to Benjamin Netanyahu. Peres-the-statesman failed to deliver the goods that Peres-the-politician craved.

The road from there to his career’s most humiliating moment, the defeat by Moshe Katsav in the 2000 presidential election, was short.

Peres was now stung by a man who represented everything he was not: a lifelong politician who started off not as a builder of navies, air forces and nuclear reactors, but as a small-town mayor; a resident of not of posh north Tel Aviv, but of working-class Kiryat Malachi; an observant immigrant who, when Peres was in New York buying fighter planes, was a child en-route to Israel from Iran.

CHANGE CAME at 84, when Peres landed in the president’s seat after all.

Peres ended his career an almost universally beloved elder statesman – but in fact spent most of his public life struggling for recognition and acceptance

Enlisting all his wisdom and poise, Peres rehabilitated the office that had been bruised when Katsav was convicted of sex offenses. For seven years he spent his days greeting, visiting, and celebrating the simple people from whom he was distant in his years as a technocrat, and whom he failed to endear as a politician. Now they were his daily company, a company of which he seemed to never have enough.

For thousands, the journey from Exile to Zion resulted in tragedies of estrangement and exclusion. Peres embodied this syndrome, but unlike most of its victims, his tragedy now came undone.

Appeased, affable, and genuinely adored, the man who was once hated by thousands – became universally revered as the Zionist revolution’s Last Mohican, and Israeli society’s collective grandfather.

At long last, Peres embodied the consensus he had long defied, and also won what he had once belittled, later craved, and so seldom tasted: the people’s love.

BACK TO TOP |