UPDATES

The Killing of Baghdadi/ Lebanon in Chaos

November 1, 2019 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

11/19 #01

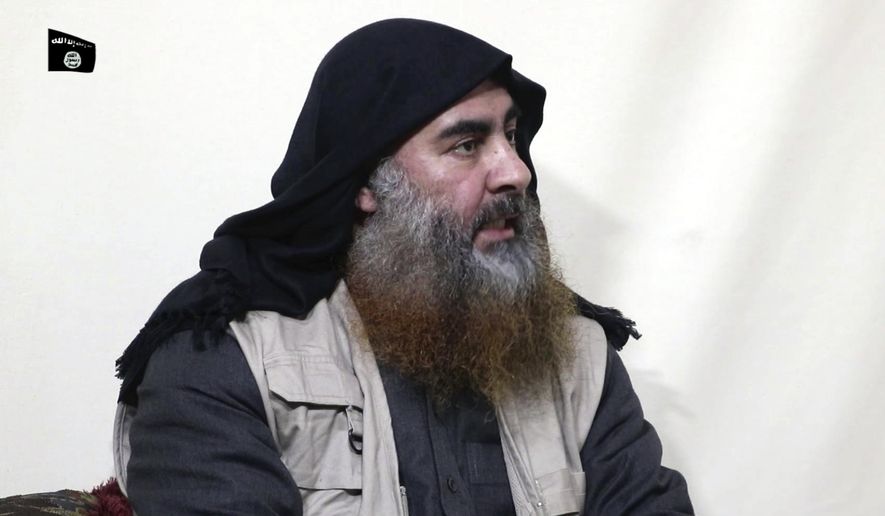

This Update deals with both the killing of Islamic State head Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi by US special forces last weekend and the ongoing mass demonstrations in Lebanon, which led to the resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri on Tuesday.

We lead with some analysis of the Baghdadi killing, from Cliff May of the Foundation for the Defence of Democracies. May argues that Baghdadi’s death is a battle won in the war on extremist Islamism, but that Islamist ideology will continue to march on without him and will still need to be vigorously fought. He notes that the ideology behind Baghdadi’s Islamic State is actually, at base, the same as that of the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Iranian regime and its allies, despite their apparent differences in terms of tactics and appearance, and urges that war-weariness must not be allowed to derail the battle against these destructive forces. For his full argument, CLICK HERE. More on what is known about the Baghdadi attack and its implications comes from Israeli counter-terrorism expert Ely Karmon.

Next up, Israeli Arab Affairs reporter Avi Issacharoff makes the case that the resignation of Hariri in Lebanon is actually a blow to Hezbollah, even though Hariri is ostensibly their opponent. Issacharoff says that Hezbollah was happy with the status quo in Lebanon, with Hariri as a tightly-constrained fig-leaf for Hezbollah domination, and recent events risk changes that Hezbollah cannot control. He also discusses the roots of the protests and Lebanon’s dim prospects for the future under the Hezbollah-dominated status quo. For all of his analysis, CLICK HERE.

Finally, Washington Institute for Near East Policy Lebanon expert Hanin Ghaddar looks at the wider regional implications of both the Lebanon unrest, and the similar protests in Iraq. She argues the events in both countries can be best understood as a reaction against Iranian domination which today is being exhibited even by Teheran’s traditional Shiite allies. She says Iran has been very adept at patiently extending hegemony over neighbouring countries – but the protests demonstrate that it lacks a socioeconomic vision to maintain its support once it has established that hegemony, as it has in Lebanon and Iraq. She has many more insightful things to say, and to read them all, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- More on Hezbollah and the Lebanon situation from American researcher Joe Macaron and Israeli strategic analyst Jacque Neriah. Plus, a report on the supply shortages in Lebanon as the crisis there escalates.

- The International Atomic Energy Agency – which monitors Iran’s nuclear program as one of its key tasks – has a new head, Argentinian diplomat Rafael Mariano Grossi. Analysing his election and the challenges he will face are Simon Henderson and Elana DeLozier of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

- Noted Israeli analyst and AIJAC guest Ehud Yaari is quoted by Greg Sheridan to explain the current Middle East situation in the wake of US President Trump’s Syrian retreat.

- Isi Leiber excoriates a World Jewish Congress award to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, arguing she is not worthy of it.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Naomi Levin discusses Canberra’s continued adherence to the JCPOA nuclear deal with Iran even as Iran openly breaches that deal, and the US continues to impose sanctions.

- Allon Lee explains the realities behind the Gaza situation in response to a poorly-informed promotion of a Palestinian film festival in the Hobart Mercury.

The Battle of Baghdadi

A victory, to be sure, but Islamism goes marching on

Clifford D. May

The Washington Times, October 29, 2019

The elimination of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a battle won. But it is not, by any stretch of the imagination, the end of the “endless war.” Islamism, in all its fury and diversity, goes marching on.

Five years ago, Mr. Baghdadi was proclaimed (by his followers) the caliph — successor to the Prophet Mohammed. Even Osama bin Laden was never so audacious.

The Islamic State in Iraq, a splinter from al Qaeda, had been organized in 2006. Eight years later it re-branded as the Islamic State — replacement for the Ottoman caliphate which collapsed less than a century ago, an historical blink of the eye.

At its zenith, the Islamic State occupied a territory the size of Great Britain, established “provinces” in a dozen other countries, ordered up terrorist attacks in Europe, and attracted volunteers from around the world.

Some young Muslim men came from impoverished lands where opportunities for meaningful employment and marriageable women were scarce. Others came from America and Europe, drawn to what they imagined would be an exciting lifestyle: wielding AK-47s, zipping around in the fighting vehicles known as “technicals,” slave-raiding, and occasionally slitting the throats of infidels and apostates.

Still others, men and women alike, regarded themselves as pious pioneers. They were eager to contribute to what they saw as the restoration of the power and glory that had been stolen from the global Islamic community by the forces of unbelief and their wayward Muslim allies.

The death of Mr. Baghdadi deals a devastating blow to the Islamic State. One obvious reason: His skills and stature will be difficult to replace. One not-so-obvious reason: In the theology to which Mr. Baghdadi subscribed, it is Allah who decides the outcome of battles and wars. That the caliph — not just a soldier seeking martyrdom — could be taken down by Delta Force operators and Army Rangers suggests to the faithful that his mission lacked divine endorsement.

Still, the Islamic State will attempt to reinvent itself. Military strategist David J. Kilcullen warned this week that it “may prove even harder to defeat in its next incarnation.”

It always surprises me how many government officials, academics and journalists, after all these years, remain confused about Islamists – who they are, what they believe, why they fight.

That was vividly illustrated by the headlines that appeared online Sunday morning over Jody Warwick’s otherwise informative Washington Post obituary of Mr. Baghdadi. The first read: “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Islamic State’s ‘terrorist-in-chief,’ dies at 48.”

Some Post editors apparently considered that insufficiently respectful of the deceased. The next version read: “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, austere religious scholar at helm of Islamic State, dies at 48.”

As “absurdly deferential as this headline is” noted M. Zuhdi Jasser, president of the American Islamic Forum for Democracy, “it confirms what Islamists – including those appearing in the pages of the Washington Post – strenuously deny: that Mr. Baghdadi was actually a respected ‘scholar’ of the global Islamist establishment.”

Post copy editors gave it another try: “Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, extremist leader of Islamic State, dies at 48.” That’s better, though a casual reader might assume he had slipped in the bathtub rather than been chased into a dead-end tunnel by American commandos.

Two questions strike me as worth further consideration. How odd it is to think of Mr. Baghdadi as “austere”? True, in his youth, he was offended “at the sight of men and women dancing in the same room,” as Mr. Warwick duly reports. But when he assumed the mantle of caliph, he “kept a number of personal sex slaves” including Yazidi women, and Kayla Mueller, an American hostage who eventually died in captivity.

As for Mr. Baghdadi’s Islamic scholarship, he had degrees from the University of Baghdad and the Saddam University for Islamic Studies to prove it. How well do you think a non-Muslim arguing that “Islam is a religion of peace” would have fared in a debate against him?

That said, I disagree with those on the far right who argue – as Mr. Baghdadi would have – that less belligerent readings of Islam should be dismissed as inauthentic and even heretical.

Which brings me to a final point that goes against the conventional grain: The ideology which Mr. Baghdadi espoused and the goals for which he fought do not significantly differ from those of al Qaeda, the Islamic Republic of Iran, and the Muslim Brotherhood.

True, Muslim Brothers prefer a tie and jacket to a turban and dishdasha. True, too, Iranian followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini may be well-educated, cultured, fluent in the language of diplomacy, and comfortable in the company of (friendly and compliant) unbelievers. Also true: The strategies these factions employ are not identical.

However, all believe in the imperative of Islamic supremacy, envisioning a world ruled by and for Muslims, one in which infidels are at least relegated to an inferior status. All believe in “Death to America!” And all are prepared to wage an “endless war” if that’s what it takes to achieve their objectives.

In a media statement on Oct 27, US President Donald Trump announces the killing of Baghdadi by US special forces.

In a media statement on Oct 27, US President Donald Trump announces the killing of Baghdadi by US special forces.

As Mr. Baghdadi’s followers mourn, what may give them hope is the war-weariness and isolationism rising on both the right and left in America.

President Trump deserves credit for eliminating the leader of the Islamic State. But I hope he now realizes that had he withdrawn all American forces from Syria months ago, cutting off the American partnership with the Kurds — who supplied critical intelligence on Mr. Baghdadi’s whereabouts — this mission could not have been accomplished.

Awful as the prospect of endless.war may be, conceiving a worse alternative should not require much stretching of the imagination.

Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and a columnist for the Washington Times.

Hariri’s resignation and Lebanon’s raging protests are bad news for Hezbollah

Avi Issacharoff

Times of Israel, 30 October 2019

The demonstrations that toppled the PM now aim to overhaul the entire failed political system in Beirut — which the terror group has relied on to stay in control

Lebanese PM Saad Hariri, pictured in front of a picture of his assassinated father, gives an address to the nation in Beirut, Lebanon, October 29, 2019, announcing his resignation. (AP/Hassan Ammar)

Lebanese PM Saad Hariri, pictured in front of a picture of his assassinated father, gives an address to the nation in Beirut, Lebanon, October 29, 2019, announcing his resignation. (AP/Hassan Ammar)

The resignation announcement Tuesday by Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri could have been expected to please Hezbollah. After all, Hariri — the son of former prime minister Rafik Hariri, who was murdered by Hezbollah emissaries in 2005 — is a longtime foe of the terror group.

But in reality, the resignation — like the protests raging across the country, which prompted it — is causing Hezbollah’s top brass a serious headache.

It is no coincidence that in his latest speech, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah railed against the rallies and issued an implicit threat to mobilize his staff “to prevent a [leadership] vacuum.”

Hezbollah supporters, left, burn tents in the protest camp set up by anti-government protesters near the government palace, in Beirut, Lebanon, October 29, 2019 (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

Hezbollah supporters, left, burn tents in the protest camp set up by anti-government protesters near the government palace, in Beirut, Lebanon, October 29, 2019 (AP Photo/Hussein Malla)

It is also no coincidence that Hezbollah members were filmed Tuesday storming the protest tents in Beirut, destroying them and harming demonstrators. Similar violent clashes have broken out several times over the past week between Hezbollah supporters and the protesters, who are demanding the replacement not only of the government but also of the regime system and the current ethnic divide of power that is crippling the country.

Hezbollah is comfortable with the status quo and with the current failing system. It manages to rule the country even without its members serving as prime minister or president. It controls the Lebanese army even though the chief of staff is Christian, and it sets the country’s foreign and domestic policies, while leveraging the inter-religious divide to maintain its power.

Hezbollah’s negative response to the protests mainly stems from its fear that the unrest gripping Lebanon since October 17 will spiral still further out of control. Criticism of Hariri is one thing, and is welcome as far as the terror group is concerned. But changing the regime system is another thing entirely, and could cause severe tension between the different ethnic and religious groups and potentially even far more violent confrontations.

A true revolution in the Lebanese political system would plunge the Shiite organization into an unknown future, which could turn out to be to its benefit — but the risk is too high at the moment.It does as it pleases throughout the country, including developing one of the biggest arsenals of rockets in the world and taking steps to turn them into much more dangerous precision missiles.

The fact that hundreds of thousands of Lebanese citizens — of all ethnicities and religions, including Shiites — have taken to the streets, is a direct result of the problematic political and economic situation in the country. Preserving the status quo is hurtling Lebanon toward bankruptcy.

With a huge number of Syrian refugees, with mounting unemployment reminiscent of places such as the Gaza Strip, with a swelling national debt, and above all with a paralyzed, rotten and corrupt political system, Lebanon’s future looks dim. Yet Hezbollah considers itself better off ruling such a country than betting on a normal, functioning Lebanon, with leaders seeking the benefit of the entire country rather than a specific sect or group.

Hariri’s announcement Tuesday that he is resigning is not particularly big news. He has resigned in the past and every such move was welcomed by Hezbollah. Over the years he has returned to the role and then again stepped down.

However, this time around, in light of the social, political and economic crisis, the resignation looks like it could eventually lead to all-out chaos, and even Hezbollah cannot predict how that will end.

Iran Is Losing the Middle East, Protests in Lebanon and Iraq Show

Tehran may be good at winning influence, but it is bad at ruling after that.

Hanin Ghaddar

Foreign Policy, October 22, 2019

Lebanese women take part in a demonstration in downtown Beirut on Oct. 21. (PATRICK BAZ/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

Lebanese women take part in a demonstration in downtown Beirut on Oct. 21. (PATRICK BAZ/AFP/GETTY IMAGES)

In less than a month, demonstrations against corruption and a lack of economic reform erupted in both Iraq and Lebanon. In both countries, the unprecedented protests, which rocked Shiite towns and cities, have revealed that Iran’s system for exerting influence in the region failed. For the Shiite communities in Iraq and Lebanon, Tehran and its proxies have failed to translate military and political victories into a socioeconomic vision; simply put, Iran’s resistance narrative did not put food on the table.

Since the very beginning of the Islamic Revolution, the Iranian government and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have had a clear, long-term, and detailed policy on how to export its revolution to the region, mainly in countries with a substantial Shiite majority. Iran had been very patient and resilient in implementing its policy, accepting small defeats with eyes on the main goal: hegemony over Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen.

Today, Iran seems to be winning the long game. Its proxy in Lebanon prevailed in last year’s parliamentary elections. In Syria, Iran managed to save its ally, President Bashar al-Assad. In the past several years, Iran has also gained a lot more power in Baghdad through its proxies, including the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the Shiite militias created to fight the Islamic State.

However, in its four-decade plan, Iran overlooked an important point: a socioeconomic vision to maintain its support base. While exhausting every opportunity to weave itself into the region’s state institutions, the Iranian regime failed to notice that power requires a vision for the day after. As events unfold in the region, Iran is failing to rule. Iraq and Lebanon are good examples.

Iran created proxies in both countries, gave them power through funding and arms, and helped them infiltrate state institutions. Today, state institutions in Iraq and Lebanon have one main job: Instead of protecting and serving the people, they have to protect and serve Iranian interests.

Observers have called the current protests in Lebanon “unprecedented” for a number of reasons. For the first time in a long time, Lebanese have realized that the enemy is within—it is their own government and political leaders—not an outside occupier or regional influencer. In addition, political leaders have been unable to control the course of the protests, which are taking place across all sects and across all regions, from Tripoli in the north to Tyre and Nabatieh in the south and through Beirut and Saida. The scale shows that the protesters are capable of uniting beyond their sectarian and political affiliations. What brought them together is an ongoing economic crisis that has hurt people from all sects and regions. As one protester said: Hunger has no religion.

For the first time since Hezbollah was formed in the 1980s, Lebanese Shiites are turning against it.

But most significantly, the protests are unprecedented since Hezbollah also took an unusual stance. Having prided itself for decades for protecting the impoverished and fighting injustice, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah decided to side with the authorities against the people in the streets. That’s a major setback for Hezbollah as it deals with the current protests, its most difficult domestic challenge so far.

Hezbollah’s leader did not choose to support Prime Minister Saad Hariri’s government carelessly. Scenes of Shiite protesters joining other Lebanese in the streets terrified the party’s leadership. Lebanon’s Shiites have always been the backbone of Hezbollah’s domestic and regional power. They vote for Hezbollah and its Shiite ally Amal during elections, and they fight with them in Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. In return, many of them receive salaries and services offered abundantly by Iran and Hezbollah.

But for the first time since Hezbollah was formed in the 1980s, Lebanese Shiites are turning against it. In Nabatieh, the group’s heartland in the south of Lebanon, Shiite protesters even burned the offices of Hezbollah’s leaders.

Here, three main factors are at play. First, Hezbollah’s costly involvement in the Syrian war and pressure from U.S. sanctions on Iran have forced the party to cut salaries and services, widening the gap between the rich and the poor within its own community. Meanwhile, the party also drafted mostly Shiites from poor neighborhoods to go fight in Syria, while its officials benefited from the war riches, causing much resentment.

Second, Hezbollah’s constituency was forced to accept Hezbollah ally Nabih Berri as speaker of the parliament as a necessary evil to keep the Shiite coalition intact. Although Berri’s known corruption was at odds with Hezbollah’s narrative of transparency and integrity, the community turned the blind eye for decades. But when Lebanon’s economy started to deteriorate around the same time that Hezbollah’s finances were hit, many Shiites could no longer pay their bills. Berri’s corruption and outrageous wealth could no longer be tolerated.

Third, Hezbollah focused too heavily on military might. It promoted that narrative after Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000 and then again after Lebanon’s July war with Israel in 2006. It also claimed success in Syria against its new enemy—Sunni extremism. However, all these victories failed to translate into public well-being. Iran might have benefited, but Shiites in Lebanon got more isolated than ever. That is why it is so meaningful that the Shiite community, by joining the protests, is now attempting to claim its Lebanese identity rather than the religious one that has, so far, failed it.

Iraqi protestors, almost all Shi’ites, have faced a very violent response from the military and Iranian-back militias.

Iraqi protestors, almost all Shi’ites, have faced a very violent response from the military and Iranian-back militias.

The story is similar in Iraq. This month, tens of thousands of Iraqis in Baghdad and other Shiite-majority parts of southern Iraq came out in protest over the failures of the Iraqi political class to provide basic services and reduce unemployment and corruption. The crackdown was swift and aggressive, resulting in the deaths of more than 100 protesters. Reuters published a story more than a week into the protests confirming that Iran-backed militias had deployed snipers on Baghdad rooftops to deliberately kill protesters.

Iran’s role in responding to the demonstrations in Iraq and the failure of the government to protect its citizens is a significant indication of Tehran’s influence in the country. Many former Iran-backed militia commanders are now members of parliament and the government, advancing Tehran’s agenda and creating an alternative economy for Iran under U.S. sanctions.

Like in Lebanon, Iran’s narrative against the Islamic State helped it get its militia leaders inside the Iraqi parliament and slowly infiltrate state institutions. Like Lebanon’s Hezbollah model, if left unchecked, Iran’s Iraqi proxies will slowly but surely become stronger than the Iraqi Army, and the decision of war and peace will be an Iranian one.

It is no coincidence that only Shiites took to the streets in Iraq. Sunnis have long been oppressed by sectarian and Shiite leaders, and Shiites have not yet broadened their identity to a national one instead of a sectarian one. But there’s a sense that if protests continue, they’ll become more nationwide. Some Sunnis and Kurds in Iraq have expressed support for the Shiite protesters but have hesitated to get involved in order to avoid having the protesters labeled as members of the Islamic State, an excuse that Iran has used in both Iraq and Syria to attack uprisings.

Whatever the protests bring, in both Iraq and Lebanon, Iran will not allow its power structures to crumble without a fight.

In both cases, Iran will do what it does best. In Lebanon, instead of stepping back and allowing reforms to be implemented by new governments with qualified ministers, Hezbollah and the Iran-backed militias will likely resort to force. As Nasrallah made very clear, his government will not fall.

Hezbollah will try not repeat the Iraqi PMF’s mistake of responding with violence. That’s why its military units have been training a number of non-Hezbollah members to join what it calls the Lebanese Resistance Brigades. The role of these brigades is precisely to deal with domestic challenges and allow Hezbollah to deny responsibility. Already, in an attempt to create a counter-revolution, hundreds of young men carrying the flags of Amal and Hezbollah attacked the protesters in a number of cities. So far, the Lebanese Army has stopped them from getting too close to the protests, but they have managed to physically hurt and terrorize people outside Beirut, mainly in Shiite towns and cities.

In Iraq, it is likely that Iran-backed militias will resort to violence again to suppress a new round of protests scheduled for Oct. 25. Without international pressure to dissolve the parliament and force Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi to resign, many people could die. But in any case, Iran’s image will have suffered gravely.

Across the region, the same story is unfolding. Wherever Iran wins, mayhem prevails. From Iraq to Lebanon, it has become clear that Iranian power can no longer be tolerated. And when the country’s own support base can no longer accept Iran as its ruler, the international community needs to take note.

The recent protests show that Iran’s power is more fragile than the world perceives. And more importantly, they should remind that Shiism does not belong to Iran and that maybe it is time to start working directly with Shiite communities.

Hanin Ghaddar is the Friedmann visiting fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy’s Geduld Program on Arab Politics.