UPDATES

The Death of AMIA Prosecutor Alberto Nisman/ An Arab view on Islamism

January 23, 2015

Update from AIJAC

January 23, 2015

Number 01/15 #05

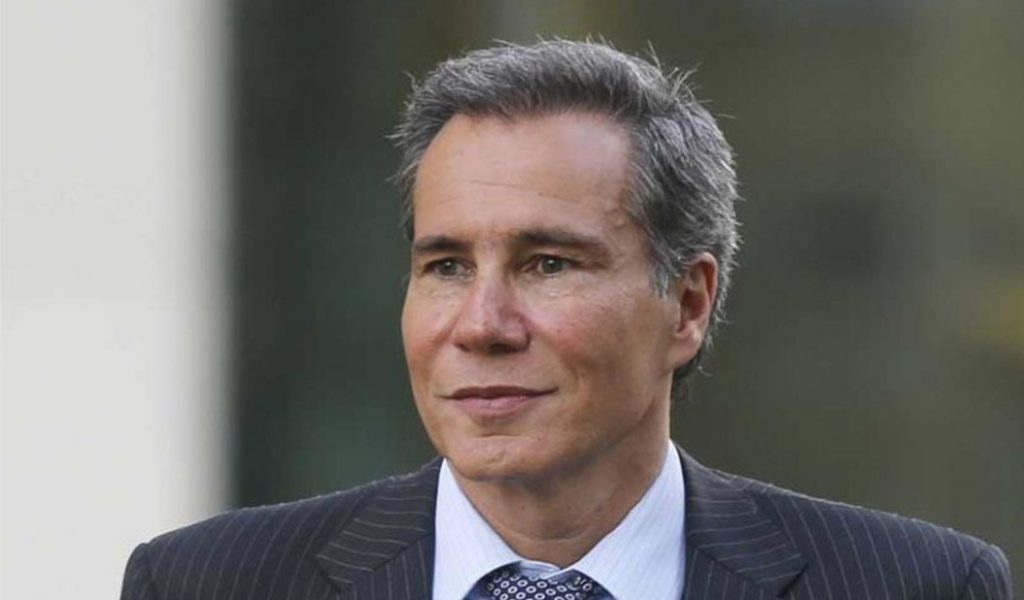

This Update leads with the strange and suspicious death over the weekend of Argentinean prosecutor Alberto Nisman, who has been investigating the 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish centre in Buenos Aires, which killed 85 people, and has lately made dramatic allegations that the current Argentinean government is conspiring to prevent the Iranian culprits from being brought to justice. (These allegations appear to be supported by phone transcripts released by an Argentinean judge following Nisman’s death and summarised in the New York Times here.)

We lead with some comment from top American terrorism expert Matthew Levitt, who knew Nisman fairly well as a result of his research into Hezbollah (which allegedly carried out the AMIA bombing on Iranian orders.) Levitt says he does not believe claims from Argentinean authorities that Nisman committed suicide, and details Nisman’s dogged determination to pursue justice in a case often hindered by corruption and political interference. He details the great amount Nisman accomplished as AMIA prosecutor since 2004 in proving that it was the highest levels of the Iranian regime that ordered the bombing. Levitt concludes, “Today, we are left hoping for closure and justice not only for the victims of the AMIA bombing but for the man who tried more than anyone else to bring them just that.” For this important account of the significance of Nisman’s death from a very knowledgeable source, CLICK HERE. More on the details of what Nisman uncovered from Times of Israel editor David Horovitz – see here and here.

Next up is American columnist Claudia Rosett attempting to draw some wider policy conclusions about Nisman’s work and death – particularly about dealing with the terror networks set up by or sponsored by Iran, including in the Americas. Among the allegations she canvasses is that individuals from the Iranian UN Embassy in New York were found to be engaging in “hostile reconnaissance, photographing ” railroad tracks… subway tracks, bridges and the landing pad of the Wall Street heliport” – presumably as possible sites of future terror attacks. While her policy advice is somewhat US-centric, she offers some important food for thought about coping with Iranian-sponsored terror. To read her discussion in full, CLICK HERE.

Finally, we offer one of the most thoughtful and knowledgeable reflections we have seen on the reality of the threat of violent Islamist ideology and its relationship to the regimes, societies and religious establishments in the Middle East. It comes from Hishan Melham, the Washington bureau chief for Al-Arabiya, the Dubai-based satellite channel. His conclusions are too complex to fully summarise here, but he basically describes a region helpless before a “murderous, fanatical, atavistic Islamist ideology espoused by Salafi Jihadist killers” – with regional governments, moderate Islam, and other institutions all too weak to be an effective counter. It really should be read in full to understand the depth and importance of Melhem’s analysis, and we strongly urge all readers to do so by CLICKING HERE.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Despite earlier asserting Nisman committed suicide, Argentinean President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner now says she believes Nisman was killed.

- In an editorial, the New York Times calls for an ” an international team of jurists” to take up the AMIA case following Nisman’s death.

- Following Nisman’s death, also in Argentina, ten Israeli tourists were wounded in an antisemitic attack on a hostel in which they were staying.

- Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah has died. This was not completely unexpected, but is likely to usher in some uncertainty about the future of the Kingdom – excellent analysis of why and what might happen next has been coming from Washington Institute scholar Simon Henderson over recent weeks – see here and here.

- Following the stabbing attack on a Tel Aviv bus which left 13 commuters injured on Tuesday, Hamas praises the stabber as “heroic”, while Fatah published celebratory cartoons.

- Noted Israeli international law scholar Alan Baker writes to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon calling on him to protect the International Criminal Court (ICC) from politicisation via the Palestinian bid to join and use the body against Israel.

- Isi Leibler writes about Zionism and the plight of French Jews.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Sharyn Mittleman, in an article in the Australian, weighs into the racial hatred law debate in Australia following the Charlie Hebdo attack in France.

- Glen Falkenstein discusses the reluctance to condemn and fight antisemitism in some circles following recent events in France – on ABC’s “The Drum”.

- Allon Lee takes on how the participation of a Palestinian National team in soccer’s Asian Cup has repeatedly been used to spread myths in the media.

Can Argentina Find Justice Without Alberto Nisman?

Matthew Levitt

Foreign Policy, January 22, 2015

The prosecutor investigating a suspected government cover-up of the 1994 AMIA bombing has died suspiciously, sparking mass protests and raising questions about whether anyone else will pursue the case with similar determination.

On Jan. 14, Argentine special prosecutor Alberto Nisman filed a legal complaint formally accusing President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and Foreign Minister Hector Timerman of trying to cover up Iran’s role in in the 1994 bombing of a Jewish cultural center in Buenos Aires that left 85 people dead. Kirchner and Timerman, Nisman claimed, were covering Iran’s tracks in exchange for oil. Four days later, Nisman was found dead in his apartment.

The day after his death, Nisman was supposed to appear before Argentina’s Congress to present new evidence backing up his accusations of Kirchner’s cover-up. Local media reported unnamed sources saying that because a gun was found next to his body and his apartment was locked from the inside, Nisman committed suicide. I don’t believe it.

I knew Alberto Nisman from years researching Hezbollah activities in South America for my book Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God. The idea that he would commit suicide just as the investigation into the 1994 attack is finally making headway simply does not comport with the man and his years-long, dogged commitment to bringing the perpetrators of this horrific act of terrorism to justice. After Nisman filed his complaint last week, Kirchner’s administration insisted the charges “have no foundation,” but neither those charges nor the sudden, suspicious death of the prosecutor who brought them would be the first time the case was marred by political corruption and illegal activities at the highest levels.

Nisman’s latest complaint stemmed from a bilateral deal that Iran and Argentina concluded last year to establish a joint investigation into the blast at the Argentine Israelite Mutual Association (AMIA), which injured more than 150 in addition to killing 85. The Argentinian state investigation into the bombing, led by Nisman, had already concluded in 2006 that Iran and Hezbollah were behind the attack. Since then, Argentine authorities had sought the extradition of eight Iranians for their roles in the bombing, including several senior government, intelligence, and Revolutionary Guard officials. The deal for a joint investigation, it seemed, aimed to reorient the investigation away from Iran in return for improved diplomatic and economic relations between the two countries. Kirchner promised to absolve former Iranian officials accused of masterminding the attack, Nisman charged, in exchange for Iranian oil, possibly at a reduced price. A federal court ruled the bilateral agreement for the joint investigation unconstitutional in May 2014, but an appeal to the country’s supreme court is pending.

From the outset in 1994, before Nisman was assigned to the case, the Argentine investigation into the AMIA attack was handled poorly. Then-Argentine President Nestor Kirchner, the current president’s late husband, would later describe it as “a national disgrace.” The only people convicted of crimes related to the attack were corrupt police officers involved in the sale of the Renault Trafic van that the attackers loaded with explosives. Judge Juan Jose Galeano, who was appointed to serve as chief prosecutor, originally maintained his full caseload while overseeing this major case. Once he took on the AMIA investigation full time, he was caught attempting to bribe a defendant (the defendant himself being an accused corrupt police officer) to falsely accuse other police officers of involvement in the case. This and other “irregularities” — including the charge that Carlos Saul Menem, who was president during the bombing, maintained close ties to Iranian intelligence and accepted a $10 million bribe from Iran to cover up the Islamic Republic’s role in the attack — led a grand jury to impeach Galeano in December 2003 for official misconduct.

At that point, although Galeano had issued his report and handed down indictments, Judge Rodolfo Canicoba Corral took over the case and assigned a team of experienced federal prosecutors to the investigation. Led by Nisman, the team re-investigated the AMIA bombing from scratch, despite the passage of more than a decade since the attack.

Nisman’s single-minded determination to see justice served and bring closure to the victims and their families energized the investigation and produced a thorough, compelling case file pointing to Iran and Hezbollah as the culprits.

The investigation covered hundreds of files, produced 113,600 pages of documentation, leveraged telephone intercepts, and incorporated previously classified material from Argentina’s main intelligence agency. Some of the material prosecutors sought was no longer available, such as financial records destroyed by banks after 10 years, as required by Argentine law. Other information the prosecutors wanted for their investigation was — to their dismay and surprise — never maintained in the first place. Detailed immigration records of the accused bombers and other supporters, which could have shed light on their comings and goings from the country before and after the bombing, were non-existent.

Nisman’s 2006 investigative report concluded that the evidence did not suffice to support the indictment and arrest of some of the individuals fingered by Galeano three years earlier, though he determined that several additional suspects should be indicted. These included Hezbollah’s operational mastermind Imad Mughniyeh, former Iranian President Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and former Revolutionary Guards Corps chief Mohsen Rezaei, among others.

But the prosecutors’ report reserved particular criticism for Galeano’s findings regarding Iran and Hezbollah. While Galeano concluded that the AMIA bombing was the work of “radicalized elements of the Iranian regime,” Nisman’s team determined “that the decision to carry out the attack was made not by a small splinter group of extremist Islamic officials, but was instead a decision that was extensively discussed and was ultimately adopted by a consensus of the highest representatives of the Iranian government.” New indictments were issued and INTERPOL put out “red notices” to facilitate the arrests of the accused.

Given such a definitive conclusion by the government-appointed investigators, the deal between Buenos Aires and Tehran eight years later was always suspect. And it was never clear how Kirchner’s government planned to whitewash the evidence of Iran’s role in the attack, which had been documented in the voluminous investigative files.

With Nisman’s suspicious death, a deal with Iran may no longer be necessary to derail the investigation. Alberto Nisman was a uniquely determined and undeterred prosecutor. Argentine media has responded with rage and incredulity, and Buenos Aires and other cities have seen thousands of protestors take to the streets. Replacing Nisman will be no small feat. And yet, Kirchner’s government now bears the responsibility of doing just that. Nisman’s replacement must be an equally tenacious fighter for truth, and the government must partner with this new prosecutor, not obstruct her or his investigation.

I met Alberto Nisman several times over the years — in my office, around Washington, D.C. over coffee — and each time he was more animated than the last. In our final meeting, he was eager to follow up on leads about Mohsen Rabbani. Rabbani was the accused Iranian mastermind of the AMIA bombing, and his name had come up in a terrorism case in Brooklyn, NY, for which I was an expert witness. I put Nisman in touch with the prosecutors, and he soon left Washington for New York to meet with them.

As I was writing my book, trying to navigate the convoluted details of the AMIA bombing and other Hezbollah plots, Nisman was an invaluable resource. He was a sounding board with whom I could confirm facts and clarify events as I tried to understand what was happening. Soon after Nisman filed his complaint of a cover up, I wrote in an email to some colleagues: “The victims of this horrific attack and their families are still a long way from closure or justice, but the determination of Mr. Nisman — the Eliot Ness of the AMIA conspiracy — should at least give them some measure of hope.”

Today, we are left hoping for closure and justice not only for the victims of the AMIA bombing but for the man who tried more than anyone else to bring them just that.

Matthew Levitt is the Fromer-Wexler Fellow and director of the Stein Program on Counterterrorism and Intelligence at The Washington Institute.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Alberto Nisman’s Warning About Iran

by Claudia Rosett

Forbes.com, 1/20/2015

Beyond puzzling over the circumstances, is there any response the U.S. can make to the sudden death this past weekend of Argentine special prosecutor Alberto Nisman?

Nisman spent the past decade seeking justice for the victims of the 1994 terrorist bombing of a Buenos Aires Jewish community center, which killed 85 people and wounded many more. Nisman compiled a massive case, accusing Iran and its Lebanese terrorist affiliate, Hezbollah, of the attack. He indicted a member of Hezbollah and a number of former high-ranking Iranians officials. And he found himself increasingly at cross-purposes with the machinations of Argentinas President Cristina Kirchner.

Last week, Nisman filed a criminal complaint almost 300 pages long, accusing Kirchner, her foreign minister Hector Timerman, and a number of others, of orchestrating a cover-up of Irans responsibility for the 1994 attack. A summary of the complaint, sent out last week by Nismans office, accused Kirchner of secretly cutting a deal with Iran to concoct a story that would exonerate Iran and its fugitives from the 1994 bombing, thus opening the way for Argentina to trade grain for Iranian oil, at the cost of sacrificing a lengthy and legitimate quest for justice.

Nisman was due to testify Monday to Argentinas Congress about his allegations. He never made it. On the eve of his testimony, the 51-year-old Nisman was found dead in his Buenos Aires apartment, shot in the head.

Argentine officials swiftly declared that Nismans death looked like suicide. Theres plenty of skepticism about that. But with the case under Argentine jurisdiction, there may be little that Americans watching from afar can do. It is telling, perhaps, that even when Nisman was alive, the U.S. couldnt do much on his behalf. In 2013, U.S. lawmakers invited Nisman to come to Washington, to testify about his findings at a House hearing on Threat to the Homeland: Irans extending influence in the Western Hemishere. Nisman wanted to go testify. But Argentinas chief public prosecutor denied him permission, on grounds that it had nothing to do with the mission of the Argentine attorney generals office.

At the hearing, panel chairman Rep. Jeff Duncan expressed his regret that Nisman could not come. Duncan noted that based on information that omitted Nismans findings, the State Department had recently reported that Iranian influence in Latin America and the Caribbean was waning. Duncan added: In stark contrast to the State Departments assessment, Nismans investigation revealed that Iran has infiltrated for decades large regions of Latin America through the establishment of clandestine intelligence stations and is ready to exploit its position to execute terrorist attacks when the Iranian regime decides to do so.

What America can do and should do is pay much closer heed to Nismans urgent warnings. For years, while laboring at an investigation that amassed more than a million pages of documents, he sounded the alarm over Iranian terror networks which he found extended way beyond Argentina and in some cases all the way to the U.S.

Nismans investigation began with the Buenos Aires bombing, also known as the AMIA case (AMIA being the Spanish acronym for the Argentina Israelite Mutual Association). But as he dug deeper, he found that the techniques Iran used to infiltrate agents into Argentina and set the stage for the Buenos Aires attack were part of a network that was replicating itself in such countries as Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile, Suriname, Trinidad & Tobago and Guyana.

The Guyana network had a major link to the man alleged by Nisman to be the main architect on the ground of the Buenos Aires AMIA bombing, the Iranian embassys cultural attache at the time, Mohsen Rabbani. The Guyana network also become involved in a 2007 terrorist plot in the U.S. foiled in time by U.S. authorities to blow up fuel lines and tanks at New Yorks John F. Kennedy Airport. The man in the middle was a former member of the Guyana parliament, Abdul Kadir, who in 2010 was convicted in Brooklyn federal court of conspiring to commit a terrorist attack at JFK Airport, and sentenced to life in prison.

Nisman, in a 2013 indictment, as summarized in English by his office, described Rabbani as an important Iranian agent not only for the AMIA bombing, but as a pivotal figure in a general Iranian scheme of infiltrating Latin-American countries and building local clandestine intelligence stations designed to sponsor, foster and execute terrorist attacks. In detail, citing Iranian officials themselves, Nisman explained how this is part of Irans methods meant to export the Islamic revolution.

Nisman visited the U.S. a number of times during the many years of his investigation, and in March, 2009, I had the first of several chances to interview him in person. We met at a cafe in lower Manhattan. He had just come from talking with New York federal prosecutors about what he described as common concerns in investigating terrorist attacks. He was full of energy; young, dapper, wearing a red and silver tie, with a tie pin. He spoke some English, but was making the rounds with the help of an interpreter. I asked him if he had any worries about his own security. He replied that if he focused on that, he couldnt do his job.

Over coffee, he detailed how the initial investigation into the 1994 AMIA bombing had been a fraud, and when he was assigned to the case in 2004 he had started all over again, working with a team of 40 people. He said that after the first two years of work, they had been able to prove that the attack was organized, perpetrated and paid for by the higher authorities of Iran. The decision to carry out the bombing, he said, was made almost a year before the attack in 1993, in Iran.

He said his investigation had uncovered evidence that back in the 1980s, shortly after Irans 1979 Islamic revolution, Tehrans regime had targeted Argentina as its main point of entry into Latin America. He said there were big two attractions for the Iranian regime: Anti-semitism is part of the culture, and Argentina in those days was willing to provide Iran with some nuclear technology. It was when Argentina, under pressure from the U.S., became less forthcoming on nuclear matters that Iran turned to terrorist attack.

He said that though many Iranians were sent as secret agents, they were assigned to particular ways of life, to settle in. Some were just taxi drivers. Others went to university, especially in medicine. He noted that medicine is a long-term career, and in Argentina, with free education, you could be a student for life. Still others came as businessmen. These businesses did not sell any products, but they had lots of employees he added.

Nisman also warned that when Irans regime is planning operations in a country, it uses the Iranian embassy as a spy center. That may sound unsurprising. But with Iran fielding a large diplomatic mission to the United Nations in New York, as well as a large Iranian Interests Section inside the Pakistan Embassy in Washington, Nismans observation deserves wide attention in the U.S. especially in light of some items in testimony to Congress on March, 2012, by Mitchell D. Silber, former director of intelligence for the New York City Police Department. Silber in his written testimony stated: We believe this is neither an idle nor a new threat. Between 2002 and 2010, the NYPD and federal authorities detected at least six events involving Iranian diplomatic personnel that we struggle to categorize as anything other than hostile reconnaissance of New York City.

Silber then detailed half a dozen episodes involving Iranian diplomatic personnel caught photographing or videotaping railroad tracks inside Grand Central Station, subway tracks, bridges and the landing pad of the Wall Street heliport.

Iran, for its part, has repeatedly denied Nismans allegations, saying it is innocent of any involvement in the 1994 AMIA bombing in Buenos Aires. A typical statement, part of a series, can be found in a letter dated Oct. 6, 2010, from Irans ambassador to the U.N., to the president of the U.N. General Assembly. The ambassador, at some length, denounces Nismans investigation as entirely faulty; then adds that Iran stands ready, nonetheless, to hold a constructive dialogue with the Argentine Government in a spirit of mutual respect in order to develop a clear understanding of each others positions, and seeks to find viable solutions for the misunderstandings arising from this case.

Argentina no longer has Alberto Nisman to testify to what that jargon might mean. But with his courage and years of toil in quest of justice, he has bequeathed us all a warning about where it goes.

Ms. Rosett is journalist-in-residence with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, and heads its Investigative Reporting Project.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

The Time of the Assassins

The Arab world has no counterforce to the murderers in our midst.

By HISHAM MELHEM

Politico, January 09, 2015

There is something malignant in the brittle world the Arab peoples inhabit. A murderous, fanatical, atavistic Islamist ideology espoused by Salafi Jihadist killers is sweeping that world and shaking it to its foundations, and the reverberations are felt in faraway continents. On the day the globalized wrath of these assassins claimed the lives of the Charlie Hebdo twelve in Paris, it almost simultaneously claimed the lives of 38 Yemenis in their capital Sanaa, and an undetermined number of victims in Syria and Iraq. Like the Hydra beast of ancient Greece this malignancy has many heads: al Qaeda, the Islamic State, Sunni Salafists and Shiite fanatics, armies and parties of God and militias of the Mahdi. This monstrous ideology has been terrorizing Arab lands long before it visited New York on 9/11, and its butchers assassinated Arab journalists and intellectuals years before committing the Paris massacre of French journalists, cartoonists and police officers.

The devils rejects of this ideology engage in wanton ritualistic beheadings while intoxicated with shouts of Allahu Akbar, oblivious to the fact that most of their victims are Muslims. They are perpetuating mass killings and rapes, uprooting ancient communities, declaring war on the great pre-Islamic civilizations and religions of the Fertile Crescent, and managing to turn large swaths of Syria and Iraq into earthly provinces of hell.

The time of the assassins is upon us. And the true tragedy of the Arab and Muslim world today is that there is no organized, legitimate counterforce to oppose these murderers, neither one of governments nor of moderate Islam. Nor is there any refuge for those who want to escape the assassins.

Instead, there is only the grim promise of further disintegration. Last year, the area stretching from Beirut on the Med to Basra at the mouth of the Gulf became a long front of Sunni-Shiite bloodletting. The religious and ethnic minorities in the region are cowering with fear and loathing. In this fragmented world, identity politics and parochial loyalties are the powers that move the people. The region is being contested now by the Islamic State and Iran, which is for all intents and purposes a prominent, even if not fully recognized, member of the international coalition fighting the dark forces of the Islamic State. Just think of this surreal scene; Iran the only Shiite theocracy in the region is fighting the Islamic State, the radical claimant of an ephemeral Sunni Caliphate. In 2014 many Arab lands, from Yemen to Libya, oscillated between despair and disintegration. There is no room for moderation or reform or tolerance in theses societies. The weak nation-states are getting weaker and falling apart at the seams. Without reconstituted nation-states there can be no serious societal, political or religious reform.

Along with the disintegration of the states, and deepening sectarian conflicts, the various communities are not only clinging to their identity politics, but becoming more religious, though not necessarily more pious or spiritual. Islamization and attachment to religious symbols, dogmas and rituals are the dominant concerns of many youths, particularly those carrying out the military struggles. The Shiites of Lebanon and Iraq – two states that previously were known for their secular pleasures and rich cultural heritage and vibrancy – are abandoning these traditions. Lively music is shunned and replaced with religious songs, young men wear black and grow beards, and you rarely see uncovered women in most Iraqi and Syrian cities. In Iraq, movie theatres are disappearing in most cities outside Baghdad. Egypt has long since lost the once famed cosmopolitanism of Alexandria to the Salafists. In Lebanon, Hezbollah is turning Beirut into a Tehran on the Med, while the Sunni fundamentalists are turning the country’s second largest city, Tripoli into their own Qandahar on the Med. Can we still talk about reform and moderation to challenge the murderous ideology intellectually?

After the defeat in the 1967 war with Israel, Arab intellectuals, artists, political activists and exiles found themselves drifting towards Beirut, the only Arab equivalent of a shining city on a hill. As a teenager, I witnessed the incredible cultural and political ferment that dominated the debates about the real causes that led the Arabs to such a nadir. I attended debates, watched first-rate theatre, read real soul-searching articles and books. The best and the brightest of Arabs walked and graced the streets of Beirut. Poets, novelists and scholars I read from afar came to partake in the mission of a lifetime. Critical inquiry was the operating principle. That old defiant Beirut made it easier for my generation of Arabs to search and find some answers in those years that preceded the 1973 war, when the defeated Arab regimes were able to claim a partial victory of some sort and to restore the old order. It was a brief moment of hope and enthusiasm.

That is all gone now.

This terrible ideology has grown in the arid political, cultural and economic environment that was created since the Second World War by a weak state system bereft of modern accountable institutions, by praetorian regimes, predatory political classes, reactionary educational systems, and compromised intellectual and religious elites. Western, mainly U.S., support and sponsorship of a number of autocratic Arab regimes which engaged in massive violations of human rights of their peoples as well as occasional military interventions, sometimes with disastrous results, like the invasion of Iraq, have provided this ideology with a veneer of legitimacy in the eyes of its true believers.

After each act of terror, a stunned world – mostly the Western countries – asks: Where are the elusive moderate Muslims? How come they don’t pick up the gauntlet thrown at their faces by the armies of fanaticism? And after each atrocity, many stunned and indignant Arabs who find themselves on the defensive say in disbelief: No true Muslim would do this, and Islam does not condone the killing of innocent civilians. Others are quick to cling to conspiracy theories, blaming a list of convenient villains that includes the United States and Israel where the Central Intelligence Agency and the Mossad are usually ascribed, in imagination, extraordinary powers to perpetuate the destruction of the twin towers and the creation of the Islamic State. Sometimes legitimate questions are asked: Why is it fine and legitimate to lampoon the Prophet Muhammad while it is illegal to deny the Holocaust? But such questions are drowned in the blood that the fanatics spill, when they kill cartoonists and moviemakers because they have insulted the Prophet of Islam.

Muslims should stop living in denial that their religion, like Christianity and Judaism before it, is susceptible to more than one interpretation, and that now it is being distorted by zealots driven by unfathomable political or metaphysical missions. The truth is that the death-embracing ideology we are grappling with, which gave us recently a Caliph whom not even central casting could compete with, has roots deep in our history. It is based on an extreme and fanatical interpretation of the sacred texts that Muslims revered for more than 14 centuries. But Muslims should take solace in the fact that their religion, (this is true also of Christianity and Judaism) was once and for a long time a shining city on a hill. That city had different names throughout history; it was once named Damascus, then Baghdad, then Cairo, then Córdoba then Istanbul . Yet since religion is not the religious text in isolation, but the actual lived experience of the community of the believers, there is always the hope that improved economic and political conditions which restore self-confidence and security can lead to open, tolerant, even progressive interpretations of the religious texts.

When Muslim Córdoba was the jewel of Europe in medieval times, the Muslims there had the same Quran and Hadith as the Islamic State does today.

The killings in Paris comprise the latest chapter in a tragedy that began with the controversy and outrage that surrounded the publication in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten of 12 cartoons of Prophet Muhammad. Arab and Islamic commentary at that time was mostly framed as conspiracy against Islam, a new cultural crusade and with some commentators and religious leaders calling for organizing days of rage. The violent demonstrations in many Muslim majority states, encouraged by religious zealots and professional anti-Western pamphleteers, resulted in the death of scores of people. Few Arab and Islamist commentators framed the issue as one of free expression and pleaded with the Muslim public opinion in Europe and beyond to understand and accept the centrality of the concept of free expression in Europe. Fewer Arabs were willing to accept European criticism of Arab and Muslim double standards when it comes to the publication of anti-Jewish images and cartoons, or the destruction of The Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan by the Taliban.

The initial reaction in the Arab world after the Paris killings was varied with official condemnations from governments and religious institutions like Al-Azhar University in Cairo, and from commentators who denounced it and expressed fear that it could worsen the conditions of Muslim communities in Europe and strengthen the extreme right and Islamophobia in France and the rest of the continent. Ironically, the condemnations of Arab states and Al-Azhar and the League of Arab States of the Paris massacre were swift, compared with the way some of them took their sweet time last summer to denounce the mass killings and the expulsion of the Christian and Yezidi communities in Iraq at the hands of the Islamic State.

However, there were also the usual we condemn, but kind of commentaries expressed on television and written by columnists. France’s (and not surprisingly America’s) policies in the Middle East, including strangely the International coalitions war on the Islamic State, are in part responsible for the attack. Some in the Lebanese media claimed that France was now drinking its own poison, or fighting its own terror, and another theme was to ridicule the idiotic sympathy with France that some Arabs are expressing. One Qatari journalist claimed that France was behind the attack to justify military intervention in Libya, and an Egyptian television commentator proclaimed himself happy with the terror attack because it will force the west to change its approach to [the Islamic State] now that they have seen that terror could reach them.

The problem with condemnations by moderate governments and institutions is that they rarely go beyond words, and they never go to address old stereotypes and long-held negative attitudes towards Western countries or non-Muslim groups, especially when the same governments have been responsible over the years for steering their official media and the intelligentsia beholden to them to direct their wrath against the same parties that now they claim they are supporting.

Of course there are many modern, moderate Arabs who are usually genuinely shocked by these acts of terror, but their expressions of sympathy can do little to change cultural and societal attitudes and assumptions. That is because, once again, these moderate voices do not constitute organized groups, parties or movements capable of engaging in meaningful political activities. Take Egypt for example. Four years after the January Revolution of 2011 that overthrew President Hosni Mubarak, where are the moderate political forces? In these tumultuous years, the country was first under the direct control of the military, which ruled by fiat, then by an elected president, Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood, who did not rule as a moderate or as a democrat when he tried to exclude others, until he was overthrown by the military, which led later to the killings of almost a thousand Egyptian civilian supporters of Morsi in the streets in the bloodiest moment in modern Egyptian history.

The irony was that when the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) was in charge of Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood supported them. After the coup, led by Field Marshal Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi, who later won the presidency, the other Islamist force in the country, the Salafist party al-Nour, threw its support behind the military against the MB. Many of the so-called liberals and secularists, who initially led and organized the uprising that overthrew the Mubarak family, turned out to be totally bereft of the skills and culture to organize themselves as a competitive political movement, but worst still when they established their illiberal tendencies when they turned against the elected president and supported the putsch.

Recently, President el-Sisi made what some have called a dramatic call for a revolution in Islam aimed at adopting modern or reformist interpretations of the faith that would eschew intolerance and violence. But when the leader of a coup against the traditional entrenched Islamist movement in the country poses as an Islamist reformer, one has to wonder why. Clearly, this is an expedient call by a leader who wants to assert his religious bona fides in his ongoing battle with the MB and the other radical Islamist groups waging a campaign of terror against his government. El-Sisi wants to use the conservative Al-Azhar, which depends on the financial sponsorship of the Egyptian government for its sustenance, to lead the campaign. But the last thing the Egyptian president, who has been waging his own campaign of intimidation against Egyptian civil society, activists of all stripes, local and foreign journalists and international NGOs, is to really empower an Egyptian institution.

Can El-Sisi afford an independent Al-Azhar questioning not only the violence of the terrorists, but also the violence of the state that he controls, in the form of torture, arbitrary arrests and subtle and not so subtle intimidation of reformers? This episode should put to rest any hope by anyone who believes that officially sanctioned religious institutions like Al-Azhar in these undemocratic states can initiate meaningful religious reform, or engage in open and serious religious discourse, knowing full well that such discourse will lead inevitably to open political discourse. The reality is that there is not in the Sunni Arab world one single religious institution that is not controlled or sponsored by its government and which is therefore illegitimate in the eyes of the people.

Western politicians and scholars anticipating or asking for meaningful political and religious reforms by the non-existent organized moderates in today’s Arab world will be better advised to be patient and bid their time. Can those living in Baghdad, Aleppo, Sanaa, and Tripoli – just to name few Arab cities – be blamed if they were not shocked by the killing of the Charlie Hebdo twelve in Paris? Not is only Islam’s religious text being distorted, a whole Arab generation has been totally desensitized by unspeakable violence. More than 76,000 Syrians were killed in 2014, making it the deadliest since the beginning of the uprising. In Iraq an average of 1,000 people were killed each month last year. No one has a clear idea about the number of the maimed and the missing, and of those uprooted, and those being claimed by the waves of the Mediterranean while sailing aimlessly seeking a foreign shelter. Counting the numbers of dead and wounded in those countries that went through the baptisms of uprisings is too grim a task.

The tragedy of the Arabs circa 2015 is that they no longer have institutions that can save them from the murderers, just as they no longer have a Beirut that will embrace them and give them intellectual sustenance and a fleeting chance to engage in introspection after an atrocity like the one in Paris, to ask themselves the hard questions that only they can pose and answer. Alas, the old Beirut is no more, just as the old Alexandria is no more. We are left with the faded memories and lamentations of a world that cannot be restored any time soon. It is indeed the time of the assassins, and they are, for now, unopposed by their own people.

Hisham Melhem is the Washington bureau chief of Al-Arabiya, the Dubai-based satellite channel. He is also the correspondent for An-Nahar, the leading Lebanese daily.

Tags: Iran