UPDATES

Israeli election results appear to be surprisingly strong win to Netanyahu’s Likud

March 18, 2015

Update from AIJAC

March 18, 2015

Number 03/15 #03

With more than 99% of the vote now counted, the Israeli election, which occurred yesterday Israel time (meaning overnight Australia time) has led to a resounding victory for incumbent Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and his Likud party. This is a surprise – contrasting not only with the polls of recent weeks, which suggested the opposition Zionist Camp party was somewhat ahead, but even the exit polls from yesterday, which showed the two largest parties virtually neck and neck.

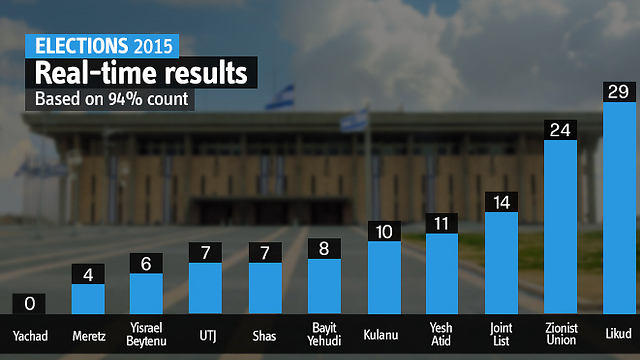

Here are what look like the latest results, in graphic form, as of this afternoon, Australia time:

(They have since adjusted only slightly with Likud picking up one more seat, bringing its total to 30, and UTJ losing a seat, now down to six.)

AIJAC’s Ahron Shapiro has published some good analysis of what the election results means in terms of the balance of the right versus left blocs in Israel (its not a triumph for the right as some in the media are reporting). Plus, in a separate blog Shapiro also explains the context for a widely-reported comment Netanyahu made Monday which seemed to rule out a Palestinian state (in context it is clear Netanyahu meant Palestinian statehood was not possible in the immediate future because of the threat from Islamists, but he was not ruling it out for the longer-term.)

We offer some additional preliminary reports and analysis below.

First up is the report on the results from the Times of Israel, noting the different landscape this morning – much more favourable to the Likud – compared to what exist polls indicated last night at the close of voting, with Likud apparently now expected to have a 5 seat lead over the Zionist Camp, 29 seats to 24 (this was written before the latest adjustment). It also discusses where the process is likely to go from here and the history of this campaign. The story also notes that Netanyahu’s success does seem to result in part from more nationalistic rhetoric, warning of the dangers of a left-wing government, which helped draw in some voters from parties to the right of the Likud. For the full story, CLICK HERE.

Next is Israeli blogger Shmuel Rosner, who explains what difference that latest results mean when compared to what the exit polls were showing last night. Updating an analysis he made last night based on the exist polling, Rosner notes that the likelihood of a national unity government now seems to have fallen dramatically and Netanyahu now has a much clearer path to a narrow centre-right-religious coalition of at least 66 seats out of the 120 in the Knesset. He also notes that Zionist Camp leader Isaac Herzog’s achievement in raising the vote of his party now look much less impressive than it did, while the ability of former communication minister Moshe Kahlon and his centrist Kulanu faction to play kingmaker has also been curtailed by Netanyahu’s apparently much stronger postion. For this important analysis of the implications of the latest results, CLICK HERE.

Finally, we offer a piece written before the poll by Italian-born expert and think-tanker , who attempts to put the election into historical context. He notes that many pundits like to speculate on major political earthquakes resulting from elections, but a major change in Israeli policy was never likely from this poll, no matter who won. He explains that there is actually less polarisation in Israel than in the past on major foreign policy issues, and the reality is that, despite the frequently heard claims that Israel has “moves to the right” in recent years, in fact “if many voters moved to the right, in other words, it is also because right-wing politicians have met them halfway in the center.” For this important effort to put the election in perspective, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Despite the fact that a national unity is looking increasingly unlikely, some are still calling for it – including a Jerusalem Post editorial, and veteran journalist and AIR Israel correspondent Amotz Asa-El.

- Israeli election day in pictures.

- Gerald Steinberg in a pre-election piece on why the ruling Likud party is looking dysfunctiona l as a party despite their electoral success.

- In addition to Ahron’s two stories above, some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- Colin Rubenstein in the Canberra Times on the dangerous gamble being pursued in the nuclear negotiations with Iran.

- Glen Falkenstein responds to recent comments on ABC-TV “Q&A” by actress Miriam Margolyes blaming Israel for the rise of antisemitism.

Netanyahu scores crushing victory in Israeli elections

With almost all votes tallied, Likud heading for 29-24 seat win over Zionist Union; PM promises new coalition with other nationalist parties

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party was the clear winner in Tuesdays election, a near-final tally showed early Wednesday morning, defeating the Zionist Union by a margin of some six seats.

That margin was far more decisive than TV exit polls had predicted when polling booths closed at 10 p.m. on Tuesday. All three TV polls had put Likud and Zionist Union neck-and-neck at 27 seats, albeit with Netanyahu better-placed to form a coalition.

On the basis of those TV polls, Netanyahu hailed a Likud victory, though Herzog refused to concede. As counting proceeded through the night, however, the Likud opened a growing margin of victory.

By 5 a.m., with some 90% of votes counted, the Central Elections Committee was indicating a dramatic victory for Netanyahu, with the Likud heading for 29 seats, compared to Zionist Unions 24 seats.

Next came the Joint (Arab) List on 14 seats, Yesh Atid on 11, Kulanu on 10 and the Jewish Home on 8. They were followed by Shas, 7, United Torah Judaism on 6, Yisrael Beytenu on 6, and Meretz on 5 seats.

Four hours earlier, at 1 a.m., Netanyahu claimed a victory against all odds and promised to form a new government without delay. But Herzog also said he would make every effort to build a coalition. Either will likely need the support of Moshe Kahlon of the Kulanu party, whose campaign focused almost entirely on bread-and-butter economic issues, refused to take sides, but he is a former Likud minister.

As the exit poll results were announced on the nations three major TV stations, celebrations erupted at Likuds campaign headquarters in Tel Aviv. Against all odds we obtained a great victory for the Likud, Netanyahu told the gathering. Now we must form a strong and stable government that will ensure Israels security and welfare, he added, in comments aimed at Kahlon.

He said he had already been in touch with all other nationalist parties in hopes of quickly forming a coalition apparently ruling out a partnership with Herzog.

Netanyahu focused his campaign on security issues, while his opponents instead pledged to address the countrys high cost of living and accused the prime minister of being out of touch with everyday people. Herzog also promised to repair tattered ties with the US and to revive peace efforts with the Palestinians.

Herzog said he too had reached out to potential coalition partners. In a nod to Kahlon, he said he was committed to forming a real social reconciliation government committed to lowering the cost of living and reducing gaps between rich and poor.

Netanyahu’s return to power would likely spell trouble for Mideast peace efforts and could further escalate tensions with the United States.

Netanyahu, who already has a testy relationship with US President Barack Obama, took a sharp turn to the right in the final days of the campaign, staking out a series of hard-line positions that will put him at odds with the international community.

In a dramatic policy reversal, he said he now opposes the creation of a Palestinian state a key policy goal of the White House and the international community. He also promised to expand construction in Jewish areas of East Jerusalem, the section of the city claimed by the Palestinians as their capital.

Netanyahu infuriated the White House early this month when he delivered a speech to the US Congress criticizing an emerging nuclear deal with Iran. The speech was arranged with Republican leaders and not coordinated with the White House ahead of time.

In Washington, White House spokesman Josh Earnest said Obama was confident strong US-Israeli ties would endure far beyond the election regardless of the victor.

The process of building a government, nonetheless, will depend on the final results, as well as on whom the various party leaders recommend that President Reuven Rivlin entrust with the opportunity to form a coalition.

Vote counting was continuing through the night, with more conclusive figures expected in the coming hours. The Central Elections Committee published real-time counting results on its website (Hebrew).

The exit polls, conducted by Israels three main television stations, showed Likud at 27-28 seats and Zionist Union at 27.

Netanyahu called the result a great victory for the Likud. A major victory for the people of Israel.

In the TV polls, potential Likud ally Naftali Bennetts right-wing Jewish Home was heading for eight-nine seats, and Avigdor Libermans nationalist Yisrael Beytenu was set for five seats. Together with the two ultra-Orthodox parties Shas, which was expected to win seven seats, and the United Torah Judaism, which was heading for six-seven seats this could give Netanyahu the firm basis for a right-wing/Orthodox coalition. If Netanyahu can bring in Kulanu, that mix would give him a narrow majority in the 120-seat Knesset.

On the other side of the aisle, Herzog’s natural ally, the left-wing Meretz party, was headed for five seats, while the centrist Yesh Atid was set to win 11-12 seats. Even with support inside or outside a coalition from the Arab Joint List, which looked set to score an impressive 12-13 seats, that would leave Herzog far short of a majority. Kahlons support, were it forthcoming, could conceivably give Herzog a blocking majority, but this scenario seemed highly implausible.

The election was initiated more than two years ahead of schedule by Netanyahu, who fired his finance minister Yair Lapid and justice minister Tzipi Livni in early December.

The campaign was largely seen as a referendum on the Likud leader, who is Israels second-longest-serving prime minister, having held the job since 2009 after a previous term in 1996-9.

On election day itself, Netanyahu repeatedly protested what he said was foreign funding that was helping to get out the Arab vote, and potentially skewing the elections. There is nothing illegitimate with citizens voting, Jewish or Arab, as they see fit, he said on Tuesday afternoon. What is not legitimate is the funding - the fact that money comes from abroad from NGOs and foreign governments, brings them en masse to the ballot box in an organized fashion, in favor of the left, gives undue power to the extremist Arab list, and weakens the right bloc in such a way that we will be unable to build a government despite the fact that most citizens of Israel support the national camp and support me as the prime minister from Likud.

He also castigated the leader of the Joint List: ”Ayman Odeh, who supports Herzog, has already said not only that I must be replaced, but that I should be put in prison for defending the citizens of Israel and the lives of IDF soldiers [during last summers Gaza war] . A left government that depends on such a list will surrender at every step, on Jerusalem, the 1967 lines, on everything,” Netanyahu railed, and therefore there’s an immense effort of leftist NGOs to mobilize voters from the left bloc, primarily in the Arab sector, and in areas where leftists vote.

Netanyahu’s increasingly hawkish statements underpinned his successful effort to dissuade right-wing Israelis from voting for parties other than Likud, gathering steam as opinion polls in the run-up to Tuesdays vote showed Herzog gradually opening a three-to-four seat lead.

The Zionist Union leader, son of the late Israeli president Chaim Herzog and the grandson of Israels first chief rabbi, fought a fairly effective campaign, partnering his Labor party with Livni’s Hatnua and focusing on the socioeconomic issues that are high on many Israelis lists of prime concerns. He blamed Netanyahu for soaring house prices and for the relatively high overall cost of living and branded Netanyahu as out of touch with the day-to-day concerns of ordinary Israelis.

Herzog, like the prime minister, stressed the imperative of preventing Iran from attaining nuclear weapons, though he argued against Netanyahu’s speech to Congress. And he took a wary stance on the Palestinian issue - firmly backing a two-state solution and declaring a readiness to evacuate isolated West Bank settlements, but also vowing to keep Jerusalem united and to seek sovereignty over major settlement blocs. In this respect, he reflected the stances of some of Labor’s more hawkish past leaders, such as the assassinated prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, in a bid to avoid alienating potential voters from the center of the spectrum.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

The morning after the elections: Things that I need to take back

Yesterday evening, when the exit polls showed a tie (or a near tie) and a possible Netanyahu coalition of 63 or 64 seats - that is to say, a very narrow coalition - one could still see a path to a unity coalition. Today, with the results showing a much wider gap in favor of Likud, and a path to a somewhat wider coalition, a unity government is harder to imagine.

Likud activists were quite clear in expressing their feelings regarding unity last night, when Netanyahu was on stage speaking and they all chanted we dont want unity. Labor Knesset Members also had reservations. They are here for the long run, one of them said namely, lets stay in the opposition in hope that we can make it next time.

So the President might still want unity. But I dont think he can achieve such a goal at the moment.

2. Coalition? simple!

Last night because of the exit polls (Ill get to the polls later) we thought that a Netanyahu coalition would have to be very narrow. Thats not exactly the case this morning. He can have a coalition of 66 (it can still be 70 if the Yachad Party ends up edging in, or 67 if UTJ gets 7 seats and not just 6). Netanyahu still has a problem: he essentially needs every party on the list of wannabe members of the coalition and every such party can dismantle the coalition for whatever reason. That is, this coalition will only be as strong as its weakest link, and Netanyahu will only be strong if his partners fear another election more than he does.

3. Herzog a winner?

Not quite. Yesterday it seemed as if he achieved something by making Labor a player and gaining seats. Today the picture is a little different. Labor and Hatnua had a combined number of 21 seats in the outgoing Knesset. The Zionist Camp is at 24. More seats, but not by much. This opens the door for other Labor members to consider a move against Herzog the Labor Party is known for not being able to stick with a leader for more than one term.

4. Lapid? Loser

Lapid and his Yesh Atid Party lost 8 seats and is going to be an opposition party and not even the main opposition party. Its members are going to get bored, they are going to get frustrated when they see the Haredi parties dismantle the laws they were able to pass with the outgoing government. It is going to be a real test for Lapid.

5. Kahlon the king maker?

Yes and no. Netanyahu does not have a coalition without him but there is no coalition that does not have Netanyahu as its head. So Kahlon can make demands, but his cards are limited. If because of him Israel has to go to the polls again, the voters might not like it. In fact, the cards Kahlon holds are not much better than the cards held by Avigdor Lieberman. Netanyahu needs both of them and both of them have no alternative to Netanyahu except for sending Israel to a new election.

6. Bennetts problem

Naftali Bennet is in trouble. His voters decided to vote for Likud and make sure the camp wins, while others flocked to Eli Yishai and had no impact (unless he passes at the last minute). This could mean a need to rethink the strategy of Habit Hayehudi – it could mean the end to Bennetts dominance.

7. Livni will not be a minister

To break the record and be a minister representing four different parties (Likud, Kadima, Hatnua, Labor) shell need to wait for a Labor victory next time, or to form yet another party or join yet another party. I wonder if Labor is going to reserve a seat for her for the next round. I bet she wonders about that too.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

A House Undivided: Israel’s New Consensus Politics

The American Interest, March 16, 2015

Israelis go to the polls on March 17, and in a time-honored tradition, international pundits are hoping for a political earthquake. This ballot, they say, will finally and completely determine whether Israel ever makes peace with the Palestinians, whether its inter-communal tension will devolve into civil war and whether it can stop an Iranian nuclear bomb before it is too late. However, it is likely that, like most of Israel’s preceding elections, this one will bring incremental rather than apocalyptic change, and Israels domestic, regional and foreign situation will remain largely the same as it had been before.

This is not to say that Israeli elections are inconsequential. The rise of Menachem Begin and his Likud party to power in 1977 brought an end to five and a half decades of Labor-movement dominance before and after Israel’s independence.

The 1977 upset known to Israelis as the Maapach, or upheaval inaugurated a 24-year period of competition between left and right, where right-of-center coalitions battled with their left-of-center counterparts, and during a six-year stalemate, had to cohabit under grand coalitions aptly named national-unity governments.

The coalition dynamics of that period may appear preferable to the current proliferation of personality cults, short-lived splinter parties and ad-hoc alliances, but it also reflects greater polarization within Israeli politics than at present. During that era, Israel witnessed the rise of the settlement movement and its polar opposite, Peace Now; it launched the 1982 Lebanon War, survived a financial crisis and hyperinflation; and confronted the First Palestinian Intifada, or uprising (1987-1993).

The 1992 elections restored Labor to power and ushered in direct negotiations between Israel’s Labor-led coalition and the Palestinian Liberation Organization. The issue was so divisive, however, that it dominated elections in the 1990s to the exclusion of other issues. Israel lived through the drama of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination and, in what became known as the Second Intifada, suffered through the first wave of mass suicide terror attacks inside its population centers.

Ultimately, the Oslo Accords peace dividends were elusive. The traumatic impact of the Second Intifada still accompanies Israels collective psyche, and the 2001 and 2003 elections delivered a sound defeat to the pro-Oslo leadership. The collapse of negotiations and the Second Intifada undid Israel’s left but did not move Israel to the right. In fact, the dynamics of Israeli politics have since had one constant element in common gravitation towards the political center.

The prevalence of right-of-center politicians and coalitions is deceptive. For starters, Israelis have reached a near wall-to-wall consensus on the enormity of the Iranian nuclear threat. Netanyahus Bar-Ilan speech in 2009where he grudgingly accepted the notion of a Palestinian statereads almost like the Labor platform that carried Rabin to victory in 1992 and formed the prelude to the Oslo process. If many voters moved to the right, in other words, it is also because right-wing politicians have met them halfway in the center.

A victory for the left-of-center alliance of ex-ministers Tzipi Livni and Isaac Herzog may change some, but not all, of the parameters of Israels regional and foreign policy. Some of their likely partnersthe Yesh Atid party of the former celebrity newscaster Yair Lapid, Kulanu of ex-Likud minister Moshe Kahlon, and at least one religious party are the same interlocutors that Netanyahu would court in his own efforts to form a coalition.

New parties have risen, triumphed, and disintegrated so quickly that it is hard to keep track of mergers and splinters. Despite the erosion of support for both Likud and Labor, Israeli politics have developed around a new national consensus that wants cautious leaders to navigate the geostrategic horizon prudently. Israelis are keen to reach a compromise with the Palestinians but despair of having one given ongoing Palestinian incitement and terror, the presence of Iranian proxies at Israel’s borders, and regional turmoil left unchecked by a retreating American superpower.

Increasingly, Israelis regard more ideological proponents of the settlements project with suspicion, but are loath to renounce strategic settlement blocs and the Jordan Valley to a Palestinian society increasingly dominated by Islamic extremists. Crucially, they have little faith in the Palestinian Authority’s ability to prevent a West Bank a replay of the scenario that followed the withdrawal from the Gaza Strip ten years ago with thousands of rockets indiscriminately launched at its civilian centers. That is why, ultimately, whoever wins will have to embrace that consensus and govern from the center.

There’s the rub. Those who view Israels elections as a clash of titans on which the fate of Zionism depends fail to see how stable the Israeli political system is. The truth is less exciting and more mundane.

The upcoming elections are unlikely to usher in another upheaval. A victory for either the Likud or Herzog-Livni camps will more likely occur by the thinnest of margins, and will have to rely on a broad coalition of centrists and possibly religious parties to keep afloat. Gone are the days when Labor or Likud could, alone, win at least a third of Knesset seats. Whoever emerges victorious will have to strike deals with the plethora of small parties occupying Israel’s center, while accommodating their natural allies to their right and left.

Emanuele Ottolenghi is a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies

Tags: Israel