UPDATES

Islamism and the Arab Spring

November 11, 2011

Update from AIJAC

November 11, 2011

Number 11/11 #03

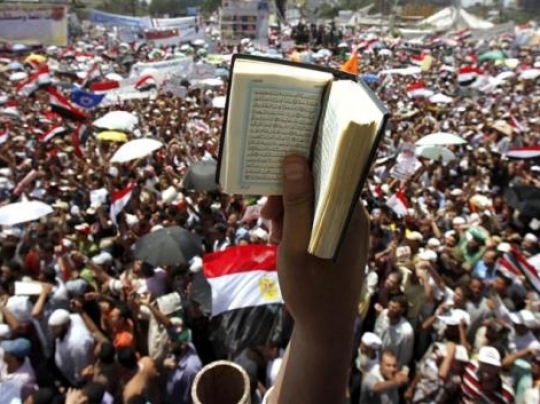

This Updates features three informative pieces on the seemingly increasingly Islamist tint colouring the Arab Spring movements, from Tunisia, to Libya, to Egypt, and beyond.

First up is one of Israel’s most respected and sober Middle East experts, Dr. Asher Susser from Tel Aviv University. He takes issue with the way the media and commentators have focussed too heavily on the “computer-savvy younger generation, skilled in the social networking tools of Facebook and Twitter and the modern media” which were allowed to overshadow the vast strength of the forces of tradition in Arab society. He argues that it is actually secularism that is in crisis across the Arab world, and the Arab Spring has “in many ways become a launching pad for Islamist political ascendance” with unclear effects on democracy hopes. For these important thoughts from a very knowledgeable source,

CLICK HERE.

Next up is another distinguished Israeli academic, noted historian Benny Morris. Using concrete examples from various countries, he concludes with Susser that “the main result of the ‘Arab Spring’ will be—at least in the short and medium terms, and, I fear, in the long-term as well—an accelerated Islamization of the Arab world.” And goes on to make the case that this trend means more regional violence, especially against Israel and problematic and severely altered Muslim-Western relations. For all that he has to say, CLICK HERE.

Finally, noted international affairs correspondent Bret Stephens examines why Islamism remains so attractive as a political philosophy across the Middle East. To answer this, he reviews the history of various other movements across the region – socialism, pan-Arabism, national socialism, secularism, and liberalism, and how they are all viewed as having failed to live up to expectations, and helped entrench various forms of corruption and tyranny. He predicts it could be thirty years or more until the disenchantment with Islamism which has taken hold today in Iran, following the 1979 revolution, spreads to other Middle Eastern nations. For the rest of his analysis, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Barry Rubin explains why many attempts to explain away the possibility of an Islamist takeover of the Middle East are based on wishful thinking and factual inaccuracy.

- Author Lee Smith contends that a “Muslim Brotherhood Crescent” is appearing from Tunisia to Gaza.

- Leading US Republican Presidential candidate Mitt Romney calls for firmer action on Iran’s nuclear program in an op/ed.

- American columnist David Ignatius suggests that the Arab Spring changes may possibly cause a re-orientation of Hamas. Plus another report on dwindling Hamas popularity in Gaza.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- In the wake of some unpleasant private words from US President Obama and French President Sarkozy, I ask “Is Bibi getting a bum rap?”

- Following the IAEA report on Iran, Iran responds by threatening to attack Israel – again.

- A UN report on the Palestinian statehood bin shows UN cognitive dissonance over the proposal given that the Palestinians clearly do not currently meet the normal criteria for statehood.

Tradition and Modernity in the “Arab Spring”

Asher Susser

Tel Aviv Notes,

Volume 5, Number 21

November 10, 2011

The upheavals spanning much of the Arab world over the last year have introduced dramatic change in the region, overthrowing leaders in some countries and seriously destabilizing regimes in others. The recent level of popular participation in Arab politics has been unprecedented, as masses of people have vented their anger in protracted struggles against the oppressive regimes that have ruled over them for decades. After more than two centuries of westernizing modernization, Arab societies in the non-oil-producing countries face profound economic crises with huge younger generations confronting a dire and depressing future of unemployment and poverty. Thus, the disempowered and the dispossessed have risen up against the alliance of tyranny and corruption in Middle Eastern societies, yearning like all peoples of the modern world for the universal values of freedom, justice and prosperity.

In this crisis the computer-savvy younger generation, skilled in the social networking tools of Facebook and Twitter and the modern media, especially the plethora of satellite TV stations, mobilized the masses and magnified and multiplied the impact of their struggle to great effect. The region is unquestionably experiencing a variant of revolutionary change in many places, through novel forms of political struggle, enhanced by the marvels of cutting-edge technology of the modern age.

Yet, at one and the same time, in this era of novelty, innovation, popular participation and revolutionary change, the mystique of ultra-modern high-tech has been allowed by many observers to overshadow the forces of tradition that continue to dominate Arab societies. Virtual reality and influence in cyber-space have been confused with real political power, as the leaderless mass movements that have produced neither coherent political platforms nor well-articulated policies have encountered great difficulty in transforming virtual influence into tangible political strength. Other, more traditional, better organized and more ideologically coherent forces in Middle Eastern politics, such as the Islamists on the one hand, and the military on the other, have been more adept in seizing the reins of actual power in the wake of the regional turmoil.

The modernization, westernization and secularization that the Middle East has undergone in the last two centuries has not been a linear progression, and in recent generations they have been seriously curtailed and even set back. Secularism is in crisis, if not retreat, as Middle Eastern societies become ever more “secular-religious,” to borrow a term from Asef Bayat. Arabism was not only an ideology that promoted Arab unity, it was a platform for secular and secularizing politics. After all, the cohesive element of Arabism was not religion but language, which united rather than divided Arab Muslims and Christians. But Arabism, despite its initial promise, was a dismal failure. It never delivered the political or economic success that the Arabs across the Middle East had hoped for. The march towards Arab unity, coupled with Arab socialism and an alliance with the Soviet Union proved to be a false messiah.

The ideological vacuum left in the wake of the failure of Arabism has been filled largely by resurgent Islamist politics. The concurrent decline in the regional clout of formerly leading Arab states like Egypt, Syria, and Iraq has been countered to a large degree by the burgeoning influence of non-Arab Middle Eastern powers like Turkey and Iran. Both of these rising regional forces offer models of emulation that are hardly secular. Turkey of the conservative Islamist Justice and Development Party, though still functioning more or less in accordance with Turkey’s secular constitution, is a far cry from the purist secularist model of the republic founded by Kemal Atatürk in the early 1920s. Iran of the Ayatollahs, needless to say, is nothing of the kind either.

In a Middle East where secularism is in retreat, interstate relations are no longer a function of great power politics or contrasting forms of government, with monarchies pitted against republics, but have instead become the domain of religious sectarianism, with Sunni Muslim states aligned against their Shi`ite competitors. If that is true in interstate relations, it is even more so in domestic politics, where traditionalism, or neo-traditionalism, have resurfaced as the dominant forces of Arabism and Arab states have lost so much of their erstwhile ‘stateness’, vitality and popular appeal. Islamist politics, religious sectarianism and tribalism have filled the void.

Looking across the region, from country to country, this trend is readily apparent. In Tunisia, the Islamist al-Nahda Party has just won the first elections in the post-revolutionary era. In Egypt, the Muslim Brethren and more radical Islamists, like the Salafists and al-Gama`a al-Islamiyya are poised to perform well in the forthcoming elections. If the referendum held last March in Egypt is any indication of what is to come, the Islamists are virtually in the driver’s seat of post-Mubarak Egyptian politics. Syria has turned into a sectarian bloodbath where the Alawi–dominated regime is fighting for its life in a ruthless struggle against its opponents from the ranks of the dispossessed Sunni majority. Iraq, though unrelated to the “Arab Spring,” has become the scene of ultra-sectarian politics in a new post-Saddam, Shi`ite-controlled country in which the erstwhile Sunni masters of the land have been systematically driven to the margins. In Bahrain it was the downtrodden Shi`ite majority that rose in rebellion against their Sunni rulers, only to be put down violently with the help of Bahrain’s Sunni allies in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. They could not bear the thought that Bahrain might turn into a Shi`ite-dominated Iranian bridgehead on their doorstep. Politics in Libya and Yemen are largely tribal affairs, coupled in both cases with strong Islamist undertones.

With the Islamists so well placed in the countries that are en route to more pluralist political systems, the question arises if Islamism and democracy are necessarily mutually exclusive. The answer is no, provided that the Islamists prove to be willing to accept four key interrelated principles: the non-application of the Shari`a as the legal system and the acceptance of its secondary status to the legislation of a democratically elected legislature; the full and unhindered equality of all religious minorities; the complete and uninhibited equality of women; and the unequivocal acceptance of the principles of freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the freedom of, and from religious belief. All democracies rest on the fundamental principle of the sovereignty of man. There can be no compromise between the sovereignty of man and the sovereignty of God. In a democracy, there can be no substitute for the free election of men and women to a legislature that provides a system of man-made laws for the governed. A legal system like the Shari`a (or the Jewish Halakha, for that matter), which is deemed as God-given, might be fair and just, but democratic it is not, simply by virtue of the fact that it is not the making of the elected legislature, and its source of authority is God Almighty and not the people.

The so-called “Arab Spring” has in many ways become a launching pad for Islamist political ascendance. Whether that means more, or less, democracy, only time will tell, but the present is shrouded in doubt and skepticism.

Prof. Asher Susser is a senior research fellow and former director of the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Arab Spring or Islamist Surge?

Benny Morris

The National Interest, November 3

Rioting in Tunisia and Egypt in early 2011 unleashed a tidal wave of unrest across the Arab world that was soon designated the “Arab Spring.” Enthusiasts in the West hailed a new birth of freedom for a giant slice of humanity that has been living in despotic darkness for centuries. But historians in fifty or a hundred years may well point to the 1979 events in Teheran—the Islamist revolution that toppled the Shah—as the real trigger of this so-called “spring” (which is looking more and more like a deep, forbidding winter). And the Islamist Hamas victory in the Palestinian general elections of 2006 and that organization’s armed takeover of the Gaza Strip the following year probably signified further milestones on the same path.

For, if nothing else, the past weeks’ developments have driven home one message: That the main result of the “Arab Spring” will be—at least in the short and medium terms, and, I fear, in the long-term as well—an accelerated Islamization of the Arab world. In the Mashreq—the eastern Arab lands, including Saudi Arabia, Syria and Iraq—the jury may still be out (though recent events in Palestine and Jordan are not encouraging). But in the Maghreb—the western Arab lands, from Egypt to the Atlantic coast—the direction of development is crystal clear.

In Tunisia the Islamist al-Nahda (Ennahda) Party won a clear victory in the country’s first free elections, winning some 90 out of 217 seats in the special assembly which in the coming months is to chart the country’s political future. Speculation about whether the party is genuinely “moderate” Islamist—as its leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, insists—or fundamentally intent on imposing sharia religious law over Tunisia through a process of creeping Islamisation a la the Gaza Strip and Turkey is immaterial. The Islamists won, hands down and against all initial expectations—and in a country that was thought to be the most secular and “Western” in the Arab world. Freedom of thought and religious freedom are not exactly foundations of Islamist thinking, and whether Tunisian “democracy” will survive this election is anyone’s guess.

To the east, in the tribal wreckage that is Libya, the Islamist factions appear to be the major force emerging from the demise of the Qaddafi regime. In the coming weeks and months we are likely to see movement toward elections that will hammer down another Islamist victory.

And much the same appears to be emerging from the far more significant upheaval in Libya’s eastern neighbor, Egypt, with its 90 million inhabitants—the deomographic, cultural and political center of the Arab world and its weather vane. The recent crackdown, by a Muslim mob and then the ruling military, against Coptic Christian demonstrators (protesting the destruction of a church) was only, I fear, a taste of things to come. All opinion polls predict that the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood—which has long sought the imposition of strict sharia law and Israel’s destruction—will emerge from next month’s parliamentary elections as the country’s strongest political party, perhaps even with an outright majority. An Islamist may well win the presidential elections that are scheduled to follow, if the army allows them to go forward.

And the Sinai Peninsula bordering Israel and the Gaza Strip has become, following Mubarak’s fall, a lawless, Islamist-dominated territory. Egyptian writ runs (barely) only in the northeastern (El Arish-Rafah) and southeastern (Sharm a-Sheikh) fringes. The peninsula’s interior is in the grip of Islamists and bedouin gunmen and smugglers and has become a major staging post for Iranian arms smuggling into the Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip.

For months now the Egyptian natural gas pipeline to Israel (and Jordan) has been cut, the military unable to prevent continued incidents of Islamist-beduin sabotage. The severance of the gas export—in effect, a continuing Egyptian violation of an international commercial agreement—has meant that Israel has had to dole out hundreds of millions of additional dollars for liquid fuel to run its electricity grid.

And last week witnessed a further, violent aftereffect of the “Arab Spring”—three Grad rockets (advanced Katyushas), launched from the Gaza Strip, landed 20-25 miles away in open fields outside the central Israeli cities of Ashdod and Rehovot. There were no casualties and air force jets hit what Israel called “terrorist” targets in the strip in retaliation (apparently also causing no casualties).

But the direction is clear. After the Israel-Hamas prisoner exchange, the region may be heading toward increased violence. If so, such violence would be part and parcel of the unfolding Islamisation of the region—both in terms of the anti-Zionist Islamist ethos and attendant concrete developments on the ground, one of which is the giant arms smuggling operations that have followed the downfall of Gaddafi. Thus, the “Arab Spring” has brought both Islamization and chaos (and the Islamization will only benefit from this transitional chaos). Ordinary smugglers have collaborated with Islamists to plunder Qaddafi’s armories, and the Middle East’s clandestine arms bazaars are awash with Grads and relatively sophisticated shoulder-held anti-aircraft missiles. Israeli intelligence says that many of these weapons have recently made their way into the Gaza Strip via the Sinai Peninsula. One anti-aircraft missile was fired at an Israeli helicopter in a recent skirmish on the Sinai-Israel border.

All these developments suggest an accelerating trend in the Middle East that is far different from what many Western idealists anticipated when they coined the term “Arab Spring.” It’s a trend that could severely alter Muslim-Western relations across the board.

Benny Morris is a professor of history in the Middle East Studies Department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. His most recent book is One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict (Yale University Press, 2009).

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Why Islamists Are Winning

When secular politics fail, Islamism is the last big idea standing.

By BRET STEPHENS

Wall Street Journal,NOVEMBER 2, 2011

“This is not an Islamic Revolution.”

So opined Olivier Roy, arguably Europe’s foremost authority on political Islam, in an essay published days after Hosni Mubarak was forced from power in February. “Look at those involved in the uprisings, and it is clear that we are dealing with a post-Islamist generation,” he wrote. “This is not to say that the demonstrators are secular; but they are operating in a secular political space, and they do not see in Islam an ideology capable of creating a better world.”

Mr. Roy wasn’t alone in the sangfroid department. “I am not in the least bit worried about the Muslim Brotherhoods in Jordan or Egypt hijacking the future,” confided New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, with the caveat that their secular opponents would need some time to organize. Added his colleague Nicholas Kristof in a dispatch from Cairo: “I agree that the Muslim Brotherhood would not be a good ruler of Egypt, but that point of view also seems to be shared by most Egyptians.”

What reassurance. Nine months on, the Islamist Nahda party has swept to victory in Tunisia, the one Arab state in which secularist values were said to be irreversibly fixed. Libya’s new interim leader, Mustafa Abdel-Jalil, came to office promising “the Islamic religion as the core of our new government”; as a first order of business, he promises to revoke the Gadhafi regime’s ban on polygamy since “the law is contrary to Shariah and must be stopped.” Later this month, Islamist candidates—some of them Muslim Brothers, others even more religiously extreme—will likely sweep Egypt’s parliamentary elections.

It doesn’t stop there. Hezbollah has effectively ruled Lebanon since it forced the collapse of a pro-Western government in January. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s Islamist prime minister, cruised to a third term in parliamentary elections in June. Hamas, winner in the last vote held by the Palestinian Authority in 2006, would almost certainly win again if Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas dared put his government to an electoral test.

Why have Islamists been the main beneficiaries of Muslim democracy? None of the usual explanations really suffices. Islamists are said to be the unintended beneficiaries of the repression they endured under autocratic secular regimes. True up to a point. But why then have their secular opponents in places like Egypt been steadily losing ground since the Mubarak regime fell by the wayside? Alternatively, we are told that secular values never had the chance to sink deep roots in Muslim-majority countries. Also true up to a point. But how then Tunisia or Turkey—to say nothing of the Palestinians, who until the early 1990s were often described as the most secularized Arab society?

Closer to the mark is Mideast scholar Bernard Lewis, who noted in an April interview with the Journal that “freedom” is fairly novel as a political concept in the Arab world. “In the Muslim tradition,” Mr. Lewis noted, “justice is the standard” of good government—and the very thing the ancien regimes in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya so flagrantly traduced. Little wonder, then, that Mr. Erdogan’s AK party stands for “Justice and Development,” the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood’s new party is “Freedom and Justice” and, further afield, the leading Islamist party in Indonesia calls itself “Prosperous Justice.”

Still, the Islamists’ claim to “justice” goes only so far to account for their electoral successes. There is also the comprehensive failure of the Muslim world’s secular movements to provide a better form of politics.

The national-socialist brew imported from Europe in the 1940s by Michel Aflaq became the Baathist tyrannies of present-day Syria and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. Pan-Arabism’s appeal faded well before the death of its principal champion, Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Socialism failed Algeria; Gadhafi’s “Third Universal Theory” failed Libya. French-style laïcité descended into kleptocracy in Tunisia and quasi-military control in Turkey. Periodic attempts at market liberalization yielded dividends in places like Bahrain and Dubai but were never joined by political liberalization and were often shot through with cronyism.

That sour history leaves Islamism as the last big idea standing—and standing at a moment when tens of millions of young Muslims find themselves undereducated, semi- or unemployed, and uniquely receptive to a world view with deep historic roots and heroic ambitions.

What does its future hold?

Optimists say it need not be a reprise of Iran; that it could look more like Turkey; that the term “moderate Islamist” isn’t an oxymoron, at least in a relative sense. Then again, Turkey’s domestic and foreign policies inspire little confidence that moderate Islamism will be anything other than moderately repressive and moderately radical. As for Iran, signs of its own long-awaited turn toward moderation are as fleeting as the Yeti’s footsteps in drifting snow.

The good news is that after 31 years most Iranians have grown sick of Islam always being the answer, and the collapse of the regime awaits only the next ripe opportunity. The bad news is that a similar time-frame may be in store for the rest of the Muslim world, until it too becomes disenchanted with Islamist promises. Get ready for a long winter.

Tags: Indonesia, Islamic Extremism