UPDATES

Egyptian President Morsi and the case of the mysterious letter

August 3, 2012 | Allon Lee

Did he or didn’t he?

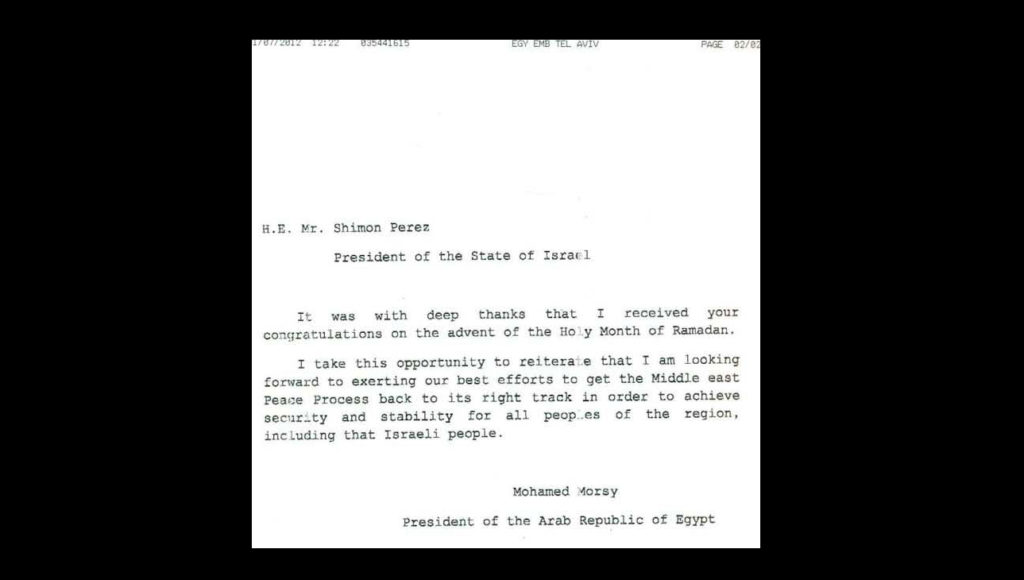

The saga continues over the authorship of a note purportedly sent by Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi to Shimon Peres, his Israeli counterpart, thanking him for his good wishes at the start of the Muslim festival of Ramadan.

Notwithstanding the poor syntax, misspelling “Peres” as “Perez” and lack of signature ( a good analysis of the sloppiness of the letter is here), the note is everything one would expect of a responsible and sober leader.

I am looking forward to exerting our best efforts to get the Middle east peace process back to its right track in order to achieve security and stability for all peoples of the region, including that Israeli people.

Except, of course, with the track record of virulently anti-Israel statements of intent by Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, this is no mere ceremonial exchange of niceties between two sovereign nations ostensibly at peace.

As soon as news of the letter became public in Israel, Morsi’s official spokesman Dr. Yasser Ali denied his boss had sent it. See here.

There is little dispute that the letter was faxed from the Egyptian embassy in Tel Aviv to Shimon Peres’ office.

Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East’s Tarek Radwan has a good summary of the chronology here, as well as some important background on the Brotherhood’s antipathy toward Israel and Jews. He suggests three scenarios concerning the letter’s provenance:

1. A rogue instigator “fabricated” the letter to create a diplomatic kerfuffle.

2. A member of the Egyptian diplomatic corps responded on President Morsi’s behalf.

3. Morsi ordered the letter written, or wrote it himself, but later denied sending it.

Radwan discounts the first as a conspiracy theorist’s delight, while the second possibility “highlights a level of miscommunication within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that at worst is disconcerting, but not catastrophic”.

The “last possibility is the most likely, and truly the most troubling” Radwan believes:

It goes without saying that a president is expected to maintain diplomatic relations with those countries where interests directly cross paths, regardless of personal feelings.

Much like the difference between campaigning and holding office, political realities will drive behavior that seems contrary to past positions.

The day Mohamed Morsi became President Morsi, he resigned from the Muslim Brotherhood in an effort to “represent all Egyptians” and convince the public that his actions remain independent of any previous affiliation.

If one assumes he did indeed write the letter, his spokesman’s adamant denial that he ever wrote a response to an ordinary diplomatic communiqué reflects a disturbing conflict within Morsi.

It portrays a man unsure of his position, whether as an objective statesman or an extension of the Muslim Brotherhood in the office of the executive.

Raphael Ahren in the Times of Israel echoes Radwan’s analysis, noting that Morsi has form in this area:

This, after all, is not the first time in his short presidency that Morsi has been quoted sounding friendly to a Middle Eastern power only to claim that he’s been misrepresented. In June, the Iranian Fars news agency reported that Morsi had promised to visit and strengthen relations with Tehran, and to “reconsider” the peace treaty with Israel. Fars claimed Morsi made these comments in an interview with one of its reporters in Cairo. But a spokesman for the then incoming Egyptian president insisted that Morsi had not given any interviews to the Iranians and that “everything that this agency has published is without foundation.”

Anyway, now comes the latest undenial.

The Egyptian newspaper al-Youm El Sabea has quoted an unnamed Egyptian official saying that “the letter was indeed sent to Israeli President Shimon Peres through diplomatic channels, and it was not appropriate for the Egyptian president to deny it…The letter was sent according to protocol in response to a letter that was received, which is what happens with all other letters. The presidential department of ceremonies responded to the letter and sent it to the Egyptian Embassy in Tel Aviv, which then sent it to Peres’ office.”

Meanwhile, Yitzhak Levanon, a former Israeli ambassador to Egypt, argues that Israel should have kept the letter a secret and not forced Morsi into denying it was sent:

With the publication of the letter, everybody in Egypt now forgets about their internal and domestic issues, and concentrates on this debate – did he or did he not send this letter to the Israelis? Morsi is embarrassed and we get nothing, no benefit, from this ping-pong…. Now that we’ve embarrassed him, he’ll think twice before answering any future letter.

But as Raphael Ahren noted: “why, then, would the Egyptian ambassador have purportedly given Peres the green light to publish it? Maybe, one insider speculated, it would have been undiplomatic for the Tel Aviv envoy to say no.”

Ultimately, this episode highlights the leadership tensions within the “new” Egypt but also confirms how official relations between Egypt and the Jewish state are now more vulnerable to emboldened Islamist forces.

– Allon Lee

Tags: Egypt