UPDATES

Egypt’s new Islamist constitution

December 5, 2012

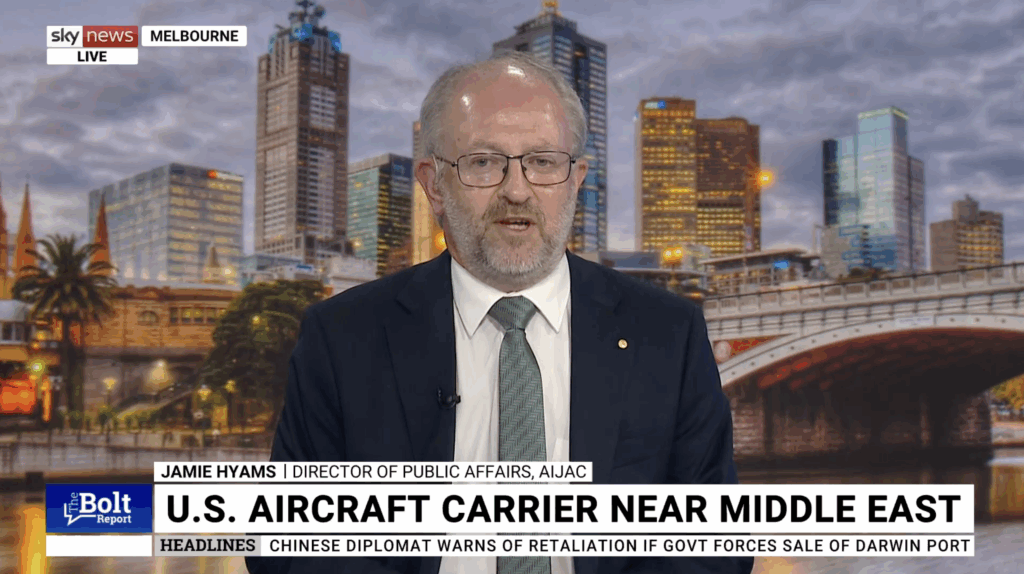

Update from AIJAC

December 5, 2012

Number 12/12 #01

On Friday, following an all night session, Egypt’s constitutional assembly rushed through a new constitution, which was promptly approved by Muslim Brotherhood President Mohammed Morsi, and will be put to a referendum on Dec. 15. The rushed constitutional process follows increasing political unrest there after Morsi published on Nov. 22 a decree giving himself near absolute powers, not subject to judicial review, to take measures he judges necessary ” to protect the country and the goals of the revolution.” But the unrest shows little sign of ending anytime soon.

First up is Washington Institute for Near East Policy Director Robert Satloff, together with Eric Trager, the Institute’s Egyptian politics expert, who argue that the constitution, which they expect to easily pass the referendum, is likely to seal a theocratic future for Egypt. While they note some ostensibly tolerant and democratic elements in it, they discuss how it is overall a non-pluralistic document produced by a non-pluralistic process, whereby non-Islamists were essentially absent from the drafting process. They note a numbers of ways in which the document privileges religious doctrine in all political debates, demands the state enforce religious principles and values, and limits minority rights, as well as giving the Egyptian military the autonomy they feel entitled to, and considerable independent power over defence-related issues. For this detailed look at what the new constitution portends from two top-notch scholars, CLICK HERE. Trager has also published two excellent pieces – here and here – both making the point that, given his history, it was always unlikely Morsi would act as a “moderate” democratiser.

Next up is American scholar Charity Wallace, who looks at one specific element of the constitution – its effect on Egypt’s women. Wallace notes that the constitutional assembly had only four women – all Islamists- and, not surprisingly, failed to include proposed clauses calling for women’s equality (except where contradicted by Sharia), or an element opposing human trafficking. But she is most concerned about an article requiring the state to “protect the authentic values of the Egyptian family”, and another a giving important political powers to the unelected conservative Islamic establishment at al-Azhar University. For her complete analysis and policy recommendations, CLICK HERE. Looking at another element of the new constitution – its provisions dealing with the military’s role – is American foreign policy pundit Walter Russell Mead.

Finally, American foreign affairs columnist Bret Stephens has a look at how President Morsi has manoeuvred very successfully to obtain the Muslim Brotherhood’s far-reaching goals. Moreover, the West has consistently underestimated both his ability and determination to achieve these goals, Stephens argues. He particularly stresses that while many insisted Morsi’s first challenge was to deal with Egypt’s economic problems, in fact, Morsi has shown that he sees his first challenge as consolidating political power for the Muslim Brotherhood, something he has repeatedly exploited opportunities to do. Stephens concludes that so far Morsi has shown himself to be master of the situation, operating with “potency and intelligence”, and it is time the West realised both this, and where, ideologically, he is using that mastery to take Egypt. For Stephens’ full argument, CLICK HERE. Also looking in more detail at the apparently systematic and determined consolidation of autocratic power by Morsi and the Brotherhood is Barry Rubin. Rubin also had a further analysis of the new Egyptian constitution here. Another analysis of Morsi’s path to consolidate power comes from Mideast scholar Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Two excellent reports on the realities of the liberal/Islamist clashes inside Egypt – from Raniah Salloum of Der Spiegel and Michael Petrou of Canada’s Maclean’s magazine.

- Some comment on recent Brotherhood moves by liberal Egyptian activists Ahmed Meligy and Ranya Khalifa.

- Other Arab critiques of the way Egypt is heading from

- and former Israeli Ambassador to Egypt Zvi Mazel.

- Syria’s regime cuts off the internet, amid fears of a major government offensive, reports the US is reconsidering its reluctance to intervene, and growing concern over possible use by the regime of their massive chemical weapon stocks in the near future.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

-

- Ahron Shapiro cuts through the myths and looks at the realities of Israel’s recent announcement to allow planning to advance for building in the E-1 area near Jerusalem. (More on the E1 controversy comes from the Jerusalem Post, from Jonathan Tobin and Rich Rickman of Commentary, and especially from Elliot Abrams, the American official who brokered American-Israeli understandings on settlements in 2004. Plus, Abrams gave a perceptive interview on this subject today on the ABC‘s “World Today”)

- Ahron Shapiro also had a good post on the worrying and unhelpful things that Palestinian official sources are saying about what they expect the recent UN vote will achieve for them.

- Sharyn Mittelman highlights some recent statements from US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton which explicate well the reasons for the current impasse in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations.

- Sharyn Mittelman also had a post on some of the incitement to genocide that came out of Hamas during the recent Gaza conflict.

- Or Avi-Guy discusses the latest in the Israeli election campaign, with former PM and current Defence Minister Ehud Barak bowing out of the contest, and former Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni throwing her hat in the ring with a new party.

- Daniel Meyerowitz-Katz had not one but two recent pieces on the Palestinian UN bid – one in the Australian Financial Review explaining why it is more likely to lead to lawfare than to peace negotiations and another on the ABC’s Religion and Ethics opinion site, pointing out the absurdity of siding with Sudan and other major human rights violators in abetting Palestinian efforts to take Israel to the International Criminal Court.

- AIJAC Executive Director Colin Rubenstein released a statement responding to Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr’s comments on Israeli announcements about settlements, which you can read here.

Egypt’s Theocratic Future: The Constitutional Crisis and U.S. Policy

Robert Satloff and Eric Trager

PolicyWatch 2001

December 3, 2012

Egypt’s hastily drafted constitution, which will likely pass an upcoming referendum, facilitates Islamist domination by co-opting the military.

Egypt’s newly drafted constitution, which will be put to a referendum on December 15, represents a tremendous step backward for the country’s democratic prospects. President Muhammad Morsi’s decision to rush the document through a constitution-writing assembly that non-Islamists abandoned, coupled with the many articles that Islamists in power can easily exploit, virtually ensures a theocratic Egyptian future. The charter also cements the Muslim Brotherhood’s deal with the military, granting the generals relative autonomy in exchange for accommodating the Brotherhood’s political ambitions.

BACKGROUND

Egypt’s Constituent Assembly has faced two key challenges since the Brotherhood-controlled parliament appointed it to draft the new constitution in June. First, its domination by Islamists upset its non-Islamist members, and by mid-November almost all of the latter had abandoned the assembly in protest. Second, following the Supreme Constitutional Court’s mid-June ruling that parliament had been elected unconstitutionally, the assembly became a target for litigation. After multiple postponements, a ruling on its legality was expected this week.

To preempt this ruling, however, Morsi issued a November 22 constitutional declaration that, in addition to asserting virtually unchecked power for himself, insulated the assembly from being dissolved by the court. When non-Islamists launched mass protests against the decree, Morsi responded by calling for completion of a draft constitution within twenty-four hours; the assembly in turn replaced many of the non-Islamists who had abandoned it with Islamists. On Saturday, Morsi approved the resulting draft and called for a national referendum on December 15. It is widely expected to pass: Islamists (who remain the country’s best-mobilized political forces) support it, and “yes” has won every plebiscite in contemporary Egyptian history.

The draft has some promising components. It maintains that “sovereignty is for the people alone,” not God; includes clauses on nondiscrimination and personal freedom; affords impressive privacy rights, including in electronic communications; and mandates a two-term presidential term limit. But it also offers a political system that is ripe for Islamist domination, and provides unprecedented constitutional protections for the military as part of an apparent deal to ensure its passage.

NONPLURALISTIC PROCESS YIELDS NONPLURALISTIC DOCUMENT

The draft constitution’s articles on the relationship between Islam and politics reflect the virtual absence of non-Islamists and religious minorities from the assembly that drafted it. While much depends on how future Egyptian governments interpret the constitution, a number of key passages provide Islamists with a substantial foothold for instituting their authority and advancing their agenda.

The draft’s approach to sharia (Islamic law) is one such example. Although it preserves the 1971 constitution’s second article, under which “Islam is the religion of the state” and “Principles of Islamic sharia are the principal source of legislation,” the new constitution is far stricter in specifying how legislators should examine sharia. Article 219 thus defines “principles of Islamic sharia” as including “general evidence, foundational rules, rules of jurisprudence, and credible sources accepted in Sunni doctrines and by the larger community,” thereby narrowing the range of interpretations on which legislators can draw by excluding Shiite doctrines, which were used for legislating under the 1971 constitution. And while the draft does not necessarily exclude the passage of laws that have no sharia basis, the combined effect of Articles 2 and 219 privileges religious doctrines in political debate, and therefore Islamists. Article 6 further bolsters this privilege by basing the political system on “the principles of democracy and shura,” the latter of which implies consultation restricted to qualified Islamic scholars.

The constitution also carves out a potentially large role for the state in enforcing religious doctrine. In this vein, Article 11 authorizes the state to “safeguard ethics, public morality, and public order, and foster a high level of education and of religious and patriotic values.” Meanwhile, Article 44 prohibits the “insult or abuse of all religious messengers and prophets,” thereby empowering the government to use religious justifications for curtailing free speech.

Finally, the constitution embraces a limited view of minority rights. While Article 3 permits Christians and Jews to be governed by their respective laws regarding personal status issues, the text is silent on the rights of other minorities such as Bahais and Shiites, who frequently suffer discrimination. According to Brotherhood leader Helmi al-Gazzar, this was intentional because “Bahais are a very eccentric group that is far from Islam,” while Shiites “worship Allah in a very strange way.” Article 43 similarly ignores these groups when it upholds the “freedom to practice religious rites and to establish places of worship for the divine religions,” which is typically interpreted as including only Sunnis, Christians, and Jews. Even these three groups are only guaranteed religious freedom “as regulated by law,” thereby enabling the continuation of discriminatory laws that complicate Christian attempts to build or renovate churches; such provisions are frequently used to justify sectarian violence.

THE BROTHERHOOD’S DEAL WITH THE MILITARY

The constitution does not privilege Islamist ideology and ambitions exclusively. It also satisfies two key military demands, thereby winning the generals’ cooperation in facilitating the draft’s passage. Indeed, the first articles that the assembly approved as it hurried to complete its draft on Thursday were those that pertained to the military.

First, the new constitution grants the military relative autonomy over its own affairs. Article 195 holds that the defense minister must be a member of the armed forces “appointed from among its officers,” thereby sparing the military from civilian oversight. Article 197 similarly establishes a National Defense Council to oversee the military’s budgets; at least eight of the council’s fifteen seats must be held by high-ranking military officials, avoiding the parliamentary oversight that the generals feared. Meanwhile, Article 198 maintains the military judiciary as “an independent judiciary” and allows civilians to be tried before military courts for “crimes that harm the armed forces.”

Second, the constitution grants the military substantial influence — and perhaps even veto power — over the conduct of war. Article 146 states that the president cannot “declare war, or send the armed forces outside state territory, except after consultation with the National Defense Council and the approval of the House of Representatives with a majority of its members.” The text also seemingly equalizes the defense minister and the president during wartime: Article 146 calls the president the “supreme commander of the armed forces,” while Article 195 declares the defense minister the “commander-in-chief of the armed forces.”

Although the Brotherhood previously rejected such concessions, the new draft charter represents the group’s realization that it needs the military to advance its agenda in the current environment. Given that Egyptian judges are protesting Morsi’s actions, with many refusing to monitor the December 15 referendum, the Brotherhood must rely on the military authorities to open polling places and administer the vote, as they have done successfully five times since last year’s revolution.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

So far, the Obama administration has effectively sided with Morsi against his non-Islamist opponents. Since the current crisis erupted two days after the Gaza ceasefire, which itself ended with effusive American praise for Egypt, the State Department has issued two key statements — the first after Morsi’s power-grabbing decree, the second after the hasty approval of the draft constitution and announcement of a referendum. Both statements muted any criticism and essentially echoed Morsi’s statement that opponents should express their view in a “no” vote.

Now, with Egypt’s judiciary divided over whether to supervise the referendum and other groups, such as the mosque preachers syndicate, offering to do the job, Washington faces another test of whether its honeymoon with Morsi trumps its support for universal principles of constitutionalism. The Obama administration’s position will have powerful implications for the content of U.S.-Egyptian relations and the direction of constitutional development in other Arab transitional democracies.

Robert Satloff is executive director of The Washington Institute. Eric Trager is the Institute’s Next Generation fellow.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Egypt’s misogynistic democracy

In the draft constitution, women are second-class

By Charity Wallace

NEW YORK DAILY NEWS

Sunday, December 2, 2012, 4:21 AM

Friday, Egypt’s constitutional assembly approved a new draft constitution after a marathon all-night session. President Mohammed Morsi has promised that the constitution will be put up for a referendum “soon” — likely within the next two weeks.

The proposed founding document does not represent all Egyptians. Islamists seized control of the drafting process, shutting liberals, secular Egyptians and Christians out of the debate.

What is perhaps most significant and disappointing is the fact that this has done serious damage to the interests of Egyptian women — and, by extension, women throughout the Arab world.

The 85-member assembly — down from 100, thanks to the resignations of those who opposed Islamist domination of the council — contained just four women, all of whom were Islamists themselves.

It’s no surprise, then, that the proposed constitution fails to enshrine equal rights for women.

For instance, the constitutional assembly rejected a proposed article banning human trafficking and the sale of women and children. Opponents complained that it would have prohibited the marrying of girls under 18, which is permitted under Shari’a law.

A clause that would have guaranteed women’s equality, even with an exception if equality violated Islamic law, did not make it into the final draft of the constitution. The draft simply states that “citizens are equal before the law and equal in rights and obligations without discrimination” — remaining silent on the question of whether women will have any explicit protection.

Another clause mandates that al-Azhar — Egypt’s official religious arbiter — be consulted on matters related to Shari’a. Al-Azhar is an unelected body, and once vested with this power, it could act on the radical rhetoric it has embraced in the past.

Yet another clause compels the state to “protect the authentic values of the Egyptian family.” Many observers are worried that this could give protection to practices like female genital mutilation.

If there was any remaining doubt that women would be viewed as second-class citizens in the new Egypt, the constitution calls on the state to “balance between a woman’s obligations to family and public work.”

Many Egyptian women are appalled by these developments and are demanding the same rights and privileges afforded their fathers, husbands and sons. But the Islamist-dominated constituent assembly — not to mention Morsi and his male-dominated cabinet — have not appeared interested in listening.

The United States recognizes the importance of protecting women’s rights around the world. Influential and powerful women, such as Laura Bush and Secretary of State Clinton, are vocal and ardent advocates for women.

So how can America ensure that women are not oppressed in the new Egypt?

The first step is to respect Egypt’s autonomy and the democratic process there. Egypt is a sovereign nation with a unique religious and cultural identity that is largely compatible with liberal democracy.

No one wants the United States to dictate a new constitution to the Egyptian people. Nor is anyone suggesting that there aren’t legitimate cultural differences between a liberal Western democracy and a budding Middle Eastern democracy. Many of these come to bear on questions of gender equality.

However, America does have a moral responsibility to stand up for universal principles of human freedom, principles that are shared by millions of Egyptians.

Since the United States gives Egypt about $2 billion in aid every year, it is clearly within our rights to urge the new government to guarantee certain core protections for women.

And there are specific policies we can ask for, such as raising the approval threshold for constitutional amendments to 75% of the assembly and expanding the official public debate period scheduled for after the draft passes.

No, getting the right language in the constitution won’t simply transform Egypt overnight.

But what’s written there can serve as an invaluable legal and rhetorical tool for proponents of a free and fair Egypt in the future.

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice explained the importance of the exact words in a constitution in a recent address at Southern Methodist University.

She said: “If you don’t think constitutions matter, just remember this: When Martin Luther King Jr. wanted to say that segregation was wrong in my hometown of Birmingham, he didn’t have to say that the United States had to be something else — only that the United States had to be what it said it was.”

Her words demonstrate why America needs to fight for women’s rights in the founding document of the new Egypt.

Wallace is the director of the Women’s Initiative at the Bush Institute.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Morsi as Master

You have to admire Mohammed Morsi’s sense of timing. Or, rather, his confident indifference to it.

Early last week, the Egyptian president and Muslim Brother brokered a cease-fire between Israel and Hamas with the assistance of the Obama administration. On Wednesday, a story in the New York Times gave the blow-by-blow account of the negotiations from Mr. Obama’s angle.

“Mr. Obama told aides he was impressed with the Egyptian leader’s pragmatic confidence,” the Times reported. “He sensed an engineer’s precision with surprisingly little ideology. Most important, Mr. Obama told aides that he considered Mr. Morsi a straight shooter who delivered on what he promised and did not promise what he could not deliver.”

Going on in this gushing vein, the Times concluded: “As for Mr. Obama, his aides said they were willing to live with some of Mr. Morsi’s more populist talk as long as he proves constructive on substance. ‘The way we’ve been able to work with Morsi,’ said one official, ‘indicates we could be a partner on a broader set of issues going forward.’ “

A day after this era of good feelings had begun, Mr. Morsi awarded himself dictatorial powers. The worst that White House spokesman Jay Carney would say is that the administration is “concerned.”

Mr. Morsi’s decision ostensibly comes in response to his dissatisfaction with Egyptian judges, many of them holdovers from Hosni Mubarak’s regime, who have handed down too many acquittals or soft sentences in trials of ex-regime figures. Worse, those same judges may dissolve the Islamist-dominated assembly that is drafting a new constitution, much as they dissolved the Islamist-dominated parliament in June, shortly before Mr. Morsi’s election.

Mr. Morsi’s solution was to issue a decree giving him the right to supersede any judicial rulings of which he disapproves. He promises to revoke the decree once a new constitution is approved and Egypt’s political transition is complete. Egyptians are supposed to take it on trust, as is the rest of the world. It’s a bad bet.

From the start of Egypt’s revolution in January 2011, observers have consistently underestimated the strength and ambition of the Muslim Brotherhood.

First, the story was that the Brotherhood had been late to the party in Tahrir Square and therefore wouldn’t reap the political spoils. In fact, it reaped nearly all of the spoils.

Next, that the Brotherhood would be faithful to its declared promise not to contest the presidential election. It broke the promise without paying a penny of a political price.

Later, that even after its victories at the polls the Brotherhood would respect and remain subservient to the country’s true (and secular) masters in the military. Mr. Morsi sacked Egypt’s top military leaders within two months of coming to office, replacing them with men who owed their loyalty to him.

Then, that the Brotherhood would defend the usual rules of diplomacy, such as protecting foreign embassies. It took a furious phone call from Mr. Obama to move Mr. Morsi to protect the U.S. Embassy from a mob that came close to sacking it.

Finally, that the country’s dependence on foreign aid and tourism will curb the government’s appetite for naked power grabs. But Mr. Morsi’s power grab came just two days after Egypt had initialed, though not finalized, a $4.8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. Mr. Morsi already won $1 billion in debt forgiveness from Washington intended to bolster Egypt’s “transition to democracy.”

It is true that Mr. Morsi adopted a less strident position toward Israel during this month’s brawl in Gaza than some expected. There were also reports Monday afternoon that Mr. Morsi had somewhat amended his judicial decree, though not when it comes to the constitutional assembly. If true, it is evidence of Mr. Morsi’s canniness and tactical flexibility. Moderation is another matter.

Even now, Western analysts continue to misread Mr. Morsi, imagining that his primary political challenge is to improve the Egyptian standard of living. Not so. His real challenge is to consolidate the power of the Brotherhood.

So far, he’s passed every test. His domestic opponents know they cannot match the Brotherhood’s strength in the streets. The army lacks the appetite, and probably the means, for an Algerian-style coup and bloody civil war. The West, including Israel, is trying to make the best of things and will go further to accommodate Egypt’s new pharaoh than he will go to accommodate them. Everywhere Mr. Morsi looks, he is the master.

It may take some time for the West fully to appreciate the ugliness of Egypt’s new regime. For now, it is enough to appreciate its potency and intelligence. Mr. Obama was right to praise Mr. Morsi’s “engineer’s precision.” He would be a fool to imagine that such precision can be divorced from an ideology for which Mr. Morsi once went to prison, and which now rests in his hands to impose.

Tags: Egypt