UPDATES

Egypt’s First Round Election Results

June 1, 2012

Update from AIJAC

June 1, 2012

Number 06/12 #01

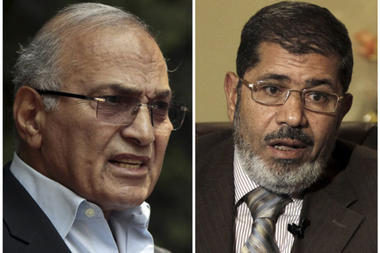

This Update focuses on analysis of the outcome of the Egyptian Presidential elections last week, where contrary to most expectations, the candidates to make it into the second round were Muslim Brotherhood representative Mohamed Morsi and former air force head Ahmed Shafiq, who is seen as closely associated with the Egyptian military and the former Mubarak regime.

First up is the reliably well-informed expert on Egyptian politics from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Eric Trager, looking at the success of the Muslim Brotherhood. He notes that analyses and polls which had predicted a poor showing for Morsi failed to account for the fact that not only is the Brotherhood the best organised political force in the country, it is in essence the only organised political force. He then goes on to explain how the Brotherhood is able to create such a disciplined and committed organisation, which appears to have made all the difference in this election. For all of Trager’s analysis, CLICK HERE. Plus, American expert Stephen Cook has a good look at why he and so many other analysts looking at Egypt got this result so wrong and why polls of Egyptians were so unreliable.

Next is Barry Rubin looking at the implications of the poll for various Egyptian forces. Rubin argues that, contrary to many commentators, this election was actually a setback for Islamist forces in that they failed to get a majority, in stark contrast to last year’s parliamentary election. He note that the liberals and democrats have been cut off completely from this poll, and prophetically warned that there is a danger of a violent reaction, especially from the Salafist extremists (and subsequently Shafiq’s campaign headquarters was burned down). For Rubin’s look at the performance of the various parties and factions, CLICK HERE. More detail on the breakdown of the voting by district, party and demographics is here.

Finally, this Update offers some views on the election’s implications for Israel from a Jerusalem Post editorial. The Post argues that while Shafiq is the candidate most likely to maintain the peace treaty with Israel, he also the candidate of Egypt’s authoritarian traditions, but notes that Mursi’s extremism, and even tolerance of antisemitism at his rallies, is clearly worrying. The paper goes on to note that given the extreme anti-Israel views of third place finisher, communist-Nasserist Hamdeen Sabbahi, and the views expressed by Egyptians in polls, things look dark for Israel-Egypt relations even if Shafiq wins. For the Post’s argument in full, CLICK HERE. Israeli journalist Oren Kessler has more on Israel concerns about the election result at Foreign Policy.

Readers may also be interested in:

- Analyst Zack Gold argues the Morsi versus Shafiq outcome in Egypt was the worst of all possible worlds. Some similar sentiments come from liberal Egyptian writer

- Columnist Mark Steyn takes on the naive assumption of so many that Facebook and Twitter use would lead to democracy in Egypt.

- Israeli commentator Uri Heitner argues that Shafiq must be the hope for the second round in Egypt for anyone enlightened. Interestingly, American academic and former official Elliot Abrams argues Egypt may actually be better off in the long run with a Morsi victory, allowing the Islamist model to be tried and fail.

- Canadian academic Salim Mansur argues the military is the only hope for transitioning to genuine democracy in Egypt.

- George Friedman of Stratfor applies some lessons from the widespread misreading of Egypt’s likely trajectory to other aspects of the Arab Spring, including especially Syria.

- AIR correspondent Amotz Asa-El has a detailed look at the troubled situation in Sinai, and what Egypt’s next president may do about it.

- Veteran Australian Jewish leader Isi Leibler takes issue with a Jerusalem Post editorial and has some advice for Israel’s new opposition leader, Shelly Yachimovitch of Labor.

- In Pakistan, six people are sentenced to death for dancing and singing at a wedding. In Saudi Arabia, outrage over a toy from McDonald’s “Happy Meal” alleged to insult the prophet Muhammad.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- A post about how the Iranians appear to be doubling down and accelerating their nuclear efforts in the wake of the Baghdad nuclear negotiations last week.

- A post evaluating Australia’s response to the violence in Syria, especially the massacre at Haoula.

- A post on the latest UN outrage – appointing as a “Leader for Tourism” a man banned from travel for his alleged misdeeds – Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe.

- A post about how the plight of West Bank Christians goes unreported when they are threatened by Muslim neighbours.

Reports of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Demise Were Greatly Exaggerated

Eric Trager

The New Republic,

May 28, 2012

In the run-up to the first round of Egypt’s presidential elections, which concluded on Thursday, the Muslim Brotherhood’s downfall was widely anticipated. Only four months after winning a 47-percent plurality in the parliamentary elections, The Washington Post reported that the Brotherhood’s stock was “plunging,” while The Wall Street Journal insisted that the Brotherhood’s fortunes had “faded” due to “mounting public criticism” and “internal defections.” Pre-elections polls bolstered this storyline, pegging support for notoriously uncharismatic Brotherhood nominee Mohamed Morsi at a paltry three to nine percent, and it was widely expected that many Muslim Brothers would buck their parent organization and support ex-Brotherhood leader Abdel Monem Abouel Fotouh.

Yet reports of the Muslim Brotherhood’s demise, it seems, were greatly exaggerated: Morsi won a first-round plurality with roughly 26 percent of the vote, and will face former Mubarak regime figure Ahmed Shafik in the second round, which begins on June 16. Morsi’s strong performance, which comes despite his many deficiencies as a candidate, is a testament to the Muslim Brotherhood’s unmatched mobilizing capabilities, which have made the organization’s political dominance practically inevitable since the moment that Hosni Mubarak resigned.

It is not merely that the Muslim Brotherhood is Egypt’s “best organized” group, as many commentators frequently note. It is the only organized group, with a nationwide hierarchy that can quickly transmit commands from its Cairo-based Guidance Office (maktab al-irshad) to its 600,000 members scattered throughout Egypt. The hierarchy works as follows: The twenty-member Guidance Office sends its marching orders to deputies in each governorate (muhafaza), who communicate with their deputies in each “sector” (quita), who communicate with their deputies in each “area” (muhafaza), who communicate with their deputies in each “populace” (shoaba), who finally communicate with the leaders of each Brotherhood “family” (usra), which is comprised of five Muslim Brothers and represents the organization’s most basic unit. This chain of command is used for executing all Guidance Office decisions, including commanding Muslim Brothers to participate in protests, organize social services, and—during the most recent elections—campaign and vote for Mohamed Morsi.

There are two additional elements of the Muslim Brotherhood’s internal structure that ensure that the Brotherhood leadership’s commands are followed. First, the social lives of members are deeply embedded within the organization. Muslim Brothers meet with their five-person Brotherhood “families” at least weekly, where they study religious texts, discuss politics, organize local Brotherhood activities, and share their private lives with one another. Muslim Brothers’ deepest personal relationships thus emerge within the organization, and there is a great disincentive to buck the Brotherhood leadership’s commands, since doing so risks alienation from their closest friends and mentors.

Second, the very process of becoming a Muslim Brother ensures that only those who are deeply committed to the organization and its principles become full-fledged members. Indeed, becoming a Muslim Brother is an intricate five-to-eight-year process, during which each member is gradually promoted through four tiers of memberships before finally becoming a “working Brother” (ach amal). (In order to attain the third level, a rising Muslim Brother’s supervisors must affirm that he has studied the works of Brotherhood founder Hassan al-Banna; memorized specific chapters of the Qur’an; and shown himself to be “a good follower of the Muslim Brotherhood organization’s decisions,” as one young Muslim Brother engaged in this process told me last March.) Those who become Muslim Brothers are highly unlikely to turn their backs on an organization in which they have invested so much time and energy in joining.

Morsi’s victory in the first round of the presidential elections demonstrates the importance of these structures in determining Egypt’s political future. While other constituencies—including Egyptian Christians and Salafists—are significantly larger than the Brotherhood, none can mobilize similarly committed supporters as consistently or cohesively. In this vein, while some of the major Salafist organizations endorsed ex-Brotherhood candidate Abouel Fotouh for president, many prominent Salafists backed Morsi—including leaders from Salafist organizations that had officially supported Abouel Fotouh. By contrast, the Brotherhood could count on its membership to vote en masse for Morsi—even despite pre-elections reports that many Brothers might support Abouel Fotouh.

The Brotherhood’s unmatched mobilizing capabilities suggest that, in a certain sense, it hardly matters whom they nominate for office. The gruff, uncharismatic Morsi was, after all, the Brotherhood’s “spare tire”—a reluctant understudy forced to perform after the group’s initial nominee, Khairat al-Shater, was disqualified from the elections due to a technicality. Moreover, Morsi made little attempt at reaching out to the non-Islamist public, whereas the eloquent Abouel Fotouh drew support from a broad coalition that included Salafists on the far right and socialists on the far left. But in a presidential contest featuring five major candidates, Abouel Fotouh’s broad coalition was no match for the Brotherhood’s reliable legions of foot-soldiers, who could mobilize superior get-out-the-vote efforts in every Egyptian governorate.

The Brotherhood’s disciplined infrastructure has thus put Mohamed Morsi one election away from Egypt’s presidency, and—barring massive fraud—he stands an excellent chance against former prime minister Shafik. While Shafik can count on support from Egyptian Christians and many of the rural clans that previously backed Mubarak’s ruling party, Morsi is already drawing support from many non-Islamists who fear a return to the old regime more than a Brotherhood-dominated Egypt. Moreover, early reports indicate that, faced with the choice between the autocratic Shafik and theocratic Morsi, many voters will stay home—a decision that will bolster Morsi, since low turnouts benefit well organized parties.

Of course, the importance of strong organizations in securing political victories is hardly unique to Egypt. But when only one group can organize effectively in a newly competitive political environment, single-party domination becomes practically inevitable—with potentially devastating consequences. After all, the dominant party can nominate just about anyone, and win. And if it uses its power to prevent potential competitors from emerging, it can also get away with just about anything.

Eric Trager is the Next Generation Fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Egypt’s Presidential Election is a Defeat (Perhaps Only Temporary) For the Islamists

by Barry Rubin

Pajamas Media

May 27, 2012

Muhammad Mursi (Muslim Brotherhood), 25.3 percent

Ahmad Shafiq (ex-general, ex-prime minister), 24.9 percent

Hamdin Sabbahi (radical left), 21.5 percent

Abdul Moneim Aboul Fotouh (“moderate Islamist), 19 percent

Amr Moussa (radical nationalist), less than 10 percent

While the Brotherhood claims victory, the election was actually a defeat—at least temporary and possibly less important than it seems—for the Brotherhood and Islamism. Here’s why.

The Islamist Camp

Note that only about 44 percent of voters backed an Islamist candidate, compared to 75 percent in the parliamentary election, while only about 25 percent voted for the Muslim Brotherhood compared to about 47 percent in the parliamentary vote. Why?

To begin with, the two top Islamist candidates were removed by the election commission, the Brotherhood’s first choice and the only Salafist candidate. Presumably, many voters stayed home or opted for their second choice party. The question is whether those who crossed the line and voted for a non-Islamist will return to the Brotherhood in the second round.

A key question is the 25 percent who backed a Salafist in the parliamentary election but could not do so in this one. Did they stay home, or vote for the Brotherhood or the “moderate Islamist,” or for a secular party? And again, will most of them back the Brotherhood or a Mubarak era politician?

Clearly, the mistakes made by the Islamists were costly, and they do make many errors. The Salafists nominated a candidate who was vulnerable to vetting. He didn’t meet the qualifications of purely Egyptian citizenship for himself and his family.

On the Brotherhood’s part, victory in the previous elections made them more radical and more arrogant. They mistakenly cast off the cloak of pretended moderation too soon and too completely. So much for the “Turkish model!” This hubris scared some voters. Shafiq’s campaign managers warned voters that to elect Mursi would set off a battle for an “Islamic empire.”

But note this theme of radicalism going along with victory because it is going to be one of the most important of all. Let’s summarize it:

When Islamists win, they become bolder and more aggressive. Western observers who talk about moderating Islamism think the opposite.

An opposing camp, however, those who argue all Muslims “must” be Islamists and that political Islam inevitably sweeps all before it have also been proven wrong. As I try to explain, this is a political struggle that can go either way depending on circumstances.

Islamism is by no means immune to social conditions. The strongest support for Mursi is in Egypt’s poor, underdeveloped south; the weakest backing is in the cities.

Yet let’s also remember that the Islamists are still heading for control over Egypt. The parliament, which they run, is going to make the rules and write the constitution. If they don’t like who becomes president, they will reduce his powers.

Some argue that voters left the Islamists because they had thought they would be “different” and “honest” but have concluded that they are just regular politicians. It’s hard for me to understand how this can be true, however, because they haven’t actually done anything yet! Not a single law has been passed; no constitution has been written.

A more likely explanation, I think, is that either the Brotherhood scared them by being so extreme or they want to balance its power by having some institutions in the control of others.

A final note, the phenomenon of “moderate Islamism” is not a significant player here. It was a “one-man” operation (and I don’t believe Aboul Fotouh was more than marginally more moderate) and has no political party or representation in parliament. While the 18 percent of the vote it received seems significant, many of those voters were possibly more radical than the Brotherhood itself because of the Salafist endorsement.

The Non-Islamist Camp(s)

Note well that the three non-Islamist candidates had a majority. This means that if voters stay within these two camps, Shafiq will be elected president.

The main irony is that their leading candidate shows support for the kind of rule being delivered by the army junta now and even by the (supposedly) despised Mubarak regime. A lot of Egyptians want quiet and order. And Shafiq outpaced the alternative “establishment” candidate Amr Moussa because he is even more bland and moderate.

Again, though, note that Shafiq could be a president with few powers facing a parliament that is handcrafting a constitution intended to bring Islamism. Moreover he has no political organization.

Or does he? Perhaps he has one that can be called the Egyptian army. A key point: If the Brotherhood doesn’t make the army very happy (financially), there might be some serious confrontations. In the longer run, there could even be a coup and that would return Egypt back to where it was politically before the whole “Arab Spring” business began!

The biggest shock of the election was the massive vote for the communist-Nasserist Sabbahi of the al-Karamah party. Does this show that there is a floating “radical vote” that cares less about ideology than about massive change? His voters mainly came from big cities.

Sabbahi is as dangerous as any Salafist—as anti-American and as eager to go to war against Israel—though he lacks a strong organization. Is this support for him, though, merely a more militant expression of nostalgia for the old regime likely to benefit the anti-Brotherhood side or a yearning for upheaval that might make people almost equally willing to vote for a Nasserist or an Islamist? We will find out.

Is Islamism continuing to march forward? Yes. Remember this principle: The Key to “Coopting” Islamists is for them to lose and accept defeat. But what if they win victory, especially an overwhelming victory in practice, they become more aggressive.

The Brotherhood’s recent history (and also that of Hamas, Hizballah, and the Turkish regime) proves this point and that’s why Western policies of encouraging the Islamists as a way to moderate them are wrong.

At this point, the issue depends on how smart the Islamist leaders are going to be. In retrospect, they made a mistake in running a candidate for president. If they had thrown their backing behind a non-Islamist figurehead and then made him a ceremonial president, the Brotherhood would be more respected and better off today. Ultimately, it cannot control its naked lust for power. The presidential election will make it more eager to transform Egypt’s laws.

In addition, keep in mind the importance of violence. The Salafists are hopping mad, believing they’ve been cheated. It is likely they will attack secularists, women who evince “non-Muslim” behavior, and Christians. In some areas, they will raid police stations. The question is whether such violence will build a revolutionary base or drive frightened Egyptians into the arms of Shafiq and the army.

Finally, the liberals are cut out entirely, partly due to the conditions of Egypt, partly to their own ineptness. Ahmed Khairy, spokesman for the Free Egyptians Party, a secular grouping that’s closest to what Western democracy enthusiasts would like to see in Egypt, described the election as “the worst possible scenario.” He called Mursi an “Islamic fascist” and Shafiq a “military fascist.”

If that’s how a moderate sees the choices, though it’s not fair to Shafiq, it shows how bad things are in Egypt.

Back to Top

————————————————————————

Whither Egypt?

Were preliminary results in Egypt’s first round of presidential elections good for the Jewish state or bad for the Jewish state?

On the positive side, there was a sharp fall in support for the Islamists. If in the parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafist Nour party garnered between them 75 percent of the vote, in the presidential elections the two Islamist candidates – Mohammed Mursi and Abdel Moneim Abul-Fotouh – managed to receive just 44% of the votes. This seems to indicate a public backlash against calls on the part of the Islamists to implement Islamic law.

Also, the man who garnered the second largest number of votes was Ahmed Shafiq. An Egyptian Air Force commander, a long-time aviation minister and the last prime minister under the Mubarak regime, Shafiq enjoys strong support from the Coptic Church and the liberal-minded upper-class who stand to lose most from increasing emphasis on Islamic piousness in the public realm. Shafiq has voiced his willingness to visit Israel provided the Jewish state “gives something to show it has good intentions.”

He would undoubtedly maintain the peace treaty with his country and Israel.

Unfortunately, Shafiq, whose popularity is less a product of his personal attraction and more to do with the fear of the meteoric rise of extremist political Islam and concern over lawlessness, is also a defender of some of the less democratic aspects of Egyptian rule. He has close ties to big business and high-ranking military personnel and seems to endorse continuing Egypt’s much hated, 30-yearold “emergency law” allowing extrajudicial detention. In cases of emergency, his platform suggests, the application of such measures should still be exempt from parliamentary review.

Still, Shafiq is undoubtedly the best candidate from an Israeli perspective. However, it was Mursi, the Muslim Brotherhood’s candidate, who appears to have received a slim plurality of the votes. Mursi, who has a PhD in engineering from the University of Southern California, has a track record of inflammatory statements about Israel, including repeatedly calling its citizens “killers and vampires.”

Last month, Mursi sat impassively at a Cairo stadium rally on his behalf as a radical preacher pledged to create a new Islamic caliphate based in Jerusalem, and an emcee led the crowd in chants of “Banish the sleep from the eyes of the Jews; come on, you lovers of martyrdom, you are all Hamas!” The candidate has called for the 1979 peace treaty with Israel to undergo “revisions.”

Mursi is also a proponent of basing Egyptian law on Shari’a, the religious code of Islam. He led a boycott of a major Egyptian cellphone company because its founder, Naguib Sawiris, a Coptic Christian, had circulated on Twitter a cartoon of Mickey Mouse in a long beard with Minnie in a full-face veil – a joke Mursi said insulted Islam.

In essence, in the final stage of presidential elections, slated for June, we will be witnessing a rematch of the struggle that has driven Egyptian politics for six decades, between secular authoritarians – represented by Shafiq – who vow to restore stability, and Islamists – led by Mursi – who promise a novel experiment in religious democracy.

Shafiq still has a real chance of beating the Islamist Mursi: The three non-Islamist candidates enjoyed a majority of the vote. If these votes go to Shafiq he would win. To succeed, Shafiq will have to woo most of the 20% of Egyptian voters who supported the communist-Nasserist Hamdeen Sabbahi, no easy task.

In an interview with the Iranian Fars news agency, Sabbahi said he would “tear up” the peace treaty with Israel and would not recognize a “Zionist element” that occupies Arab land. He also called to form an Egyptian-Turkish- Iranian alliance, noting relations with Iran had deteriorated “for no clear reason.”

In short, Sabbahi’s supporters might be more inclined to support the Muslim Brotherhood than the pragmatic Shafiq.

And even if he succeeds beating Mursi, Shafiq will preside over a parliament controlled by the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists that can effectively marginalize him. He will also have to cater to an Egyptian society that is virulently anti-Israel.

A recent BBC poll found 85% of Egyptians hold negative views of Israel, up 7% from the year before. Under the circumstances, it is difficult to be overly optimistic about the future of Israeli-Egyptian relations.

Tags: Egypt