UPDATES

Charting a Biden Administration foreign policy

January 22, 2021 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

01/21 #03

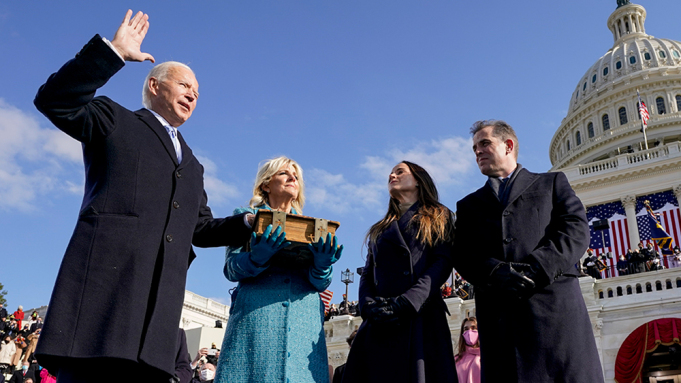

With US President Joe Biden now having been duly sworn in, this Update offers some additional knowledgeable analysis of what his Administration’s foreign policy directions and priorities are likely to be, as well as suggestions about what they should be. Obviously, the Middle East is the primary, but not exclusive, focus.

We lead with noted Israeli columnist and commentator Haviv Rettig Gur, who argues that while the Biden Administration may be inclined to pivot away from the policies of the Trump Administration in the Middle East, it will likely find it all but impossible to do so. He notes that the logic of the Obama Administration’s outreach to Iran – the argument that this would moderate the regime’s behaviour – has now been proven wrong, while the Obama Administration’s failed hopes for Israeli-Palestinian peace also received a dramatic reality check. Furthermore, Rettig Gur argues, the rise of China will be the Administration’s top priority and force a significant redevelopment of diplomatic and strategic resources. He has many more insightful things to say, and to read them all, CLICK HERE. More on China’s growing role in the Middle East and the challenges this creates for the US comes from noted international affairs analyst Robert Kaplan.

Next up is Washington Institute strategic expert Michael Eisenstadt reviewing Biden Administration security policy challenges and likely direction in the Middle East. He argues the Administration will need to recognise that the region’s serious problems cannot be solved, only managed, and the US military in the region will need to work on the nimble use of force on a limited scale to help do so. He says that building on the Abraham Accords between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, and other regional countries may be the key to creating the partnerships that can genuinely address the region’s structural problems. For Eisenstadt’s full discussion, CLICK HERE.

Finally, veteran US official specialising in the Middle East Dennis Ross counsels the Administration to be patient on the Iran nuclear portfolio. Ross, who served as President Obama’s advisor on Iran for two years, notes Iranian attempts to create a sense of urgency that will lead to the removal of US sanctions, but points out that the Biden team has clearly signalled Iran will need to return to compliance with the 2015 JCPOA nuclear deal first, which will take some time. He proposes that the Biden Administration pursue a “less for less” arrangement that will see Iran end its worst nuclear violations in exchange for very limited sanctions concessions that do not limit US future leverage to eliminate the problems of the JCPOA and also deal with Iran’s other rogue behaviours. For his complete argument, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- Additional good arguments that the JCPOA nuclear agreement is not the way forward with Iran, one jointly from historian and former Israeli diplomat Michael Oren and Israeli intellectual Yossi Klein Halevi, and another from journalist turned thinktank head Cliff May.

- Some recommendations on dealing with the Hezbollah threat for the new Administration, from expert Emanuele Ottolenghi.

- Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu’s message of congratulations to US President Joe Biden & VP Kamala Harris.

- An argument that confronting antisemitism is the key to eventually making Israeli-Palestinian peace.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- AIJAC’s Naomi Levin interviews Jonathan Schanzer, vice president of research at the Washington DC-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies, about the foreign policy implications of Joe Biden’s inauguration address.

- AIJAC’s Ahron Shapiro offers some predictions on what to expect from the Biden Administration in the Australian Jewish News.

- AIJAC’s Jamie Hyams discusses the Biden Administration’s challenges on Iran, in the Canberra Times.

- AIJAC’s Sharyn Mittelman in the Herald Sun on the importance of Holocaust education in countering right-wing extremism.

Joe Biden wants to erase the last four years. In the Mideast, that won’t be easy

A dramatic new political reality has dawned in Washington. But back in the Middle East, a distracted US president won’t have much room to maneuver on Iran and the Palestinians

By HAVIV RETTIG GUR

Times of Israel, 21 January 2021

US President Joe Biden speaks after being sworn in as the 46th President of the US during the 59th Presidential Inauguration at the US Capitol in Washington, January 20, 2021. (Patrick Semansky/Pool/AFP)

There’s a new president in the White House who has already shown himself to be a radical departure from the last one. In his first hours in office, Joe Biden signed executive orders freezing or reversing some of his predecessor Donald Trump’s signature policies: the Mexico border wall, the ban on travel from several Muslim nations, the American withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, and so on.

In the Middle East, Israelis, Saudis, Iranians, Palestinians, and many others are bracing for a similar dramatic pivot in America’s policies toward the region. The painful sanctions imposed by Trump on Iran, Trump’s freeze of aid to the Palestinians and recognition of Israel’s West Bank settlements, the backing for Israeli-Arab normalization agreements and the boosting of the Israeli-Saudi alliance to contain Iranian ambitions throughout the Arab world — these policies and others have helped reshape the geopolitics of the region over the past four years, and all could now be up for reconsideration by the new administration.

But it’s not clear how much room the Biden administration will have to maneuver in the region. A lot has changed in four years — some of it Trump’s doing, but most of it the result of long-term American disengagement that began with Barack Obama.

Over the past four years, the Iranian-Shiite axis anchored in Tehran but stretching deep into the Arab world, from Lebanon through Iraq and Syria and down to Yemen, has grown both stronger and weaker. It is stronger in the sense that it is more explicit and aggressive; Iranian regime institutions are more visibly pulling the strings among Shiite militias in Iraq, are more visibly arming and entrenching in Syria, and are more directly involved among the Houthis in Yemen.

But it is weaker in the sense that the militias and Iranian proxies sustaining the Shiite arc of influence have all but shattered the societies they have attempted to dominate. Wherever one looks, from Syria to Gaza to Yemen to Lebanon, and even, of course, to Iran itself, the Iranian regime has led a broad economic and political collapse. Iran’s own economy has cratered, and that’s only partly due to American sanctions. So have the economies of Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen. Iranian intervention is quickly gaining a reputation in the region as the most efficient way to decimate a society.

Then US President Barack Obama listens to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, foreground, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, November 9, 2015. (Andrew Harnik/AP)

In 2016, Obama still defended his policy of handing de facto regional hegemony to Iran by describing it as a sustainable, stabilizing Iranian-Saudi détente.

“Iran, since 1979, has been an enemy of the United States, and has engaged in state-sponsored terrorism, is a genuine threat to Israel and many of our allies, and engages in all kinds of destructive behavior,” Obama told Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic at the time. “And my view has never been that we should throw our traditional allies [the Saudis] overboard in favor of Iran,” he affirmed.

But.

The Saudis, Goldberg writes in describing Obama’s view, “need to ‘share’ the Middle East with their Iranian foes.”

In Obama’s words: “The competition between the Saudis and the Iranians—which has helped to feed proxy wars and chaos in Syria and Iraq and Yemen—requires us to say to our friends as well as to the Iranians that they need to find an effective way to share the neighborhood and institute some sort of cold peace. An approach that said to our friends ‘You are right, Iran is the source of all problems, and we will support you in dealing with Iran’ would essentially mean that as these sectarian conflicts continue to rage and our Gulf partners, our traditional friends, do not have the ability to put out the flames on their own or decisively win on their own, and would mean that we have to start coming in and using our military power to settle scores. And that would be in the interest neither of the United States nor of the Middle East.”

That articulated part of the deeper underlying logic of the 2015 nuclear deal, which was never only about limiting the Iranian nuclear program; it was also about deliberately empowering Iran on other fronts to enable it to act as a stabilizing force.

But it’s gotten harder over the past four years to argue that an empowered Iran would play that stabilizing role. Just ask Iraqis, Lebanese, Syrians, and Yemenis.

The Biden administration has sent moderating and, it must be said, mixed signals on its desire to return to some version of the 2015 accord. It has appointed senior officials to key roles who were among the architects of the Obama deal — and other officials to other key roles who are closer to the Israeli and Saudi view and have close contacts in the Israeli and Gulf states’ security establishments.

The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure campaign,” the Biden administration believes, has pushed Iran farther down the road to nuclear breakout. It hasn’t worked.

But the administration is still “a long way” from reentering the deal, Biden’s new intelligence chief Avril Haines told senators on Tuesday. President Biden will “have to look at the ballistic missiles you’ve identified and destabilizing activities Iran engages in,” she soothed.

Those words were echoed closely on Wednesday by Biden’s nominee for secretary of state, Tony Blinken, who assured senators that Biden was “a long way” from reentering the deal, and would not do so without first consulting with Israel and America’s Gulf allies.

Antony Blinken during his confirmation hearing to be secretary of state before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee on January 19, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Alex Edelman-Pool/Getty Images/AFP)

More importantly, Blinken gave the first serious indication that Biden views the sanctions on Iran not as a Trumpian aberration to be tossed aside, like the travel ban or border wall, but as helpful leverage the US intends to use in its coming diplomatic push.

Haines, Blinken, and others are experienced and professional diplomats. That means it can be hard to tell when they’re conveying the administration’s real policy goals, and when they’re obscuring them.

But there seems to be a realization among the new senior staff that will surround Biden that the old Obama vision of an empowered, stabilizing Iran is no longer really attainable, at least not with Khamenei calling the shots in Tehran.

Palestinian-Israeli deadlock

On the Palestinian front, there are easy and quick changes Biden is likely to make: restoring aid funding, reopening and expanding a Palestinian consulate/interest section in the Jerusalem embassy, and so on. But here, too, American policymakers will find conditions are now more resistant to American influence than in the past.

In his Senate comments, Blinken emphasized that a two-state solution was the administration’s policy but acknowledged it would be hard to advance. The comments reflect a wariness of wading into the Israeli-Palestinian morass.

Part of that wariness is rooted in the impossible juggling act of sustaining the military-intelligence alliance with Israel while imposing meaningful pressure on the Palestinian issue.

But part of it is more basic than that and has to do with the Palestinians themselves. The Biden administration is quickly staffing its top posts with veterans of the Obama years. There’s institutional memory there, including the memory of Obama’s frustration with the Palestinians’ inability to take advantage of his sympathy for their plight and willingness to impose pressure on Israel. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas proved unable to come to the negotiating table over 10 long months of an Obama-imposed Israeli settlement freeze in 2010 — a supposed trust-building measure — and that cost the Palestinian leadership a lot of credibility with Obama.

Washington is rife with advocates and activists for both sides of the conflict. But to policymakers, it’s the deadlock itself that looms largest. In practical terms, not symbolic ones, there’s no obvious path forward for a new American policy with meaningful answers for either side’s domestic politics.

Can a distracted America be trusted?

In his inauguration speech on Wednesday, Biden dedicated a short passage to the international community watching the changing of the guard in Washington.

“So here’s my message to those beyond our borders: America has been tested and we’ve come out stronger for it. We will repair our alliances and engage with the world once again. Not to meet yesterday’s challenges, but today’s and tomorrow’s challenges. And we’ll lead, not merely by the example of our power, but by the power of our example,” he declared.

The message was clear: America is back, America is reliable once more.

There’s just one problem with that assertion: It isn’t trust in Biden himself that’s being questioned around the world, but in the continuity of American policy after Biden. America has swerved radically in its policies in recent years. On Iran, for example, Obama led a dramatic break from the George W. Bush years, and Trump an equally dramatic break from Obama, and Biden, many in Israel and the Gulf fear, may preside over yet another possible break with the past.

It’s a dizzying merry-go-round for the world’s preeminent superpower. The substance of the policies is secondary to the fickleness itself. Strategic trust can’t be built on the basis of four-year American election cycles. It’s hard for allies to align themselves with American policy needs when it’s not clear America will be making the same demands just three years down the road.

That sense of whiplash from American policy polarization isn’t limited to Israel or the Middle East. It lies at the heart of Europe’s new bid for “strategic autonomy.”

But there was one issue Blinken was asked about on Wednesday in which the message of perfect continuity with the Trump years was clear and without caveat: China.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative and its profound impacts on the Middle East: China is likely to be the number one priority for the new US Administration.

In recent years, the highest levels of American strategic planning, from the Pentagon to the State Department to the intelligence community, have steadily retooled themselves for the coming global contest between America and a rising and increasingly aggressive Communist regime in China. At long last, three decades after the end of the Cold War, America faces the sort of strategic nemesis its defense establishment was built for. And that nemesis lies far from any Israelis, Palestinians, or Iranian ayatollahs.

With the rise of China, the Middle East is fast becoming a strategic footnote to the more consequential and complex faceoff further east. America’s navy may still sail the Persian Gulf, but it knows it is in the South China Sea that American strategy and influence will be tested.

It’s hard to exaggerate how dramatic a shift this represents from what came before. The Middle East is less important to American calculations, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict within it is less important still.

In 2011, Obama’s former national security advisor Jim Jones told the Herzliya conference in Israel that his ex-boss viewed the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the central issue of the Middle East, the “knot that is at the center of mass” of the region’s many conflicts.

“I’m of the belief that had God appeared in front of President Obama in 2009 and said if he could do one thing on the face of the planet and one thing only, to make the world a better place and give people more hope and opportunity for the future, I would venture that it would have something to do with finding the two-state solution to the Middle East,” Jones said.

It’s hard to find senior officials in Washington who would now venture such an assertion.

Israeli and Saudi officials are bracing for a Biden pivot on Iran. So are Iranians. Palestinians now expect an American restoration of ties and support severed under Trump. The region is holding its breath as it waits to learn what the new administration intends to do.

But Biden’s options are exceedingly limited, and for good reasons. American influence is harder to assert in a region increasingly uncertain about America’s reliability. America has larger adversaries and more significant geopolitical concerns elsewhere. And the Middle East now offers less potential return on the investment of political capital than it arguably did four or 12 years ago.

Biden will have trouble effecting meaningful policy shifts in the region, and, early administration statements suggest, appears uninterested in investing too much effort in the attempt.

Biden’s First 200 Days: The Security Agenda

Many of the administration’s early Middle East security efforts will boil down to crisis management, but new frameworks like the Abraham Accords may provide opportunities to address longer-term problems.

The US military’s central command, encompassing the Middle East, must become more adept at limited uses of force, as the US seeks to intelligently manage the insoluble problems that plague the region.

The Biden administration’s national security team may be tempted to focus on potential early tests by foreign adversaries, urgent matters demanding immediate attention, and potential “quick wins” such as strengthening and lengthening the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, building on and expanding the Abraham Accords, and consolidating the Gulf Cooperation Council reconciliation process. Certainly, it should do all these things. But in its first 200 days, it also needs to fundamentally rethink how the United States can advance its interests in a conflict-prone region located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa, as it increasingly turns its attention to the Indo-Pacific region and other parts of the world.

The Middle East’s most vexing problems cannot be “solved”—at least for now; crises will need to be “managed.” Seeking to freeze conflicts or play the role of spoiler may lack appeal to U.S. policymakers used to playing the role of regional peacemaker or hegemon, but these alternative policy approaches can halt humanitarian disasters and deny victory to adversaries. In many cases, that will be good enough. And the United States must become more adept at the limited use of force in circumstances well short of war; that will, unfortunately, remain necessary in the Middle East. Policymakers need a vocabulary and mental models more appropriate to “by, with, and through” and gray zone operations in order to advance U.S. interests with a light force footprint, in ways that bolster diplomacy but do not roil a war-weary public back home. They likewise need to rethink how the United States trains foreign militaries, in order to build partner forces capable of bearing their share of the defense burden. And the United States needs to launch a missile defense Manhattan Project to develop the means to defeat the main asymmetric capability possessed by U.S. adversaries in the Middle East and elsewhere.

The roots of many of the region’s conflicts are structural and cultural: large youth bulges; rapid urbanization; extreme gender hierarchies; destructive governance models; conflict-prone honor cultures and super-charged asabiyas (social solidarities). All of these are risk factors for instability, violence, and state failure that interact in often subtle and harmful ways, and that are exacerbated by stressors such as climate change and environmental degradation. Addressing these looming challenges will require long-term approaches that transcend the traditional policy toolkit. The Abraham Accords, however, may offer a first step toward the kind of regional and global partnerships necessary to better manage the Middle East’s present conflicts and address its future water and food security, public health, and climate challenges. Let’s get to work!

Michael Eisenstadt is the Kahn Fellow and director of the Military and Security Studies Program at The Washington Institute. This article was originally published as part of a Middle East Institute series on Biden’s first 200 days. It also previews the author’s Transition 2021 memo on America’s regional military posture, soon to be published by The Washington Institute.

Biden doesn’t need to rush back into the Iran nuclear deal to defuse tensions

In this picture released by the official website of the office of the Iranian supreme leader, worshipers chant slogans during Friday prayers ceremony, as a banner shows Iranian Revolutionary Guard Gen. Qassem Soleimani, left, and Iraqi Shiite senior militia commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, who were killed in Iraq in a US drone attack on Jan. 3, and a banner which reads in Persian: ‘Death To America,’ at Imam Khomeini Grand Mosque in Tehran, Iran, Friday, Jan. 17, 2020 (Office of the Iranian Supreme Leader via AP)

Iran has resumed enriching uranium to 20 percent in its secretive Fordow facility, which is literally built inside a mountain. Enrichment to this level puts Iran in a position where getting to weapons-grade fissile material is not a big leap. It is certainly the most problematic of all the Iranian breaches of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the Iran nuclear deal.

Why is this happening now? Iran has clearly decided to build pressure on the incoming Biden administration, conveying, in effect, that whatever its priorities, it had better deal with the Islamic Republic soon. As if to punctuate their determination to be a problem that must be addressed, the Iranians also seized a South Korean-registered ship in the Strait of Hormuz.

The Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal and application of maximum economic pressure clearly did not succeed in changing Iran’s behavior but certainly did succeed in doing great damage to the Iranian economy. Iran needs sanctions relief and wants the United States to fulfill its obligation under the JCPOA to lift all nuclear-related sanctions.

With President-elect Joe Biden having already said he will seek to rejoin the JCPOA, aren’t the Iranians pushing on an open door? Not really, because the president-elect’s position is compliance for compliance, meaning that we cannot lift sanctions before the Iranians are back in compliance — and by most estimates, it will take the Iranians a few months to do so.

(Getting back into compliance is not like flipping a switch; to give just one example, Iran has accumulated more than 2,400 kilograms of enriched uranium, nearly 12 times the amount permitted in the JCPOA, and it will take time to export or dilute it.)

In addition, the Iranians are demanding compensation for what the sanctions have cost them and insisting that the United States, not Iran, must act first. Note that the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei recently emphasized that the West is obliged to lift sanctions immediately, while also declaring that “we are in no rush for the U.S. to return to the JCPOA. This is not the issue for us. … If the sanctions are not lifted, then the U.S. return to the JCPOA might even be to our disadvantage. … Of course, if they return to their commitments, we will return to ours.”

In other words, the onus is on us, and Iran’s provocative actions are designed to get the incoming Biden administration to defuse the problem by giving Iran sanctions relief before anything else is done. While Biden might be open to providing humanitarian and medical supplies, his compliance for compliance signals that sanctions relief is not possible so long as Iran is violating the JCPOA.

One way to break the impasse and make a virtue of necessity would be for the administration to shift the focus from rejoining the nuclear deal following Iran’s return to full compliance to a “less for less” deal: The United States provides limited sanctions relief; Iran scales back where it is not in compliance. For example, in return for halting enrichment to 20 percent, reducing its stockpile of low enriched uranium from more than 2,400 to 1,000 kilograms and for dismantling its cascades of advanced centrifuges, we permit Iran access to some of their frozen overseas accounts.

Veteran US official Amb. Dennis Ross, who served as President Obama’s “special assistant” on Iran: “It might make sense not to rejoin the nuclear deal”

There would be several benefits to such a “less for less” deal: It would scale back the Iran nuclear program in a way that would extend its breakout time and make it less threatening; it would maintain our overall sanctions regime, thus preserving our leverage; it would buy time to try to achieve the longer-term agreements that the president-elect seeks, which he hopes on the one hand will extend the sunset provisions in the nuclear deal and on the other produce parallel understandings on ballistic missiles and Iran’s regional behavior; it would make it far easier to gain some Republican buy-in given their almost uniform opposition to the JCPOA, even as it would reduce the Iranian nuclear threat Trump is leaving. Finally, it would be more likely to reassure the Israelis, Emiratis and Saudis who fear an early return to the deal, and the lifting of all nuclear-related sanctions will give the Iranians little reason to change their threatening regional behavior.

Negotiations are never easy with the Iranians. If, however, the Biden administration wants to produce follow-on negotiations that will require more from the Iranians while also giving them more in terms of economic benefits and not just sanctions relief — something that will require congressional support — it might make sense not to rejoin the nuclear deal. In other words, if we are to get to “more for more,” we need to start with less for less.

Dennis Ross, a former special assistant to President Barack Obama, is the counselor and William Davidson distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute.

Tags: