UPDATES

Another indecisive Israeli election outcome

March 26, 2021 | AIJAC staff

Update from AIJAC

03/21 #04

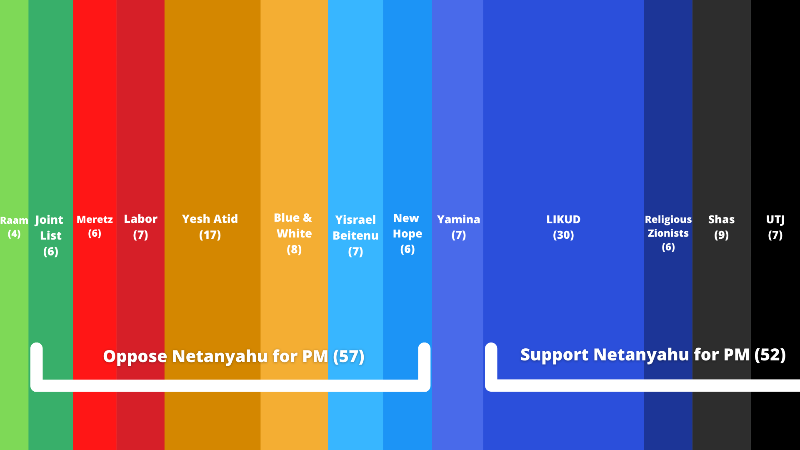

Israel voted yet again on Tuesday for the fourth time in two years – and as the diagram above illustrates, the final results do not look much more likely to break the long-standing political impasse than the outcomes after the last three trips to the ballot box. This Update looks at the election results, their implications, and what might happen next.

We lead with the Times of Israel’s summary of the result for the two antagonistic blocs of parties – one in support of current PM Binyamin Netanyahu remaining in office finishing with 52 seats, another opposed to this with 57 seats, and two “swing parties” with seven and four seats respectively. The piece reviews what various key party leaders have said about the outcome and what they intend to do next, and what happens now under Israeli law. It also reviews some debate in the pro-Netanyahu bloc about the controversial possibility of relying on the small Islamist Ra’am party to get a majority. For all the basics of where Israeli politics is now, CLICK HERE.

A more analytical discussion of the lessons of this election comes from veteran Israeli journalist and commentator Shmuel Rosner (who incidentally will be AIJAC’s guest at a webinar about the election next week). He reviews the debates regarding Netanyahu’s legal situation and corruption charges, the secular-Orthodox split in Israel, and the changing role in Israeli politics for predominantly Arab political parties – like Ra’am mentioned above. He also points out that, despite these divisions, there remains a strong consensus in Israel on issues related to foreign affairs and defence. For all the insights from this canny observer of the Israeli political scene, CLICK HERE.

Finally, an opinion column from Times of Israel editor David Horovitz expresses the deep frustration of many Israelis at the political impasse. He calls the current situation surreal and says it looks like only an “ideologically super-illogical amalgamation of strange political bedfellows can spare us from yet a fifth round of elections.” He also offers some additional interesting insights into the ironies of the political alignments which have emerged since Tuesday, as well as discussing some policy implications. For all of his analysis and passionate opinion, CLICK HERE.

Readers may also be interested in…

- Another discussion of the numerous ways this election looks likely to redraw the political map, from Tovah Lazaroff of the Jerusalem Post.

- A Jerusalem Post editorial calling for a national unity government to prevent a fifth election.

- Legal reporter Yonah Jeremy Bob discusses the implications of a plan being mooted by anti-Netanyahu parties to pass a bill that would bar Netanyahu from running the government while under indictment, and which could potentially be passed without uniting to form an alternative government.

- A call for electoral reform in Israel to prevent political logjams like the current one from columnist and past AIJAC guest Emily Schrader.

- Some examples from the many stories and comments now appearing at AIJAC’s daily “Fresh AIR” blog:

- AIJAC’s Jeremy Jones speaks on ABC Radio on Harmony Week, Racism and Multiculturalism in Australia.

- AIJAC Research Associate Dr. Ran Porat reports that an Australian Arabic language newspaper is claiming Israel sent prostitutes to entice Gulf states to normalise relations.

- Ran Porat also had an analysis of the Israeli election outcome on The Conversation.

4th time’s not the charm: With all ballots tallied, Netanyahu again falls short

Final election results leave no clear path to coalition; anti-Netanyahu bloc has 57 seats, pro-PM bloc has 52; Yamina (7), Ra’am (4) hold balance

By TOI STAFF

Times of Israel, 25 March 2021

Incumbent PM Benjamin Netanyahu campaigned hard yet again, but the results still do not leave him with any clear path to a parliamentary majority (Credit: Gali estrange / Shutterstock.com)

With all votes counted Thursday evening, results showed Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had failed, for the fourth time in a row, to win a clear parliamentary majority. The results left both the premier and his political opponents once again without a clear path to forming a coalition government, and heralded enduring gridlock and a potential fifth election.

The Central Elections Committee said all absentee votes had been counted. Official results will be presented to President Reuven Rivlin next Wednesday, and the CEC formally noted there was a possibility of change until then — but this was widely seen as unlikely.

Netanyahu’s right-wing and religious backers had 52 seats while parties opposed to the premier had 57 between them. The right-wing Yamina party (with 7) and Islamist Ra’am (with 4), have not committed to either side.

Netanyahu would need both parties to achieve a slim majority, but cooperation between the far-right and Ra’am’s Islamists appeared all but impossible.

Meanwhile, a potential “change coalition” of Yesh Atid, Blue and White, Yamina, Yisrael Beytenu, Labor, New Hope and Meretz would have 58 votes, also three short of a majority.

With the final results, New Hope party leader Gideon Sa’ar, who quit Likud to challenge Netanyahu from the outside, but whose party eventually won only 6 seats after once polling at over 20, called to examine all options for forming a government without Netanyahu.

“It is clear that Netanyahu doesn’t have a majority for a coalition headed by him,” he said in a statement. “Now we must work to fulfill the potential for forming a government of change. As I announced on election night, ego won’t be a factor.”

Israeli President Reuven Rivlin will receive the official election results next Wednesday, and then begin the process of interviewing party heads before deciding who to entrust with a mandate to form a government (Photo Credit: paparazzza / Shutterstock.com)

Yesh Atid leader Yair Lapid and Labor chief Merav Michaeli met Thursday evening to discuss the election results.

The two “discussed potential cooperation to build a change coalition and replace Netanyahu,” according to a joint statement. “Further conversations will be held.”

Likud, in a statement, said: “The ‘change bloc’ is a whitewashed name for an anti-democratic bloc. The only real change they want is to bring laws that exist only in Iran to limit candidates and to annul the democratic votes of over a million Israeli citizens.”

The party appeared to be referring to talk in the opposition of legislation to prevent Netanyahu, as a person on criminal trial, from forming a new government.

Sa’ar, a former Likud minister, was being urged by Netanyahu allies Thursday to renege on his central election promise of not joining Netanyahu’s bloc.

MK Bezalel Smotrich, head of the far-right Religious Zionism party, called on Sa’ar and Yamina’s Naftali Bennett to “put personal matters aside and enter a right-wing government.”

“They can and should set… demands that will make this government truly right-wing — in law, settlement, security, Jewish identity, expulsion of infiltrators, the economy, and more. Religious Zionism will of course back them up with these demands, and I am convinced that so will the ultra-Orthodox parties,” Smotrich said.

Netanyahu is also likely to focus on members of Sa’ar’s New Hope, most of them former Likud MKs, as he searches for potential “defectors” who could yet get him past the finish line to the coveted 61 seats.

Bennett has refused to rule out sitting in a government with Netanyahu, though he campaigned on the declaration that it was time for a change in leadership.

Smotrich ruled out any parliamentary cooperation with Ra’am Thursday, further narrowing Netanyahu’s options.

“There will be no right-wing government based on Mansour Abbas’s Ra’am party. Period,” Smotrich wrote on Facebook. “The irresponsible voices of some right-wing elements in recent days who support such reliance… reflect dangerous confusion. Friends, get this out of your head. It will not come about, not on my watch.”

The comments came after a report said Netanyahu has not ruled out “parliamentary cooperation” with Ra’am.

On Wednesday, both Ra’am and Smotrich’s far-right faction partner Itamar Ben Gvir ruled out joining forces with each other in a coalition.

Ra’am could potentially put either side over the 61-seat mark for a majority, but right-wing politicians, both in the pro-Netanyahu bloc and the anti-Netanyahu camp, have ruled out basing a coalition on the party’s support, due to what they say is its anti-Zionist stance.

Netanyahu himself has repeatedly ruled out sitting with Abbas in a coalition, saying that Ra’am was no different from the Arab-majority Joint List alliance — long considered a political pariah due to some of its members’ non-Zionist and anti-Zionist views.

Abbas’s movement is the political wing of Israel’s Southern Islamic Movement; like Hamas, it is modeled on the Muslim Brotherhood. Abbas has in the past praised aspects of Hamas’s 2017 charter, although he also criticized the document for not ending the targeting of Israeli civilians by the terrorist group.

Israeli Elections: Initial Lessons

Shmuel Rosner

Jewish People Policy Institute, 25/3/21

Israelis who have just gone to the polls for the fourth time in two years are now contemplating the possibility of yet another poll later this year if the apparent post-election deadlock is not broken (Photo credit: Roman Yanushevsky / Shutterstock.com)

The most recent Israeli elections, like all election campaigns, can be analyzed on the tactical, short-term level or in regard to longer-term trends. On the tactical level, the elections did not result in a decisive victory to any of the political camps. This deadlock could lead to a fifth election cycle, or alternately, to the piecing together of an ideologically incoherent coalition, that will, therefore, not have a strong chance of surviving long.

In a series of political moves, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu succeeded in splitting his rival camp. But the outcome remained similar to the results of the previous elections and did not provide a clear winner (at time of writing, the results have not yet been finalized). When examining long-term trends, this election seems like a continuation of its predecessors. Israel is stuck in a near stalemate between the two political camps, divided along what seems to be a personal issue, but is actually much deeper. The question is whether Netanyahu can continue to serve as prime minister.

The legal situation is clear: Netanyahu can continue to serve, even though a number of indictments have been filed against him for corruption. Netanyahu’s supporters hold strong to this fact and claim that challenging Netanyahu’s legitimacy is only a political move employed by those who do not have enough support to win an election against him. Netanyahu’s opponents claim that most of the public is not interested in continuing his tenure of office (as public opinion polls show), and therefore, negating his legitimacy is justified.

The socio-political situation is more complex: in order to decipher its implications, it is helpful to look at voters according to alternative prisms to the main one used in the elections, of who is for or against Netanyahu’s continued service as prime minister, and focus on other characteristics of these voters. These reveal some truths about these voters that do not change significantly from election to election, even if tactical changes in how votes are cast lead to new political possibilities.

When dividing according to the classic right-left paradigm, in relation to foreign affairs and defense, nearly 60 percent of the electorate voted for parties that can be classified as “right-wing.” This is not surprising. The positions of the Israeli public on these matters (Iran, Lebanon, Hamas, the Palestinian issue, settlements, etc.) are stable and well known. Roughly 60 percent of the Jewish public self-identifies as “right” or “center-right.” Even a significant number of “centrist” voters (about a quarter of Jewish voters) do not offer a practical alternative to the policies set by the Israeli government on these issues in recent years.

When dividing according to religiosity, nearly 20 percent of the electorate voted for parties on the conservative end of the spectrum. Thus, Shas and United Torah Judaism voters, and the Religious Zionist party, represent voters with a very Orthodox worldview in the religious sense, and a very hawkish worldview on issues relating to the Israeli-Arab conflict. To these, we can add another group that comprises roughly 4 percent of voters who voted for Ra’am, whose positions on many issues, such as family values, religion and state, the LGBTQ community and others, are similar to the ultra-Orthodox parties in Israel.

Its important to point out that despite significant public anger at the “Haredim” due to the conduct of groups within the sector during the Covid crisis (not following the rules, active opposition to government instructions, etc.) – anger that is expressed in public opinion polls and rhetoric on social media and in other political arenas – their ability to influence political developments through their representatives was not harmed. Practically, it may very well be that the political stalemate, which makes it harder for Netanyahu and his rivals to put together a coalition, only empowers them.

It should be noted that the party that ran a primarily “anti-Haredi” campaign (Yisrael Beitenu – Avigdor Lieberman) won fewer mandates in this election cycle compared to previous ones. Yisrael Beitenu’s weakening might not have been caused by this campaign, but the fact that it did not excite the public and attract additional voters could affect the strategy taken by party leaders in future elections in relation to the Haredi challenge.

Avigdor Lieberman of the Yisrael Beitenu party ran a campaign with an anti-ultra-Orthodox theme, yet failed to capitalise on growing anger at the ultra-Orthodox over the flouting of COVID restrictions by elements of that population (Photo credit: David Cohen 156 / Shutterstock.com)

When dividing the electorate into Arabs and Jews, the 2021 elections once again demonstrated the difficulty of Arab-Israeli voters to gain political representation proportionate to their population share, as well as the practical difficulty of leveraging this representation to influence policy. However, the split in Arab voters in this election could point to a gradual shift in the Israeli-Arab approach to the Israeli political arena. The Ra’am party led by Mansour Abbas announced prior to the elections that it would not rule out any possible coalition partners, including those from the right. This announcement indicates a desire to influence the political system from within, through political bargaining aimed to look after the interests of Israeli-Arab voters. This approach would require conceding the usual agenda of Arab parties, who are viewed by the public (at times justified and at other times less so) as being more concerned with “Palestinian interests” of non-Israelis than those of their actual voters.

In this context, after it became obvious that these elections resulted in another stalemate, even strongly right-wing parties, who have at times employed harsh rhetoric against the Arab minority in Israel (especially the “Religious Zionists”), began speaking differently about the possibility of entering a coalition with an Arab party (or at least the possibility of some kind of a limited joint action in relation to legislative processes in the Knesset).

The fact that a Likud prime minister has not ruled out, and may even require, political partnership with an Arab party – which at least some of his far-right partners are willing to consider – is without a doubt one of the most significant developments of this election. It is clear that the political system is moving toward this possibility, mostly for electoral considerations, which some have called “cynical.”

However, one should not underestimate the conceptual shift and the significance of the Israeli public’s openness to greater involvement of Arab parties and Knesset members in the political lives of all Israelis. This development should be taken into consideration when examining the overall significance of the current political stalemate. On one hand, this sharpens a number of tensions and highlights deep divisions between groups in Israeli society, but on the other hand, it accelerates surprising societal processes that could bring about positive long-term change.

Another important division is between parties seeking to implement significant reforms to the judicial system, and limiting the power of the Israeli Supreme Court, and those who strongly oppose this. For this division, it is appropriate to point out three main camps: those who want deep reform, those who want careful and gradual reform, and those opposed to any reform (and who would characterize reform as “damaging the justice system”). According to the election results, the “deep reform” camp does not hold a majority among the voting public. But when taken together with those who favor cautious reform, the two groups in combination certainly form a majority. One can predict that if Netanyahu manages to put together a coalition, it will attempt to bring about some kind of judicial reform. This could include a variety of moves, from changing the authority of the attorney general, to limiting the Supreme Court’s power to overturn Knesset legislation.

To sum up: there is no doubt that that the fact Israel is once again finding it difficult to put together a governing coalition that would offer political stability is problematic, to say the least. The question is whether the post-election negotiations will lead to a temporary solution that will move the political system forward, or if Israel will be dragged to a fifth election cycle in under three years. On the positive side, its worth mentioning that despite the ongoing political challenge, the Israeli voting public remains relatively disciplined, and the election was conducted in an orderly fashion. Israel’s democracy may be stuck in the throes of indecision, with no clear outcome, but at this stage, this distress does not seem to endanger the main systems of governance.

Shmuel Rosner is a Tel Aviv-based columnist and editor and a senior fellow at The Jewish People Policy Institute (JPPI).

Israeli politics has now moved from farcical to surreal; insanity is looming

Our electoral system is dysfunctional; our democracy is holding firm, for now

By DAVID HOROVITZ

Times of Israel, March 26

After three previous elections, voter turnout was down at Israeli polling places on Tuesday – and what the voters who did turn up had to say does not offer much hope that the political logjam will be broken anytime soon (Photo Credit: Roman Yanushevsky / Shutterstock.com)

Forty-six hours after polling stations closed, Israel’s election results were finally announced Thursday night, and what an ongoing broch [A Yiddish word meaning disaster, ed,] they add up to.

Voter turnout was way down — from 71.5 percent a year ago to 67.2 percent on Tuesday. The distribution of seats was significantly different from predictions in both pre-election surveys and in the 10 p.m. exit polls on Tuesday night. But the big picture is all too familiar: the Israeli electorate has conjured up yet another non-definitive result.

The pro-Netanyahu camp has 52 of the 120 Knesset seats. The anti-Netanyahu camp has 57. Naftali Bennett’s Yamina, possibly inclined toward Netanyahu, has 7. And the great election confounder, the conservative Islamic Ra’am party — which not one of the three ostensibly ultra-accurate TV exit polls predicted would make it into the Knesset — has 4.

That means neither the pro- nor anti-Netanyahu alliances have a clear path to a majority, and only some kind of ideologically super-illogical amalgamation of strange political bedfellows can spare us from yet a fifth round of elections mere months from now.

A surreal coalition of an Arab party and an anti-Arab party, both anti-LGBT?

The prospect of one such surreal mis-alliance has already risen and fallen, though it may yet rise again:

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu repeated time and again in the final weeks of the campaign that he would never include Ra’am in a coalition he leads, nor even rely on its support from outside for a majority. “Out of the question,” he told Channel 12 news last week, branding Ra’am’s leader Mansour Abbas an anti-Zionist. Yet as the results were tallied, and it became clear that Ra’am’s support could lift a Likud-led coalition to the magical 61-seat minimal majority total, several of Netanyahu’s Likud colleagues, including a senior minister, began publicly musing that perhaps Ra’am, hitherto an enemy of the state, was not beyond the pale after all.

And thus on Wednesday, the Israeli electorate was asked to contemplate the mindblowing possibility of Netanyahu — the leader who campaigned on the promise to build a “full right” government, and who savaged challenger Benny Gantz last year for so much as contemplating constructing a coalition reliant on Arab MKs — seeking to govern with the parliamentary backing of both Arabs and pretty virulent anti-Arabs: He would have Ra’am on one flank, and, on the other, the far-right Religious Zionism party, complete with its racist Otzma Yehudit component that seeks to expel “disloyal” Arabs. These two beyond-implausible partners do have one thing in common, however: their anti-LGBT stance. So we were also looking at a coalition featuring two anti-LGBT parties and a senior minister who is gay — Netanyahu loyalist Amir Ohana.

As of this writing, Netanyahu has neither ruled in nor ruled out a possible reliance on Ra’am, his pre-election dismissal notwithstanding. But Religious Zionism’s leader Bezalel Smotrich, and his Otzma Yehudit colleague Itamar Ben Gvir, emphatically intervened on Thursday morning. “Not on my watch,” said Smotrich.

And thus that route to Netanyahu’s reelection would appear to have been blocked off. Unless or until it is revived again.

Partnering with a PM who abandoned his previous unlikely partner?

In his non-victory speech early Wednesday morning, the prime minister did not reach out to Ra’am. Rather, he pleaded with erstwhile allies who are now in the anti-Netanyahu camp to rejoin him, and thus to spare Israel yet a fifth election.

This constitutes another unlikely gambit, since Israel was sentenced to this fourth vote because Netanyahu refused to pass the state budget, and the Knesset automatically dissolved, precisely so that he could escape his solemnly signed commitment to hand over the prime ministership to Gantz this coming November. Essentially, therefore, he is now appealing to Gantz and anybody else in the Zionist anti-Netanyahu camp to do exactly what he persuaded Gantz to do so self-defeatingly less than a year ago.

A potential coalition partner? Mansour Abbas of the Islamist Ra’am party looks positioned to play kingmaker – and Netanyahu has been saying contradictory things about partnering with him. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons | License details)

Will Gantz again save Netanyahu’s skin? Having defied the political gravediggers and won eight seats, the Blue and White leader is, as ever, pledging to “put Israel first.” In contrast to last year, however, he now insists that this commitment requires ousting rather than rescuing Netanyahu, who he says he’s concluded is a manipulator and a liar.

Will Yamina’s Bennett help Netanyahu stay in office, for that matter, when the prime minister did everything in his considerable campaigning powers to win over Bennett’s voters in the final stretch of the race? Bennett, too, has publicly stated that Netanyahu cannot be trusted. And he would be sitting in government with Ben Gvir, with whom he has refused to ally in the past, and who even Netanyahu, as recently as last week, said could have no place in his government.

Might Netanyahu successfully woo Knesset members from the ranks of ex-Likud minister Gideon Sa’ar’s New Hope, which performed so far below earlier expectations in winning just six seats? Sa’ar and his party colleagues, who say Netanyahu’s emissaries have already come calling, are adamant that this will not happen.

Any potential defectors, from Sa’ar’s party or elsewhere, would not merely be abandoning the anti-Netanyahu camp, but also joining forces with the Religious Zionism party, a radical alliance that is deeply hostile to non-Orthodox Judaism, whose leader would like to see Israel run according to the laws of the Torah, and which includes not only the Meir Kahane disciple Ben Gvir, but also a representative of the viciously anti-LGBT Noam movement.

All this to enable the ongoing governance of a prime minister they know cannot be trusted to honor political agreements; who is also on trial for corruption; who failed to achieve a decisive election win even after spearheading a world-beating COVID-19 vaccination campaign; and whose capacity to sustain such an improbable coalition would appear to be extremely slim — meaning they could have to face an increasingly irate electorate again all too soon.

In the anti-Netanyahu camp, efforts are in full swing to establish very different coalitions — helmed by Lapid, or by Lapid in rotation with Sa’ar, or by Bennett. All the various permutations would require ideological opposites backtracking on solemn commitments. None of the possibilities is straightforward; none of them offers a clear prospect of political stability.

But the alternative remains the almost unthinkable resort to more elections; what was that cliché about the definition of insanity?

No majority for radical reform of the judiciary

Dismally, Israel has been hamstrung by political crisis since way back in December 2018, when the Knesset dissolved ahead of the April 2019 elections. But its politics have not been paralyzed. These latest inconclusive elections saw Sa’ar break away from Likud, and Bennett directly challenge Netanyahu — rivals from his own side of the spectrum that rendered Tuesday’s vote the closest yet to a pure referendum on the prime minister, with forces left, right and center all vying to oust him.

He’s not finished yet, but neither was he victorious, despite the vaccination success, which enabled the electorate to cram the supermarkets, beaches and restaurants on election day.

Moreover, his legal complications have only deepened as the electoral deadlock extended. The evidentiary stage of his corruption trial begins on April 5, the day before our newest splintered parliament is sworn in.

Though Netanyahu insists he has no intention of trying to evade his trial, members of his own Likud and of Religious Zionism promised during the campaign to initiate legislation designed to suspend his prosecution for as long as he is prime minister.

However the coalition negotiations play out in the coming weeks, it seems clear that there is no majority in the new Knesset for legislation of that nature, or for a wider reining-in of judicial authority, tailored to Netanyahu’s interests, fundamentally remaking Israel’s separation of powers.

Claiming that the charges against him have been fabricated, Netanyahu has relentlessly castigated the police and the state prosecution, trying to discredit Israeli law enforcement. Demonstrations against the prime minister, demanding his resignation, have frequently turned confrontational, featuring clashes with police and several instances of attacks by pro-Netanyahu counter-protesters. The election campaign was marred by disruptions, including by Likud activists targeting Sa’ar. The prime minister’s son posts endless inflammatory material on social media.

Israel knows all too well about the dangers of political violence; thus far, the worst excesses have been avoided.

Four inconclusive votes in less than two years, with no state budget and a crippled parliament, would indicate that our electoral system is dysfunctional. For now, at least, the pillars of our democracy are holding firm.