FACT SHEETS

RESOURCES

Fact Sheet: The European invocation of the JCPOA “dispute resolution” mechanism

January 17, 2020 | AIJAC staff

On January 14, Britain, France and Germany, three key signatories of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) nuclear deal reached with Iran in 2015, invoked the Dispute Resolution Mechanism (DRM) in that agreement.

Here is our guide to what this means and what could happen next.

What did the Europeans say?

The statement (January 14) was issued by the foreign ministers of the three European signatories to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – France, Germany and the UK. It said:

- That they had determined that Teheran is in breach of the agreement and has no acceptable rationale for doing so: “Iran has continued to break key restrictions set out in the JCPOA. Iran’s actions are inconsistent with the provisions of the nuclear agreement and have increasingly severe and non-reversible proliferation implications… We do not accept the argument that Iran is entitled to reduce compliance with the JCPOA” because of the US withdrawal from the deal in 2018.

- The three nations said they were invoking the JCPOA procedure that can lead to the reimposition of UN sanctions against Iran – “We have therefore been left with no choice, given Iran’s actions, but to register today our concerns that Iran is not meeting its commitments under the JCPOA and to refer this matter to the Joint Commission under the Dispute Resolution Mechanism, as set out in paragraph 36 of the JCPOA.”

What happens now?

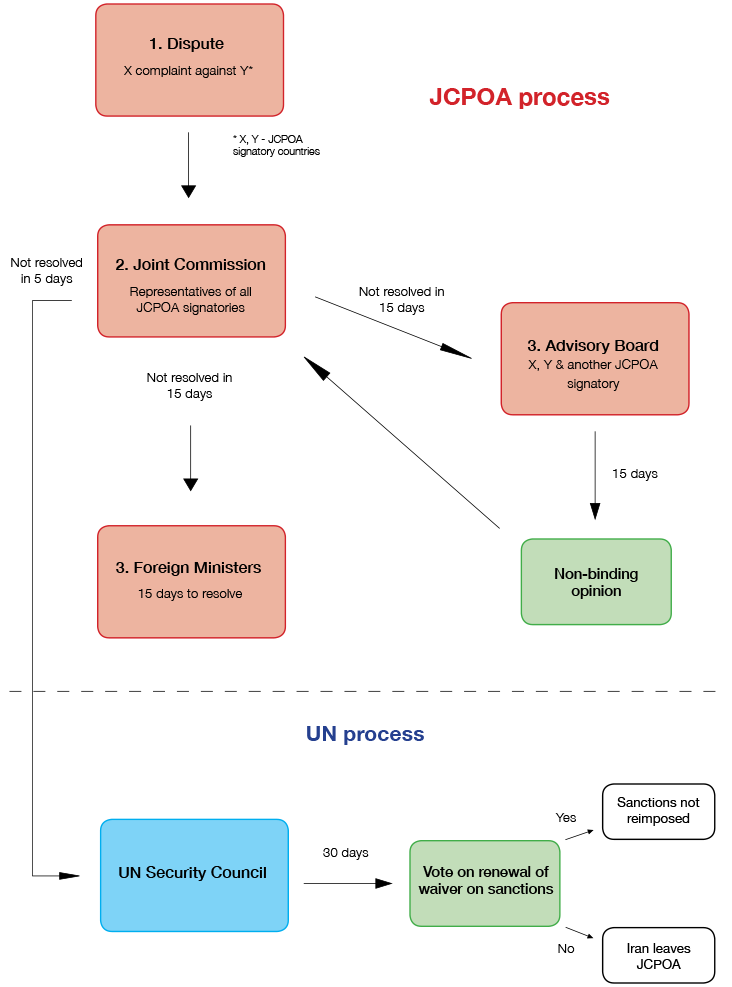

The Dispute Resolution Mechanism is a long procedure built into the JCPOA with several steps of 15 days each (unless extended by consensus) for reviewing disagreements about implementation and compliance with the deal. If no resolution is reached at the end of this process, any signatory of the JCPOA can invoke a process to “snapback” the UN sanctions on Iran, which were suspended but not lifted under the JCPOA.

What are the stages of the DRM?

Any JCPOA signatory, Iran included, which believes other parties are not meeting their agreement obligations, can refer the issue to the Joint Commission, which consists of all countries party to the deal (Iran, the UK, France, Germany, China and Russia – the US was a party but withdrew from the deal in May 2018).

If the Commission fails to resolve the dispute within 15 days, any party can refer the matter to be debated for an additional 15 days amongst the ministers of foreign affairs of the parties. At the same time, the issue can be discussed by a 3 member Advisory Board, consisting of a representative of each of the parties in dispute plus a representative of a third country. The Advisory Board is required to issue a non-binding opinion within 15 days.

The Joint Commission then has 5 days to try to resolve the dispute based on the Advisory Board’s advice. If this process fails, the complaining party can choose to report the issue to the UN Security Council (UNSC) as a “significant non-performance”, meaning a breach of the deal.

As noted, at any point, the timeline can be extended by a consensus of the parties.

How can the Security Council “snapback” sanctions on Iran?

After a “non-performance” report, the Security Council is asked to vote on whether to continue with the suspension of the UN-mandated sanctions against Iran. In diplomatic language, the UNSC would be voting on whether or not to renew the waivers on implementing the various UNSC Resolutions (2006-2015) imposing sanctions on Iran.

If the UNSC does not vote to renew the waiver within 30 days, all UN sanctions would be re-imposed unless there is a new UNSC Resolution which contradicts this.

This means that, once such a referral to the Security Council occurs, any of the permanent UNSC member states can effectively enable “snapback” of the sanctions by vetoing any resolution for renewing the waivers. This is particularly relevant to the US, which calls for the JCPOA to be replaced with a new deal, and has been imposing its own very heavy sanctions on Iran since abandoning the agreement (May 2018) under a policy of “maximum pressure” designed to force Iran to return to negotiations on a different, more comprehensive and more watertight deal.

What would the “snapback” of sanctions mean for the JCPOA?

Under a clause in the JCPOA, snapback would signal the end of the agreement, with Iran entitled to stop fulfilling its obligations under the deal. Clause 27 of the JCPOA says “Iran has stated that if sanctions are reinstated in whole or in part, Iran will treat that as grounds to cease performing its commitments under this JCPOA in whole or in part.”

Why did the EU make this announcement now?

While there have been accusations about Iran violating various JCPOA provisions previously, since May 2019, Iran has made a series of open announcements about taking actions violating key provisions of that agreement. These actions, apparently designed to force the Europeans to do more to compensate Iran for US sanctions, have been confirmed by inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

By late last year, after four such announcements, Iran was exceeding the stockpiles of enriched uranium it’s allowed to have under the JCPOA; was exceeding the levels of purity of enrichment the JCPOA allows; was employing advanced centrifuges to enrich uranium even though this is prohibited by the JCPOA; and had begun injecting uranium into centrifuges at the Fordow facility, which it is not allowed to use for uranium enrichment under the JCPOA’s terms.

Then, following the US killing of senior Revolutionary Guard commander General Qassem Soleimani on Jan. 3, the Iranian government announced that it would “continue its nuclear enrichment with no restrictions,” implying a total repudiation of the JCPOA limits on enrichment.

European states had protested previous Iranian announcements of JCPOA violations but had insisted that the Iranian steps were reversible, and the JCPOA was still valuable and they remained committed to it.

Apparently, the three European state parties to the JCPOA have now come to the conclusion that these measures have gone so far that their policy of simply protesting verbally is no longer tenable. As their statement invoking the DRM says, Iran’s moves away from the JCPOA now have “severe and non-reversible proliferation implications.”

However, US pressure may also have played a role. News reports say the Trump Administration may have recently threatened privately to impose tariffs on European automakers if the European JCPOA signatories did not toughen their stance on Iran’s ongoing violations.

Nonetheless, the announcement by the three European states was very keen to stress that these moves were intended to save the JCPOA, and not join the US policy of seeking to scrap and replace it via “maximum pressure”. As UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab told the House of Commons: “The UK, France and Germany will remain committed to the deal and will approach the DRM in good faith, striving to resolve the dispute and bring Iran back into full compliance with its JCPOA obligations.”

Given this, it remains to be seen if Paris, Berlin or London will actually be willing to bring the dispute to the UN Security Council, thus potentially triggering snapback and a collapse of the deal, even if the DRM process does nothing to return Iran to compliance.

However, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson did apparently signal that his government was reconsidering its until now iron-clad commitment to the JCPOA, telling the BBC that replacement of the current deal with a “Trump deal” might be a way out of the current impasse.