IN THE MEDIA

The real legacy of the controversial Balfour Declaration

November 11, 2017 | Gareth Narunsky

Bangkok Post – 11 November 2017

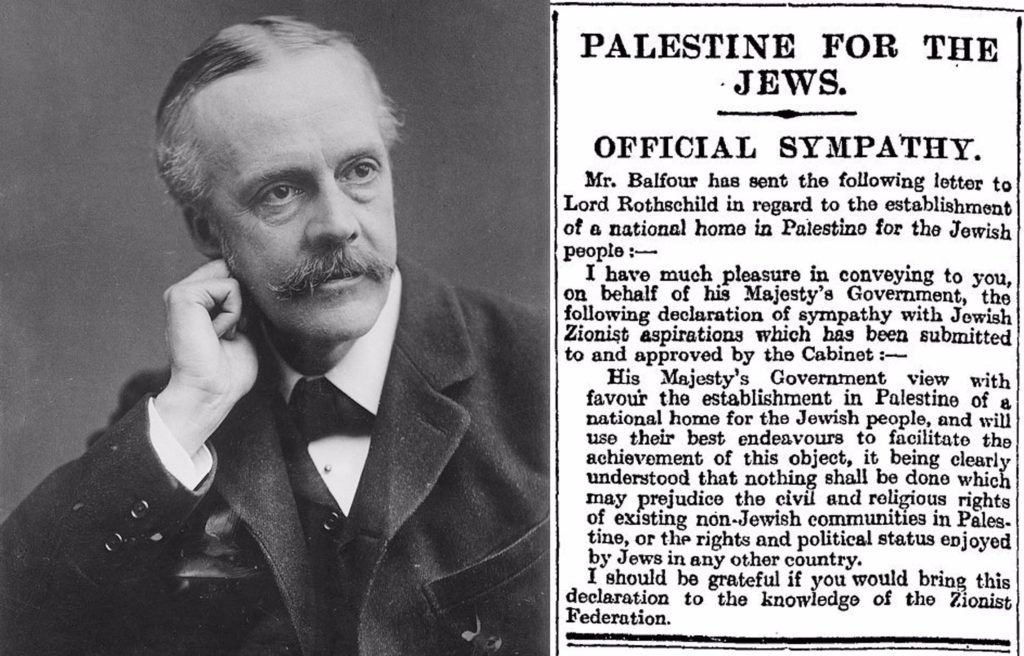

Last week marked the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, the famous letter in which the British government declared that “it viewed with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”.

It was a key part of the chain of events which led to the Jewish people finally realising self-determination in their ancestral homeland – what is now the thriving, democratic and innovative nation of Israel.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misunderstanding about the declaration and the context in which it was issued.

At the more extreme end, anti-Israel critics hold that Britain had no right “to promise territory that wasn’t hers”, and if only the Balfour Declaration had not been issued, the current situation the Palestinians find themselves in would never have happened. Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas, who is 12 years into his four-year term, last year threatened to sue the United Kingdom over it, while just this week, PA Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah tweeted: “Britain should apologise for the historic injustice it committed against Palestinians and correct it instead of celebrating it.”

Correct what, exactly? The PA claims it is committed to a two-state outcome and has recognised Israel’s right to exist, ie that it has accepted “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”. A “correction” to the Balfour Declaration would mean denying Israel’s right to exist. Frankly, the hypocrisy of this position lays bare the PA’s problematic approach to peace with Israel.

Still problematic are commentators such as Gwynne Dyer who in this publication on Oct 28 painted the declaration as the act of a single nation which set off a “hundred year struggle for Palestine”, which omits both the context of the declaration itself and the history of the years between it and the birth of the new state.

While on the face of it, the declaration may appear to be the act of a single nation, a recent essay in by Middle East historian Prof. Martin Kramer reveals that the British government was far from acting alone. Rather, the declaration was a reflection of consensus that had been reached between the allied nations of World War I. Indeed, Mr. Kramer writes, the process of consensus-building “might even be seen as roughly comparable to a UN Security Council resolution today”.

The British government was sympathetic to the Zionist cause but reticent to act without the blessing of the allies. So the Balfour declaration was not issued until statements sympathetic to Zionist goals of a Jewish homeland in Palestine were issued by France, the US and the Vatican. Also signing on were some major Arab leaders, and ultimately, the Ottoman Empire itself.

This allied consensus was given more concrete form at the San Remo Conference of 1920, and the Balfour Declaration entered the text of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine in full, becoming binding international law.

Furthermore, to be clear it was not only the origins of the Jewish state that were being put in place after the war. The victorious allies also laid the foundations for numerous new Arab states to arise out of the ashes of the Ottoman Empire, among them Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Yemen.

But San Remo and the British Mandate still didn’t guarantee Israel’s establishment – as we know, it took another 28 years for the dream of a Jewish homeland to be realised. Britain would cool its enthusiasm for the project, granting all the territory east of the Jordan River to the Hashemite kingdom of Transjordan in 1921 (now Jordan).

A British government White Paper in 1922 limited Jewish immigration in the territory remaining, but this did not stop the Arabs from their Revolt of 1936-39 which resulted in the British backing down further and issuing the 1939 White Paper on the eve of the Holocaust, which severely limited Jewish immigration at the exact time when millions needed to escape Europe.

The internationally endorsed Partition Plan of 1947 then resolved to divide what remained of the Mandate into two states – one for Jews and one for Arabs. History records that the Zionists accepted this plan, while the Arabs rejected it out of hand and started a war aimed at the new Jewish state’s annihilation.

This was the actual point at which the current Palestinian plight was created – if that rejection had not occurred, there would now be a Palestinian state as longstanding as Israel. Moreover, neither the Palestinian refugees of the 1948 war nor the similar number of Jewish refugees would have lost their homes.

The Palestinians have since rejected peace offers in 2000, 2001 and 2008 that would have given them their own state, abandoned negotiations in 2014, and continue on a path of attempting to demonise Israel rather than coming to the negotiating table. Yet they insist the Balfour Declaration is to blame for their current woes.

The Balfour Declaration gave the Zionist movement momentum at a crucial time, but the path to where things stand today was influenced by many different actors – including primarily the Arab world and the Palestinians themselves – all of whom should rightly accept their own share of responsibility for what has transpired since.

Gareth Narunsky is a Policy Analyst at the Australia/Israel & Jewish Affairs Council, a premier public affairs organisation for the Australian Jewish community.

Tags: Israel