Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Ankara Away

Oct 27, 2020 | Oved Lobel

Assessing the Turkish challenge to Israel

“Iranian power is fragile, but the real threat is from Turkey,” Mossad chief Yossi Cohen reportedly told the spy chiefs of Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE a couple of years ago.

Israel’s military intelligence allegedly classified Turkey as a “challenge” to Israeli interests for the first time in 2020, tying this challenge directly to the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his support for political Islamists like the Muslim Brotherhood.

Israel’s Defence Minister Benny Gantz, in a recent Zoom briefing organised by the Arab Council for Regional Integration following the Israeli normalisation with the UAE and Bahrain, accused Turkey of promoting instability, declaring that “we must take all the options that we have in our hands and try to influence [Turkey] through international pressure to make sure that they are pulling their hands [away] from direct terrorism.”

While Erdogan is extremely hostile to Israel – though perhaps not as hostile as Turkey’s secular opposition, which accuses Erdogan of being too soft and all talk – Turkey is not currently a comparable threat to Iran.

Turkey does not have a revolutionary ideology centred on the destruction of Israel; it does not stockpile explosives throughout the world or proliferate sophisticated weaponry and missiles to proxies for the sole purpose of threatening Israel; and it retains, despite the rhetoric and multiple strategic differences, a healthy trade relationship with Israel, although official diplomatic ties have been on ice since 2018. Furthermore, despite the vitriol, Turkey’s official position is still to support a two-state resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The challenge of Turkey is that of an aggressive rising power disrupting the status quo in its perceived favour. As its military power has grown, particularly its mastery of drone warfare since 2018, so too have its aggressive attempts to rewrite the regional order and circumvent international law, which it views as constraining its interests and ambitions, using hard power.

All of this is taking place in a strategic vacuum as the US increasingly disengages from the region.

Chief among Turkey’s goals in this regard is the pursuit of a regional condominium with Russia – and to a lesser extent Iran – and the reduction of US and Western presence and influence. While Turkey and Russia are strategic competitors, both view the US as the main hindrance to their interests and wish to bilaterally horse-trade spheres of influence in their multiple conflicts.

This trend certainly presents overlapping but generally distinct challenges to Israel’s interests, which include a US-backed regional order. Although Turkey seeks to assert itself in multiple areas, Israel should be able to compartmentalise these challenges and deal with them individually while maintaining some sort of relationship, however dysfunctional, with Turkey.

Turkey, Hamas and the Palestinians

Erdogan’s hostility towards Israel is no surprise. His AKP party is the political offspring of Turkey’s older Islamist Welfare Party, whose political platform pinned all of Turkey’s problems on “world imperialism and Zionism, as well as Israel and a handful of champagne-drinking collaborators in the holding companies that feed it.”

There is little doubt Erdogan was looking for an excuse to destroy Turkey’s previous strategic relationship with Israel, and he found it in Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s first major offensive against Hamas rocket attacks and attack tunnels in Gaza in 2008-9. Erdogan used the opportunity to block Israeli participation in NATO exercise “Anatolian Eagle,” leading to its cancellation. He then organised the infamous Gaza Freedom Flotilla in 2010, a direct provocation meant to resonate politically at home and justify his attempts to downgrade the relationship.

Erdogan’s sympathy with and support for Hamas is also no surprise, as his own roots, like Hamas’, are very much in the Muslim Brotherhood movement. He has always supported the group, and embraced Hamas’ electoral victory in 2006. This support escalated substantially as part of the 2010 provocation, with Turkey beginning to host senior Hamas leaders around 2010-2011 and even allegedly funding their terrorist operations directly. In 2018, Israel’s Shin Bet security agency revealed that Hamas’ military activities were being funded and run out of an office in Istanbul overseen by Hamas’ military commander of terrorist activities in the West Bank, Saleh al-Arouri.

As part of the investigation, the Shin Bet fingered Zaher Jabarin as the terrorist recruiter and arrested Daram Jabarin as a financier. In 2019, the US sanctioned Turkey-based Zaher Jabarin, the head of Hamas’ Finance Office, for using several companies in Turkey to raise funds for Hamas activities. The US asserts that Jabarin and his companies in Turkey are also Hamas’ primary points of contact for Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the group’s primary backer.

More concerning is the Shin Bet’s allegation that Turkey provides direct military assistance to Hamas via SADAT, an ostensibly private Turkish security company that seeks “Defensive Collaboration and Defensive Industrial Cooperation among Islamic Countries to help the Islamic World.”

Further revelations about the group’s Turkey operations came from Suheib Yousef, a son of Hamas co-founder Sheikh Hassan Yousef, who left the group. Yousef alleges that Hamas also runs signals intelligence stations in Turkey using “advanced equipment and computer programs” to spy on Israel, the Palestinian Authority and Arab States, and then sells that information to the IRGC in exchange for financial aid.

During a May 2019 flareup in Gaza, Israel bombed a building it claimed was being used as a command centre by Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, a building that not coincidentally housed Turkey’s state-run news agency Anadolu. In August this year, Israel revealed that Turkey had given passports to about a dozen senior Hamas operatives based in Istanbul. Meanwhile, Turkey has joined Russia in its attempts to unify the major Palestinian groups, Fatah and Hamas, in the wake of Israel’s normalisation with Bahrain and the UAE.

Turkey’s soft power push in Jerusalem is also of concern to Israel, especially efforts by the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA). This agency reportedly bankrolls a substantial portion of civil society activity in east Jerusalem, gives cash and food handouts to Palestinians in the city and allegedly collaborates with the controversial Turkish Islamist charity IHH.

Another Turkish aid organisation, the International Kanadil Institute for Humanitarian Aid and Development, was banned in Israel in late 2016 for allegedly funding Hamas and Muslim Brotherhood-linked projects in Jerusalem. There are reports that Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs formulated a specific program in 2019 to counter Turkish influence in Jerusalem.

Turkey’s expansive soft power role in east Jerusalem is all the more concerning given Erdogan’s statement to party colleagues on Oct. 1 that “Jerusalem is our city.”

Turkey, Iran and Hezbollah

Long before the rise of the political Islamists, Turkey had an ambivalent relationship with the revolutionary theocracy in Iran, refusing to support US sanctions since 1979. Prioritising relations with the Muslim Middle East has been an enduring idea in Turkey since the 1970s, an idea that Erdogan’s mentor Necmettin Erbakan, leader of the Islamic Welfare Party, attempted to implement during his abortive year as Prime Minister. Erbakan proclaimed that Turkey “will set up an Islamic United Nations, an Islamic NATO and an Islamic version of the European Union.” The lynchpin of this plan was establishing closer relations with Iran, Turkey’s “Muslim Brother” and paragon of “resistance” to the West. Erbakan flew to Iran to sign a US$23 billion gas deal in direct defiance of US efforts.

Erdogan has picked up where Erbakan left off, massively expanding trade with Iran after the rise to power of his AKP party in 2002 and attempting another gas deal in 2007. Erdogan viewed his role as protecting Iran’s nuclear program from sanctions, and he has consistently tried to deepen economic ties with Teheran. Moreover, once sanctions were imposed, the Turkish government allegedly oversaw the “gas-for-gold” scheme and other activities to help Iran circumvent US pressure. About radical Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Erdogan said “There is no doubt he is our friend,” and he went out of his way to amplify Iranian propaganda regarding its nuclear program.

A recent report alleges that the director of Turkey’s English-language State Broadcaster TRT World, Fatih Er, is being investigated by Turkey’s judiciary for his role in the IRGC’s network in Turkey, as was the current Minister of Industry and Technology Mustafa Varank and Erdogan advisor Sefer Turan.

Erdogan has not only financially facilitated Iranian expansion, but has also allowed the IRGC and its proxies free rein when it comes to Israel. Erdogan and his intelligence chief Hakan Fidan allegedly began passing on intelligence from the US and Israel to Iran and even reportedly blew the cover of an Israeli spy network inside Iran.

He has also allegedly helped Hezbollah, Iran’s Lebanese proxy, transport weapons and missiles into Lebanon. According to reports, this began during the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel and continued at least through 2009 despite multiple Israeli diplomatic protests. After a meeting with Hezbollah’s Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah in 2010, Erdogan reportedly defended Hezbollah over accusations that it had killed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri and dozens of others in 2005, proclaiming “Hezbollah says it’s the spirit of resistance in Lebanon and even uses the expression ‘Hariri’s shahid.’ [martyr] No one can suspect it of being involved in this.” In fact, the UN-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon legally implicated Hezbollah in Hariri’s murder in August 2020.

Turkey does have many strategic differences with Iran, most notably its attempts to topple the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, the fulcrum of Iran’s “axis of resistance” against Israel. Turkey also supported the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen against Iran’s local proxy Ansar Allah, also known as the Houthis, offering logistical support and declaring that “Iran and the terrorist groups must withdraw.”

However, as it does with Russia, Turkey would much prefer to divide the region with Iran and manage the conflicts bilaterally and occasionally trilaterally with Russian participation. Erdogan and the AKP have an ideological sympathy for a fellow Muslim state under pressure from the US.

At the 6th Turkey-Iran High-Level Cooperation Council meeting in September, co-chaired by Erdogan and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, the two leaders agreed to continue developing the economic relationship and to cooperate in the fight against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Turkey and Political Islam

The events of the so-called Arab Spring in 2011 produced two diametrically opposed regional blocs. On the one hand, Turkey and Qatar threw their weight behind the Muslim Brotherhood, which for a brief moment seemed politically ascendant across the region, especially after the Brotherhood gained control of Egypt under President Mohamed Morsi in 2012-13. On the other side, the UAE and Saudi Arabia reacted with horror at US disengagement, encouragement of the Brotherhood and the collapse of autocratic allies and client states like Egypt. Thus began a Cold War across the Middle East and Africa, as a conservative alliance led by the UAE sought to reimpose or prop up military dictatorships in Libya, Sudan, Egypt, Yemen and elsewhere and re-establish the status quo ante, while Turkey and Qatar promoted Islamist groups, often under the guise of at least superficial political pluralism.

Like his mentor Erbakan, Erdogan is very intent on setting up an Islamic order with Turkey as a key leader. Certain initiatives, such as the Islamist Kuala Lumpur Summit in Malaysia in 2019, are intended to supplant the Saudi-led Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), and Turkey has even seemingly succeeded in poaching Pakistan, an erstwhile Saudi client state, from Saudi Arabia by involving itself rhetorically in the Kashmir conflict and defending Pakistan from blacklisting by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) for terrorism funding.

In the Middle East, Turkey has become the primary bastion and safe haven for the Muslim Brotherhood, which has been thoroughly crushed as a political force in Egypt and across the region. Jordan, aligned with the UAE camp, dissolved the local Brotherhood branch in July, while the UAE, like Saudi Arabia, declared it a terrorist organisation in 2014.

In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood has allegedly spawned terrorist offshoots, like the Hasm movement, which Egypt claims is controlled by senior Muslim Brotherhood figures in Turkey. Like Qatar, Turkey has become a base for Muslim Brotherhood-aligned broadcasts into countries like Egypt.

While none of this is directly threatening to Israel, the stability of its Arab allies is obviously of tremendous concern. Moreover, the 2017 Arab blockade of Qatar, directly related to the latter’s support for the Muslim Brotherhood, undermined the ostensible united front against Iran and exacerbated the already tense relations of most Arab states with Turkey.

This Cold War also directly impacts Israel’s attempts to win official diplomatic recognition from other Muslim states aside from the UAE and Bahrain – which may only be possible if UAE-aligned factions in places like Libya and Sudan are victorious over their Turkish-backed political and military opponents.

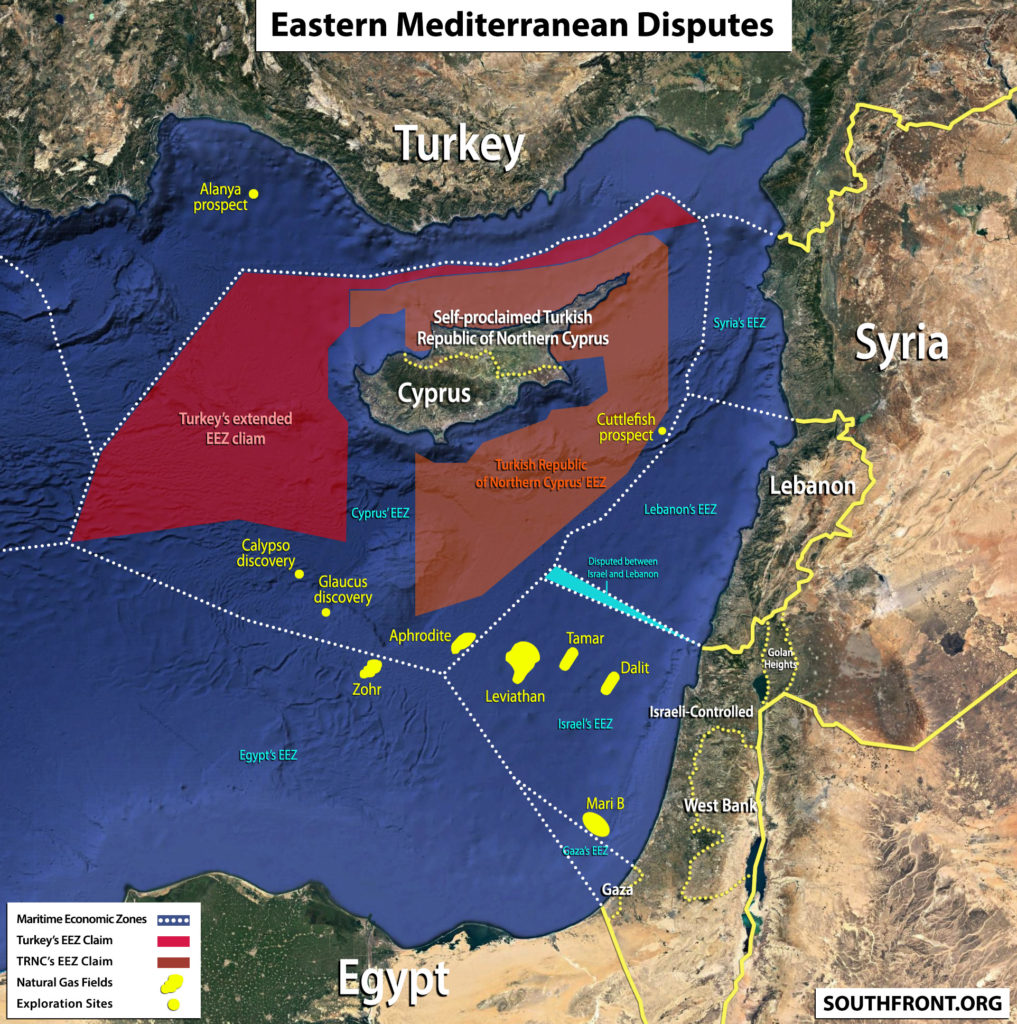

Turkey has been aggressively trying to enforce expansive Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) for both itself and the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” in the Mediterranean, including by drilling in internationally-recognised Cypriot waters

Turkey, Libya and the eastern Mediterranean

There are several interconnected issues, each aggravating the other, that make up the conflict in the eastern Mediterranean between Turkey on the one hand and almost every other country there on the other.

Foremost among these is the issue of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), especially those of a myriad tiny Greek Islands off Turkey’s coast, which have essentially confined Turkey’s maritime zone to a small corner of the Mediterranean Sea. This is why Turkey has refused to sign up to the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which it is trying to circumvent, arguing islands cannot generate EEZs.

The second related problem revolves around the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), an internationally unrecognised entity Turkey established in the 1970s during a conflict with the then Greek junta over Cyprus. The island is still divided today despite decades of talks on reunification. Turkey has used its occupation to challenge Cyprus’ EEZ by claiming one for the TRNC, while seeking to undermine more broadly Cyprus’ claims to recently-discovered gas reserves and its cooperation with Greece, Israel, Egypt and others in the East Mediterranean Gas Forum (EMGF).

These gas discoveries have given impetus to an already-coalescing alliance between Israel, Egypt, Cyprus and Greece – encouraged by the US – that Turkey views as an attempt to cut it out of regional gas supply and contain it, particularly via the proposed EastMed pipeline that would bypass Turkey and carry gas to Europe.

Israel is still reportedly involved in talks with Turkey over gas, as it has been since 2017. Moreover, the viability of the EastMed Pipeline is questionable and remains theoretical for the time being. Turkey continues to carry out provocative drilling in Cyprus’ EEZ, but there are no proven gas reserves in the area where it’s drilling. The conflict, then, is less about gas per se and more about Turkey demonstrating it won’t be excluded or contained.

Israel has also been increasing its trilateral military alliance with Cyprus and Greece, and the UAE, which has been partaking in exercises in Greece alongside Israel for several years, hosted a summit for Cyprus and Greece in late 2019. The US has also been increasing its military presence and deepening its alliance with Greece and Cyprus, even partially lifting the 1970s arms embargo on the latter as it reimposed an unofficial arms embargo on Turkey. A separate anti-Turkey alliance involving Egypt, the UAE, Greece, Cyprus and France was announced in 2020.

In Libya, Turkey and its proxy, the “Government of National Accord (GNA),” are locked in a temporarily-paused war with warlord Khalifa Haftar and his “Libyan National Army,” which has been attempting to take full control of the country for several years with the backing of the UAE, Egypt, Russia, France and others. As part of Turkey’s intervention to halt Haftar’s advance, it signed a farcical deal with the GNA delineating maritime borders that essentially gave Turkey full control of the eastern Mediterranean. This was obviously rejected by the international community and was followed by an equally far-fetched deal between Greece and Egypt on EEZs.

It is still unclear whether these activities are simply an opening gambit by Turkey intended to be bargained down during talks or whether Ankara actually intends to maintain these claims. With Turkey’s growing military power, however, the provocations in the eastern Mediterranean against Greece and Cyprus are likely to become far worse and will inevitably involve Israel.

Turkey, Syria, Iraq and the Kurds

Turkey’s extensive occupation of areas of Iraq and Syria is often portrayed as part of an expansionist “neo-Ottoman” imperial policy, but it is in fact largely a function of its on-and-off war with the PKK and the massive refugee influxes from Syria since 2011 due to the depopulation campaigns by the Assad regime and its supporters.

Turkey initially had a very proactive policy in Syria to overthrow the Assad regime by backing primarily Islamist rebel groups and encouraging a Muslim Brotherhood-dominated opposition movement. The rise of the PKK in Syria, encouraged by the Assad regime and then supercharged by the alliance of its Syrian branch, the PYD, with the US against the Islamic State, appears to have changed Turkey’s priorities. 2015 saw a PKK attempt to take over areas of Turkey. Since then, Turkey has focused primarily on limited invasions of territory controlled by PKK-affiliated groups to clear militants from its borders and forcibly return some of the approximately 4 million refugees it hosts.

In Iraq, Turkey has an extensive network of bases and tens of thousands of troops hunting the PKK in its primary base in Qandil and the north of the country, using its new-found drone capabilities to aggressively pursue the group.

Israel’s current relationship with the PKK and associated groups is unclear, although Israel is allegedly providing mainly humanitarian aid to Syrian Kurdish groups linked to the PKK. According to then-Deputy Foreign Affairs Minister Tzipi Hotovely, Israel has also forcefully advocated on behalf of the Syrian Kurds to the US. “The possible collapse of the Kurdish hold in north Syria is a negative and dangerous scenario as far as Israel is concerned,” she said.

Israel was the only country to have publicly supported an independent Kurdish State in Iraq following a referendum there in 2017, a position which infuriated Erdogan and led him to accuse the Mossad of being involved in the independence referendum there. Israel’s natural and historical sympathy for Kurdish independence is unlikely to change regardless of the relationship with Turkey.

The Curious Case of Azerbaijan and Armenia

Israel and Turkey are both allies of Azerbaijan, and when the historical dispute over the Nagorno-Karabakh region flared into all-out conflict with Armenia recently, sophisticated Israeli drones that had been sold to Azerbaijan were front and centre. Israel is Azerbaijan’s largest arms supplier, and an “air train” has reportedly been established over the past few weeks for Azerbaijani Ministry of Defence cargo planes to fly to Israeli military bases.

Armenia, on the other hand, has had a historically close relationship with Iran, which has allegedly been shipping it arms. Iran is officially neutral in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and, like Russia, has presented itself as a mediator rather than participant. Officially, Iran, like Russia, recognises Nagorno-Karabakh as Azerbaijani territory.

On the other hand, some of the most serious IRGC and Hezbollah terrorist plots have been directed at Israeli assets and individuals in Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan has helped foil these, severely straining its relations with Iran. Furthermore, Iran’s penetration of Armenia’s economy is extensive, and Armenia has reportedly supplied weapons to the IRGC. The US even sanctioned Armenia-based companies for facilitating Mahan Air, a private Iranian airline which allegedly acts as the IRGC’s transport and logistics service.

It is Turkey that has apparently driven the most recent escalation, dispatching its Syrian mercenaries and drones to assist Azerbaijan. While there may be tacit coordination between Israel and Turkey in support of Azerbaijan, it is far more likely that Turkey is trying to edge out Israel. Azerbaijan is a crucial oil supplier for Israel, and became Turkey’s most important gas supplier in 2020, and Turkey may believe it can outbid Israel’s influence and use gas and oil supplies as a pressure point.

Ultimately, Turkey’s likely goal is to supplant the international group responsible for mediating the Armenia/Azerbaijan conflict since the 1990s, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group – co-chaired by the US, France, and Russia. It would like to replace it with a trilateral arrangement with Russia and Iran, similar to the “Astana” partnership between the three countries in Syria.

Conclusion

Turkey is likely to become more aggressive as it becomes more powerful, and its hostility to Israel will remain a feature of its politics for the foreseeable future. In spite of this, outright Israeli conflict with Turkey is unlikely, and even Erdogan has shown cynical pragmatism in his relations with Israel and compartmentalised various elements of the relationship, such as trade and tourism. Yet judging from recent events, the more powerful Turkey becomes, the more this pragmatism will recede. Where necessary, Israel is capable of pushing back, directly or indirectly, and drawing its own red lines for Turkey’s brinkmanship across the region.

In terms of conventional military power, Turkey is much stronger than Iran, and could represent an existential challenge to Israel if it had the same genocidal, revolutionary intent that drives Iran. Thankfully, Erdogan’s actions to date do not match his venomous rhetoric. The challenge Turkey presents to Israel is that of a rising power ruled by an erratic dictator seeking to overturn a regional order of which Israel is a key element, not a revolutionary power like Iran which has made destroying Israel a key element of its raison d’etre. As both Turkey and Israel have demonstrated, regardless of the rhetoric and ideological conflict, it should still be possible to maintain some sort of relationship and avoid direct clashes.

Tags: Iran, Libya, Palestinians, Syria, Turkey