Australia/Israel Review

US Conspiracy network comes down under

Oct 1, 2020 | Naomi Levin

You could be forgiven for thinking the recent anti-lockdown protests in Australia were organised and attended by a tiny group of disparate individuals – mostly cranks – who brazenly ignore official health advice.

In part, you would be right. But you might not be aware that those instrumental in leading Melbourne’s demonstrations are, in some cases, tied up with the US-based conspiracy movement QAnon, as a dive into the darker recesses of social media has shown.

QAnon is an online movement that surfaced in the United States in 2017, but has since infiltrated other countries, including Australia. It is based on cryptic messages distributed by an anonymous source who is apparently a senior US official – known as Q – on the fringe social media platform 8kun (previously known as 8chan). It is ostensibly a far-right movement, but attracts anti-establishment types on the far-left as well. It also has a strong vein of antisemitism.

QAnon followers are united by a scepticism of the “deep state”, which they see as a corrupt cabal of global elites who run the world. Those “elites”, according to QAnon followers, include Microsoft founder Bill Gates; financier and philanthropist George Soros; and Hollywood celebrities ranging from disgraced, now deceased, producer Jeffrey Epstein to talk show host Ellen Degeneres. In addition to the allegations about having undue control over world affairs, QAnon followers also accuse many of the same people of involvement in a global paedophilia ring. According to QAnon, US President Donald Trump will bring this global elitist cabal to justice.

While this is the central theme of QAnon, there are thousands of threads tying it to other conspiracy theories, from opposition to immunisation, to convoluted ideas about the “real reasons” behind coronavirus lockdown measures – or the “plandemic”, as QAnon followers call it.

It is the pandemic that has really boosted the popularity of QAnon in Australia. Australians who are unhappy with lockdown measures are using social media to discuss and debate the “clues” dropped by Q in an attempt to discover the “truth”.

QAnon is not a membership movement so it is impossible to know how many followers it has. While it is predominantly US-based, Canadian academic Marc-Andre Argentino has estimated Australia is in the top five countries for QAnon activity. But how has QAnon – a conspiracy theory movement so embedded in American politics – gained traction in Australia?

Researcher Dr. Kaz Ross from the University of Tasmania has found that One Nation politicians have raised conspiracy theories that may have led Australians down the QAnon “rabbit hole” – the common term used to describe those who start believing QAnon-spread nonsense. AIJAC is not suggesting that the One Nations senators are themselves involved in or supporters of QAnon.

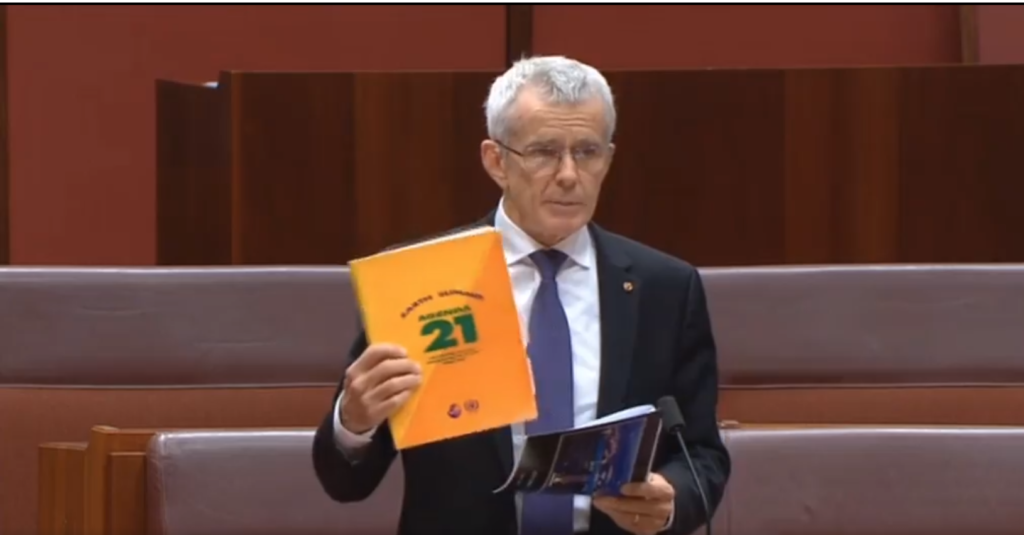

Dr Ross, a humanities lecturer, has pointed to One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts’ repeated support in Parliament for the baseless Agenda 21 conspiracy theory, starting from his Sept. 2016 first speech, as one factor that has pushed his Australian supporters down the QAnon rabbit hole.

Agenda 21 was a non-binding sustainability plan adopted by UN members in 1992, but Dr. Ross explains that: “The belief that ‘Agenda 21’ is a blueprint for corrupt global governance has become a core tenet of QAnon in Australia.”

One Nation leader Pauline Hanson, in attempting to move an “All Lives Matter” motion in the Senate earlier this year, also may have succeeded in dragging Australians into the QAnon net, according to Dr Ross.

The “All Lives Matter” slogan – used in opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement – has been co-opted by far-right movements as a rallying cry and mantra of racists.

“It sickened me to see people holding up signs saying ‘Black Lives Matter’ in memory of this American criminal [George Floyd]. I’m sorry but all lives matter,” Senator Hanson told the Senate in June. She went on to proclaim that more white people die in police custody in Australia than black people, while neglecting to mention that only 3.3% of Australia’s population is Aboriginal, and that the Aboriginal population is significantly over-represented in deaths in custody figures.

Deakin University academics Joshua Roose and Lydia Khalil agree that anger over restrictions put in place in response to the coronavirus has driven some Australians towards extremist movements. They write that “the pandemic has also given rise a prolonged period of collective stress and trauma which has made more people susceptible to disinformation, conspiracies, and extremist narratives.”

Public trust in traditional institutions – like government, organised religion and mainstream media – was already low before the pandemic, and this created space for alternate messages to be amplified, they noted.

ASIO, Australia’s internal intelligence agency, also says that far-right extremist movements have blossomed locally during the pandemic.

“COVID-19 restrictions are being exploited by extreme right-wing narratives that paint the state as oppressive, and globalisation and democracy as flawed and failing,” a media statement from ASIO said.

“We assess the COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced an extreme right-wing belief in the inevitability of societal collapse and a ‘race war’.”

The ASIO statement explained that the risk of violence associated with Islamist terrorism remains a bigger threat in Australia, but said that “extreme right-wing groups and individuals represent a serious, increasing and evolving threat to [Australia’s] security.”

One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts bringing up the “Agenda 21” conspiracy theory in his first speech in 2016

The ideas raised by the One Nation senators – Agenda 21 and All Lives Matter – are not only fringe, but they both have racist links or connotations. In the case of Agenda 21, explicit antisemitism has often been a key part of those connotations.

There has been much research done on the links between coronavirus conspiracy theories and antisemitism.

As Dr Ross wrote of Senator Roberts’ Agenda 21 Senate speeches: “Any talk of ‘global bankers and cabals’ directly taps into longstanding antisemitic conspiracies about supposed Jewish world domination often centred on the figure of billionaire George Soros. The pandemic and QAnon have also proven to be fertile ground for neo-Nazis in Australia.”

Canadian researcher Argentino also observed a “fair amount of antisemitism” on Australian QAnon notice boards.

In the United States, antisemitic QAnon supporters have allegedly made online death threats against Jewish California State Senator Scott Wiener, a Democrat. In August, Wiener told media that at least a quarter of the social media hate mail he received was antisemitic in nature. He attributed much of this to QAnon supporters.

“It’s very disheartening that this is what the country has come to, that we have this cult, QAnon, that is gradually taking over the Republican Party,” he said.

The abuse has not come from Republican party figures, Wiener told JTA, but “their party is unfortunately being more and more influenced by QAnon.”

Marjorie Taylor Greene, a US House of Representatives candidate for the November election in the 14th district of Georgia, is the first Republican candidate to openly support QAnon. She has published videos calling Q “a patriot” and “something worth listening to and paying attention to.” US President Trump has spruiked Greene’s candidacy, calling her a future Republican star who is “strong on everything”.

American media reports suggest that other Republican candidates have expressed an openness to QAnon theories. However, there are also Republicans who have denounced QAnon, including former Florida governor Jeb Bush, the brother of former Republican president George W Bush, and Liz Cheney, high ranking Republican Representative for Wyoming and daughter of former Republican vice president Dick Cheney.

While the clues dropped by Q – the supposed messenger of the QAnon movement – do not espouse violence, the FBI has identified QAnon as “very likely” to “motivate some domestic extremists, wholly or in part, to commit criminal and sometimes violent activity.”

A 2019 FBI intelligence bulletin said: “The FBI further assesses in some cases these conspiracy theories very likely encourage the targeting of specific people, places and organisations, thereby increasing the likelihood of violence against these targets.”

A number of prominent US terrorism incidents have already been linked to extreme-right movements, QAnon included. Amongst the most well-known was the deadly shooting at the Chabad of Poway synagogue in California in 2018.

In Australia, there are currently no far-right groups on the Commonwealth Government’s terrorist list. Shadow Home Affairs Minister Senator Kristina Kenneally has called for a review of the criteria by which Australia proscribes terrorist groups, to allow the country to better sanction far-right groups.

“The Australian government and all federal parliamentarians must now take the terrorist threat of right-wing extremism seriously and respond,” Senator Kenneally said. “The Morrison government could begin this work by referring Australia’s terrorist listing criteria to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security for review.”

According to media reports, the Australian Government has not accepted Senator Kenneally’s request at this stage.

Another front from which to contain extremist movements like QAnon is social media. QAnon followers congregate on social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, but also less popular platforms.

In August, Facebook announced it had removed 790 groups and 100 pages from its platform, blocked 300 QAnon-related hashtags, and suspended more than 10,000 Instagram accounts. Twitter also suspended 150,000 QAnon-related accounts that violated the platform’s policies. This is just the tip of the iceberg though. AIJAC had no difficulty in finding QAnon material still available on all social media platforms.

So what can be done about QAnon’s encroachment into Australia? Given many researchers see much of QAnon’s local success as tied to the pandemic, as lockdowns ease and governments establish “COVID normal” practices in their communities, the natural attraction of QAnon and similar movements may diminish.

However, Roose and Khalil suggest that leaders, including religious leaders, need to speak out against the growth of belief in extremist narratives like that of QAnon: “If the acceleration of violent extremism is not addressed during these times of crisis, it will allow extremism and the distrust of government and mainstream religion to incubate and spread. This will make recovering and maintaining political legitimacy and trust in institutions in the long term all the more difficult.”

Tags: Antisemitism, Australia, Far Right, QAnon, United States