Australia/Israel Review

Essay: A Sad Legacy

Sep 1, 2022 | Eliana Chiovetta

Australia’s experience with Nazi war criminals

For most of the last 70 years, Australia had a long-standing public policy problem with regard to dealing with the hundreds, at least, of alleged Nazi war criminals who immigrated here following the Second World War. An environment of indifference, even tolerance, for these alleged Nazi war criminals was sustained for decades due to a number of factors, notably significant gaps in legal frameworks and ambivalence within government circles, and the context and tensions of the Cold War. Finally, starting in the late 1980s, efforts were belatedly made to prosecute and later extradite some alleged Nazi war criminals, but none of these efforts succeeded.

On Dec. 13, 2017, the legal element of this long saga came to an end with the death of 96-year-old Perth resident Charles Zentai, the last known alleged Nazi war criminal in Australia.

This article is an attempt to analyse the lasting imprints Australia’s poor record of identifying and failure to take successful legal action against Nazi war criminals has had on this country, both in terms of the many Australian communities impacted, and its legacy for Australia’s legal system.

Post-war immigration

Australia’s response to Nazi War criminals can be divided into three main periods: 1. the 1940s through 1980s (i.e. the period of indifference); 2. the late 1980s to 1990s (the period of prosecution attempts), and 3. the 2000s (the period of extradition attempts).

Australia joined the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) in the 1940s, alongside other allied nations, with the aim to “investigate and record the evidence of war crimes,” ultimately leading to the Nuremberg trials. International and national legal structures to pursue and punish Nazi war criminals were developed, with Australia’s participation in UNWCC focussed on Japan.

However, in 1947 then Australian Prime Minister Ben Chifley declared, with reference to the Japanese, that “the major tasks of UNWCC have been completed and the laws pertaining to war crimes adequately developed.” Chifley told Parliament that he “could not see purpose in continuing investigations aimed at tracing war criminals, which could go on for an extended period.” Australia did, however, ratify the UN Genocide Convention in 1949.

Many of the alleged former Nazi war criminals who settled in Australia immigrated from the former Baltic states (especially Lithuania) and eastern Europe (i.e. Belarus, Poland, and Czechoslovakia). Australia was one of four nations which had mass post-war-immigration programs for displaced persons from war-ravaged Europe, the other three being the US, Canada and Israel. All of these states, apart from Israel, later had issues with Nazi war criminals being identified, although a very small percentage of those immigrants.

Meanwhile, Jews have historically been a significant part of Australia culturally, politically and socially. In 1933, Australia’s Jewish population was approximately 23,000. Between 1933 and 1938, 8,000 Jewish refugees immigrated to Australia, with an additional 5,000 in 1939. By 1961, the Jewish population increased by almost two and a half times, reaching 60,000, thanks to post-war immigration, mainly of Holocaust survivors.

Australia’s Jewish community came to have the second largest per capita number of Holocaust survivors – second only to that of newly formed Israel. In total, Australia came to be the home of approximately 31,000 Holocaust survivors.

The discovery of former Nazi war criminals living in Australia had, unsurprisingly, significant effects on Holocaust survivors in Australia. These discoveries both enraged many survivors, and arguably helped create an increased impetus for Holocaust education and preserving the Holocaust remembrances of Australian survivors.

The lack of effective laws and the presence of alleged Nazi war criminals within Australia was very occasionally raised in mainstream public debates in subsequent years, but it was not fully addressed and acknowledged until the 1980s.

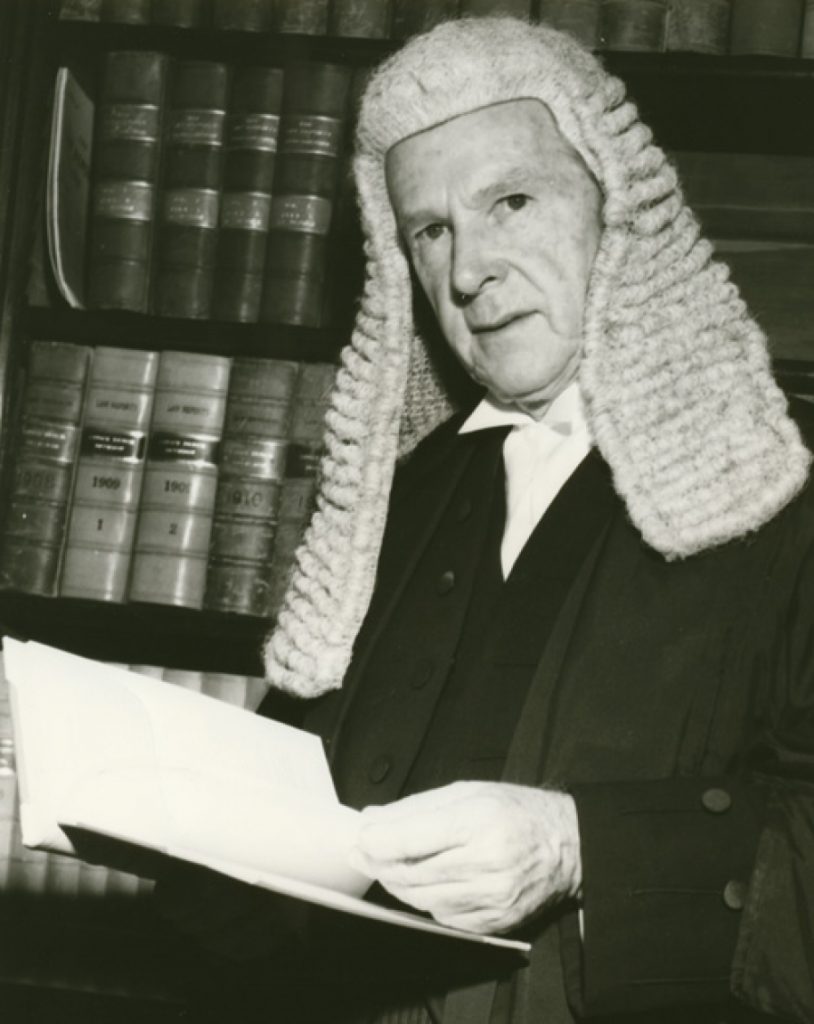

Sir Garfield Barwick, who argued war criminals who came to Australia should be allowed to “turn their back on past bitterness… and make a new life”

A key background reason for this was the Cold War, where Australian foreign policy was focussed heavily on anti-Communism, and where the push to prosecute war criminals from eastern Europe was often seen as a dubious initiative, based on suspect evidence, originating from totalitarian communist regimes.

Thus, in 1961 Australian Attorney-General Garfield Barwick turned down a Soviet request for extradition of alleged war criminal Ervin Viks. Barwick said that it was “the right of this nation, by receiving people into this country, to enable men to turn their backs on past bitternesses and to make a new life for themselves and for their families in a happier community.”

By the 1970s, the Australian Jewish community, as well as others in Australian society, had become vocal in calling attention to the alleged war criminals. The late 1980s to early 1990s marked a transition period, when significant progress began to be made towards seeking to address and take action on the issue of Nazi war criminals within Australia.

Steps towards prosecution in Australia – the Hawke Government

The Hawke Government was the first to officially acknowledge Australia’s apparent unofficial “safe haven” status for war criminals, leading to the Menzies review of 1986, in which the Government appointed A.C. Menzies AM OBE to oversee a review of material related to the entry of suspected war criminals into Australia. Menzies concluded that it was likely that a significant number of people who had committed war crimes had entered Australia and that action needed to be taken.

Two key events had sparked the Australian Government changing its approach to war criminals at this time. One was public controversy over the arrest in the US in 1985 of a long-term US resident with Australian citizenship named Konrad Kalejs on war crimes charges. The US Department of Justice alleged that, between July 1941 and June or July 1944, Kalejs was a company commander in the notorious Arajs Kommando, a local police unit which assisted the Einsatzgruppen death squads to murder Jews and Roma in Latvia. After several years of court battles, Kalejs was eventually deported back to Australia.

Konrad Kalejs, the Australian citizen whose arrest in the US on war crimes charges in 1985 sparked a debate about Australia’s legal responses (Image: AAP)

The other event was the broadcast of the pioneering radio documentary series “Nazis in Australia”, produced by investigative journalist Mark Aarons, on ABC Radio National in 1986, demonstrating Kalejs was only one of many Nazi war crimes cases.

The Hawke Government subsequently introduced the War Criminal Amendments Act, which passed the House of Representatives in October 1987 and finally passed the Senate in December 1988.

The 1988 Act amended the War Criminals Act of 1945, allowing Australian Military Tribunals to try Japanese defendants for the alleged commission of atrocities in World War II, to also allow the prosecution of any Australian citizen or resident who committed war crimes between “on or after 1 September 1939 and on or before 8 May 1945.” Section 21 of the amended act required the attorney-general to report annually on operations to carry out such prosecutions.

The plan to introduce the War Crimes Act in the 1980s sparked intense public debate, including strong opposition from some sources. Justice Michael Kirby, then President of the New South Wales Court of Appeal, argued that Australia could not prosecute Nazi war criminals after such an extended period of time if “fairness and respect for human rights” were to be upheld within Australian courts. The President of the Bar Association, Ken Handley QC, asserted that the War Crimes Act was merely “an expensive propaganda excuse” and the Law Council of Australia argued a fair trial was unlikely due to the lack of availability and lack of reliability of key evidence.

David Pennington, Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne, urged forgiveness instead of “vengeance for crimes long after they were committed,” raising concerns about traditional Christian anti-Jewish discourse being deployed in these debates over war crimes.

The SIU

Based on a Menzies Review recommendation, the Hawke Government also established the Special Investigations Unit (SIU) in May 1987, tasked with collecting evidence on the commission of war crimes.

The primary role of the SIU was to investigate all allegations of Nazi war criminals living in Australia. Allegations ranged from leading death squads to serving as SS guards – 841 people were investigated in all. Victoria had the most cases of any state, with New South Wales a close second. Eight hundred and nineteen of the cases were suspended for a variety of reasons, including unsubstantiated or insufficient evidence, the defendant being deceased or in poor health and, in some cases, investigators concluding the allegations of war crimes were simply false. Twenty cases remained open when the SIU was shut down in late 1992 for the following reasons: four cases were referred to the DPP for prosecution, four cases were amalgamated with earlier files, and 14 allegations were made on June 10, 1992, only 20 days before the SIU was shut down (leaving the investigations incomplete and still open).

Despite funding increases through its last year of operation, suggesting the importance and growing viability of the organisation, the SIU was controversially shut down by the Keating Government, which argued it had accomplished its goal and was no longer necessary.

The SIU remained in operation until June 30, 1992, when it was replaced with the War Criminal Prosecution Support Unit (WCPSU), tasked with prosecuting defendants based on the SIU’s evidence. From its formation in July 1992 to its disbandment on Jan. 31, 1994, the WCPSU only launched three prosecutions, none of which resulted in a conviction.

The three cases that were prosecuted based on SIU evidence demonstrated many practical and evidentiary problems within Australian criminal law with respect to war crimes cases for crimes committed overseas; specifically, difficulties pertaining to obtaining reliable eyewitness accounts, testimony, and identification.

Ivan Polyukovich

The SIU’s most famous case was against Ivan Polyukovich, the only person to be tried under Australia’s amended War Crimes Act. In January 1990, Polyukovich was arrested in Adelaide for his alleged involvement in a mass execution of some 800 Jews from the Jewish ghetto in Serniki in occupied Ukraine when he served in the Forestry Department of the Nazi Wehrmacht, as well as personally killing others later during WWII. The case took over three years, with the formal trial beginning in March 1993. However, Polyukovich was found “not guilty” by a jury on May 18th, 1993. Despite corroborating eyewitness testimony, there were issues with some of the translations and some of the witnesses were too elderly to take the stand. As crusading journalist Mark Aarons explained, “Many of the witnesses had died, many were elderly, the defence lawyers were able to cast doubt on the veracity of their memories.”

The other two cases prosecuted by the SIU also failed, with charges against Mikolay Berezowsky dismissed at his committal hearing and the case against Heinrich Wagner dropped due to Wagner’s poor health after he suffered a heart attack. These cases re-emphasise the incredible importance of speedy trials and the serious difficulties created by long time lapses between the commission of war crimes and the prosecution of the perpetrators.

The fourth case recommended for prosecution by the SIU was later revealed to be against Karlis Ozols, [see below], but this case was never pursued due to the closure of the SIU by the Keating Government before investigations could be completed.

Efforts and progress post-SIU

After the SIU was closed, progress on addressing the legacy of Nazi war criminals in Australia largely dropped from the public radar for some time. Efforts revived again in the 2000s, especially regarding amending Australia’s extradition process to allow alleged perpetrators to face trial in the European countries in which their crimes were allegedly committed.

Previously, this had not been viewed as possible because most of the countries concerned were part of the Soviet Union or its satellites, and there was little confidence defendants could receive fair trials in those totalitarian countries. Attitudes were slowly shifting, as demonstrated by Justice Minister Senator Christopher Ellison, who commented in a media release “transnational crime requires transnational response.” Successive Australian governments therefore continued to strengthen their commitment to dealing with this issue, and improve the legal system’s capabilities throughout the 2000s, with repeated amendments to the Extradition and Mutual Assistance Arrangements Act of 1988.

However, no extradition effort led to an actual conviction in an Australia Nazi war crime case. In one prominent case, Konrad Kalejs was sought for extradition to Latvia in 2000. A Melbourne Magistrate found Kalejs should be extradited, but he died in late 2001 before the extradition process could be completed. In another case, Charles Zentai was ordered to be extradited to Hungary in 2009, but his extradition was overturned by the High Court in 2012.

The growth of Australia’s commitment to additional measures to seek justice concerning Nazi war criminals can be seen via revisions within the Simon Wiesenthal Centre’s (SWC) national ratings on dealing with Nazi war criminals. In the 1990s, Australia regularly received an “F” for “consistently failing to hold Holocaust perpetrators accountable” and “a weak will to proceed with prosecutions.” Australia was upgraded to a “D” and then to a “C” in the 2000s. The upward shift in grade can be attributed primarily to the proceedings to seek to extradite Charles Zentai. However, despite better efforts, the SWC still described Australia as “lacking in political will” with respect to seeking justice for alleged Nazi war criminals in Australia.

Australian War Crimes Law reforms

Legally, 2002 was a threshold year, establishing more solid foundations for Australia to continue the progress seen over the past two decades in learning from the impact of alleged Nazi war criminals’ immigration to Australia. This was due to the passage of new provisions for the prosecution of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes which came into operation under div 268 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) (‘Criminal Code’). However, these new measures also have not yet resulted in any successful prosecutions in Australia – though the extradition of Croation Serb militia leader Dragan Vasiljkovic in 2015 led to his conviction in Croatia.

After the SIU’s closure, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) became responsible for investigating potential war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide within its jurisdiction. But this jurisdiction prior to 2002 was very narrow, excluding war crimes committed in non-international armed conflicts (like the Rwandan genocide).

Up until 2002, such legal frameworks only pertained to first Japanese and then Nazi war criminals. These limitations excluded the ability to prosecute many other war criminals, resulting in Australia again being a potential “safe haven” for alleged war criminals, including, for example, former leaders in the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia, or perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide.

The Lowy Institute released a policy paper in 2009 which indicated that there were potentially hundreds of war criminals from former Yugoslavia, Cambodia, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and East Timor in Australia. The paper further emphasised the importance of prosecution in a timely fashion. Additionally, this policy paper, written by John Stapleton, analytically supported the need for the establishment of a war criminal unit within the AFP. The Lowy Institute paper argued that the formation of such a unit would be both more beneficial for identification and prosecution of potential war criminals and more economical for the government, with a war criminal unit being cheaper than the current system. Unfortunately, this advice was not heeded and the AFP today still has only limited capacity to investigate war crimes within its existing units.

Another legal legacy of the war crimes debate involves changes to the law regarding revocation of citizenship for those who lied about their past activities – such as the commission of war crimes – when they applied for immigration or citizenship. The Menzies Review noted that revoking the Australian citizenship of alleged war criminals on this ground was not possible because Australian law at the time only allowed such revocation for ten years after the act of providing false information on an immigration claim was committed. The Australian Citizenship Act 2007 removed this ten-year limitation period for offences involving false statements and representations used to fraudulently obtain citizenship or an immigrant visa.

Moreover, the legacy of the Nazi war criminals within Australia arguably had other legal effects. For example, this year bills were passed banning the display of the swastika and other Nazi symbols in Victoria and NSW. Victorian Attorney-General Jaclyn Symes noted that “the symbol does nothing but cause pain and division.” Arguably, the readiness of Australian governments to enact such measures to ban Nazi symbols is in some small part a by-product of the educational processes about Nazism and its impact in Australia that occurred during the war crimes debates that have regularly been a part of Australian public discussion since the 1980s.

Lasting impacts on Australian communities

Many communities are still grappling with the legacies left by Nazi war criminals in Australia, especially when former Nazis were highly integrated, influential, or otherwise prominent members of a community or group. These impacts are long-lasting and still present today.

For example, the residents of the city of Wollongong were recently forced to reconcile with the highly problematic past of a beloved and prominent community member, Bob Sredersas. In March 2022, it was shockingly discovered that Sredersas was a former SS member. Here are the salient facts of the case:

- Sredersas arrived in Wollongong in 1950 at 39 years of age, building a house on Hoskins Street, Cringila. He was employed as a crane driver at the Port Kembla steelworks. Having no family, he spent his spare wages on works of art.

- In 1976, he donated his entire collection of about 100 works to the city of Wollongong. This became the catalyst for the founding of the Wollongong Art Gallery.

- He has been celebrated by the city and the Australian Lithuanian community, with special plaques and special exhibitions and positive pieces within local media.

- Sredersas’ involvement with war crimes during WWII was not discovered until long after his death in 1982.

- In 2018, former Wollongong councillor Michael Samaras became suspicious of Sredersas’ story and began doing some research. In 2022, Samaras uncovered archival evidence which indicates Sredersas served in the intelligence arm of the Nazi SS during WWII, a unit which was in turn central to the systematic killing of 212,000 Lithuanian Jews.

- As a result of Samaras’ findings, the Wollongong Art Gallery is currently rethinking its legacy and structure and has removed the naming plaque within the gallery acknowledging him.

- Sredersas’ deep integration into the Wollongong community is indicative of the “safe haven” status Australia once provided and the contributions and impacts Nazi war criminals have had on Australia.

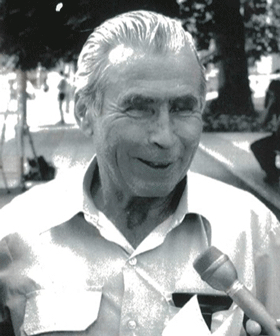

Karlis Ozols, the Australian chess champion who is alleged to have overseen the murder of 12,000 people (Image: Ashley Gilbertson)

Another prominent Nazi war criminal case which impacted a sector of Australian society involved Karlis Aleksandrs Ozols.

- Ozols allegedly served as a sub-commander in Minsk, Belarus during WWII, of the Arajs Kommandos, an elite killing squad of local Latvians who served under the command of the SS.

- It is alleged Ozols was commander of a unit numbering 110 men – whose function was the execution of Jews at the killing pits outside Minsk, Belarus. It was estimated that 12,000 people died as a result of Ozols’ command. Witnesses alleged that he also killed with his own hands.

- He came to Australia in 1949 and resided in Melbourne.

- The interesting aspect of Ozols’ case is that he was a public figure, a renowned chess player, well-known through the chess community in Australia and even beyond. Ozols was Victorian chess champion nine times and Australian champion in 1956. He was Australia’s representative at international chess tournaments.

- He often frequented a Latvian retirement home, in which his friend Konrad Kalejs (another alleged Nazi war criminal who also allegedly served in the Arajs Kommandos) lived. Upon learning of these visits, reporter Mark Aarons traced Ozols’ life, connecting him back to the massacres in Belarus.

- Ozols acknowledged his “sympathy for the German occupation of his country” to the Age newspaper but denied collaboration with the Nazis in extermination of the Jews.

- His status as a public figure known for his achievements in chess shows that not only former Nazis who kept low profiles were able to find a “safe haven” in Australia.

- Like Wollongong with Sredersas, the chess community in Australian has had to come to terms with the fact that one of its best known icons was allegedly a very senior Nazi war criminal with up to 12,000 deaths on his hands.

Conclusion

Nazi war criminal immigration to Australia has had long-lasting impacts on the community, both socially and legally. Australia’s Jewish community, with its large component of Holocaust survivors and their descendants, was significantly impacted by the discovery of the presence of these criminals, the initial official indifference to their presence, the later efforts to provide the tools to achieve some justice, and the ultimate failure of these efforts.

In the course of the debates about dealing with these criminals, Australia’s ideas about multiculturalism and immigration were developed and refined. Legal frameworks now in place make it much less likely that war criminals from current and future conflicts will be able to find Australia a “safe haven”. And despite the fact that all the alleged war criminals are now gone, as we see in places like Wollongong and the Australian chess community, the legacy they left behind still sparks difficulties, dilemmas and debates, and will likely continue to do so into the future.

Despite the failure of Australia’s efforts to bring the war criminals to justice, there is at least a case to be made that the effort to do so, and the debates it sparked, left Australia a more mature, more sensitive and aware nation.

Tags: Australia, Holocaust/ War Crimes