Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: Broken dreams

Apr 1, 2025 | Allon Lee

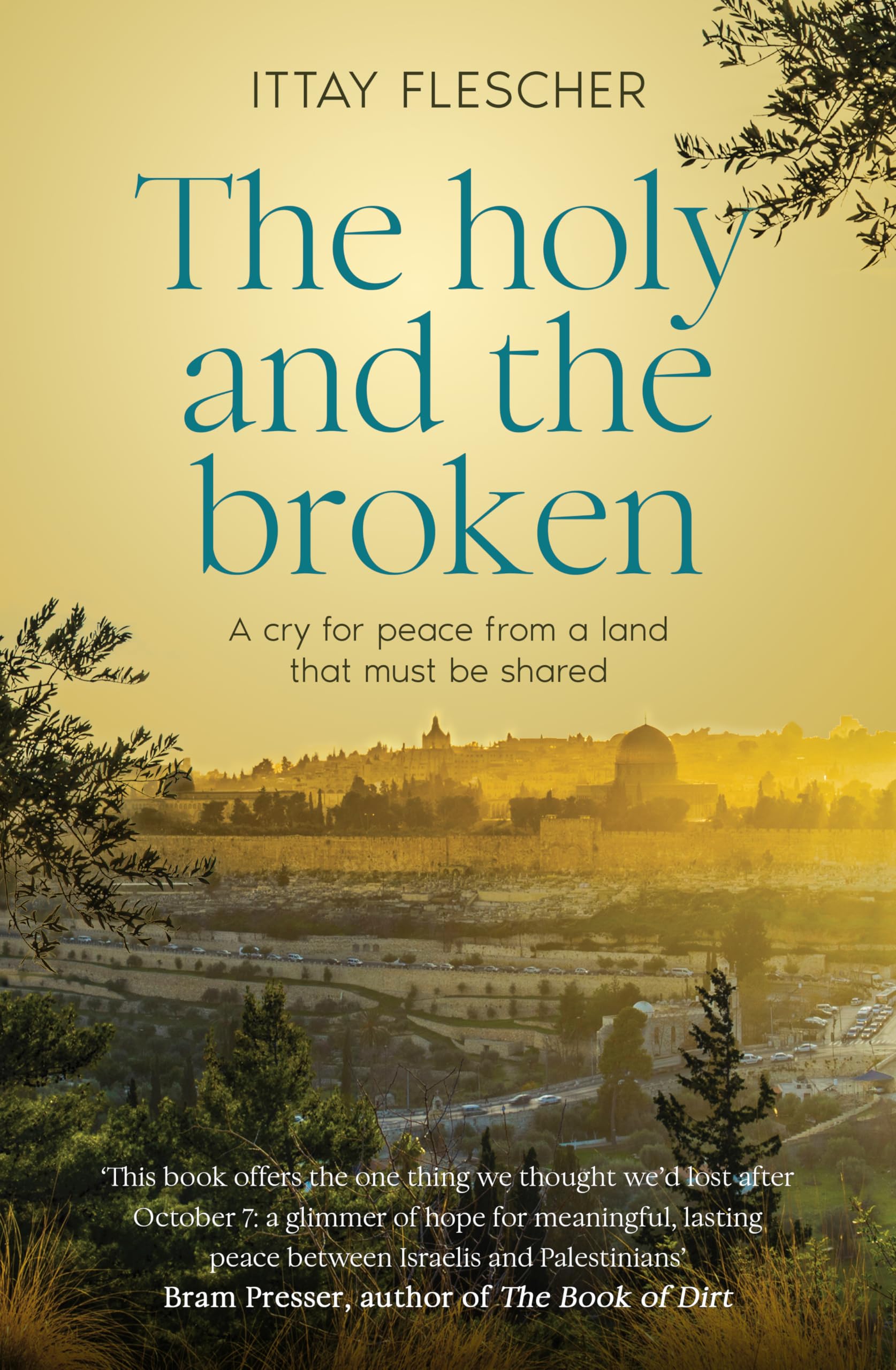

The Holy and the Broken: A cry for Israeli-Palestinian peace from a land that must be shared

Ittay Flescher

Harper Collins, Jan. 2025, 320 pp. A$36.95

There’s nothing worse than being labelled a fraier in Israel – that is, a ‘sucker’.

Given Hamas’ horrific bloodletting on October 7, 2023, many Israelis might feel that Flescher is treating them as frairim after reading his book, The Holy and the Broken: A cry for Israeli-Palestinian peace from a land that must be shared.

Journalist, interfaith activist and former teacher at Melbourne’s Mt Scopus Jewish day school, Flescher moved to Jerusalem in 2018. He began writing this book three days after October 7, arguing that 30 years after the Oslo process began, both sides’ leaders have failed to make peace, and a new approach is thus needed.

Flescher proposes a bottom-up, people-to-people peacemaking strategy informed by his work as educational director at Kids4Peace Jerusalem, which fosters trust-building between Israeli and Palestinian children.

His sections explaining how Kids4Peace breaks down barriers and encourages trust are very interesting.

Yet, as a reader, it’s hard to ignore the fact that, for the past 100 years, Palestinian leaders have treated their own people as frairim – rejecting numerous opportunities to create an independent Palestinian state in favour of perpetual conflict. But Flescher effectively appears to do just that. The book is littered with historical omissions and misrepresentations that minimise Israeli efforts for peaceful coexistence.

For example, Flescher states that “during the war of 1948, Israel conquered and forcibly relocated 200,000 Palestinians from the much larger Gaza district and pushed them into what became known as the Gaza Strip – as a result, there are now eight permanent refugee camps in Gaza.” Yet had Palestinian and regional Arab leaders accepted the 1947 UN Partition Plan instead of launching a “war of extermination”, no displacements would have occurred. And why, after 75 years, do these camps still exist, especially given Egypt ruled the Strip until 1967? Flescher doesn’t ask.

Flescher writes that he “mourns the loss of life” for those killed in the January 1948 bombing of the Semiramis Hotel in Jerusalem by the Haganah – a precursor to the IDF – along with the 2002 Passover bombing at the Park Hotel in Netanya, in which 30 Israeli civilians were killed. Many would argue no equivalence exists: The Semiramis was targeted because it was believed to be an important headquarters for Arab paramilitary activity when the Jews of Jerusalem were fighting for their survival. Nonetheless, the commander responsible was sacked. By contrast, the 2002 Park Hotel attack was a wanton act of terror targeting a Passover seder, launched shortly after Israeli PM Ehud Barak’s historic offer to create a Palestinian state.

Flescher’s claim that “In Jerusalem… [we] are fighting over one land that we each want exclusively, in its entirety” ignores key historical realities and differences.

Since Israel took control of east Jerusalem in 1967, religious groups have maintained authority over their own holy sites. Moreover, Israeli prime ministers Barak and Olmert both proposed peace deals that included sharing the city – offers Palestinian leaders rejected. But Flescher doesn’t seem interested in talking about this history. The Camp David Summit of July 2000, where Palestinian President Yasser Arafat rejected Barak’s peace plan before launching the Second Intifada, is buried in an appendix.

Flescher’s permanent solution is a shared homeland with two states based on 1967 borders, forming a confederation. Citizens could reside in either state as permanent residents, with free movement for all, Jerusalem as a shared capital, and security and economic matters jointly managed. He argues this model is superior because it fosters cooperation, while a traditional two-state solution would leave both nations deeply hostile.

But this shares the general flaw of the rest of the book – Flescher’s naïve insistence that Israeli-Palestinian hostility could quickly vanish if only both peoples listen to each other and decide it should.

The book is also highly critical of the responses of Israelis to the rising death toll in Gaza, post-October 7, but to his credit, Flescher at least quotes Israelis explaining this is the price that must be paid to remove the threat posed by Hamas.

Even with its factual problems and flawed vision for peace, Flescher’s book is thought-provoking. Ultimately, however, after October 7, it is hard to imagine Israelis accepting any solution which seems destined to leave them feeling like frairim again.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians