Australia/Israel Review

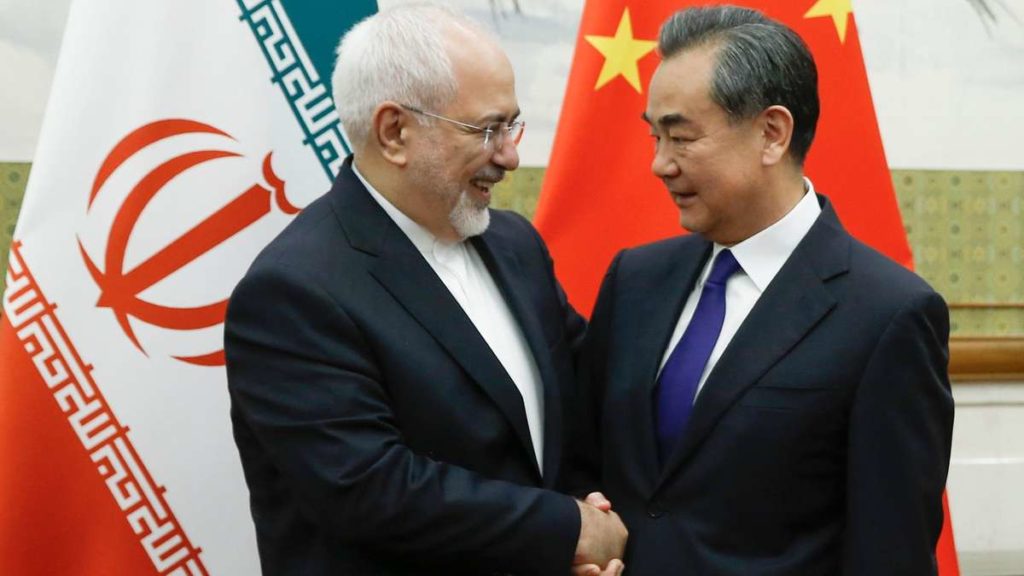

A Teheran-Beijing Axis?

Jul 27, 2020 | Amotz Asa-El

“Contacts are underway to establish normal ties with Afghanistan, as well as Israel,” reported Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai to China’s National Assembly in mid-1954.

The Korean War had ended the previous year, and the Chinese communist government was looking for ways to reach out to the West. Jerusalem, after some deliberations, decided to accommodate Beijing despite Washington’s dismay, and in early 1955, an Israeli diplomatic delegation was hosted in Beijing. However, China soon changed its mind, and the two nations remained estranged.

By 1964, estrangement had turned into hostility. That’s when the same Zhou Enlai emerged from talks in Cairo and declared “we are ready to help the Arab nations reconquer Palestine” promising Israel’s enemies “anything you ask: weapons and volunteers.”

The volunteers never came and the weaponry of Arab armies remained mostly Soviet-made, but the Chinese attitude remained a thorn in Israel’s side. It was the inversion of what was happening at the other end of the historic Silk Road, in Iran, whose relations with Israel were flourishing at that time.

In 1979, by sheer coincidence, China and Iran both made historic U-turns. The former abandoned major elements of its anti-Western communism while the latter shifted to anti-Western Islamism. Now the two ancient nations are both reportedly at the cusp of yet another change of course, potentially at Israel’s expense.

With Beijing facing what it sees as an economically belligerent White House, and with Teheran straining under American-led sanctions, Chinese and Iranian representatives have held talks in recent months over an ambitious long-term deal that would focus ostensibly on trade, but create serious potential geopolitical consequences.

According to a draft agreement obtained by the New York Times, the plan involves nearly 100 civilian projects including airports, seaports, metro systems, fast trains, and telecommunications infrastructure. Spanning 25 years, Chinese investments would average US$16 billion (A$22.9 billion) annually, in return for which Iran would ship oil to China at discounted prices for the deal’s duration.

Militarily, the document did not include transfers of hardware, but it did mention intelligence exchanges, joint exercises, and joint arms development. At this writing, there is no firm indication of when the deal might be signed, though some reports suggested it could be scheduled for next March.

In recent years, there have been other strategic deals between the two countries, most notably one signed in 2016 for joint exercises and cooperation in what they called “fighting terrorism.” However, in terms of its scope, duration and cost, this new agreement would be on an entirely different scale. The question therefore is what in it might materialise, and what it means for the West generally, and for Israel in particular.

Strategically, there is logic in the reported blueprint.

Iran’s needs are obvious: the Islamic Republic is beset by international sanctions, inflation, unemployment, and industrial stagnation. A long-term partnership with China offers Iran a priceless alternative to European and American investment. As a bonus, it can also potentially create a counterweight to America’s naval dominance between the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf.

Such hopes were asserted publicly by Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in a speech delivered on July 7, where he called on Lebanon to forego a much-needed International Monetary Fund loan, and seek credit from China instead. The Iranian-backed Nasrallah added that China is eager to restore Lebanon’s defunct coastal railway.

From China’s viewpoint, a strategic partnership with Iran would offer its vast industrial sector, the world’s leading oil importer, a smooth and long-term supply of petroleum. Meanwhile, the public works projects would fit well into the Belt and Road Initiative, through which China is building infrastructure projects across Asia and the Pacific, through the Indian sub-continent and into the Middle East – a program which aims to expand Chinese international influence, as well as provide contracts for state-linked Chinese firms.

Then again, in some respects, the prospective deal makes less sense.

First, Iran’s oil is hardly crucial for China, which has a surplus of solid suppliers, from Russia and Malaysia to Saudi Arabia. Moreover, China is investing billions in fracking, and its shale deposits are believed to be vast, possibly larger than America’s.

Second, with oil prices already at historic lows – due both to America’s intense fracking and the coronavirus effect – selling crude to China, at even lower prices, might prove economically unworkable for Iran.

Thirdly, some in Iran are concerned that China’s projects might compromise Iran’s national interest, and possibly also its sovereignty.

Rumours that the prospective deal includes ceding Iranian islands in the Persian Gulf to China were denied in early July by Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson Abbas Mousavi, after former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said in a speech that the proposed deal with China was “suspicious”.

Such concerns about Chinese designs are not unique to Iranian nationalists, and indeed are shared in Western capitals, where Beijing’s rapidly expanding involvement in global infrastructure projects is seen as risky economic hyperactivity at best, and a geopolitical power grab at worst.

In Iran, there are concerns that a deal will involve a Chinese naval presence within, and military presence alongside, the Strait of Hormuz, which would govern that passage from the Arabian Sea to the Persian Gulf. Whatever such a presence might mean for China and Iran, the US would not be at all happy to see a Chinese base located in a key geopolitical chokepoint through which most of the Middle East’s oil passes to the outside world.

Just what China is out to achieve in Iran, and what it is prepared to pay for that, remains unclear.

In all likelihood, one component of Beijing’s thinking is not about Teheran, but about Washington. Feeling pressured by US President Donald Trump, China might be pretending to cook up an Iranian deal only to convince Trump to change his course on China – for instance by ceasing to confront the aggressive Chinese expansion in the South China Sea.

Whether or not this is part of an arm-wrestle with the US, China is out to establish a presence along what it calls the maritime Silk Road. That is why it stationed a military unit in Djibouti, at the Horn of Africa, in 2015, and why Beijing has signed long-term leases for ports from Malaysia through Sri Lanka to the Maldives.

Then again, the days when superpowers were prepared to pay fortunes to maintain Middle Eastern alliances, the way the USSR did with Egypt in the 1950s and with Syria in the 1970s, are almost certainly over. China wants cash for anything it offers. This is the likely reason the Iranian-Chinese deal apparently does not include arms supplies. Iran can’t currently afford the jets, tanks and battleships which its military craves and which China can deliver, the sanctions notwithstanding.

As China did during the Iran-Iraq War, when it sold arms to both sides, it is prepared to sell almost anything to almost anyone, but being the good capitalist it has become, it will only do so for hard currency. Iran does not currently have any to spare.

Does this mean Israel should not be alarmed by the Chinese-Iranian trade talks and purported deal? Sadly, it does not.

It is true that since establishing diplomatic ties in 1992, China and Israel have become close commercial partners – so much so that over the half-decade from 2014 to 2019 their bilateral trade nearly doubled, from A$12.6 billion to A$21.75 billion.

Moreover, Chinese companies were involved in building major Israeli infrastructure projects, including the Tel Aviv subway and a new seaport in Haifa, while Israel’s leading universities have built five academic centres in major Chinese universities.

These civic and economic partnerships will not be directly affected by whatever China does to help Iran economically. However, should China set out to replace the Iranian army’s ageing aircraft, armour, and boats, Israel will have to treat such an effort the way America treats China’s commercial conduct: as a strategic threat.

Tags: China, Iran, Israel, Middle East