Australia/Israel Review, Featured

The options for a ruling coalition

Sep 25, 2019 | Michael Bachner

The final results of the Sept. 17 elections establish that no candidate or party has a straightforward path to forming a governing coalition of at least 61 lawmakers in the 120-member Knesset.

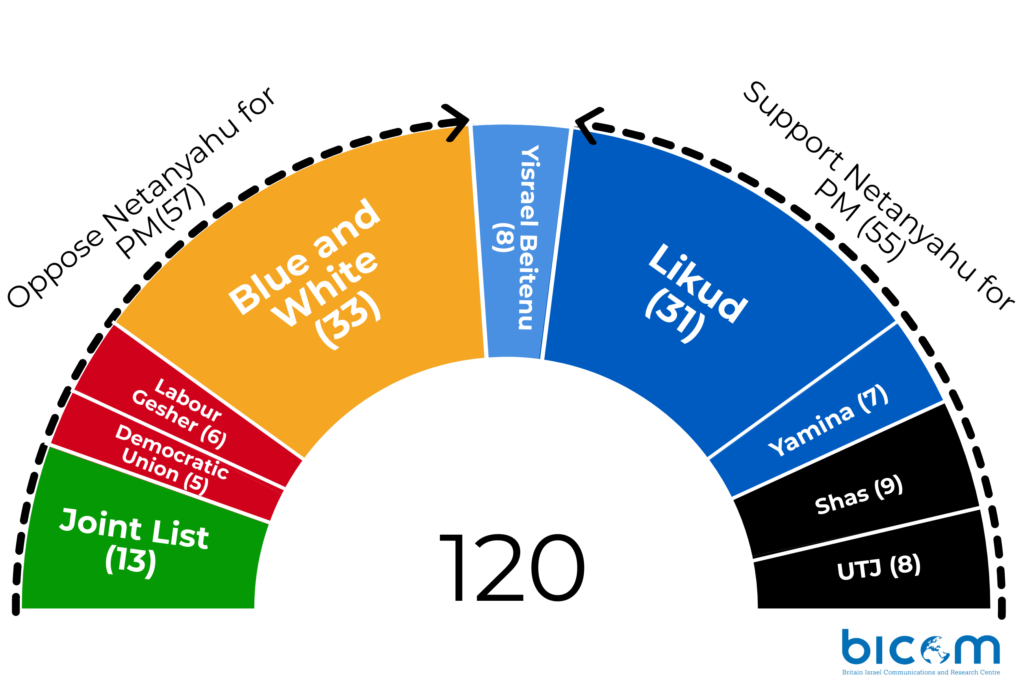

The next Knesset looks like this: The Blue and White centrist alliance has 33 seats, just ahead of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s right-wing Likud with 31. Next is the Joint List alliance of Arab-majority parties with 13 seats. Then comes the ultra-Orthodox Shas with nine seats, followed by United Torah Judaism and the secular right-wing Yisrael Beitenu with eight each. Bringing up the rear are Yamina with seven, Labor-Gesher with six and the Democratic Camp with five.

The right-wing religious bloc has a total of 55 seats, the center-left has 57, putting Avigdor Lieberman in kingmaker position with his Yisrael Beytenu party’s eight seats.

What could the next coalition look like? Here are the options.

Unity government

A coalition comprising both Likud and Blue and White was urged by Lieberman and Blue and White on the campaign trail, and remains the most likely outcome of the election.

However, there are many shapes such a government could take, and it leaves open the most significant question of who would be prime minister. That is subject to coalition negotiations that will take weeks, if not longer.

A unity government could see Netanyahu continue as premier or Blue and White’s Benny Gantz take over that role, but the most likely outcome would be some sort of rotation whereby one of them would serve as prime minister for the first couple of years, then hand over to the other. In that case, the question remains who will be first.

A unity government could also include Likud without Netanyahu, as Blue and White has insisted. The premier is facing corruption charges in three cases, including a bribery charge in one, pending a hearing, which is to be held on Oct. 2-3, leading the centrist party to declare it won’t join a coalition with him. Likud, however, has thus far stood firmly behind its longtime chairman.

However, if Likud ends up deposing Netanyahu, a whole new question opens up: Who will take the reins of the party, whose leadership has been monopolised by one man for a decade and a half? It could be its number two, Knesset Speaker Yuli Edelstein, or Foreign Minister Israel Katz, Public Security Minister Gilad Erdan, Netanyahu’s internal rival Gideon Sa’ar, or someone else.

Another question is whether the unity government will include Yisrael Beitenu. Between them, Likud and Blue and White have enough Knesset seats to form a coalition, rendering Lieberman’s party unnecessary, although politicians usually prefer to make their coalition as broad as possible. Lieberman has said he would be okay with a unity government even if he is excluded.

Other parties could also potentially join a unity government, although that could raise objections within either Likud or Blue and White.

Right-wing government with Lieberman

The coalition that ruled Israel until Yisrael Beitenu bolted in November 2018 included all the right-wing and religious parties. However, after Lieberman turned down all of Netanyahu’s offers to form such a government again in the aftermath of the April elections, triggering the current vote, it is extremely unlikely that he will now agree to renew those partnerships.

There is a small chance, however, that the ultra-Orthodox parties will balk at going to the opposition and instead opt to compromise with Lieberman over the latter’s demand to pass unaltered a bill regulating the military draft of ultra-Orthodox seminary students, which thus far has been a nonstarter for them.

Whether even that concession would now satisfy Lieberman is far from certain. Post-election, he has remained adamant that a unity government is the only conceivable option.

Right-wing religious government plus Labor

During the campaign, there have been stubborn rumours that Amir Peretz, chairman of the alliance between Labor and Orly Levy-Abekasis’s Gesher, could lead the party into a right-wing Netanyahu government. Labor previously entered such a government in 2009, but it may be electoral suicide this time around after Peretz repeatedly insisted that under no circumstances would that happen, going so far as to shave off his moustache after 47 years to get his point across.

Indeed, while Likud reached out to Peretz after the results of the elections began to emerge, the latter made it clear that he was not interested in joining a Netanyahu-led coalition.

Centre-left government

Likud warned in its campaign that both Lieberman and Joint List chairman Ayman Odeh had spoken about recommending Gantz as prime minister. However, a government that includes both those parties, which despise each other, seems impossible. Lieberman has said he won’t join a coalition with the Arab parties, and most factions within the Joint List reacted with outrage to Odeh’s comment about possible political cooperation with Blue and White.

Gantz has the option of forming a minority government with outside support from the Arab parties, a course advocated by Democratic Camp’s Ehud Barak following the election, but neither side would be thrilled with that arrangement and the resulting government would be on extremely shaky ground.

Another option could be for the ultra-Orthodox parties to join Blue and White, Labor-Gesher and Democratic Camp. Similar centre-left governments with the Haredi parties existed in Israel decades ago, but Shas and United Torah Judaism (UTJ) have in recent decades become automatic supporters of Likud.

Another problem is that those parties add up to a very narrow majority – not a recipe for a stable coalition.

(Yet) another election

In the unlikely scenario that the deadlock will continue and produce a third national vote in less than a year – an option nobody wants – it will extend the period of time in which national leadership is pretty much on hold, cost additional billions of shekels, and further erode public interest in a process that is likely to again produce an indecisive result.

Many parties, as well as President Reuven Rivlin, have promised to do everything to avoid another election, and Lieberman has vowed to deny any such proposal the parliamentary majority it would need to pass.

Which brings us back to where we started: The only way to achieve a stable majority government would be for at least some party or parties to compromise on at least some of their campaign promises and imperatives.

The question is who is going to be the first to blink.