Australia/Israel Review

Israel’s odd coalition and the Arab world

Oct 26, 2021 | Amotz Asa-El

Four months after journeying from the opposite ends of Israel’s political rainbow to set up camp in a shared ruling coalition, the leaders of the parties making up Israel’s diverse Government have not changed their ideological spots.

A reminder of their disparate backgrounds and ideologies emerged when Defence Minister Benny Gantz met Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah on Aug. 30.

Considering that Abbas had not met an Israeli cabinet member since 2014, the meeting marked the end of an era in which Jerusalem largely sidelined Abbas. However, the attitude of the centrist Gantz was one thing, and that of right-wing Prime Minister Naftali Bennett was another.

“I don’t see the logic in meeting Abu Mazen,” he told Ynet, referring to Abbas by his unofficial nom de guerre. “He is suing our soldiers in The Hague and he accuses the IDF’s commanders of committing war crimes,” said Bennett. “My position is different,” he explained, “I oppose [establishing] a Palestinian state.”

Bennett’s stance is shared by three of the coalition’s eight partners, and opposed by the other five, who espouse a two-state solution. That is why a delegation from the liberal Meretz faction, including Bennett’s Health Minister Nitzan Horowitz and Regional Cooperation Minister Isawi Freij, also met with Abbas in Ramallah on Oct. 3.

Still, while the coalition remains deeply divided on the Palestinian issue, its partners’ agreements on other issues, including other Arab affairs, seem for now stronger than their disagreements. So also does the spirit of compromise that their improbable cohabitation demands.

Compromise is a prerequisite for any governing coalition, but in Bennett’s Government, which ranges from West Bank settlers to Islamist activists, compromise is a daily necessity, particularly on Arab affairs. The results have been rather surprising.

One test loomed days after the Government’s establishment, when the deadline arrived for the annual renewal of a legal stipulation that prevents the automatic naturalisation of Palestinians who marry Israelis, for fear of facilitating terrorist infiltration.

While the issue pitted one of Bennett’s coalition partners, the United Arab List (UAL), against his closest ally, hawkish Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked, a deal was negotiated by Shaked and Arab minister Isawi Freij. It was based on a formula whereby 1,600 Palestinian residents of Israel would have their status upgraded from tourists to temporary residents in exchange for the law’s renewal.

The opposition managed to derail the compromise in the Knesset plenary, and it is now being renegotiated. However, the deal showed that the new coalition can produce understandings even between the starkest antagonists, and even on particularly prickly issues.

On a less explosive, but even more interesting issue, the UAL voted for a bill that legitimises medicinal cannabis use. The UAL initially opposed the idea, citing Islam’s opposition to addictive drugs, but received permission from its spiritual leaders to back the bill’s first reading, provided its final version leaves no openings for non-medicinal use.

Even more improbably, Knesset Interior Committee Chairman Walid Taha of the UAL said that an Israeli military operation in Gaza would not necessarily bring down the Government. “An alternative government would only be worse” from a Palestinian viewpoint, he told Channel 12’s “Meet the Press”.

Lurking beyond all this pragmatism is the central Arab-related issue for the Bennett Government: crime in Israel’s Arab-majority communities.

In recent years, Israeli Arab cities and neighbourhoods have become hotbeds of crime in almost all its forms: gang wars, protection rackets, drug trafficking, homicide, fraud, prostitution and gambling. The number of Israeli Arabs murdered by other Israeli Arabs rose from a record 95 in 2019 to 106 last year, and this year it is set to be even higher – there were 100 such murders by early October.

The Bennett Government is united in its determination to address this scourge, which is caused by a mixture of inadequate policing, low social investment and a culture of family feuds and so-called honour killings.

An ambitious NIS 2.4 billion (A$1.01 billion) plan devised by a team headed by Bennett and Internal Security Minister Omer Bar-Lev (Labor), in cooperation with the UAL leader Mansour Abbas, includes deploying 1,100 additional police officers in Arab towns; opening new police stations in several such towns; establishing a special police unit for the prevention of crime in the Arab sector; and creating departments for combating street violence, protection rackets and financial fraud in the Arab sector.

Just how much of all this will happen and how successful these efforts will be remains to be seen, but there is no doubt that the Bennett Government is truly motivated on this front, and also united, for several reasons.

Firstly, the crime situation has indeed become a national crisis about which practically all citizens care. Secondly, for the coalition’s Arab component it is electorally crucial – it was their key justification for breaking old taboos to enter the governing coalition. Thirdly, the rest of the Government would like to see civic issues, as opposed to nationalist ones, dominate Israeli Arab politics. And lastly, crime in the Arab sector is one big and urgent issue on which this eclectic Government can demonstrate its ability to work together without ideological disagreements.

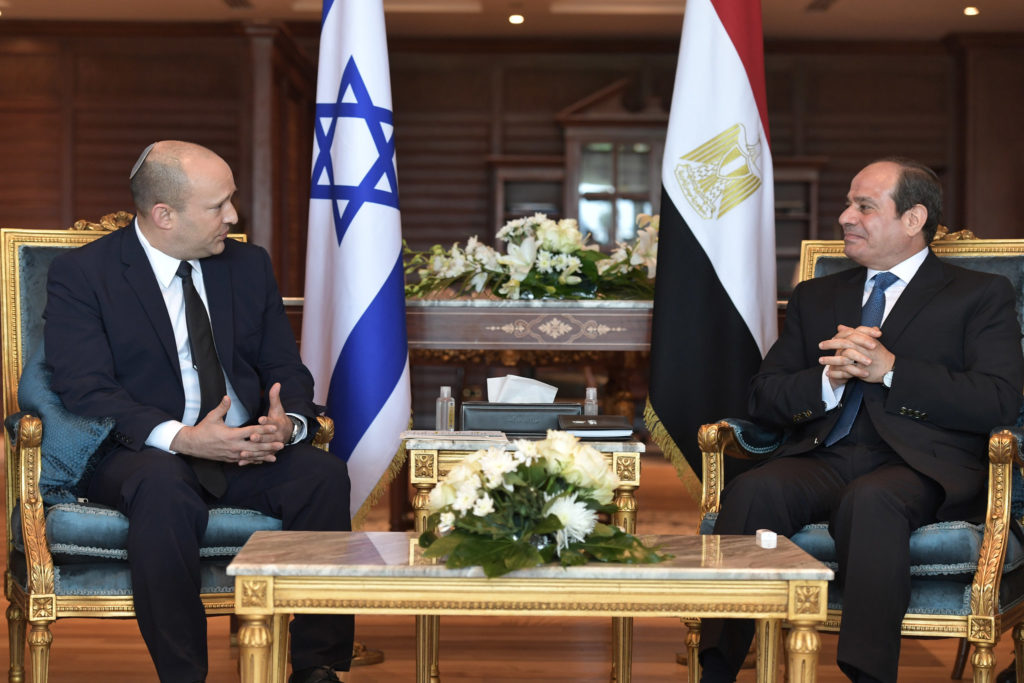

Israeli PM Naftali Bennett with Egyptian President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi at Sharm el-Sheik (Credit: Israel GPO/ Flickr)

Meanwhile, this urgency and common cause on the domestic front, and impossibility to harmonise on the Palestinian front, do not mean that nothing is happening on the third front of Israeli-Arab relations, the regional.

Bennett inherited a rapidly developing thaw in Israel’s relations with the broader Arab world: In the east, normalisation agreements with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain; in the west, a similar deal with Morocco, and in the middle, close cooperation with Egypt.

The new prime minister has picked up from where his predecessor, Binyamin Netanyahu, left off.

In June, Foreign Minister Yair Lapid arrived in the United Arab Emirates, and formally opened the Israeli embassy in Abu Dhabi.

In July, Jordan’s King Hussein, whose relations with Netanyahu were rocky, hosted Bennett in his palace. The meeting was unofficial and only became known after it had been held, but diplomats say relations between the two countries have been improving since the change of government. Israel later signed a deal to greatly increase the amount of water it supplies to Jordan.

In August, Lapid visited Morocco, and formally opened the Israeli mission in Rabat, which, according to the Abraham Accords, will later become an embassy. Lapid was accompanied by the Moroccan-born Welfare Minister Meir Cohen, whose family moved to Israel in 1961 when he was six.

In September, Bennett visited Egypt and met President Abdel Fatah el-Sisi in the Red Sea resort town of Sharm el-Sheik. It was the first time in a decade that the two countries’ leaders have publicly met in Egypt. Bennett was greeted warmly, a reflection of the close cooperation between Egypt and Israel in fighting terror in general, and in the Sinai Desert in particular.

Later that month, Lapid landed in Bahrain, where he met with King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa, and also inaugurated the Israeli embassy in Manama. Lastly, in October, Lapid conferred in Washington with his American and Emirati counterparts, Antony Blinken and Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed.

Added up, these events suggest that the process of normalisation between Israel and the broader Arab world has not been affected by the change of government in Israel and, if anything, has accelerated. The common denominator among all these Arab countries is that, like Israel, they feel threatened by Islamist terror, and by Iran.

While engaging in all this diplomatic hyperactivity, Lapid is cultivating the worldly profile that his current job requires and that he also hopes will help benefit his future career.

His turn to succeed Bennett as prime minister is now less than two years away, according to the coalition agreement, and the outgoing and telegenic Lapid has aroused curiosity in world capitals. In some places, there are reportedly also hopes that he will make moves on the Palestinian front that Bennett would not.

This is likely wishful thinking. The alliance between Bennett and Lapid is the most solid element in Israeli politics right now, and attempts to drive a Palestinian wedge between them will probably fail.

Opponents of Bennett’s hard line on the Palestinian front will therefore have to make do with what he has been up to on Israel’s domestic and regional fronts in dealing with the Arab world – where the strangest coalition Israel has ever had is, so far, delivering no less than previous governments, and possibly more.

Tags: Abraham Accords, Israel, Middle East, Palestinians