Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Is your charitable donation supporting terrorism?

Sep 2, 2020 | Doron Goldbarsht

When we hear the term ‘terrorist financing’, we usually think of those who deliberately provide support for terrorists to prepare for attacks, undergo special training, purchase weapons or explosives, travel to planning meetings, and communicate with their collaborators.

Lone offenders and some small terrorist groups manage to sustain their campaigns on a shoestring budget. They have few members to train and equip, they rely on simple weapons such as knives, and they are not subject to the high and indirect costs of developing and maintaining a sizeable organisation. However, more sophisticated terrorist organisations require quite substantial amounts of money in order to survive and develop over longer periods of time. These groups tend to operate in a way that assumes some degree of social responsibility for their supporters by establishing a ‘humanitarian wing’ alongside the ‘military wing’, which complicates identifying funding for a terrorist group.

Financing terrorist organisations

The day-to-day activities of terrorist organisations require an arsenal. While a boxcutter and a plane ticket can enable a terrorist attack, creating and sustaining an atmosphere of sustained fear and impeding the daily lives of ordinary citizens requires a substantial cache of weapons and trained people to use them.

Terrorist organisations are often able to access the same weapons used by military forces; for example, Hezbollah is equipped with unmanned aerial vehicles and advanced missile technology. Over the years, Hamas has fired thousands of rockets of varying types, with an average cost of US$800 (A$1,112) each. The tunnels that Hamas has dug from Gaza into Egypt and Israel are estimated to cost US$140 million (A$195 million) a year. Al-Qaeda possesses anti-aircraft missiles and has even tried to build an atomic bomb, including attempting to buy a component from South Africa for US$1.5 million (A$2.09 million) in 1993. Blocking the funds required for terror-related goals is therefore crucial in combating terrorist activity.

Hezbollah is thought to receive about US$700 million (A$973 million) annually in funding from Iran – but has numerous other sources of revenue as well. The estimated annual budget of Hamas is approximately US$70 million (A$97 million). Al-Qaeda is understood to receive approximately US$50 million (A$69 million) per year in foreign donations. During the war in Sri Lanka (1983-2009), the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam are believed to have received between US$100 million and US$200 million (A$140 million to A$279 million) annually. Finally, the Colombian organisations FARC and Movimiento 19 de Abril are said to have received US$150 million (A$208 million) a year during the 1980s.

Financing the humanitarian wing

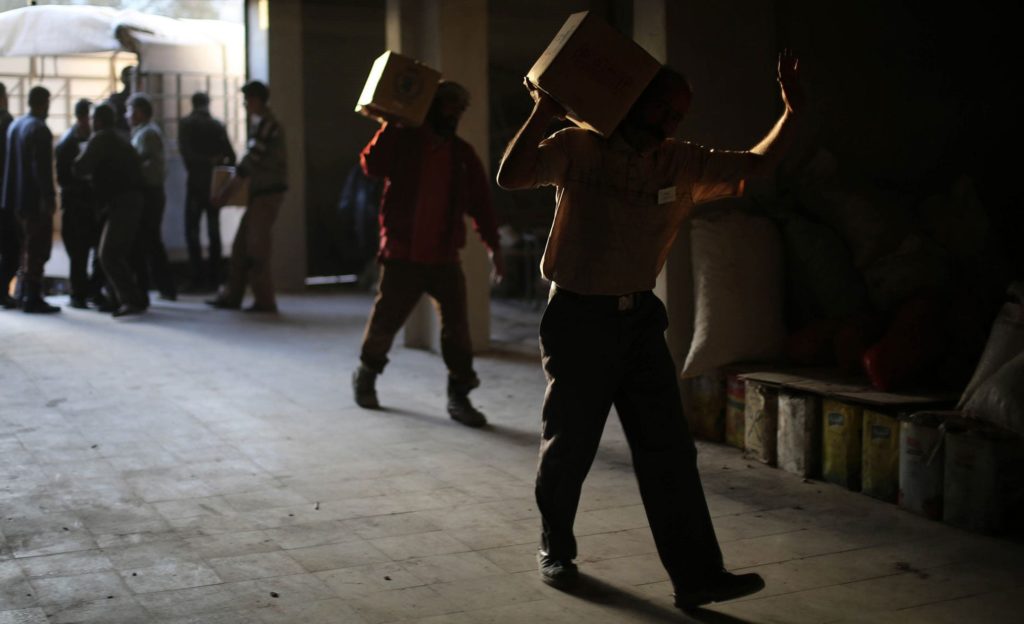

The “humanitarian wing” of a large terrorist organisation generally provides a range of social services to the local community. This might include assistance to the poor, orphans and widows (who are often poor, orphaned or widowed due to the operations of the military wing of the organisation), as well as educational and health care services. Money directed to the welfare programs of the “humanitarian wing” of a terrorist group supports and helps perpetuate terrorism by generating loyalty and spreading the aims and ideals of the organisation among the public for which it ostensibly cares.

The humanitarian wing is also a tool for recruitment to the military wing. Teachers and religious leaders, paid for through the humanitarian wing, champion the goals and ideals of the organisation. Through promises of reduced tuition fees or university scholarships, people are enticed to join the organisation and are then offered financial compensation to commit terrorist acts. Thus, whether deliberately or inadvertently, the humanitarian wing serves to strengthen the military wing of the organisation.

To illustrate, in southern Lebanon, where the national government maintains only a token presence, Hezbollah-funded schools and hospitals serve thousands of the region’s mostly poor residents. The residents, in turn, revere the party and its still-active armed wing. In this way, funding received by the humanitarian wings of Hezbollah and other terrorist organisations is inextricably bound with support for their military activities – despite the fact that the costs of the military bodies are often relatively small in comparison to the humanitarian expenditure.

Terrorist organisations need money – a good deal of it – and charities are one way of securing it.

The role of charities in terrorist financing

Terrorists can misuse charities in a variety of ways. They can funnel money from a local organisation supported by charity to an overseas partner that funds terrorist acts. They can transport weapons in a charity’s vehicles, or store weapons at its premises. With or without the charity’s knowledge, they can raise funds in the charity’s name and use those funds for terrorist purposes. Alternatively, they can establish a charity for a specific ostensible purpose and then use the charity’s funds to finance terrorism.

The factors that allow charities to achieve their humanitarian outcomes make them vulnerable to being misused by terrorists. Charities may have a global presence that provides a framework for international operations and financial transactions. Many charities work in areas that are prone to terrorist activity and may provide humanitarian responses in locations where there are no banks, so they need to deal in cash. Furthermore, they often have complex financial operations and many donors, requiring them to deal with multiple currencies and small transactions, making it difficult to identify suspicious transactions.

Australian charities have a long history of helping the vulnerable and disadvantaged, both at home and abroad. Our 54,000 registered charities have a combined annual income of over A$134 billion and assets totalling A$267 billion. More than 8,000 of these charities conduct activities outside Australia, sending A$1.5 billion in donations and grants overseas each year. Many of them operate in, or send funds to, conflict zones and other unstable regions. Thus, charitable donations from well-intentioned Australians can end up anywhere – including in the hands of the humanitarian wing of a terrorist organisation.

In 2015, the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force – the global standard-setter for countering money laundering and terrorism financing – found that Australia’s charitable sector and its regulatory framework were not in compliance with global counter-terrorist financing standards. In response, Australia undertook a comprehensive risk assessment of its charity sector. It identified the features and types of Australian charities that are likely to be at risk of terrorist financing: legal entities primarily based in New South Wales, those with low annual turnover, those that were only recently established, those that are service-oriented, and those that undertake transactions with countries with high terrorist financing risks. The main terrorist financing threats to charities in Australia include the diversion of legitimate funds by senior charity personnel to finance offshore terrorist activity, attempts to infiltrate charities by terrorist groups, and the use of online platforms to solicit funds for terrorist purposes.

Australia has since then significantly improved its compliance with the global standard, but a few deficiencies in the regulatory regime remain. The registration of charities is still voluntary, although it provides access to tax concessions and other benefits. Unregistered charities are generally subject to other requirements that may prevent terrorist financing abuse; for example, they may be unable to hold assets or open a bank account.

Australia has identified higher-risk charities, but it remains in the early stages of reviewing the legislative framework. Moreover, there are concerns that some smaller charities, identified as potentially high risk, are not subject to adequate monitoring.

How can we identify an illegitimate funds transfer involving a charity? Until it is spent, how do we know whether a donation will finance baby formula or terrorism?

It remains difficult to determine whether charitable funds are used to finance terrorism. What is clear, however, is that we cannot rely on an artificial distinction between the various components or “wings” of a terrorist organisation. Funds directed to the humanitarian wing contribute to the operations of the military wing. Therefore, funding the humanitarian wing should be seen as an indirect method of financing the terrorist activities of the military wing. A dollar donated to purchase baby formula could potentially allow the organisation to spend a dollar on bullets.

Targeting sources of funding is critical when attempting to limit terrorism. The basic premise is deceptively simple: smother the source of oxygen and a terror cell will die. However, the sources of funding for a terrorist organisation may be multifaceted and international. Charities are only one of them, but they are one whose vulnerabilities Australia can and should address as a matter of priority.

Doron Goldbarsht is a lecturer in the School of Law at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia and a member of the Optus Macquarie University Cyber Security Hub. Dr. Goldbarsht is the author of the new book Global Counter-Terrorist Financing and Soft Law: Multi-Layered Approaches (Elgar, 2020).

RELATED ARTICLES

AIJAC welcomes decision to list Hizb ut-Tahrir as a prohibited hate group