Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Counter-terrorism and coalition politics

Nov 27, 2019 | Amotz Asa-El

Will the Gaza conflict end Israel’s political deadlock?

Baha Abu al-Ata went to bed on the night of November 11, in his home in Gaza’s Sajaiyeh neighbourhood – the same neighbourhood where, as a 13-year old, he had joined Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) almost three decades previously. By the next morning he was dead.

Having spent years organising, ordering and delivering rocket attacks on Israeli towns, the 42-year-old division commander in the Iranian-backed terror group was hit by a rocket through his bedroom window. The projectile, fired by an unspecified Israeli aircraft at 4:20 am, found him and his wife asleep.

Six minutes earlier, and 300 kilometres to the northeast, rockets reportedly struck a house in Damascus, injuring PIJ treasurer Akram al-Ajouri, and killing his son and a bodyguard.

Unlike the attack in Gaza, which the IDF formally confirmed, Israel has remained mum about the attack in Damascus. Regarding al-Ata, the IDF said that he was busy organising new attacks on Israel, using rockets, snipers, and drones, and thus considered “a ticking time bomb.”

The attacks touched off a chain reaction, on multiple planes.

The Iranian-armed, trained and funded PIJ, which vows to destroy Israel and build an Islamist state on its ruins, responded by firing more than 400 rockets to Gaza’s east and north into Israel over the next three days. Most were intended to hit Israeli towns nearby and some aimed at reaching all the way to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. None did.

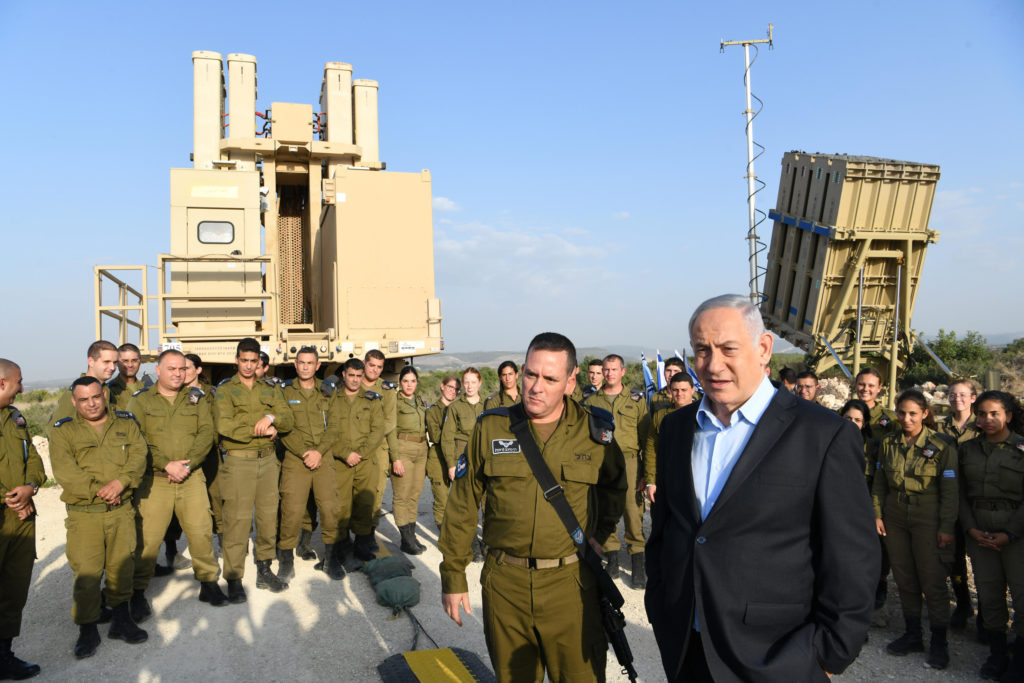

Israel’s Iron Dome anti-missile batteries intercepted most of the rockets heading for populated areas, while the Israeli public, following instructions from the Homefront Command, avoided serious physical harm, excepting a small number of light injuries.

Still, there was other damage, most notably the shuttering of schools in dozens of towns, including for one day in Tel Aviv, following intelligence that PIJ was planning to time their fire deliberately for when students would be on the way into or out of schools.

Economically, the attacks damaged numerous businesses in the rockets’ range. One industrial plant, mattress maker Hollandia in Sderot, sustained a direct hit that torched NIS 70 million (A$29.6 million) worth of merchandise.

The IDF, meanwhile, hit several PIJ squads as they were preparing to fire rockets, killing more than 20 militants. Experts said the attacks unveiled surveillance abilities the IDF had previously lacked, as did the surgical strike on Abu al-Ata, which found him in a single room in a three-storey building after verifying the absence of the knot of civilians with whom he normally made sure he was surrounded.

The conflagration triggered Egyptian efforts to broker a ceasefire as PIJ’s leader, the Damascus-based Ziad Nahala, arrived in Cairo for talks. On Thursday, Nov. 15, PIJ claimed a ceasefire agreement had been reached, only to soon resume its rocket attacks later that day. By the night of Friday, Nov. 16, the fire seemed to have subsided, until two rockets were fired at Beersheva, and intercepted by Iron Dome.

Though that specific final pair were fired by Hamas, that organisation had previously stood aside throughout the confrontation, and its representatives were in fact chased away from al-Ata’s mourners’ tent when they arrived to pay condolences.

Hamas, throughout its 12-year rule of Gaza, has repeatedly attacked Israeli towns, yet refrained from following PIJ’s lead, and stood by as Israel attacked its rival’s fighters, bases and materiel.

Israeli analysts suggested that Hamas was not interested in a round of violence at this time, realising that the public in Gaza is exhausted and expects its governing organisation, first and foremost, to deliver basics like fuel, food and work. Hamas thus wants to maintain the flow of Qatari payments into the strip, money that enters only during calm periods.

PIJ, by contrast, has no governmental duties or aspirations, and is perceived by Hamas as an irresponsible political saboteur.

This effective abandonment by Hamas, along with the new targeting abilities the IDF has displayed, together constitute a severe blow to PIJ.

Worse, from its viewpoint, the targeted killing of PIJ’s most important military leader by Israel led to no international rebukes, reflecting the fact that not only in Washington and Brussels, but also in Moscow, Cairo and Riyadh, political leaders are strongly displeased with Iran’s meddling in conflicts throughout the Middle East.

Hamas is aware of this, recalling previous damage inflicted on the Palestinians when their leaders chose problematic allies, most memorably Yasser Arafat’s backing of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The extent to which Hamas cares about international opinion is unclear, but it clearly wants the support of Arab governments, and those right now mostly view Iran as a strategic threat.

Meanwhile, back in Israel, the fighting quickly impacted the ongoing complex political situation created by September’s inconclusive election.

The first result of the Gaza conflict was visible harmony between Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and his rival, Benny Gantz. The latter led previous fighting in Gaza while he was IDF Chief of Staff in 2011-2015. The Prime Minister with whom he worked every day over those four years was the same Netanyahu he now faces across the political aisle.

As the IDF prepared to launch the strike he had ordered on their advice, Netanyahu met with Gantz and briefed him about the approaching operation. Gantz and his Blue and White party gave the attack their full support, a stance that was then also adopted by the two Zionist Knesset factions to their left, Labor and the Democratic Union.

The one faction that did not toe this line was the Joint List, a federation of Arab parties, whose head, Ayman Odeh, accused Netanyahu of setting out to “leave scorched earth in a desperate attempt to remain in office.” His colleague, MK Ahmad Tibi, said the IDF’s operation was “a campaign to save Netanyahu.”

The charge was flatly dismissed by Blue and White’s lawmakers, who justified the operation’s aim, means, and timing, and defended Netanyahu’s decision to order it.

As a result, these dynamics pretty much rendered obsolete previous talk of a possible Gantz-led minority government that would have to be backed from outside the coalition by some or all of the Arab MKs from the Joint List.

Such talk followed the electoral tie, whereby Likud and its satellites garnered 55 of the Knesset’s 120 seats, while Gantz and his allies, even when counting the non-committal Avigdor Lieberman and secularist right-wing Israel Beitenu party, add up to only 52. The Joint List’s 13 seats might have been the key to balancing this equation for Blue and White – until their response to the fighting in Gaza ended most talk of an Arab-backed coalition.

By the same token, the harmony that the fighting spawned between Likud and Blue and White may well help them find a formula that would allow them to create a broad government.

Coalition talks were deadlocked over three issues when the fighting flared:

Who would be prime minister first in a rotation between Gantz and Netanyahu?

Whether Netanyahu would resign, or just be declared “incapacitated,” if and when he is indicted, as he is expected to be shortly, on corruption-related charges in three separate cases? Another controversy is whether he would be allowed to seek a parliamentary immunity vote in the Knesset if indicted.

Whether four smaller right-wing or religious parties with which Likud had formed a post-election bloc will become part of the unity government?

The Gaza fighting may place these issues in some perspective. The public is both anxious about events in Gaza and angry at the politicians for failing to produce a new government – and a broad coalition may still emerge sometime by Dec. 11, the final legal deadline for the current Knesset to establish a government.

Ironically, one victim of such a development would be newly-appointed Defence Minister Naftali Bennett, who by a strange sequence of events took office the day before Abu al-Ata’s elimination.

A 47-year-old veteran of the elite Sayeret Matkal commando unit – where Netanyahu served a generation before him – Bennett became a millionaire after selling a multi-million dollar data security company he established with some partners before entering politics.

The Modern Orthodox Bennett first led the religious Zionist party Bayit Yehudi (Jewish Home), which at one point won the support of one-tenth of the electorate. Now, however, Bennett heads a minuscule faction of three.

Having long criticised Netanyahu for being, in his view, indecisive in the face of Gaza’s violence, Bennett’s hopes of becoming defence minister were repeatedly dashed, most frustratingly late last year when Netanyahu assumed the office himself following the resignation of Avigdor Lieberman from the position.

Now the appointment he has coveted for so long has materialised just after Bennett’s relegation to the political margins, perhaps reflecting Netanyahu’s fear that Bennett might abandon his orbit and join Gantz.

The operation in Gaza had been prepared months ago, and Bennett’s appointment had no effect on the IDF’s plans. Moreover, Netanyahu’s apparent goal of seeking unofficial arrangements with Hamas that will maintain quiet is anathema to Bennett, who has preached the liquidation of Hamas’ leadership.

Then again, Netanyahu also used to make similarly bellicose statements prior to his return to the premiership last decade. Furthermore, if a unity government emerges, Bennett will have to vacate the defence portfolio a few weeks or months after assuming it.

Yet Bennett is an emphatic supporter of the unity government idea, and says he is ready to give up the defence ministry in order to make it happen.

The outcome of Israel’s ongoing political standoff and Bennett’s place within it remains difficult to predict. What can be safely predicted is that concerning the war on PIJ, everyone outside their Iranian patrons will remain in furious agreement – including not only Netanyahu, Gantz and Bennett, but also the international community, and even Hamas.

Tags: Gaza, Hamas, Israel, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Palestinians