Australia/Israel Review

Bilio File: His Story, Not History

Mar 11, 2021 | Allon Lee

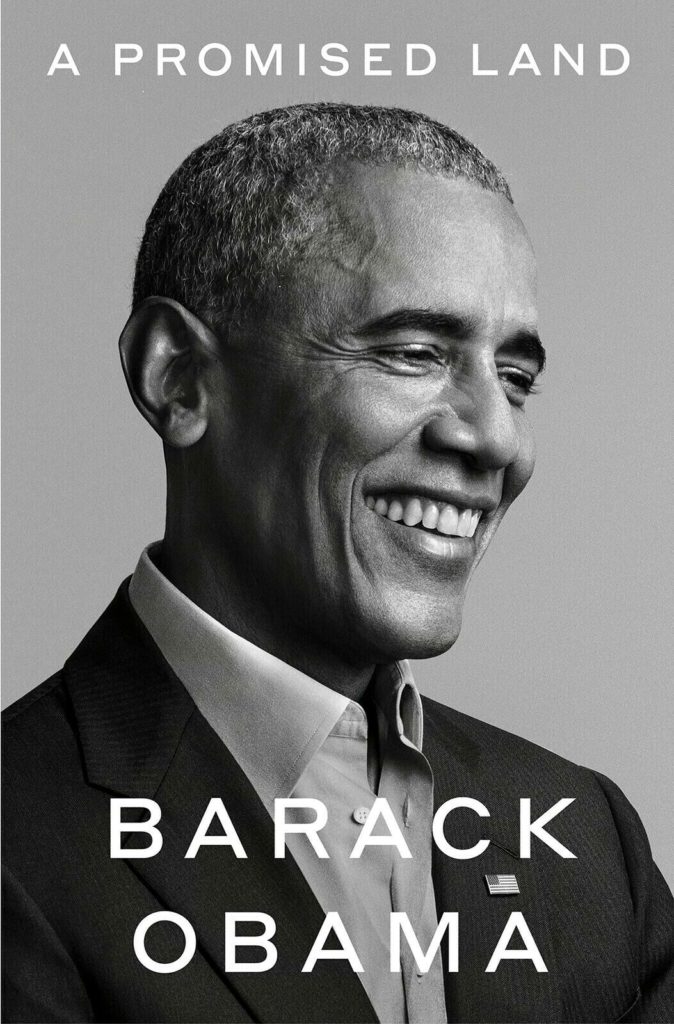

A Promised Land

A Promised Land

Barack Obama, Penguin UK, 2020, 768 pp., RRP $65.00

When volume one of former US President Barack Obama’s two-part presidential memoir dropped in November, there was considerable anticipation over what it might reveal.

His presidency was punctuated by frequent disagreements with current Israeli PM Binyamin Netanyahu over Iran, settlements and peace talks with the Palestinians.

The chapter dealing with the Arab-Israeli issue and the period of 2009-2011 is mostly short on fireworks. Instead, what we get is a slow burn that repeatedly roasts Israel and especially Netanyahu, while only occasionally singeing Arab leaders.

Marred by numerous sins of commission and omission, the chapter’s chief value lies in the direct access it offers into Obama’s thinking.

An unpromising start

Reading the former President’s history of the Arab-Israel conflict, one can infer that, in essence, Obama views Zionism as colonialism.

Obama incorrectly sequences the start of the conflict to the 1917 Balfour Declaration, and incorrectly states that “the British, who were then occupying Palestine, committed to create a ‘national home for the Jewish people.’”

The Balfour Declaration was issued prior to Britain capturing the territory from the Ottoman Empire and was issued only after gaining the support of Britain’s French, American and Italian allies, as historian Martin Kramer has demonstrated.

More problematic still is Obama’s anachronistic terminology about “occupying Palestine”, suggesting a recognised, well defined state.

The reality is that no such state had ever previously existed and it was four years after Balfour before the geographic boundaries were finalised into what is sometimes referred to as “historic Palestine”.

There is a hint of the lawless Wild West in Obama’s account of Jews trying to create a homeland in Palestine over the following 20 years – describing a “surge of Jewish migration into Palestine” and “Zionist leaders… organis[ing]… highly trained armed forces to defend their settlements.”

Obama doesn’t explain how the supposedly “highly trained armed forces” grew up in response to murderous mobs fired up by antisemitic rhetoric perpetrating pogroms and other violence.

The chapter does acknowledge Arab opposition to the 1947 UN Partition Plan which would have created a Palestinian Arab state, but explains it away as due to the Arabs “just emerging from colonial rule.”

Moreover, loath to blame the subsequent violence on rejectionism toward the two-state formula by the Arab side, Obama says “as Britain withdrew, the two sides quickly fell into war.”

Yet the reality is that – following the Arab League’s stated intentions to launch a “war of annihilation” against any Jewish state – a wave of terror against Jewish targets started the day after the Partition Plan passed.

This became a wider conflagration as five neighbouring Arab countries tried to snuff out the nascent Jewish state militarily when it was declared six months later.

In contrast, the mainstream Jewish leadership advocated pragmatism, compromise and for all sides to peaceably implement the two-state formula.

Yet Obama dismisses the moderation of Israel’s leadership as growing out of the barrel of a gun, writing, “with Jewish militias claiming victory in 1948, the State of Israel was officially born.”

It feels somewhat ironic given the book’s title – A Promised Land – that Obama appears to lack understanding and sympathy towards Zionism – the political term Jews use to express their right to self-determination in the land where they became a people.

He also arrogates to the US an oversized responsibility for perpetuating the conflict because it “became Israel’s primary patron – and with that, Israel’s problems with its neighbours became America’s problems as well.”

Except that, until 1967, US support for Israel was almost wholly political and moral, with France meeting Israel’s materiel needs.

Post-1948, Obama takes as a given the myth that Palestinians were denied opportunities or options to improve their situation – ignoring Jordanian and Egyptian occupation of the West Bank and Gaza until 1967, with no moves to create a Palestinian state.

Of the 1967 war he writes, “Palestinians living within the occupied territories, mostly in refugee camps, found themselves governed by the Israel Defense Forces.” [emphasis added]

This is mostly wrong.

In 1961, Life magazine’s Martha Gellhorn visited Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, Gaza and the West Bank, noting that “over half of the registered Palestinian refugees do not live in camps.”

The significance of Arab leaders rejecting the land for peace formula in 1967 also does not appear to have been understood by Obama.

This then is the intellectual suitcase that Obama brought into the White House.

Palestinians – 1, Israel – 0

Entering the White House, Obama sees peace as a strategic value and Israel and especially Netanyahu as the barrier to achieving it.

He says former Palestinian President Yasser Arafat’s “tactics” were “abhorrent” and agrees that “Palestinian leaders had too often missed opportunities for peace,” but makes it clear that he views this as less significant than the fact Palestinians live under Israeli occupation, which, he thinks, is why terror exists.

He writes of the barriers to peace in 2009, that “most important, Israeli attitudes toward peace talks had hardened, in part because peace no longer seemed so crucial to ensuring the country’s safety and prosperity.” [emphasis added].

He says Netanyahu’s “reluctance to enter into peace talks” is “born of Israel’s growing strength” whilst portraying Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas as a man of peace prevented from pursuing it by “political weakness.”

History? What History?

Obama justifies these assertions by effectively sweeping contrary history under the carpet.

In Obama’s account, peace efforts ended when Israeli PM Ariel Sharon and US President George W. Bush assumed office in 2001.

Obama writes, “The Bush administration’s focus on Iraq, Afghanistan, and the War on Terror left it little bandwidth to worry about Middle East peace, and while Bush remained officially supportive of a two-state solution, he was reluctant to press Sharon on the issue.”

Conveniently forgotten is Israeli PM Ariel Sharon’s pivotal withdrawal of all settlers and settlements from Gaza and three areas on the West Bank in 2005, at the end of the Second Intifada.

In return, the Bush Administration assured Sharon of US support for Israel to modify its borders to retain the large settlement blocs under any future peace deal.

Bush’s 2007 Annapolis peace conference – including Israel, the Palestinians, the Arab League, the EU and others – is also ignored, as are then-US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s mediation efforts in 2007/08. Those efforts culminated in then-Israeli PM Ehud Olmert’s offer of a Palestinian state – the most generous offer Israel has made – which Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas rejected, as he himself said, “out of hand”.

Simultaneous with these peace-making efforts, Hamas staged a violent takeover of Gaza in June 2007 that led to thousands of rockets being fired into Israel, culminating in the first Gaza war in December 2008.

None of this was ancient history and none of it involved Netanyahu, who had been out of power.

Neither Israel nor Netanyahu were against “peace talks” based on “Israel’s growing strength”, but were sceptical because of this history. Yet in Obama’s account, it never happened.

Daydreaming about daylight

Convinced that Netanyahu was the main impediment to peace, Obama determined to try a different method to advance peace talks.

He says his first chief-of-staff Rahm Emanuel advised him early on that “you don’t get progress on peace when the American president and the Israeli prime minister come from different political backgrounds.” (This is historically dubious. The breakthrough Israeli-Egyptian peace deal in 1979 was signed with right-wing prime minister Menachem Begin in Jerusalem and centre-left President Jimmy Carter in Washington.)

We know from contemporary media reports in 2009 that Emanuel also counselled Obama to follow a policy of “tough love” with Netanyahu.

The pair settled on a policy of what became colloquially known as “putting daylight” between the US and Israel (although Obama does not explicitly embrace that term).

In fact, this “daylight” policy ran against the grain of all past US experience.

As reported in July 2009, senior mainstream US Jewish leaders told Obama “that the past eight years had demonstrated that the best chance for peace came when there was no daylight between the US and Israeli positions, Obama pushed back, noting that the close ties between the Bush Administration and the governments of Ariel Sharon and Ehud Olmert had in fact produced no significant progress toward peace” (again forgetting Olmert’s unprecedented 2008 offer and the Gaza withdrawal).

According to Michael Oren’s memoir of his stint as Israeli Ambassador to the US, also feeling that such “daylight” ran counter to an understanding of how the US-Israel relationship functions best,was Obama’s own Vice President, Joe Biden.

Israel as carrot and stick

Obama says that he needed to “coax” Netanyahu and Abbas to the negotiating table.

Yet no Israeli leader would refuse a US request to talk peace, and the fact that Obama insisted on “tangible concessions” from Israel to give Abbas “political cover” to enter negotiations proves it was not Netanyahu preventing talks.

Obama says the plan devised to restart talks was to freeze all building in West Bank settlements, and implies his approach was backed by “a talented group of diplomats, starting with Hillary [Clinton], who was well versed on the issues and already had relationships with many of the region’s major players… I appointed former Senate majority leader George Mitchell as my special envoy for Middle East peace.”

But Obama actually appears to have ignored his own handpicked team’s advice. Clinton’s 2014 memoir states that she and Mitchell opposed the policy, fearing that “we could be locking ourselves into a confrontation we didn’t need, that the Israelis would feel they were being asked to do more than the other parties, and that once we raised it publicly Abbas couldn’t start serious negotiations without it.”

Of course, Obama does not mention this opposition, and even today apparently cannot see what Clinton saw in 2009.

He bemoans that people were complaining “we were picking on Israel and focusing on settlements when everyone knew that Palestinian violence was the main impediment to peace.”

Obama is here verballing mainstream American Jewish leaders. Frustrated by the criticism, Obama grumbles that “policy differences” with Israel “exacted a domestic political cost that simply didn’t exist when I dealt with the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Japan, Canada, or any of our other closest allies.”

Obama’s analogy is illogical and offensive. He never asked of those countries anything similar to what he asked of Israel, especially after Israel had taken tangible risks by signing the Oslo Accords and making territorial withdrawals and in exchange had unlocked a Pandora’s box of genocidal threats and record Israeli civilian fatalities.

Moreover, it is hard to take seriously Obama’s claim of a “political cost”, when, as he admits, Jewish voter support at the ballot box remained “more than 70 percent.”

Obama insinuates that hostility to him and his approach to the conflict was due to the power of pro-Israel lobby groups, and perhaps racism.

He also quotes a confidant telling him, “You’re a Black man with a Muslim name who lived in the same neighborhood as Louis Farrakhan and went to Jeremiah Wright’s church.”

But as Obama’s own officials saw, his policy approach was misguided, and the fact that Americans who care about Israel correctly said so had nothing to do with the colour of his skin.

Unholy row

Back to the settlements freeze, which Netanyahu implemented for 10 months.

Here, Obama shows some rare clarity, admitting that “no sooner had Netanyahu announced the temporary freeze than Abbas dismissed it as meaningless, complaining about the exclusion of East Jerusalem.”

Abbas finally agreed to direct talks “just one month before the settlement freeze was set to expire” but “conditioned… participation… on Israel’s willingness to keep the settlement freeze in place – the same freeze he’d spent the previous nine months decrying as useless.”

Yet Obama quickly dismisses Abbas’ dilatory tactics as minor, especially compared to the crisis caused by the “Israeli Interior Ministry announcing permits for the construction of sixteen hundred new housing units in East Jerusalem” just as Vice President Biden paid a “goodwill visit” in March 2010.

Obama dismisses as “fiction” Netanyahu’s claim the timing was a “misunderstanding” – even though Israeli officials involved in the decision confirmed the PM had nothing to do with that timing.

Moreover, the proposed housing was in Ramat Shlomo, a long-established area immediately adjacent to the pre-1967 armistice line which leaked Palestinian documents show Palestinian negotiators had long conceded would remain Israeli in any future peace.

It is widely understood that the Obama Administration seized upon the announcement – which did not violate any Israeli pledge to the US – as a pretext to create a crisis in relations and pressure Netanyahu.

Biden admitted as much in a speech whilst still in Israel, saying he strongly condemned the announcement “at the request of President Obama.”

Lessons not learned

The chapter concludes with Obama chiding Netanyahu, Abbas and other Arab leaders for lacking vision.

Yet instead of drawing appropriate conclusions and realising that maybe the time was not right for major peace initiatives, Obama would return to this challenge in 2013-14, with arguably grievous consequences.

But to hear about those, readers will have to await volume two of Obama’s memoirs, which will also include Obama’s take on his frictions with Netanyahu over Iran’s nuclear program.

Tags: Barack Obama, Israel, Palestinians, United States