Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: The ideology that says Israel’s existence is genocide

Dec 18, 2024 | Julie Szego

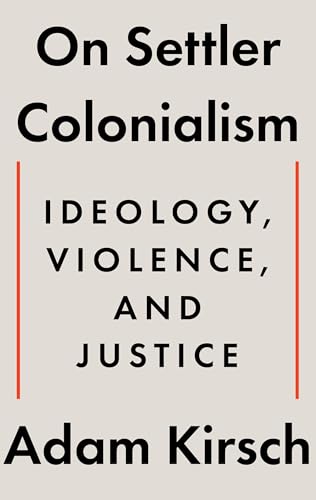

On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice

On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice

Adam Kirsch

W. W. Norton & Company, August 2024, 160 pp, A$41.35

The eruption of anti-Israel bile since the October 7 attacks felt surreal – it still does. Activists demanding Israel be ostracised emerged from seemingly everywhere; from the ABC to Legal Aid to the Department of Defence, for crying out loud. Queers for Palestine – surely this is a joke?

Within days of the massacre, petitioners at Melbourne’s literary Overland journal decried Israel’s “ongoing genocide” and “annihilation” of the Palestinian people.

It wasn’t the display of Israel animus on the political left I found staggering – I’ve documented that pathology in countless newspaper columns during the past 20 years.

No, it was the many disparate causes effectively merging with the Palestinian cause to the point of self-abnegation and the absence of shame in echoing antisemitic tropes about Jewish depravity and deceit.

Something had clearly been seeded while we were sleeping only to burst forth once the conditions were ripe. But what, exactly?

A compelling answer is found in Adam Kirsch’s On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice. Kirsch distills, in a mere 132 pages, the essence of a relatively new ideology that’s all but hijacked the Israel-Palestine debate in anglophone countries, how it took shape within academia, and why we should all be worried about it.

The belief system thrust into the mainstream after October 7 is not exclusively concerned with Israel and the Middle East. Its centre of gravity is rather the US, Canada and especially Australia, countries with shameful episodes in their origin stories.

One of the revealing aspects of settler colonial ideology is the way it conceals itself within a linguistic sleight of hand.

The term “settler colonialism” can be used in a neutral sense to describe historical events. But in academia, the term is an explanation – a denunciation – of Australia and other Western countries today.

Because the term blends historical fact with contemporary mythology, it becomes very challenging to critique – what reprobate individual would argue in favour of settler colonialism given the misery and intergenerational trauma that European colonialists visited on indigenous peoples?

While Kirsch writes principally for an American audience, we learn early on that settler colonialism is something of an Australian export.

The term “settler colonialism” was first coined by an Australian scholar abroad; Kenneth Good, a political scientist who taught briefly at the University of Rhodesia in the 1970s. Good described as “settler colonial” places such as Rhodesia and Algeria where a sizeable number of Europeans had enjoyed dominance over the local population.

But in Kirsch’s telling, this story really starts in the 1990s when the idea of “settler colonialism” underwent a crucial shift – in Australia. At the time, the nation was grappling with what became known as “the history wars”, a debate about how to evaluate Australia’s colonial past.

It was then that theorists began referring to Australia as a “settler colonial” entity. In a seminal 1999 text, anthropologist Patrick Wolfe wrote what would become the most frequently quoted sentence in the history of this new academic discipline: “The colonisers came to stay – invasion is a structure, not an event.”

And thus, “settler colonialism” was born not as a descriptor of tragic historical events but as an ideology that proposes what Kirsch calls a “new syllogism”. That is: if settlement is a genocidal invasion, and invasion is an ongoing structure and not a completed event, “then everything and everyone that sustains a settler colonial society today is also genocidal.”

The spiritual evil driving this genocide is defined as European “insatiability”: a lust for resources, for power and even for knowledge.

This European rapaciousness – in the lingo, “settler ways of being” which is contrasted with the idealised “indigenous ways of knowing” – underlies all our norms and institutions, including national borders, Western science and the heterosexual nuclear family. (Perhaps you’re starting to glimpse the ideological scaffolding behind “Queers for Palestine”?)

The guiding premise of settler colonial ideology is that European settlement should never have happened, so it follows that the only real way to make amends would be to rewind time and revert to indigenous sovereignty – which is impossible. We can only devote ourselves to the never-ending “work” of decolonisation.

Kirsch exquisitely documents how Lorenzo Veracini, a leading theorist from Melbourne’s Swinburne University, pondered what doing “the work” of decolonisation might mean in an Australian context. Back in the 1960s, Frantz Fanon, part of the leadership of Algeria’s brutal FLN, and author of the seminal text, The Wretched of the Earth, defined “the work” as bringing about the (literal) “death of the colonist.”

“‘I recommend a Fanonian (and metaphorical) cull of the settler’, Veracini writes – conscious,” Kirsch notes, “that the two adjectives pull in opposite directions.”

And so, understanding their calls for murder can only be metaphorical, the scholars of settler colonialism indulge in conspiratorial thinking and rhetorical violence.

Ah, but what, Kirsch asks in a masterful pivot, if there were a country where settler colonialism could be challenged with more than just words? A country, as it happens, whose people Western civilisation has traditionally considered it virtuous to hate?

And so we have a concept first developed to explain the history of Australia now most often invoked in connection with Israel. In Palestine, the fable goes, just as in Australia, the European colonisers – which is how the early Zionists are referred to – saw not a land inhabited by indigenous people since time immemorial but “terra nullius”, empty territory.

The Israel-Palestine conflict, Kirsch explains, functions as “the reference point for every type of social wrong,” whether the building of a pipeline under a Sioux reservation or the Mexican experience in the US in the 19th century, which activists duly refer to as a “nakba”.

And with Israel as its centre, settler colonialism throws up what Kirsch identifies as yet another syllogism: “If Israel is a settler colonial state and settler colonialism entails genocide then it is ideologically necessary for Israel to be committing genocide.”

The key point here is that the ideology of settler colonialism defined Israel as essentially genocidal long before the 2023 Gaza war, “creating a frame” through which all of its subsequent actions were viewed. Hence, the Overland petition’s October 2023 reference to Israel’s “ongoing genocide” against Palestinians.

Here, Kirsch explains, the discipline finds itself “having to define genocide down so that it no longer means what it is ordinarily taken to mean.” Once again, Australian scholars come to the rescue: Wolfe devises a category of “structural genocide”, in which even indigenous citizenship in a settler colonial state can be part of the “logic of elimination”.

To make Israel fit the mould of a genocidal settler-colonial regime entails an exercise in disavowal so vast that I don’t have the space to plumb it here – but little of it will be news to regular readers of this publication.

The most revealing passages are where Kirsch traces what we might call settler colonialism’s own repressed unconscious – the age-old antisemitic echoes inherent in defining Zionists and Israelis as emblematic of settler rapaciousness and greed.

We hear over and over that until Palestine is “free” no one is free; eliminating the Jewish state is in this worldview the key to eliminating every injustice in the world – including homelessness in Toronto – wiping the slate clean, returning us all to an innocence before the Fall.

With history falsified to dehumanise Israelis, it was no surprise that so many in the academic world found justifications for the slaughter of October 7 – when they weren’t voicing outright jubilation. After all, these “settlers” had no right to be there in the first place.

As to what “decolonisation” in Israel-Palestine might look like, given that, unlike Algeria in the 1960s, Israeli Jews have no equivalent of France to go back to – not that that stopped a protestor outside Columbia University taunting Jews with “Go back to Poland!” – is never really elucidated.

While Kirsch flags early on his belief in a two-state solution, he leaves a key concession to the end: to Palestinians, Israel does resemble a colonial power because the state was established without the consent of the people already living there. The creation of the Jewish state brought Palestinians displacement and suffering. But conquest and displacement are constants throughout history, which, no matter what Wolfe says, is nothing if not a series of events. Colonisation and the Mabo judgement; the Nakba and the Camp David negotiations: all are events. A progressive movement worthy of its name must acknowledge the bloodshed and injustice of the past while ensuring these do not lay the foundation for even greater bloodshed and injustice in the future.

I have no idea how we pull ourselves out of this new Dark Age to intellectual sanity, but Kirsch offers a place from which the journey can start.

Julie Szego is a Melbourne-based author, lecturer and journalist, who previously wrote for the Age newspaper for more than 12 years and now publishes a Substack newsletter called “Szego Unplugged”.

Tags: Anti-Zionism, Australia, Israel, Media/ Academia, Palestinians

RELATED ARTICLES

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio