Australia/Israel Review

After Bondi

Dec 19, 2025 | Colin Rubenstein

The murderous attack unleashed on the Chanukah by the Sea celebration at Sydney’s iconic Bondi Beach on December 14 was the worst act of terrorism ever perpetrated on Australian soil, eclipsing infamous incidents such as the Sydney Hilton Hotel bombing in 1978 and the Lindt Café siege in Sydney in 2014. It was also the deadliest attack targeting Jews anywhere in the world since Hamas’ infamous pogrom on October 7, 2023.

Furthermore, it will also likely be remembered as the single most significant event in the history of Australia’s tight-knit Jewish community.

Everyone in our community will have been directly affected. Among AIJAC’s small staff, one individual was injured in the attacks – incoming Sydney office head Arsen Ostrovsky – while another staff member lost a cousin among the 15 dead.

And as a result of Bondi, the nature of our community will inevitably change irredeemably.

Our previously largely confident, joyful and optimistic nature – already under pressure over the last two years of escalating antisemitism, doxxing, boycotts, arson and graffiti attacks, harassment and violence – is now even further threatened. It would not be completely inappropriate to suggest that Bondi on December 14 represented the Australian Jewish community’s “October 7”.

The Australian Jewish community is resilient and courageous – but what happened at Bondi, combined with other recent events, will inevitably call into question for some whether an openly Jewish life in Australia will even remain viable in the future.

Our synagogues, schools and other communal institutions already need to be kept under fortress-like security, including, frequently, armed guards.

And still we have had numerous attacks on synagogues over the past two years, including, most infamously, the destruction of the Adass Israel Synagogue in Melbourne last year, as well as the targeting of restaurants, a childcare centre and schools.

Now, after Bondi – targeted, planned mass murder of Jews at one of Australia’s most iconic public places – the question must inevitably be asked: Is it safe for us to ever again have a Jewish communal gathering in any open air public space, no matter what security is put in place?

And then there is the lack of safe access for anyone visibly Jewish to most city centres in Australia on weekends over the past two years. Many of us, quite reasonably, felt it was simply unsafe to be in the vicinity of the hostile, volatile crowds there every week chanting slogans like “Globalise the Intifada”, or “All Zionists are terrorists.” And law enforcement officers appear to agree, frequently telling Jews to “move on” for their own safety when seen in the proximity of these demonstrations.

This is actually a trend that started already with the infamous Sydney Opera House “f-ck the Jews” demonstration on Oct. 9, 2023. The Opera House was illuminated to honour the largely Jewish victims of October 7 – but Jews were not welcome in the area. The antisemitic protesters – who of course were never prosecuted – were allowed by police to take over the streets of Sydney and effectively create a Jew-free zone.

This pattern of police restricting Jews to “protect them” and “keep the peace” has continued, as has the glaring lack of legal action. Blatantly antisemitic sermons by some clerics – including Wisam Haddad, the purported spiritual teacher of Bondi shooter Naveed Akram – were not prosecuted. Haddad only had to face court because Jewish groups brought a civil case against him. In recent court cases, individuals who have attacked synagogues, including the East Melbourne Synagogue arsonist and one of those responsible for the Adass Israel Synagogue firebombing, have been treated all too leniently by our judicial system.

Australian Jews have been proud contributors to this country from its earliest days, and overwhelmingly have great love and gratitude for it. But today, our reality appears to be: we cannot rely on being safe in our communal institutions, even under extremely tight security arrangements; we cannot hold outdoor communal events; we often cannot openly walk the streets of our cities in safety; and we cannot rely on either the police or the judiciary to change these realities. Given all this, frankly, the viability of open Australian Jewish life here looks somewhat precarious.

That is why it is desperately important that Bondi must represent the beginning of a transformational watershed in Australia’s approach to the scourge of antisemitism that has plagued our country for more than two years. If it does not, this must raise very serious concerns about the future of Australia as a tolerant, multicultural liberal democracy, as well as of our own community.

Our political leaders, including the Prime Minister, have all been making appropriately strong statements in the wake of the Bondi tragedy, and for this we are grateful. But now they must do what is necessary to preserve the vibrant, harmonious Australian society we love and celebrate.

This does not mean simply providing more money for security for Jewish institutions to seal themselves off from the murderous hatred that is bubbling away in parts of Australian society – nurtured and encouraged by the pathological and obsessive delegitimisation and demonisation of Israel and “Zionists” that has dominated much of our civil society. Instead, we need leadership and action designed to stop the murderous hatred from growing even further.

Let’s remember that it took until four days after the massacre for the Federal Government to issue even a partial response to the recommendations of its own Antisemitism Envoy, delivered back in July. State governments have made commitments related to new laws to control the ugly protests and then delayed implementing them or ended up watering them down.

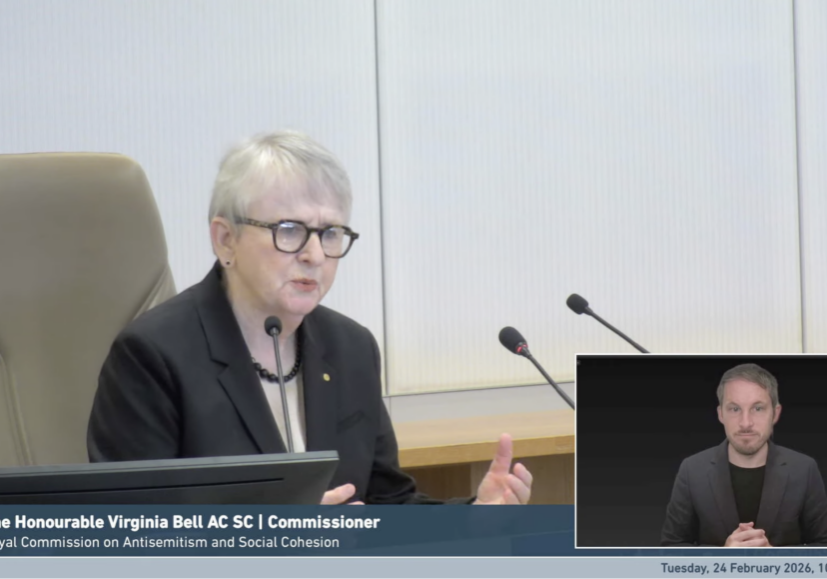

The Antisemitism Envoy’s recommendations must now be fully implemented. Relevant state and federal laws must now be urgently tightened. Police must end their “keep the peace” approach, which allowed the haters to control the streets. But that should just be the start. For instance, a royal commission into Australia’s antisemitism crisis seems amply justified.

Like the rest of the Australian Jewish community, we are still processing the horror of what happened at Bondi – mourning the dead, trying to support the survivors, attempting to participate in picking up the pieces of our shattered communal life. But we do already know that things can never be the same for our community. And we also know that if we do not see a much more serious and urgent approach to the national antisemitism crisis from our governments, law enforcement and civil society bodies, it is overwhelmingly likely that the forces that culminated in Bondi will get even worse – placing Australia’s open, democratic and tolerant society at great risk.