Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Paradigm Shift

Apr 1, 2015 | Evelyn Gordon

Evelyn Gordon

Nowadays, it’s become virtually accepted wisdom that Israel is becoming increasingly right-wing, and that this shift constitutes a major obstacle to peace. No less a figure than Bill Clinton made this claim at a Clinton Global Initiative conference in 2010. A 2011 study by the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies similarly declared, “Today Israel’s Jewish population is more nationalistic, religiously conservative, and hawkish on foreign policy and security affairs than that of even a generation ago, and it would be unrecognisable to Israel’s founders.” A popular corollary of this thesis is that Israel, as it moves rightward, is becoming less democratic, less respectful of civil rights, and less tolerant of minorities.

Both halves of this thesis are wrong. In fact, Israeli politics have shifted sharply to the left; ideas once confined to the far-left fringe are now mainstream. And civil rights, democracy and treatment of minorities have all been improving.

The new pro-two-state consensus

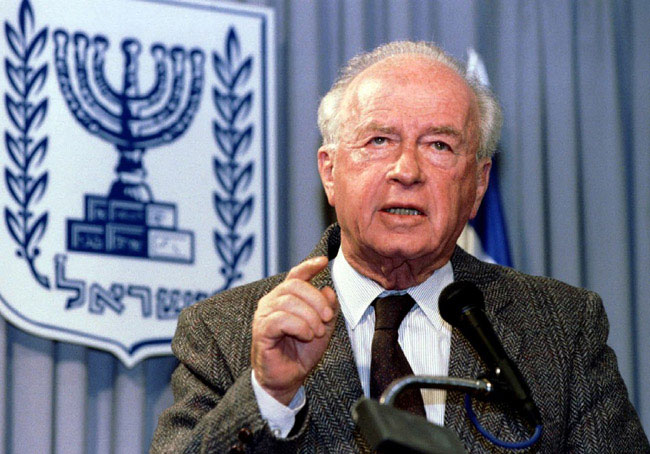

Twenty-two years ago, no one outside the far-left in Israel supported negotiating with the Palestine Liberation Organisation or creating a Palestinian state. The mainstream left, represented by the Labor Party, certainly didn’t; when then-party leader Yitzhak Rabin was elected prime minister in 1992, he campaigned explicitly on promises of no negotiations with the PLO and no Palestinian state. When Rabin violated that pledge by signing the Oslo Accord with the PLO in 1993, the move was hugely controversial, splitting Israel down the middle.

Since then, Israel has experienced 21 years of failed negotiations, in which Palestinians rejected repeated offers of statehood without even making a counteroffer. It’s experienced a terrorist war, the second intifada, which produced more Israeli casualties in four years than all the terrorism of the previous 53 years combined. It’s evacuated every inch of Gaza and gotten some 15,000 rockets in return. It wouldn’t be surprising if Israeli support for Palestinian statehood had declined. Instead, it’s increased. For years now, polls have consistently shown about 60 to 65% of Israelis supporting a Palestinian state.

Even Israel’s main centre-right party, Likud, now publicly backs Palestinian statehood. Likud chairman and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu announced this about-face in a 2009 speech at Bar-Ilan University and has repeated it many times since. This would be noteworthy even if Netanyahu didn’t really mean it. For the fact of the matter is that the leader of Israel’s centre-right publicly declared support for Palestinian statehood, and far from being ousted by an indignant centre-right public, he has been twice re-elected by his own party.

In moments of honesty, even leftists acknowledge the significance of this development. As Geneva Initiative director Gadi Baltiansky, whose organisation has been promoting a draft two-state agreement since 2003, said in September: “It’s true that the public wants a right-wing leader to implement the left’s policies, but it’s also true that the ideological map has moved left.”

All the prime ministers who followed Rabin actually moved far to the left of the vision he outlined in his final Knesset address in October 1995. For instance, Rabin envisioned Israel living alongside a “Palestinian entity… which is less than a state,” and in fact, neither of the two agreements he signed with the PLO mentions a Palestinian state. Yet today, even Netanyahu openly advocates such a state.

Rabin also declared that Israel’s final borders “will be beyond the lines which existed before the Six-Day War” of 1967, specifying in particular that Israel’s “security border… will be located in the Jordan Valley, in the broadest meaning of that term.” But according to both the New Republic and the left-wing Israeli daily Haaretz, even Netanyahu agreed last year to negotiate on the basis of the 1967 lines.

Rabin envisioned a “united Jerusalem, which will include both Ma’ale Adumim and Givat Ze’ev, as the capital of Israel, under Israeli sovereignty.” Since Ma’ale Adumim and Givat Ze’ev are major West Bank settlements located respectively east and north of Jerusalem, this would mean a Jerusalem vastly larger than Israel’s current capital. Yet since then, two Israeli premiers – Ehud Olmert and Ehud Barak – have offered the Palestinians most of east Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount.

Rabin vowed to retain the Gush Katif settlement bloc in Gaza, but since then, Israel has withdrawn from every inch of Gaza. Rabin also pledged “not to uproot a single settlement in the framework of the interim agreement, and not to hinder building for natural growth.” Since then, Israel has uprooted 25 settlements without a final-status agreement (21 in Gaza and four in the West Bank). And in 2009, the “hardline” Netanyahu instituted Israel’s first-ever moratorium on settlement construction, a 10-month freeze that then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton correctly termed “unprecedented.”

In short, not only has public opinion shifted to the left, but so have government policies, on both interim and final-status issues.

If so, why do many people nevertheless think that Israel has moved to the right? Presumably due to one seemingly anomalous fact: a change in how Israelis identify themselves. According to the Peace Index, a regular poll begun in 1994, only 12% of Israeli Jews self-identified as being on the left this past August, while 62% self-identified as being on the right – a dramatic change from the roughly even split of 20 years ago. This change was reflected in the last two Knesset elections, which gave a majority of seats to parties that self-identify as rightist or religious.

But this is misleading; because of the leftward shift of the past 20 years, the term “right” no longer means what it used to. Once, the right opposed any territorial concessions. Today, the right’s acknowledged leader, Netanyahu, publicly supports a Palestinian state. Many Israelis, therefore, now see no contradiction between supporting a two-state solution and self-identifying as “right”.

There is, moreover, one issue on which Israelis really have moved rightward: Due to the combination of two decades’ worth of failed negotiations, the massive upsurge in terror that followed the Oslo Accords, and the almost daily rocket barrages that followed the 2005 pullout from Gaza, polls have shown for years now that despite continuing to support a two-state solution, about 70% of Israelis no longer believe it’s achievable anytime soon.

But that doesn’t change the fact that today’s “right-wing” Israel is a country where the majority hold political positions found only among Hadash, the Arab-Jewish Communist party, two and a half decades ago.

The False Democracy Deficit

The second half of the equation – that Israel is becoming more and more undemocratic and dismissive of human rights – is no less false. But before examining some of the ways in which democracy and human rights have expanded in recent years, it’s important to understand four reasons this canard has become so pervasive.

First, both sides in Israel’s political debate have a bad habit of trying to paint any idea they oppose as fundamentally illegitimate. When rightists dislike an idea, for instance, they call it “anti-Jewish” or “anti-Zionist.” When leftists dislike an idea, they call it “anti-democratic” or “anti-human rights.” But that doesn’t mean it actually is.

Take, for instance, several bills in recent years aimed at giving the public’s elected representatives control over Supreme Court appointments, which leftists have consistently slammed as “anti-democratic.” Former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak, for example, declared that this would “set Israeli democracy back several years” and even “turn Israel into a Third World country.” Yet in almost every other democracy worldwide, Supreme Court appointments are controlled by the executive and/or legislative branches. Only in Israel are justices instead chosen primarily by unelected legal officials. (Israel’s nine-member Judicial Appointments Committee includes three sitting justices chosen by the Supreme Court itself and two lawyers chosen by the Bar Association.) And to claim that appointing justices the same way as all other democracies do would somehow be “anti-democratic” is absurd.

Or consider the firestorm that erupted when the Ministry of Education decided in 2011 that Jewish kindergartens should open the week by singing the national anthem, Hatikva. (Arab kindergartens were exempted lest they find this offensive.) A University of Haifa professor declared that members of the ruling Likud party were competing “to see who can push us faster into the arms of fascism.” A lecturer at a leading teacher’s college termed the directive “reminiscent of education in a totalitarian society.” Yet the decision was essentially no different to America’s practice of having public-school students open the day by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance.

Perhaps the epitome of hypocrisy occurred over several recent bills to declare Israel the nation-state of the Jewish people. The outcry was led by former Justice Minister Tzipi Livni, who described her opponents as “dangerous, extremist parties that must be prevented from taking over and destroying the country.” Yet the most “extreme” version of the bill was a word-for-word copy of one that had been submitted by her own party, with her backing, in the previous Knesset.

A second reason for the canard relates to the nature of democracy itself: Anyone with an idea, however stupid or evil, is free to tout it and even try to enact it, and some of those people even get elected to public office. In any democracy, objectionable proposals periodically arise, and Israel is hardly unique in that regard: Consider last year’s proposal by the mayor of Borgaro, Italy, to run separate bus lines for Gypsies and other town residents. What distinguishes a properly functioning democracy is the existence of self-correcting mechanisms that keep such ideas from being implemented.

So when private members’ bills seeking to deprive political nongovernmental organisations of foreign funding were submitted a few years ago, Israel’s own self-correcting democratic mechanisms solved the problem: Newspapers, civil-society groups, and other Knesset members vociferously objected, and the bills were iced. The same happened when it emerged, a few years ago, that certain bus lines serving ultra-Orthodox communities were making women sit at the back of the bus. Israel’s own democratic mechanisms soon got the practice stopped.

The problem is that such issues generally get massive media play when they first arise, and then very little once they are resolved.

A third crucial factor is that news from Israel is invariably reported devoid of comparative context. Take, for instance, the wave of vandalistic attacks on mosques in recent years that is frequently cited as proof of Israeli “racism”. Such attacks are clearly abhorrent. But they are actually far less common in Israel than in many other Western democracies. During Israel’s worst years for such attacks, 2009-2014, Wikipedia lists a grand total of 24. By comparison, after a Muslim extremist assassinated filmmaker Theo Van Gogh in Holland, researcher Ineke van der Valk counted 117 “incidents” at Dutch mosques in 2005-2010, including graffiti attacks, vandalism, arson, and more. So Holland, whose population is twice that of Israel, had almost five times as many mosque attacks over a comparable time period.

Another factoid cited to demonstrate a worsening problem in Israel’s treatment of non-Jews is the country’s infant-mortality rate. In 2011, it was 2.6 per 1,000 for Jews and 6.8 for Muslims, a gap of 4.2 births per 1,000. In isolation, that may sound like proof of shocking discrimination. Yet in Britain that same year, the majority-minority gap was significantly larger, at 4.8 births per 1,000 (3.7 for whites and 8.5 for those of Pakistani origin). And in neither country is the gap due solely, or even primarily, to discrimination. For instance, consanguineous marriages, which produce more fatal birth defects, are more common among Muslims than non-Muslims; additionally, infant mortality rates are higher among teenage mothers, and teenage mothers are more common in the Muslim community.

And that is the final factor behind the anti-Israel canard: As with infant mortality, differential outcomes don’t automatically indicate discrimination. They often stem at least partly from cultural differences. For instance, a study by Israeli-Arab researcher Dr. Rafik Haj found that Israeli-Arab towns have less money to spend on services than do equivalent Jewish towns in part because they collect taxes from only 27% of residents, while Jewish towns at the same socioeconomic level collect taxes from 63% of residents.

Similarly, the fact that no Arab party has ever served in a governing coalition doesn’t mean that Arabs per se are “excluded” from government; indeed, there have been several Arab ministers and deputy ministers from non-Arab parties. What excludes the Arab parties is their political positions, such as their consistent opposition to any and all counter-terrorism operations. Since all non-Arab parties view counter-terrorism as a core government responsibility, this essentially precludes their sitting in a coalition together.

Looking at the Trendlines

In short, when evaluating news from Israel that sounds racist, anti-democratic, or discriminatory, four tests should always be applied: Is the “objectionable” proposal actually standard democratic practice? Have Israel’s own democratic mechanisms solved the problem? How does Israel compare with other Western countries on this issue? And to what degree is the problem due to factors that have nothing to do with discrimination?

But since no country in the world has yet figured out how to eradicate racism, discrimination or gaps between population groups, there’s one final question that must also be asked: Are things getting better or worse? In Israel, the answer is that they’re getting better.

To appreciate the magnitude of the progress in Israel, one must understand that the pre-1967 “golden age”, for which liberal Jews often seem so nostalgic, was actually far from golden for many people. Anyone who belonged to the wrong political party (Menachem Begin’s Herut rather than the ruling Mapai) was systematically excluded not only from government, but also from the workplace: Much of the economy back then was state-owned, and state-owned companies wouldn’t hire anyone who couldn’t prove membership in the Histadrut, the labor union affiliated with Mapai. Jews of Middle Eastern origin, known in Israel as Mizrahim, were systematically excluded from the higher ranks of government, academia, state-owned companies, and any other institution affiliated with the state, all of which were dominated by Ashkenazi Jews. And Israeli Arabs weren’t just excluded; they were under military government until 1966.

All that has since begun to change, especially over the past two decades. A study conducted by Momi Dahan in 2013 found that while the anti-Mizrahi discrimination of those early decades hasn’t been eliminated, the gaps have narrowed significantly. In 2011, the average Mizrahi household still earned 27% less than the average Ashkenazi one – but that’s down from 40% in 1995, a relatively steep decline in just 16 years. And among the economy’s top 10%, Mizrahim are now represented proportionally to their share of the total population.

Mizrahim are also now routinely represented in the highest ranks of government and government institutions; they have served as senior cabinet ministers, Supreme Court justices, an IDF Chief of Staff, and more. In short, Israel has moved steadily from excluding half the Jewish population toward including it.

Women, too, have made notable progress. They still earn less per hour than men, but according to a 2014 study by the Knesset Research Centre, the pay gap is identical to the European Union average. And while women remain underrepresented in many institutions, their representation has grown steadily. For instance, the Supreme Court got its first woman president only in 2006, but its second took office in January.

Perhaps most noteworthy, however, has been the progress toward integrating Israeli Arabs. In terms of the letter of the law, Israel’s treatment of minorities has long compared favourably with Europe’s. To cite a few salient examples, Israel doesn’t have a law banning minarets, as Switzerland does, or a law barring civil servants from wearing headscarves, as France does; nor does it deny citizenship to Arabs just because they can’t speak the majority’s language, as Latvia does to some 300,000 ethnic Russians born and bred there. But over the past two decades, successive Israeli governments have invested heavily in trying to create de facto as well as de jure equality. And while the job is far from done, the improvement has been impressive.

For instance, in 1996, according to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics, only 23.7% of Arabs obtained a high-school matriculation certificate that met university entrance requirements, compared with 42.4% of Jews. By 2012, the gap had shrunk by a third even though the Jewish rate rose to 51.0%, because the Arab rate had risen even faster, to 38.2%. And while the improvement has encompassed the entire Arab community, it’s been particularly steep in places where local governments have made education a priority. The Druze towns of Isfiya and Yarka, for instance, boosted their matriculation rates by about 20 percentage points just from 2012 to 2013, while the impoverished Druze town of Beit Jann now has the second highest matriculation rate in Israel. As Haaretz reported in 2013, moreover, heavy investment in the construction of Arab schools has brought average class sizes in these schools down to 28.5 students, identical to the nonreligious Jewish state schools.

In higher education, Arab progress has also been significant. In 2005, according to the statistics bureau, only 4.2% of all master’s degrees were awarded to Arabs. In 2013, the figure was 8.6% – meaning it more than doubled in just eight years. During those same eight years, the proportion of PhDs awarded to Arabs rose by 40%, from 2.5% to 3.9%. Clearly, these figures are still too low, given that Arabs constitute 13% of the workforce and 20% of the population, but the Jewish-Arab gap is steadily narrowing.

The number of Arabs working in high-tech almost sextupled from 2009 to 2014, according to a Bloomberg report in November; the boost came partly from a government program that, as Haaretz reported, subsidises starting salaries for Arab high-tech workers by up to 40%. And at Israel’s premier technology university, the Technion, Arab undergraduates now constitute 21% of the student body – slightly higher than their share in the population – thanks to a special program to recruit them and then give them extra support to keep them from dropping out.

Arab and Jewish consumption patterns, moreover – a good indication of living standards – have converged, as the online journal Mida reported in November. Average outlays per family in urban Arab localities are lower than in wealthy Jewish cities such as Tel Aviv, but higher than in other Jewish-majority cities such as Haifa or Ashdod. And on a few issues, Arabs actually surpass the Jewish population: For instance, 93% of Arab households own their own home, compared with 70% of Jewish households.

Ron Gerlitz, co-executive director of the Jewish-Arab organisation Sikkuy (the Association for the Advancement of Civic Equality), summed up the dramatic advances in integration in a Haaretz column in August 2014. “In the past,” Gerlitz wrote, “if Israeli Jews did not go to Arab communities, they never saw Arabs, except for laborers. But now, if they go to a pharmacy they are likely to be served by an Arab pharmacist… If they go to the emergency room, they are likely to be treated by an Arab doctor… Jewish college students in Israel often have Arab lecturers. There are Arab department heads and even one Arab college president. Former President Moshe Katsav was convicted of sex crimes and sent to prison by a panel of judges headed by an Arab.”

None of this means that discrimination doesn’t still exist; it does. But significant efforts have been made, and are being made, to reduce the gaps, and these efforts are working.

Nor, contrary to the accepted wisdom, is anti-Arab prejudice on the rise, according to Professor Sammy Smooha, of Haifa University, who has been tracking anti-Arab prejudice since 2003. “The data don’t support the view that there has been an ongoing radicalisation of Jewish attitudes toward Arabs,” he wrote in the annual report he published last May. “In fact, they indicate stability in Jewish attitudes over the last decade.”

Smooha noted, moreover, that this stability was maintained even though Arab attitudes toward Jews and Israel really did become more extreme between 2003 to 2012, though the trend reversed slightly in 2013. And in some respects – such as the proportion of Jews who say they would be comfortable having Arab neighbours – Jewish prejudice has declined markedly in the past decade.

If Smooha’s conclusion sounds counterintuitive, the culprit might well be social media. Vile statements abound on both Jewish and Arab social networks, and while such sentiments always have existed, they used to be kept decently private. Now they’re out in the open for everyone to see, which creates the perception that racism has become more prevalent even though the data do not support it.

Smooha’s finding that Arab attitudes truly have radicalised over the past decade also merits more attention than it usually gets. It’s an unavoidable fact that Palestinians have been at war with Israel since its inception, and many Israeli Arabs – including all their elected representatives – vocally side with the Palestinians in this war. Under these circumstances, it’s fantasy to think that all prejudice can be extirpated; the Palestinian-Israeli conflict creates a real source of mutual suspicion that can’t simply be waved away.

But by comparison with other countries in similar circumstances, Israel has done remarkably well. Not only has it consistently upheld Arab political and civil rights for decades – Freedom House awards it a top-flight ranking of 1 out of 7 for political rights and 2 for civil rights – but it has also managed to steadily increase Arab opportunities and integration and make most of its Arab citizens feel that despite the problems, Israel remains a good place to live. Indeed, an Israel Democracy Institute survey conducted last May found that 65% of Israeli Arabs were “quite” or “very” proud to be Israeli, while 64% said they usually felt their “dignity as a human being is respected” in Israel.

The irony, as Gerlitz noted in his Haaretz article, is that this growing integration might actually be exacerbating Jewish-Arab friction. He blamed this on a backlash from Jewish extremists, but the truth is that increased integration among any two population groups often initially exacerbates tensions, as people who previously had little to do with each other suddenly have to learn to live and work side by side. That happens everywhere, even in countries where the situation isn’t complicated by an ongoing war in which many members of the minority vocally identify with the enemy.

The very fact that Arab integration is advancing rapidly in some ways makes the situation in Israel now particularly flammable, and it clearly isn’t helped by the fact that certain parliamentarians, both Jewish and Arab, have been doing their best to fan the flames. Nevertheless, the kind of problems that stem from growing integration are infinitely preferable to the alternative – because ultimately, they bode much better for Israel’s future.

Evelyn Gordon is a veteran journalist and commentator living in Israel. © Commentary (www.commentarymagazine.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel