Australia/Israel Review

Bibi Comes Back

Apr 1, 2015 | Amotz Asa-El

Amotz Asa-El

In an electoral upset on par with Attlee’s defeat of Churchill in 1945 and Truman’s of Dewey in 1948, Binyamin Netanyahu emerged from Israel’s twentieth general election with a decisive victory that has left pundits, pollsters and rivals dumbfounded.

The pollsters were mistaken twice. Before the election they reported a gradually growing advantage for opposition leader Isaac Herzog’s Zionist Union, which by the last weekend before the 17 March election stood at approximately 25 to the Likud’s 21 of the Knesset’s 120 seats. Then, when the voting had ended and three Israeli TV channels reported the results of their exit polls, they said Herzog and Netanyahu were tied at 27 apiece.

Those were the figures with which many went to sleep Tuesday midnight, including Herzog himself, only to wake up Wednesday morning and learn that the real result was 30:24. Netanyahu’s Likud and other parties that would be natural coalition allies to it would send 67 lawmakers to the legislature, controlling 56% of the Knesset.

The polling debacle is attributed to two factors: first, voters who remained undecided until voting day, and second, the fact that exit polling ended two hours before the real voting, with late Likud voters apparently flocking to the ballots in droves in those final hours. While polling experts will continue to explore this cryptic aspect of the election, the vote’s political meaning is crystal clear.

Twenty-six years after becoming a lawmaker and 19 after first winning the premiership, Netanyahu not only proved his eulogies premature, but has reached a new biographical peak to his illustrious career.

On the eve of his fourth premiership, Netanyahu’s leadership appears threatened by no one, whether within his party, elsewhere on the right, or in the opposition. If he completes the four-year term for which he has just been elected, he will have been prime minister for 13 years, a feat equalled only by the Jewish state’s founding leader, David Ben-Gurion.

The causes of Netanyahu’s surprise victory and his rivals’ defeat range from the circumstantial to the substantive.

On the circumstantial level, pundits agree Herzog’s decision to rotate the premiership with his ally, former Justice Minister Tzipi Livni, struck many swing voters as an administratively bizarre and politically alarming show of weakness. Evidently, Livni accepted this criticism when she said the day before the election that she will not insist on the deal’s execution “should this be the obstacle to assembling a coalition.”

Within Herzog’s party, many also criticised their campaign as unfocused, lacklustre and disorganised, as a deep sense of defeat descended on the party despite its rise from 15 to 24 seats, the addition coming in large part from Livni’s constituency, which in the last election comprised six Knesset seats.

Outside the losing camp, critics now say that swing voters were taken aback by what they saw as a character-assassination campaign against Netanyahu and his wife, Sara, and by reports that various anti-Netanyahu campaigns enjoyed foreign funding.

At the same time, many in Labor attribute their defeat to Netanyahu’s interviews in the last days before the election, which they labelled as fear-mongering and incitement. By warning of a foreign-fuelled effort to raise Arab Israeli turnout, and by amplifying a famous artist’s broadside in a Labor rally that Likud’s voters are idol worshippers, Netanyahu pushed to the ballots a lower-class electorate that would otherwise not have bothered voting, they say.

On the more substantive level, pundits agree that many felt Netanyahu was being unfairly besieged by foreign governments, and that many voters were persuaded by his mantra that Labor’s leaders are too weak to handle the challenges Israel faces, from Teheran to Gaza.

Having said that, the victory was not a landslide, and it was not won thanks to any traffic between right and left, but by rearrangements within the right and left, and in the centre that sprawls between them.

Netanyahu took a huge gamble when he called an early election last fall. Israeli voters had repeatedly punished politicians who called early elections, most memorably Yitzhak Rabin in 1977, when Labor first lost power, and Shimon Peres in 1996, when the Nobel Peace Laureate was stunned by a 47-year-old Netanyahu. This time, however, the early-election gamble worked. Netanyahu not only won, he achieved his gamble’s strategic aim – to replace his coalition partners.

In the coalition Netanyahu dissolved in December, he shared space with then Finance Minister Yair Lapid’s sizeable and contrarian Yesh Atid (“There is a Future”) faction, which by last winter had almost as many seats as Netanyahu’s truncated Likud, following Avigdor Lieberman’s breakup of his Yisrael Beitenu (“Israel Our Home”) party’s electoral alliance with the Likud from the previous election.

Now Netanyahu has undone all this; not by snatching votes from the left, or by shrinking the centre, but by splitting the centre down the middle and at the same time siphoning votes from other right-wing parties to the Likud.

The election nearly cut Yesh Atid in half, from 19 to 11 seats, and also humbled Netanyahu’s rivals for the Right’s leadership, with the secular-nationalist Lieberman losing five of his 11 seats, while religious-nationalist Naphtali Bennett’s Bayit Yehudi (“Jewish Home”) shrank from 12 to eight seats.

Much of the electorate the centre-left Lapid lost migrated to the centre-right Kulanu party, which won 10 seats. Headed by Netanyahu’s former communications minister Moshe Kahlon, whose agenda is economic, this faction is now poised to succeed Yesh Atid as Likud’s senior coalition partner. However, this partner’s size remains a third of the prime minister’s faction, and its leader generally shares Netanyahu’s views concerning the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Moreover, Netanyahu’s previous partners forced him to exclude from his coalition the ultra-Orthodox parties that had been his loyal partners over the years. This time around ultra-Orthodoxy will likely be back in his fold, thus providing a new configuration whereby Netanyahu’s management of foreign affairs faces no serious challenge within his cabinet.

His coalition will likely not allow Netanyahu similar freedom domestically.

Theoretically, the coalition talks that now begin might still produce an unexpected configuration involving Lapid and, even more improbably, Labor. In reality, all expect Netanyahu to produce the centre-right-religious coalition that the voters have allowed him to assemble.

Such a coalition’s lynchpin will be Kahlon, whose demand to be finance minister had been heeded already during the campaign, when Netanyahu, facing a mass rally in downtown Tel Aviv, vowed to install the popular, soft-spoken, 54-year-old Kahlon at the Treasury.

The former auto-parts dealer’s popularity stems from his successful deregulation of the cell-phone market earlier this decade, easing the licensing of new competitors and lifting assorted operators’ fees, all of which slashed rates sharply.

Having done all this as communications minister, Kahlon soon afterward became welfare minister. It was in that position that he and Netanyahu had a falling out, the details of which have never been publicly revealed by either. It appears that Kahlon wanted more social spending in the aftermath of the social protests that swept Israel in spring 2011. In any event, the following year he resigned abruptly, said he was taking a timeout from politics, and spent a year at Harvard studying management, before returning and launching his new party.

Kahlon’s political flowering is emblematic of Likud’s economically split personality, which will be at the centre of the new government’s challenges.

The social protests that engulfed Israel four years ago never fully subsided. Driven by a general refusal to accept higher costs for housing, education, and food, compared with most other OECD states, the protest first fuelled Lapid’s rise and now Kahlon’s. Netanyahu understands he must address this demand for change.

However, Netanyahu’s remedies are generally market based, most notably a land-privatisation reform, whereas Kahlon’s ideas are often either interventionist – like subsidising kindergarten tuition and daycare fees for the poor and capping bank fees for low-income depositors – or populist – like abolishing value-added-tax on food.

From its inception, Likud brought together populists and free marketeers. The well-born and American-educated Netanyahu personifies the latter, particularly since slashing Israel’s social safety net as finance minister a decade ago. The humbly-born Kahlon hails from the other tradition, highlighted by an economic plan that he introduced during his campaign, which he said should cost NIS 45 billion (A$15.5 billion) without specifying how it would be funded.

Kahlon is not a classical populist. He understands economics better than most politicians and is a great believer in deregulation, which he now promises to bring to the banking industry. He also shares Netanyahu’s belief in land reform, which is likely to be the first thing the two will try to introduce. However, his penchant for public spending may generate friction between him and Netanyahu, as might Netanyahu’s potential fear of Kahlon’s possible return to Likud as his aspiring successor.

An additional fiscal challenge that any narrow coalition will likely face will be demands from its ultra-Orthodox partners. These parties will expect expanded budgets for their educational institutions and assorted tax breaks for their constituents and their large families, demands that had no equivalents among the liberal partners Netanyahu had in his previous coalition. Keeping intact Israel’s universally acclaimed budgetary discipline and low debt will therefore constitute a major test for the fourth Netanyahu government.

Equally testing will be the diplomatic front. At this writing, while it seems very likely Kahlon will be finance minister and Moshe Ya’alon will remain defence minister, there is no indication who will be foreign minister. Whoever it is will have to first of all address strained relations with Washington.

Following Netanyahu’s speech to Congress last month, which US President Barack Obama and many in the Democratic Party took as an offence, Washington’s response to Netanyahu’s victory has been cold. Obama waited two days before calling Netanyahu to congratulate him, and more importantly, the White House said through its spokesman that it will reevaluate its longstanding policy of vetoing of anti-Israeli initiatives at the UN.

The American warning is explained as a response to Netanyahu’s statement during his campaign that he no longer backs Palestinian statehood, a statement he later qualified saying it did not refer to the two-state solution’s desirability, but to its current feasibility, as long as President Mahmoud Abbas pacts with Hamas and refuses to recognise Israel as a Jewish state, and the region is under heightened threat from the spread of Islamist groups like ISIS.

Diplomats assume that the Netanyahu-Obama rupture will not be truly healed during the remainder of the current presidency. From his viewpoint, Netanyahu faces about a year in which his task will be to resist Obama’s pressure before Washington becomes immersed in the next presidential race.

It is an assessment many dispute, warning that relations with Washington should never have become this tense, and that repairing them is much more urgent, and worth a higher price, than Netanyahu seems prepared to admit.

Netanyahu, in sum, opens his fourth premiership politically empowered and diplomatically embattled. It is an ironic inversion of his situation just a few weeks ago, when he launched a resounding diplomatic offensive before returning home to what many assumed was the beginning of his political end.

Tags: Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

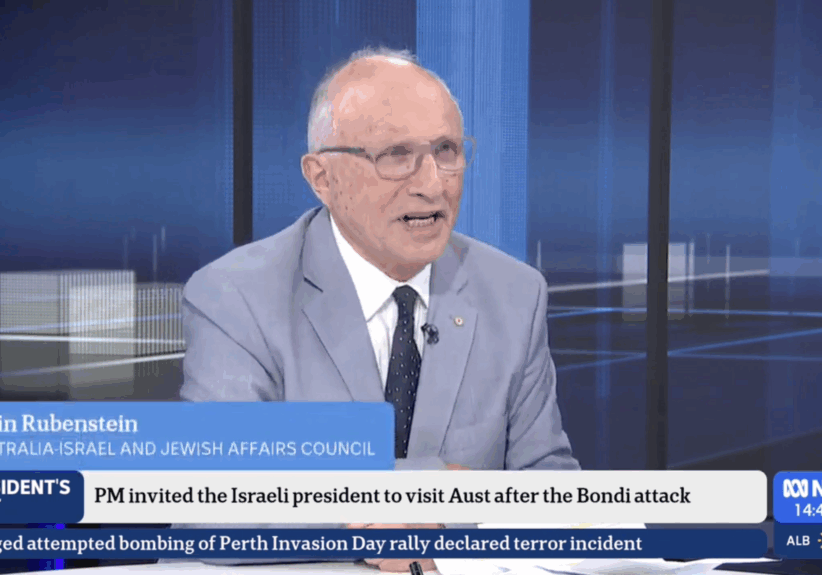

Herzog visit comes at a profoundly significant moment for the Jewish community: Arsen Ostrovsky on BBC radio