Australia/Israel Review

To Bibi or Not to Bibi

Oct 26, 2022 | Amotz Asa-El

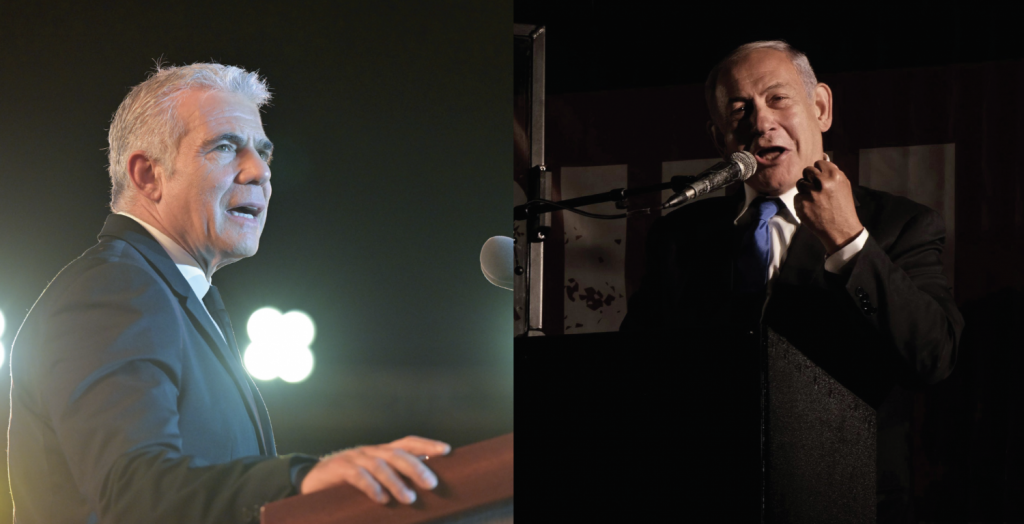

It appears as static as the Dead Sea. With the November 1 general election less than two weeks away, polls detect almost no electoral movement between the right-wing alliance headed by Opposition Leader Binyamin (“Bibi”) Netanyahu and the rival configuration headed by Prime Minister Yair Lapid.

Netanyahu’s Likud, Israel’s largest party, is polling around 30 of the Knesset’s 120 seats, the same as it currently holds, while Lapid’s Yesh Atid (“There is a Future”) polls 25. Though this figure is more than 50% higher than Lapid’s current 17 seats, the addition is coming almost fully from other anti-Netanyahu parties, and does not shift the balance between the two “blocs” dominating Israeli politics.

Netanyahu’s partners in the pro-Likud bloc are three long-time allies, the two ultra-Orthodox parties, Shas and United Torah Judaism, and the ultra-nationalist Religious Zionism party. The three parties currently poll a combined 29 seats, which means that, according to the polls, Netanyahu and his allies are close to winning the 61 seats they failed to gain in the last four elections, but may fall just short.

Lapid’s key partner is Defence Minister Lt-Gen (res.) Benny Gantz, a former IDF chief of staff whose National Unity party includes hawks like Justice Minister Gideon Sa’ar, a former Likud minister and party chairman, and doves like Lt-Gen (res.) Gadi Eisenkot, who succeeded Gantz as IDF chief of staff. National Unity is polling 12 seats, suggesting two of the 14 seats currently held by Gantz and Sa’ar will shift to Lapid.

To Lapid’s right in the anti-Netanyahu camp stands Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman, a secular hawk with a strong following among Russian-speaking voters, whose Yisrael Beitenu (“Israel is Our Home”) party is polling five seats, meaning that two of its current faction’s seven seats may migrate to Lapid.

On Lapid’s left flank stand Labor and Meretz, which are also predicted to win roughly five each, lower than their current seven and six seats respectively, with the balance also largely shifting to Lapid.

Further to the left, Lapid’s Arab ally, Mansour Abbas and his Ra’am (an acronym for United Arab List) party is polling four seats, the same as its current size.

Finally, the larger, mostly Arab, multi-party alliance that did not join Lapid’s coalition, known as the Joint List, has lost one of its constituent parties, the radically anti-Zionist Balad (acronym for National Democratic Alliance), which is running independently. According to all polls, Balad will not pass the electoral threshold of 3.25% and without it, the Joint List is polling roughly four seats, just above the electoral threshold, down from its current six.

The splintering of the Arab vote, and the prospect that some Arab-majority parties will fail to enter the Knesset, means that the Arab electorate’s generally low turnout – 44% last year as opposed to the overall electorate’s 67% – may have major impacts this time around.

The Joint List’s breakup began with Abbas’ independent run last year, which was followed by his revolutionary decision to join the coalition, and thus depart from the historic insistence by Israel’s Arab majority parties on staying out of any Zionist-led Israeli government.

The Arab electorate’s conduct will be nationally crucial in two ways. Ideologically, it will be a referendum of sorts about Abbas’ integrationist policy. Politically, if either Ra’am or the Joint List fail to cross the electoral threshold, Netanyahu will likely be handed, indirectly, the extra seats he needs in order to return to the premiership.

The drama on the extreme left of the Israeli political spectrum is paradoxically reflected by what is happening on its opposite far-right end.

Former prime minister Naftali Bennett’s decision to take a time out from politics has left his long-time ally, Interior Minister Ayelet Shaked, the task of attempting to hold on to the seven seats Bennett won last year. Polls suggest she is not succeeding and her Bayit Yehudi (“Jewish Home”) party will fail to even cross the electoral threshold.

Polls suggest that the original seven seats held after the last election by Bennett and Shaked’s Yamina (“Rightwards”) party are migrating, almost fully, to the Religious Zionism party. This party is headed by ultra-hawks Bezalel Smotrich, a former transport minister who says he wants to be defence minister, and Itamar Ben Gvir, an anti-Arab provocateur and a disciple of racist Rabbi Meir Kahane. Kahane was barred from politics because of his racism in 1988, before his assassination in 1990 in New York. Ben Gvir hopes to be minister of internal security.

These, in brief, are the election’s contours in terms of the political numbers game. Meanwhile as in the last four elections, the political agenda boils down to one issue: Netanyahu.

He is the man who, until last year, served as prime minister for 12 straight years, in addition to another three in the 1990s, and has led Israel longer than anyone else, including Israel’s founding father David Ben-Gurion.

Netanyahu’s indictment two years ago on charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust has divided Israeli society, and produced the political paralysis which the approaching election, Israel’s fifth in less than four years, will again try to undo.

Netanyahu’s attacks on the judiciary, and his public allegations that police conspired against him, along with the prosecution, the media and the courts, have frightened away a large part of his original following.

Represented by people like Gideon Sa’ar, who served as Netanyahu’s minister of education and interior, and Benny Begin, the son of Likud founder Menachem Begin, this right-wing anti-Netanyahu electorate feels that defending Israel’s judiciary from Netanyahu is right now more urgent than the hawkish agenda with respect to the Palestinians and the West Bank that they share with him. Others on the right, like Avigdor Lieberman, who once was the Likud party’s director-general, oppose Netanyahu for his ironclad alliance with, and fiscal generosity towards, the ultra-Orthodox parties.

Between them, the defection of these once supportive constituencies now deprives the pro-Netanyahu bloc of about one-third of its historic electorate. Even so, more than a quarter of Israeli voters remain staunchly loyal to Netanyahu regardless of what is said or written about him, substantially more than any rival politician.

Eager to secure the Knesset majority he failed to win in his last four attempts, Netanyahu has tried to steer the election’s focus away from his own personal situation and onto the Lapid Government’s performance, on two fronts. The first is the economy.

Holding aloft an apple in a Jerusalem supermarket while facing a random collection of shoppers, the former prime minister declared: “Take down this Government, and we will bring prices down!” Netanyahu apparently believed that he could harness the distress caused by the global inflation crisis to win votes.

Israeli prices have indeed been rising in recent months, but at an annual rate of 4.6%, which is among the lowest in the world, as is the 3.4% unemployment rate. Meanwhile, economic growth, at 4.6%, is almost the highest in the developed world. Netanyahu has thus largely abandoned his economically-focused campaign over recent weeks, apparently realising Israeli voters don’t feel that economically desperate.

A second effort to change the election’s subject came in the diplomatic realm, after Lapid struck a deal with Lebanon on Oct. 12 that regulates access to a Mediterranean gas field in the two countries’ adjacent offshore Economic Exclusion Zones (EEZs).

Netanyahu charged that the deal, which was mediated by the US, forfeited some of Israel’s territorial waters. His government, he said, would undo the deal. However, when the deal’s terms were published, it became clear that it did not affect Israel’s territorial waters as such, which extend 12 nautical miles under international law, but only the EEZ waters that sprawl to their west for another 188 nautical miles. Netanyahu has recently backtracked, and now says he will improve the deal rather than cancel it.

As a campaign issue, the gas deal died quickly, and it appears to have swayed almost no voter either way, according to the polls. In its final weeks, the focus of the campaign thus returned to Netanyahu’s legal situation, and forcefully so, after Religious Zionism’s Smotrich said he would present a bill to erase the Israeli laws creating fraud and breach of trust offences, the main offences for which Netanyahu has been indicted (he also faces one charge of bribery).

Smotrich says this legislation will not be retroactive, and thus would not affect Netanyahu’s trial. However, his bill, which would also allow the Knesset to overrule the Israeli High Court if it declares legislation unconstitutional, places the constitutional crisis created by the charges against Netanyahu at the heart of Israel’s 25th general election campaign.

Chances are, therefore, that if Netanyahu gets the votes to return to the premiership, the political and legal drama that has already defined his recent career will reach new heights.

Conversely, if he fails again to win a majority, chances are believed to be high that Netanyahu’s own Likud colleagues will make him clear the stage. In such a case, an alternative Likud leader should easily be able to build a solid coalition with Gantz, and possibly also with Lapid and Lieberman, although teaming up with either of the latter might be vetoed by the ultra-Orthodox parties, who distrust both intensely.

If indeed Netanyahu’s colleagues do end up removing him, what they will tell him is clear: we gave you five chances, we can’t give you a sixth. You have a trial to face, and we have a country to run.

Tags: Binyamin Netanyahu, Elections, Israel, Yair Lapid