Australia/Israel Review

Study reveals stark ignorance on Australia and the Holocaust

Mar 2, 2022 | Naomi Levin

After the Holocaust, an estimated 36,000 Jewish survivors came to make Australia their home. These arrivals tripled the size of the existing Australian Jewish community, according to a new report by the Gandel Foundation and Deakin University, and made an indelible mark on the broader Australian community.

Their experiences are mostly well-known to their families and the Jewish community, but this new study has found that non-Jewish Australians are not as familiar with the details of the Holocaust, and especially not those parts of its history most relevant to Australia and its development as a nation.

To coincide with International Holocaust Remembrance Day on Jan. 27, the Gandel Foundation and Deakin University published the Holocaust Knowledge and Awareness in Australia Survey.

This research is full of insights, headlined by the finding that one in four Australians have little to no knowledge about the Holocaust.

However, this article will focus on the report’s important finding that, despite the Holocaust being, in the words of the researchers, “part of the Australian story”, most respondents had very little knowledge of Australia’s connections to the Holocaust.

One part of the survey sought to gauge awareness of three key events linking Australia to the Holocaust. The first was the arrival of the HMT Dunera in 1940 with 2,542 German, Austrian and Italian “enemy aliens” aboard, many of them German and Austrian-born Jewish refugees. After a perilous journey, the passengers were interned on their arrival, until the British Government conceded they posed no threat, and they were released into the community or returned to the UK. Many of the passengers went on to make important contributions to Australian society.

Of those surveyed, 57% did not know anything about the Dunera episode, while a further 26% provided an incorrect answer when asked about it.

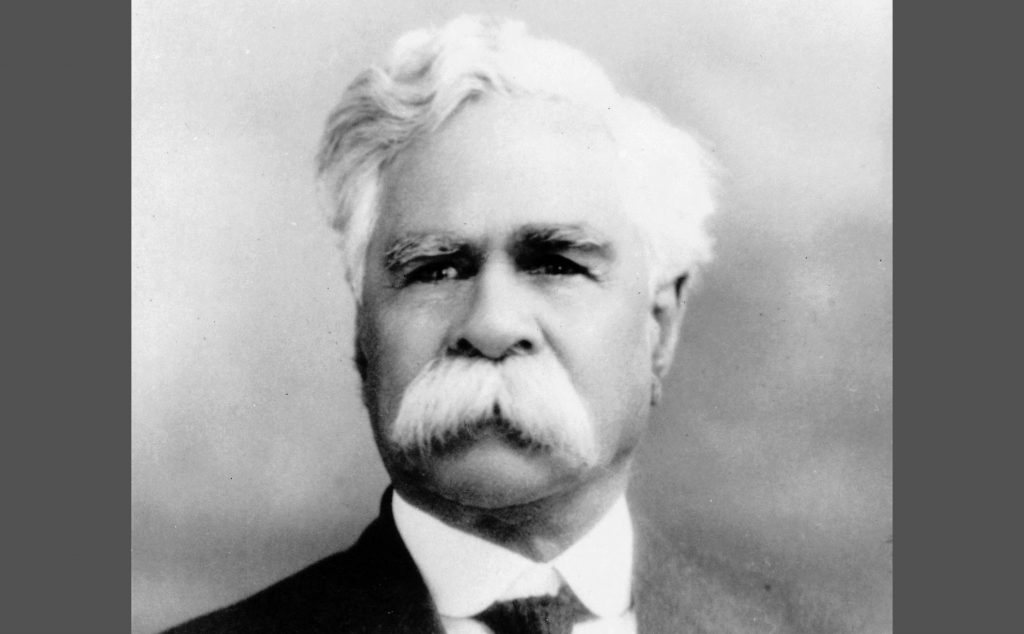

A second key event referred to by researchers was the actions of William Cooper, an Indigenous elder, who, one month after the Kristallnacht pogroms in Germany in 1938, led a delegation to the German Consulate in Melbourne to protest against violence against German Jews. At the time, Cooper and his delegation were turned away. However, in 2020, Felix Klein, the German Commissioner for Jewish Life and the Fight Against Antisemitism, issued an official apology to Cooper on behalf of the German Government. The apology was symbolically accepted by Indigenous elder Dr Lois Peeler.

Of those surveyed, only 15% knew about William Cooper’s remarkable protest.

The third key event respondents were asked about was Australia’s response to the Evian Conference, an international meeting convened in France in 1938, and attended by 32 countries, in a failed attempt to address the problem of German and Austrian Jewish refugees wishing to flee persecution by Nazi Germany. Asked to accept Jewish refugees, Australia’s delegate to that conference infamously told conference organisers that “as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one.”

In 2018, Liberal and Labor MPs apologised in Parliament for Australia’s “indifference” 80 years earlier. Liberal MP Stuart Robert, now Minister for Employment in the Australian Government, asked that the apology be formally presented to Yad Vashem and kept alongside the text of Australia’s statement from 1938.

Of those surveyed, just 11% knew about Australia’s approach to the Evian Conference.

Drawing on these results, the study’s authors recommend that more be done to research and distribute resources to address gaps in Holocaust knowledge, especially as it relates to Australia.

Writing in the Australian Jewish News (Feb. 11, 2022), Dr Hilary Rubinstein, editor of the Victorian edition of the Australian Jewish Historical Society’s Journal, explained there is already a mass of historical research on Australian connections to the Holocaust, including documentation on Australians of all political stripes who opposed the Nazi regime and advocated for Jewish refugees.

Monash University’s Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation also has a database of more than 180 memoirs published in Australia by Holocaust survivors. They chronicle the experiences of Holocaust survivors from Czechoslovakia to China who went on to build a new life in Australia.

While it is reassuring to know that the knowledge is available, it needs to be disseminated. Why? As the study’s authors note: “Australians’ understanding of their own country’s connections to the Holocaust is poor. This may lead to the impression that the Holocaust is of no relevance in the Australian context.”

The Gandel Foundation study recommends additional efforts to address gaps in knowledge, including on Australia’s connection to the Holocaust, via the programs offered at local Holocaust centres, through teacher professional associations and by developing relevant teaching materials.

Not only does the Holocaust continue to be of relevance to Australians as an acknowledgment of its role in the “Australian story”, but as historical amnesia and historical ignorance grow, Holocaust denial and distortion blossom. In addition to the other strong reasons for doing so, teaching Australians why the Holocaust is relevant to them is one essential key to minimising the spread of Holocaust distortion, as well as an important step in reducing the growing prevalence of antisemitism in the community.