Australia/Israel Review

Israel’s great sovereignty debate

Jun 30, 2020 | BICOM

Background and implications

As early as July 1, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu could ask the government or Knesset to approve a plan to extend Israeli law (often referred to as “annexation”) to areas of the West Bank. The details of the plan have not yet been released, but according to the new government’s coalition agreement, any step must be coordinated with the US while maintaining regional stability and existing peace agreements. This is a Q&A primer on the Israeli context and significance of extending sovereignty in the West Bank.

Why now and what does the Trump plan say?

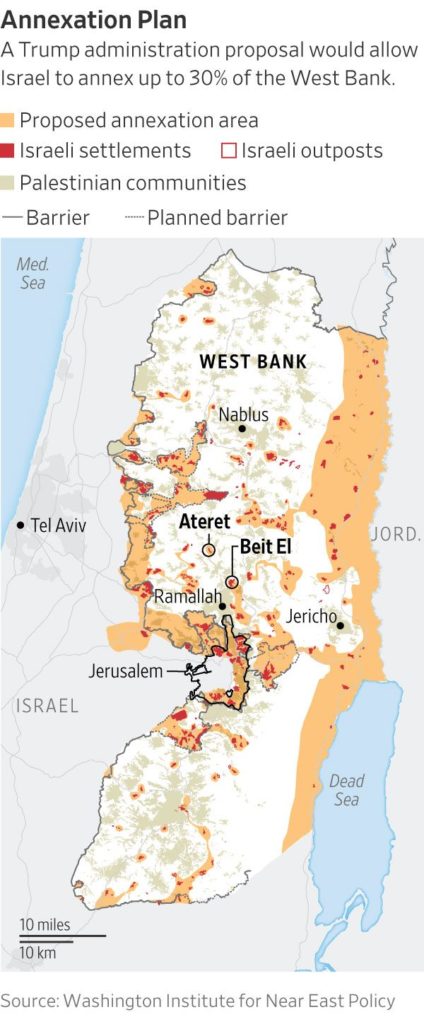

There has been a US shift, under the Trump presidency, on the conditions and the timing for applying Israeli sovereignty to parts of the West Bank. All previous US administrations had rejected any Israeli move outside the context of a peace agreement and coordination with the Palestinians. The “Prosperity for Peace” document, known as the Trump peace plan, has provided Israel an opportunity to apply sovereignty in up to 30% of the West Bank in advance of future negotiations with the Palestinians. However, reports suggest the US has conditioned its recognition of Israeli sovereignty in the West Bank on four terms: the completion of the work of a joint US-Israeli mapping committee; Israel agreeing to suspend construction in parts of the West Bank that are not designated to fall under Israeli sovereignty; the Prime Minister communicating to the Palestinians that he will negotiate, in good faith, on the basis of US President Donald Trump’s peace plan – i.e. a two-state solution; and agreement on the plan between Netanyahu and his coalition partners in Blue and White.

The Trump plan outlines a political agreement between Israelis and the Palestinians in which Israel can apply “the law and the administrative and jurisdictional regulations” in areas of the West Bank that are not allocated to a future Palestinian state, and in return has to begin negotiations with the Palestinians for their statehood within four years. Prime Minister Netanyahu has remained silent so far about when and where Israel might apply its sovereignty in the West Bank. Despite promising to bring the Jordan Valley and all settlements under Israeli law prior to the March 2020 election, political realities have meant Netanyahu and his Blue and White coalition partners agreed that only after July 1 can the Israeli government bring the issue to the cabinet and/or Knesset.

According to the Trump plan, a future Palestinian state would rule more territory than the Palestinian Authority (PA) does now – although less than what Israel offered at Camp David in 2000 and during the Annapolis talks in 2008. Israel could be required to relinquish about half of what is currently referred to as Area C (30%) to the PA, which is already in control of 40% of the West Bank, as well as transfer to the future Palestinian state territory in the western Negev that equals approximately 15% of the West Bank. The allocation of land in the Trump plan could mean that “approximately 97 per cent of Israelis in the West Bank will be incorporated into contiguous Israeli territory … the Jordan Valley, which is critical for Israel’s national security, will be under Israeli sovereignty,” whilst no population centre would move from Palestinian to Israeli control.

What is the legal status of the West Bank?

Immediately after the 1967 Six-Day War, the Israeli cabinet held a debate about what to do with the newly acquired territory of the West Bank. Some wanted to keep hold of the ancestral Jewish homeland for ideological or security purposes, and others wanted to exchange the land for peace. Over the last 53 years, this debate has divided Israeli society, as well as the political establishment.

Given the Arab states’ immediate rejection of peace with Israel after the war, Israel decided to bring the governance of the West Bank under the authority of the IDF and created a military court system, which observed the provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention for civilians under “belligerent occupation”. Palestinians were regarded as a stateless people but they were given individual rights, including the right to petition the Israeli Supreme Court over legal disputes in the West Bank. Israel has treated the legal status of the West Bank differently to east Jerusalem. On 27 June 1967, Israel passed two amendments that effectively brought eastern Jerusalem under Israeli administrative law.

In 1993, Israel and the Palestinian leadership agreed to change the legal status of the West Bank. The 1993 Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements (the DOP, also known as Oslo I) outlined a framework for the transfer of self-governing authority to the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. The subsequent 1995 Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (also known as Oslo II) divided the West Bank into three non-contiguous areas, Areas A, B, and C. The PA was given full internal security and civilian control over Area A and civilian control over Area B (90% of Palestinians live in Area A and B). Israel retained full security control over Area B and full security and civilian control over Area C, excluding civil affairs issues for the Palestinians who reside in Area C, apart from the administration of the land.

Historically, Israel has justified the construction of the settlements on security grounds, i.e. grounds that the military commander is entitled to consider in accordance with international law, rather than on the basis of any claim to a sovereign right to the territory.

What are the risks of extending sovereignty?

There are several arguments as to why Israel should not extend sovereignty:

Maj.-Gen. Kamil Abu Rukun: “Annexation could lead to a wave of terrorist violence”

Rise of Violence: The IDF’s Coordinator for Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), Maj.-Gen. Kamil Abu-Rukun, has warned that annexation could lead to a “shattering of security coordination and a wave of violence and terrorist attacks.” In time, this situation could require Israel to take over the territories at a huge economic cost. Former US Ambassador to Israel Daniel B. Shapiro and John R. Allen, a retired US Marine Corps four-star general who led the security dialogue during the Israeli-Palestinian peace process under the Obama Administration from 2013 to 2014, warned that annexation of all the settlements “will create hundreds of miles of serpentine borders, with dozens of crossing points, that would be difficult to defend, requiring expensive new infrastructure and large troop deployments.”

Diplomatic sanctions: It could result in economic or diplomatic sanctions from the EU, including restricting the import of Israeli settlement products to the European market (the EU is Israel’s largest trading partner). Other aspects of EU-Israel relations could also be put on the table: from the Association Agreement and existing trade arrangements, to cooperation programs (such as Horizon Europe) and funding through the European Neighbourhood Instrument. The EU could also stop funding the PA, a move which could cost Israel millions of dollars per year, and individual EU states could also recognise a Palestinian state in order to placate Palestinian concerns about the end of a two-state solution.

Impacting ties with the Gulf states: It could freeze or curtail Israel’s ties with Arab Gulf states and so weaken the fight against Iran, as well as redirect the international community’s attention away from Israel’s existential threat. As the IDF’s former head of military intelligence Maj.-Gen. (Res.) Amos Yadlin states: “It is important that we focus on the Iranian nuclear program in our dialogue with the Americans. Iran has continued to stockpile enriched uranium; it has continued to operate advanced centrifuges and has shortened the time to reach the nuclear threshold from one year to half a year. The world’s support for taking more steps to stop Iran is vital, as is the open and covert cooperation with the Arab world against Iran. But an act of annexation will focus the international community’s attention on Israel, and not on Iran…” And on 13 June, the UAE’s Ambassador to the US, Yousef Al Otaiba, wrote in Yediot Ahronot that “Annexation will definitely, and immediately, reverse all of the Israeli aspirations for improved security, economic and cultural ties with the Arab world and the United Arab Emirates.”

Jordan’s King Abdullah has been warning of the potential for “massive conflict” if Israeli plans go ahead

Destabilise Jordan: Maj.-Gen. (Ret.) Amos Gilead, a former director of the Political-Security Staff in the Defence Ministry, has argued that the application of sovereignty to the Jordan Valley will not produce any strategic benefit for Israel. He recently wrote: “The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has become Israel’s ally and has provided Israel with a deep strategic security zone that runs all the way to its border with Iraq. This is a security zone that, as opposed to the past, has not been used by terrorists to infiltrate Israel. All of that is liable to change the moment that Israel annexes [territory in the West Bank], which is a step that Jordan holds to be a violation of the peace treaty.”

Undermine peace agreements: Jordan and Egypt have called for Israel not to take unilateral steps in the West Bank. Jordan’s king has warned of a “massive conflict” with Israel and said that all options remain on the table in response to such a move, whilst Egypt has expressed concern that such a move would strengthen Hamas and Islamist forces in the Sinai Peninsula. Furthermore, according to Joel Singer, Israel’s legal advisor during the Oslo talks, annexation would violate Article 37(1) of the Oslo Accords which contains a clear undertaking that “[n]either party shall initiate or take any step that will change the status of the West Bank and Gaza Strip pending the outcome of the permanent status negotiations.” Palestinian Prime Minister Mohammed Shtayyeh recently said annexation would also end the possibility of a two-state solution acceptable to the Palestinians and lead the PA to unilaterally declare an independent state along the 1967 partitions, with Jerusalem as its capital.

International lawsuits: It could also open up Israelis to international lawsuits. Israel’s Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit has warned that extending sovereignty may increase the chances that the International Criminal Court (ICC) will rule in the next few months that it does have jurisdiction over Palestine, which could lead to criminal investigations against IDF soldiers and officers, government officials, and heads of municipalities in the West Bank.

Complicating land swap agreements with the Palestinians: Applying Israeli law beyond the 1967 Green Line could make it harder for Israeli governments to gain Knesset approval to withdraw from land in a future peace agreement. The ‘Basic Law: Referendum’ states that at least 80 MKs (or, in the alternative, a vote of at least 61 members and a majority of all Israelis through a general referendum) must approve any agreement by the Israeli government that will result in a situation where “the law, jurisdiction and administration of the State of Israel shall no longer apply to territory in which they currently apply.”

What are the advantages of extending sovereignty?

What are the advantages of extending sovereignty?

Finalise Israel’s borders: Supporters of applying Israeli law in the West Bank argue that such a move would allow Israel to finalise its borders for the first time since its establishment in 1948. All Israeli governments have opposed a complete withdrawal to the former armistice lines, a position generally accepted by the international community. There have also been provisions in most peace negotiations with the Palestinians for land swaps where Israel would retain major settlement blocs close to the border, although no agreement has been reached on the exact size.

Control eastern border: The opportunity to maintain Israeli control over the Jordan Valley is seen as a key advantage to extending sovereignty. Historically, this has received broad support from across the political spectrum as it provides Israel with valuable strategic depth. Former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin said Israel should maintain control over the Jordan Valley “in the broadest meaning of that term”. Furthermore, Brig.-Gen. (Res.) Yossi Kuperwasser argues that extending Israel’s sovereignty to the Jordan Valley will send a clear message that Israel is determined to keep this area, which many deem critical for its security. During the 2013-14 talks between Israel and the US, then-Secretary of State John Kerry proposed installing technological means on both sides of the Jordan River as a solution for the eastern border. Israel’s Defence Minister at the time Moshe Ya’alon refuted the US plan, saying that full Israeli control of everything that entered or exited the areas in the State of Israel and the Palestinian Authority – by land, air or sea – was a mandatory condition. Without such control, Ya’alon said, Iran, ISIS and other hostile entities would take advantage of the situation like they have done in Gaza.

Timing is now: Supporters underline that today is Israel’s best chance to apply its sovereignty in the West Bank, as long as Donald Trump is US President, since the Trump plan promises US support for the move. Several reports, predominantly in the right-wing Israel Hayom, further argue that the public warnings from Arab and European leaders of dire consequences if annexation goes ahead differ from private messages sent by the same leaders. It is argued that Israel’s relations with Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states will also not be ruined. These states rely on Israel to help mitigate the Iranian threat, so why would these states choose the Palestinian issue over interests which they perceive as existential to them?

Apply now, negotiate later: Many leaders in the settlement movement argue that any plan that allows Israel to extend its sovereignty should be supported. Oded Revivi, Mayor of Efrat, says: “We have an opportunity with this president, this prime minister and this international climate and we have to seize it. For mayors of settlement towns like Revivi, Asaf Mintzer (Elkana), Nir Bartal (Oranit) and Eli Shviro (Ariel), the Oslo Agreement allocated full Palestinian control over Area A and partial control over Area B (about 40 per cent of the West Bank), with the other 60% designated as “disputed” but under Israeli control. The application of sovereignty now could reduce the size of the “disputed” land by up to half, and this opportunity must not be missed.

Greater risk of inaction: Maj.-Gen. (Ret.) Gershon Hacohen argues that if the Israeli government rejects the opportunity for sovereignty that President Trump’s plan features, Israel’s future will face exponentially higher risk potential. Israel cannot really maintain its temporary security presence in the Jordan Valley in perpetuity. Other supporters of extending sovereignty believe that the reaction of the anti-annexation camp has been exaggerated. Raphael G. Bouchnik-Chen, a retired colonel who served as a senior analyst in IDF Military Intelligence, says such visions “are dark prophecies,” “not realistic,” and “obscure the strategic significance” of extending sovereignty for the security of Israel.

Do all settlers agree on extending sovereignty?

Whilst the overwhelming majority of settlement leaders agree on the need for Israel to apply its sovereignty in the West Bank, not all settlers agree with the Trump plan’s approach. Some oppose it from a more right-wing perspective. Those who oppose it argue that the plan will result in 19 settlement enclaves (home to over 20,000 people) becoming surrounded by a future Palestinian state, which would create complicated security issues for the IDF, as well as meaning those settlements would also have no room to expand, leaving their long-term existence in doubt with little desire from Israelis to live or move there.

Other settlers reject the Trump plan on ideological grounds, citing the US condition that Israel can only annex areas if it agrees to the entire plan, including its agreement to conduct direct negotiations with the Palestinians for at least four years, and that in this period Israel must freeze all construction and demolitions in the territory earmarked for the Palestinian state, as well as possibly in other areas.

What alternative plans exist for the future of the West Bank?

Despite years of failed efforts to find a permanent solution to the conflict, many Israelis still favour separation from the Palestinians, in order to maintain the state’s Jewish and democratic character. As a result, more Israelis have taken the view that Israel cannot afford to wait and hope that the conditions that will allow a permanent status agreement will emerge, and instead must act – unilaterally if necessary – to offer practical solutions to reducing Israel’s footprint in the West Bank without jeopardising its security needs.

Policy alternatives proposed include:

Unilateral Separation: The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) has proposed that Israel should begin a process of unilaterally separating from the PA and ending Israeli rule over the majority of the Palestinian population in the West Bank, whilst at the same time entering negotiations for a permanent status agreement based on the two-state solution. The plan proposes that Israel transfer security control in Area B to the PA, similar to the authority it now has in Area A, so that a uniform Palestinian entity will be created in 40 per cent of the West Bank (A + B) that will be the foundation for the future Palestinian state. In the remaining area, the IDF will stay in 20% of the West Bank for security interests (most of which is in the Jordan Valley, including strategic sites and transportation routes), and allocate up to 25% of Area C for the development of Palestinian infrastructure and economic projects.

Minimising the conflict: This idea emerged from the centre of Israeli politics, and its most prominent advocate is Micah Goodman. According to Goodman, Israel can and should implement eight practical steps on the ground that can minimise the cost of occupation for the Palestinians without impacting the security needs of Israel until such time as conditions are conducive for a return to peace negotiations. The steps range from allocating parts of Area C for Palestinian economic development and industrial estates; building a new railroad between Jenin and Haifa and giving permission to the Palestinians to export their goods overseas; and allowing Palestinians greater freedom of movement in the West Bank.

Right-wing Yamina party leader Naftali Bennett has a controversial “stability plan” for the West Bank. (Sraya Diamant/Flash90)

The Sovereignty Movement: On the Israeli Right there are several proposals that claim to enable Israel to control all of the West Bank without ruling over the Palestinian population. Yamina leader Naftali Bennett’s “Stability Plan” calls for Israel to apply sovereignty in Area C and Palestinians living there to become full citizens of the State of Israel (approximately 80,000 people). Those living in the Palestinian-controlled areas (Areas A and B) would govern themselves in all aspects barring two elements: overall security responsibility and not being able to allow the return of descendants of Palestinians refugees. Likud MK Tzipi Hotovely advocates for delaying citizenship for the Palestinian-Arab population in the West Bank for up to 25 years under the heading of “annexation-naturalisation.”

The Regional Approach: The Israeli Peace Initiative, co-founded by Koby Huberman, seeks to combine a two-state solution with a comprehensive regional agreement, which would provide international normalisation to Israel and moral and financial support to the Palestinians, in order to help both sides pay the price for securing a peace agreement. Huberman argues that negotiations should also include Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the UAE in order to secure regional buy-in. The Arab states could provide solutions to the permanent-status issues of Jerusalem, security and Palestinian refugees.

How would extending sovereignty affect Palestinians in Area C?

Netanyahu has recently stated that Israel will not apply its laws to areas where Palestinians reside, meaning it will not need to give Palestinians Israeli citizenship. Therefore, it is expected that the US-Israeli mapping committee will exclude Palestinians by creating Palestinian enclaves. These enclaves could continue to be part of Area C or be transferred to Area B, which will make the Palestinians living there subject to Palestinian law, but under Israeli security control. Nevertheless, the IDF’s Civil Administration has begun preparations to carry out a census of Palestinians who currently reside in Area C for the possibility that some may be given resident rights if they live in land that is eventually annexed to Israel.

Applying Israeli law in the West Bank could also lead to the Israeli Supreme Court becoming overwhelmed with mass petitions or Palestinian requests for Israeli citizenship.

Conclusion

New Israeli Defence Minister Benny Gantz (left) and Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi (right) may have a crucial role in shaping any plans for sovereignty in the West Bank. (REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun)

At the time of writing, no decision has officially been made by Prime Minister Netanyahu on the extent and depth of any move. Recent media reports suggest that the smaller the amount of land annexed, the less pushback will follow for Israel domestically and internationally.

Nevertheless, a dual process has emerged in Israel which could delay Netanyahu announcing his plan. The US-Israel mapping team is yet to finalise its task and Netanyahu has reportedly suggested that the process, when completed, could happen in stages, most likely with areas closest to the 1967 Green Line being incorporated under Israeli law first, which avoids any entanglement with Jordan.

The second process has emerged under the political reality of the new unity government. The Trump Administration is reportedly demanding Blue and White’s agreement on Israel’s plan in the West Bank before it gives Netanyahu a green light to move forward with it. During the press conference with German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas on 10 June, Foreign Minister Gabi Ashkenazi reiterated that the Trump peace plan “will be pursued responsibly, in full coordination with the US, while maintaining Israel’s peace agreements and strategic interests. We intend to do it in a dialogue with our neighbours.” Alternate Prime Minister Benny Gantz and Ashkenazi have also held several talks with Netanyahu and representatives of the US Administration to try to reach an agreement.

© Britain-Israel Communications & Research Centre (BICOM – www.bicom.org.uk), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Israel, Palestinians