Australia/Israel Review

From Washington to Teheran

Oct 28, 2020 | Lahav Harkov

The coming weeks have the potential to be dramatic ones when it comes to Iran. The UN arms embargo on Iran was meant to expire on Sunday, Oct. 18, but in August the US activated “snapback sanctions,” a mechanism in the 2015 Iran deal that would cancel its “sunset clauses” lifting various sanctions on the Islamic Republic. In other words, the US tried to make sure the arms embargo would not expire – and no other country countered that move during the month in which that was possible.

Since the US left the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the deal is known, in 2018, the other parties to the agreement say the US does not have the authority to reinstate sanctions, and they will view the embargo as having been lifted. However, the US argues that sanctions and the snapback are part of UN Security Council Resolution 2331, which lists the US specifically as a party, and not just the JCPOA.

All of this is to say that in upcoming weeks there could be a showdown between Russia and China, which want to sell Iran weapons, and the US, which has been using its economic might to enforce sanctions on the regime for the past two years and announced further measures over the past few months.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani declared in mid-October that, from Oct. 18, “we can sell our weapons to whomever we want and buy weapons from whomever we want.”

But many experts think that Iran is not going to make a move immediately after the sanctions’ maybe-expiration date.

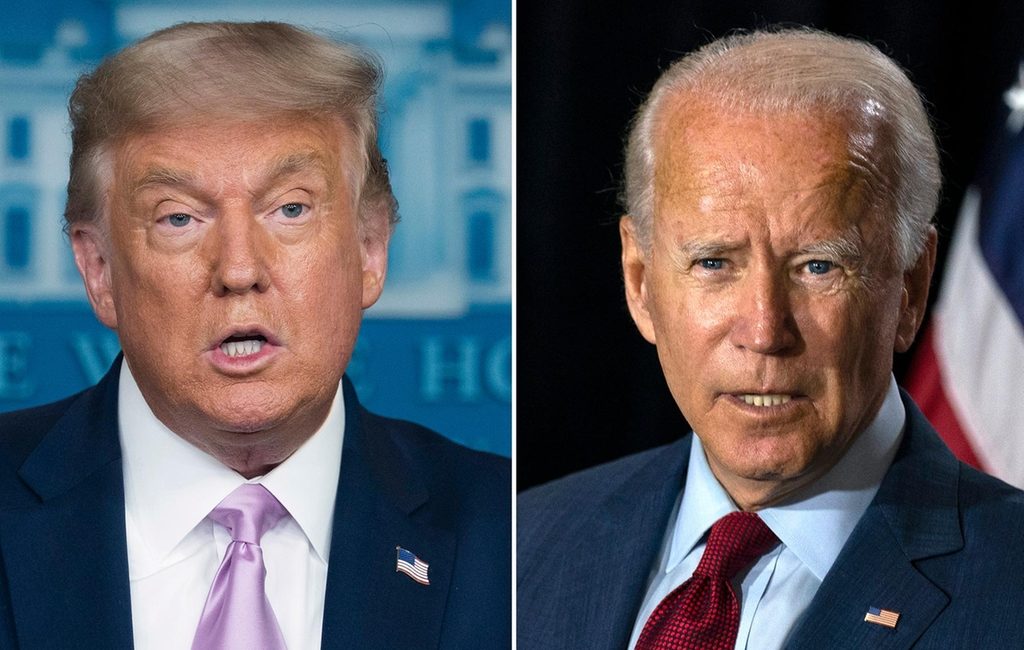

The Iranian nuclear program and its ongoing violations of the JCPOA are expected to stay in a holding position at least until after the US presidential election on Nov. 3. Before making their next move, the Iranians want to know whether US President Donald Trump will be re-elected, or whether Democratic nominee Joe Biden will take his place.

Israel is also closely eyeing the US election for a number of reasons, the Iran nuclear threat being a major one. And while Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s enthusiasm for the Trump Administration – which polling shows is matched by most of the Israeli public – is well known, both candidates’ statements on Iran have raised concerns.

Trump’s Iran policy, in many ways, is perfectly in line with what Netanyahu would want. The US left the Iran deal, with the sunset clauses and lack of enforcement that so worried Israel, shortly after Netanyahu revealed the Mossad’s sweeping operation of clearing out Iran’s nuclear archives. The subsequent “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign on Teheran is praised by much of the political spectrum in Jerusalem.

But in recent months, Trump has been saying again and again, including when Netanyahu was in the Oval Office in September, that he wants to negotiate with Iran.

“I really believe Iran wants to make a deal,” Trump said. “They’ve had a very tough time. Their GDP is down 27% because of the sanctions and all of the other things. And I don’t want that to happen…. After the election, we have to make a better deal. I do say that. We’re going to make a better deal than we would have.

“If Biden wins, they’ll make a much better deal,” Trump said, but then he added: “I’m going to make a deal that’s great for Iran. It’s going to get them back. We’re going to help them in every way possible. And Iran will be very happy.”

Trump’s theory is that the Iranians prefer a Biden victory – and all the experts the Jerusalem Post spoke to agree on that part – but if Trump is re-elected, he thinks the Iranians will realise they cannot withstand four more years of maximum sanctions pressure and will enter talks, with the US having the upper hand.

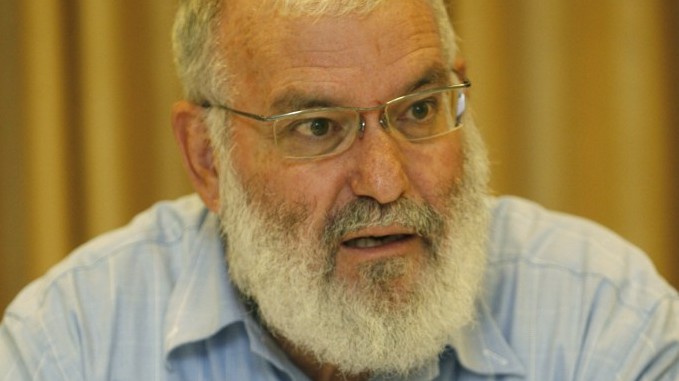

Former Israeli National Security Council chairman Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Yaakov Amidror

“Maximum pressure” of the kind the Trump Administration is putting on Iran is what brought Iran to the negotiating table last time. As former Israeli National Security Council chairman and senior fellow at the Jerusalem Institute for Strategy and Security Maj.-Gen. (ret.) Yaakov Amidror said this week: “It was proven in the past, despite what most experts said at the time, the Iranians were willing to discuss their nuclear plan when they had no alternative.”

However, Amidror said, “the Americans acted unprofessionally in the negotiations and brought a bad deal.”

Amidror was cautious in trying to predict Trump’s or Biden’s behaviour, saying that the result of the JCPOA “doesn’t mean it’ll necessarily be a bad deal next time.”

But other experts said Trump’s mercurial approach to policy, his enthusiasm for “the art of the deal” and the fact that he will be in his second term and no longer need to appeal to his voter base could lead to a disastrous result for Israel.

Col. (ret.) Udi Evental wrote an analysis of the consequences of Trump’s and Biden’s declared policies on the Iran deal.

In the scenario in which Trump is elected, Evental wrote, the Iranian regime will try to avoid “crawling on all fours” back to the negotiating table in a way that would make it look weak and susceptible to pressure.

As such, he posited, “Iran may expand the amount and the level of its violations [of the JCPOA], to have more cards to play with in the negotiations” and it may “demand compensation for its willingness to return to negotiations.”

Former Israeli ambassador to the US Michael Oren expressed concern that the Iranians will find it difficult to negotiate while under sanctions, which is what Trump seeks to lead them to do, and may lash out so the US will provide them with relief.

“They might try to destabilise the region by picking a fight with us. It hasn’t worked to pick a fight with Saudi Arabia; it kind of backfired for them. We have to remain vigilant about that,” Oren said.

In Trump-led negotiations, Oren said, the results depend on “how much more of an improved JCPOA [Trump] would want to seek in a second term.”

Iran taking a harder line could lead to Trump compromising, Evental wrote, because Trump will seek to fulfil his campaign promise to quickly close a deal with Iran that still has elements that endanger Israel, like sunset clauses, centrifuge development and not enough inspections of Iran’s nuclear program.

Then, Trump will seek to spin the bad deal as a good one.

Biden laid out his view on the Iran deal in an op-ed for CNN in September.

Biden, like the Trump Administration, vowed to “work closely with Israel to ensure it can defend itself against Iran and its proxies.”

He also said the US would continue using “targeted sanctions” in response to Iranian human rights abuses, its sponsorship of terrorism and its ballistic missile program.

As for the Iran deal, Biden wrote that he has an “unshakable commitment to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon.”

Biden’s plan is to encourage Iran to return to complying with the JCPOA, at which point the US would “rejoin the agreement as a starting point for follow-on negotiations.”

Biden was also dismissive of the Trump Administration’s attempt at snapping back sanctions, indicating that he may not enforce those measures.

In other words, Biden wants to revive the Iran deal, including the sunset clauses, and then improve on it. But he does not specify what those improvements would be.

Evental said Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser when Biden was vice president and current adviser on foreign policy, pointed out that the last two years have proven the US can effectively implement sanctions even when other world powers oppose them, and Iran is aware of that. Evental interpreted these remarks as Sullivan saying these sanctions would be an implicit threat to Iran if it refuses to negotiate a stronger version of the JCPOA.

Amidror said “the JCPOA is a terrible agreement, and even Biden says it’s bad, because he says it needs to get better.

“The question is, what is better?” he added, saying Biden realises the JCPOA did not block Iran’s path to a bomb.

Iran is “waiting for Biden to save them,” Amidror said. “I hope Biden doesn’t save them [Iran] and they [the US] can negotiate from a position of strength.”

Evental expressed concern that Biden’s emphasis in the CNN op-ed on cooperation with Europe and a lack of real levers of pressure due to lifted sanctions would end up with an unchanged JCPOA, with the same sunset clauses.

Even if Biden brings Iran back into the JCPOA fold, it has violated the deal in so many ways, including developing advanced centrifuges (and feeding uranium into cascades of such centrifuges), that it does not seem possible for Iran to roll back the knowledge and experience it has gained in that area, Evental said.

Oren said former US President Barack Obama and his team will pressure a Biden administration to renew the agreement, because Obama views it as his greatest – and only – foreign policy achievement. Staying out of it is to admit it’s a flawed agreement.

“I don’t know if the changes to the deal would be cosmetic or real changes,” he said.

Former Israeli Ambassador to the US Michael Oren

Oren thought Biden might try to extend the sunset clauses – meaning that the various levels of sanctions would expire at later dates than in the original JCPOA – and increase inspections, and Iran would probably agree to it.

But the former ambassador also said that if Biden negotiates a deal “that looks a lot like the JCPOA, that’s terrible for Israel and a prescription for war and a nuclear-armed Iran.”

Oren posited that any JCPOA-like agreement would still give Iran a path to a nuclear bomb and allow it to develop advanced centrifuges, along with the legitimacy to do so. Teheran would get tens of billions of dollars of sanctions relief. In recent years, Iran used that money to surround Israel with missiles with increasingly advanced capabilities.

“In order to stop Iran from getting a bomb, we’d have to go to war. We can’t live with a nuclear Iran, because these guys are serious. The destruction of Israel is what they’re about. It’s their essence as a regime. We’d have to act, and that means war,” Oren said.

Amidror pointed out that one of the dangers of a path to a nuclear bomb for Iran is that other countries in the Middle East will surely follow. Saudi Arabia is already moving in that direction, and he said Egypt and Turkey have also hinted that they will not agree to Iran being permitted to have nuclear weapons while they can’t.

“To stop the Iranians is so important. If there is a group of countries with nuclear weapons in the Middle East, the unstable situation can end very badly for the entire world,” he warned.

What can Israel do to try to prevent an explosive situation, regardless of who is elected president of the US in November? Make its voice heard.

That is not without its own difficulties. Israel will have difficulty strongly coming out against a Trump-negotiated deal the way it did when Obama entered the JCPOA, especially after Trump moved the US Embassy to Jerusalem, recognised Israeli sovereignty on the Golan and fostered normalisation between Israel and the UAE and Bahrain, Evental said.

Evental also thought Biden could also be very sensitive to any public opposition by Israel on this matter, because of Netanyahu’s public campaign against the Obama administration’s position, when Biden was his vice president.

Still, Evental called for Israel to make its position known and reach out to the Trump Administration and the Biden campaign as soon as possible to point out the weaknesses of the JCPOA and make sure Israel is not left to deal with its problems alone, and speak about the matter publicly as well.

“It’s important not to make the mistakes of 2015,” Oren said. “We need to be specific about what would be a good deal. The Obama Administration said no deal is good enough for the Israelis. We can’t do that this time. We have to say a good deal ends Iran’s nuclear program, removes missiles from Lebanon, eliminates advanced centrifuges and the missile program, dismantles nuclear infrastructure.

“We have to publicise this. We have never done it, and we must,” he said.

Amidror said Israel needs to tell whoever is elected president that if the deal does not address Israel’s existential threats, Israel will have to address them through force.

“A good agreement is one that dismantles Iran’s capabilities and doesn’t legitimise building nuclear capabilities – no missile tests and no developing next-generation centrifuges. It would make Iran dismantle its nuclear facilities not allow new facilities,” Amidror said.

“Our red line is we can’t let Iran get close to a nuclear bomb,” he added. “A good deal can’t give Iran legitimacy for enrichment or long-term nuclear development.”

Since both Trump and Biden want to reach an agreement with Iran, and therefore are likely to compromise to some extent, Evental thought Israel may have to back down from its “maximalist and unrealistic” demand of zero enrichment. Instead, he suggested that making Israel’s priorities clear and listing ways to improve its strategic balance with Iran would be more likely to influence whoever is in the White House next year.

Oren and Amidror stayed with the Israeli position of recent years, that Iran, the world’s leading state sponsor of terrorism, does not have a right to enrich. Oren said the “good deal” Israel seeks is realistic if the US is willing to keep up its maximum pressure campaign.

Asked whether they think Trump or Biden would be willing to keep the pressure levels high, Oren and Amidror both said they don’t know.

“The best thing for Israel would be if the US president, no matter who he is, will reach a good agreement with Iran,” Amidror said. “We don’t care how it is achieved in the end, whether it’s Biden or Trump.”

Lahav Harkov is the Senior Contributing Editor of the Jerusalem Post. © Jerusalem Post (www.jpost.com), reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.

Tags: Iran, Israel, JCPOA, United States