Australia/Israel Review

From Lebanon to Australia

Dec 19, 2018 | Naomi Levin

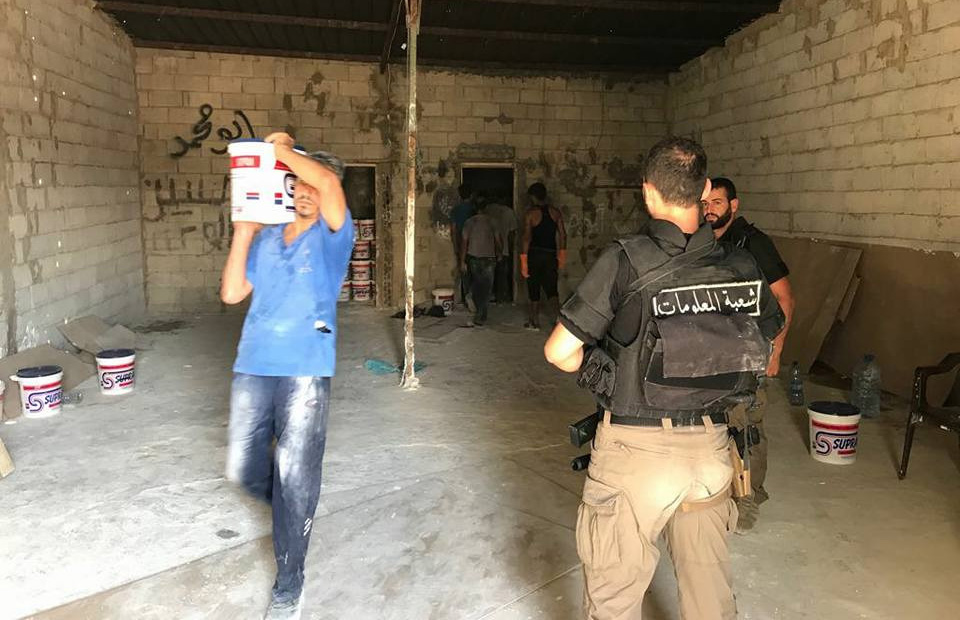

On June 1 2018, Lebanese police officers in armoured vehicles moved in on a dusty site in the Beirut neighbourhood of Ouzai.

On that site they found pallets of large buckets labelled as paint tins. In those buckets was 15 tonnes of cannabis destined for international streets.

The officers of the Internal Security Forces – as the police are known in Lebanon – arrested seven individuals over the drug discovery. No details have been released about the identity of those arrested.

While there are numerous criminal groups operating from Lebanon, one of the largest and most sophisticated is Hezbollah. Hezbollah goes to great lengths to conceal its involvement in criminal activities so it is likely we will never have confirmation whether it was involved in trafficking those drugs.

However, we do know that Ouzai is a Hezbollah-dominated neighbourhood in which little happens without the group’s knowledge and the seizure was reported in Hezbollah’s own media source, Al-Manar.

Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu put Ouzai in the spotlight at the United Nations last September, telling the world that the impoverished southern Beirut suburb actually hosts a Hezbollah missile factory under a soccer field, with residents effectively acting as Hezbollah’s human shields. Western journalists have reported the streets of Ouzai are adorned with pictures of Hezbollah fighters who died fighting alongside Assad forces in Syria.

In October, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) published its 2017-18 annual report. Tucked away in the report was a mention that the AFP worked with international partners to prevent 28 tonnes of illicit drugs from reaching Australia – 15 tonnes of this from Lebanon.

While this does not confirm that the 15 tonnes from Ouzai were destined in whole or in part for Australian streets, what it shows is that Australian law enforcement remains focussed on Lebanon – home to one of the world’s most active perpetrators of transnational crime, Hezbollah. In fact, the AFP has a counter-terrorism liaison officer stationed in Beirut.

As well as drug trafficking – and other criminal activity, such as large-scale money laundering – Hezbollah runs a Lebanese political party and a welfare network. Most dangerously though, Hezbollah is a sophisticated Shi’ite terrorist organisation that has some 130,000 missiles and rockets pointed at Israel. Its main benefactor is terrorist-sponsor Iran.

During 2018, the United States had clamped down on Hezbollah’s international fundraising and criminal activities – including establishing the Hezbollah financing and narcoterrorism team in the Department of Justice to deal with Hezbollah as one of the world’s most dangerous transnational criminal groups.

Then, in early December, Israel launched an operation to dismantle offensive tunnels Hezbollah had dug under the border from Lebanon into Israel. These tunnels threaten Israel’s northern cities and indicate the preparedness of Hezbollah to restart its conflict with Israel, which last flared in 2006, in violation of UN Security Council resolutions.

In the meantime, despite evidence that Hezbollah has been recently active in Australia and the Asia-Pacific and that a Lebanese-Australian was involved in a Hezbollah attack on Israelis in 2012, the Australian Government has not appeared to place much focus on the Lebanon-based terror and crime organisation. While there are some limited financial sanctions against Hezbollah in Australia, the Government and law enforcement agencies only recognises a small, supposed sub-entity of Hezbollah – the External Security Organisation – as a terrorist threat. This is despite bipartisan advice from the Parliamentary Joint Committee of Intelligence and Security earlier this year recommending that this listing should be expanded. It is also in contrast to advice from security experts, who say that Hezbollah is, in fact, a unified entity and delineating between “military” wings and other branches of the organisation is misguided.

This article will look at Hezbollah’s recent activities in and around Australia.

MONEY LAUNDERING AND DRUG TRAFFICKING

Hezbollah receives an estimated US$700 million a year from Iran to support its political, welfare and military operations. This is supplemented by its own “earnings” from sophisticated transnational criminal operations.

According to Emanuele Ottolenghi from the Foundation for Defence of Democracies, Hezbollah is an active participant in every stage of the illicit drug supply chain and in the production and sale of counterfeit medicines. Hezbollah is also a major supplier in the illicit tobacco market. To evade law enforcement, Hezbollah is also heavily involved in global money laundering.

The money laundering and drug trafficking are intertwined. Over the past five years, there have been numerous leads indicating Hezbollah’s activities on both these fronts within Australia.

In 2013, the AFP, the then-Australian Crime Commission (now known as the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission) and the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (Austrac) completed Taskforce Eligo. This taskforce looked at the role of serious organised crime in the alternative remittance sector, that is, non-bank services which move money between countries.

Altaf Khanani: Money launderer linked to Hezbollah

Taskforce Eligo helped to uncover suspicious activity by Pakistani national Altaf Khanani, who was moving money between Australia, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, the US, the UK and Canada, for clients including Hezbollah.

Khanani was arrested and imprisoned and the US blacklisted his money laundering business saying the company had exploited “relationships with financial institutions to funnel billions of dollars across the globe on behalf of terrorists, drug traffickers and criminal organisations”.

Taskforce Eligo also revealed that an exchange house used by an Australian money laundering operation was delivering a cut to Hezbollah for every dollar it moved.

In 2016, three men affiliated with Hezbollah were identified as illegally moving US$500,000 in and out of Australia. Again, media reported that the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission was involved in the sting.

One of these men, Mohammad Ahmad Ammar, who was based in the Hezbollah crime hotspot of Medellin, Colombia, was arrested in Miami where he was described in court documents as “a Hezbollah associate known to be involved in multifaceted criminal activity” and as working “directly with established members of Hezbollah”. Media reported that the money had been traced through Australia, Europe and Africa.

Hezbollah is also highly active in the global black market tobacco trade. David M. Luna, the past chair of the OECD Task Force on Countering Illicit Trade, has said that 15 of the world’s most active terrorist groups, including Hezbollah, rely on the sale of illicit cigarettes for revenue.

While there have been no known reports of Hezbollah connections to the sale of illicit cigarettes in Australia, a study by Mark Lauchs and Rebecca Keane from the Queensland University of Technology into Australia’s illicit tobacco market has noted that as the local taxes on tobacco products have grown, so too has the market for illicit tobacco products. Lauchs and Keane report that the global illicit tobacco market does fund terrorist groups – and it specifically nominates Hezbollah as one. They go on to suggest: “It would be naïve to assume that these criminal associations between illicit tobacco smuggling and organised crime do not exist in Australia”.

FUNDING HEZBOLLAH VIA FOREIGN CHARITIES

According to a trends and issues paper issued by the Australian Institute of Criminology, there is significant evidence of terrorist entities misusing not-for-profit organisations (NPO), particularly charities, for fundraising purposes.

This can involve setting up a ‘front’ charity, where proceeds appear to be funnelled to assist in a legitimate cause, but are actually going to a different group. Funds raised by one group are moved around to other groups that then provide the proceeds to an illicit cause.

The Australian Institute of Criminology paper, by Samantha Bricknell, highlights Hezbollah as one of the groups that have exploited charitable giving as a means of revenue-raising. Bricknell suggests that while case studies do exist of Australian not-for-profits providing terrorism financing, there are not very many, adding “This could suggest that the prevalence of money laundering/terrorism financing misuse is itself low. Conversely, it could indicate that there are low detection rates for this kind of illegal activity.”

Without highlighting particular case studies, Austrac this year released a “Red Flag Indicator” alerting the intelligence and policing community to the link between not-for-profits and terrorism funding.

They wrote, “a significant number of regional NPOs have links to foreign countries considered high risk for terrorism funding, as either source or destination countries for fund flows or delivery of services.”

Matthew Levitt, one of the world’s leading experts on Hezbollah, notes that Hezbollah receives significant financial support from the Lebanese Shi’ite diaspora. Census figures indicate more than 10% of Australian Muslims have a Lebanese-born parent – although no data was collected on whether they are Sunni or Shi’ite. Of course, not all Shi’ites would back Hezbollah.

However, Hezbollah’s local presence has certainly been demonstrated by the Hezbollah flags prominently flown in many anti-Israel demonstrations in Australia.

Out in the open: Hezbollah supporters in Sydney

Hezbollah, as well as undertaking military activities to threaten Israeli and global security, also provides social welfare in order to garner support from impoverished Lebanese communities.

Academic Shawn T. Flanigan, who undertook fieldwork in Lebanon and interviewed a number of employees of Hezbollah-affiliated NGOs, notes that Hezbollah’s welfare role is not merely a cover to fundraise for its terrorist activities. These services, funded with the help of overseas charities and the proceeds of crime, also help Hezbollah recruit militants to fight against Israel. Flanigan notes that material provided by Hezbollah’s health care services promote violent “resistance”.

Many, if not all, of Hezbollah’s health care services – as well as its education unit and social unit – are registered as NGOs by the Lebanese Government. This allows them to easily attract funding from donors.

CONCLUSION

Last year, a Sydney Morning Herald investigation revealed that a Sydney man affiliated with Hezbollah had acted as a middle-man to smuggle weapons between Chinese state-owned defence company Norinco and Hezbollah.

This investigation, together with the rest of the analysis presented here, indicates strongly that Hezbollah has a dangerous presence in Australia.

Whether it is in illicit drug trafficking, money laundering, raising money illegally and now weapons smuggling, Hezbollah is active in both our region and our nation.

While the US has, this year, established a taskforce to deal with Hezbollah’s criminal activity and the IDF has engaged its military to dismantle terrorist tunnels dug under the Lebanese border and into northern Israel, Australia has yet to take any comprehensive steps to deal with the terrorist group.

It seems clear more needs to be done.