Australia/Israel Review

Essay: That’s Entertainment – Israeli style!

Jun 2, 2019 | Amotz Asa-El

Tensions in Gaza, coalition negotiations, and Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s legal entanglements all seemed to have vanished as millions throughout the world watched the Jewish state display its new, and improbable, claim to relevance: entertainment.

Tel Aviv’s hosting of Eurovision – the world’s most veteran, lavish, and widely viewed song contest – was flashy, sassy and flawless through its three evenings, underscoring the maturation of Israeli show business.

The show, which brought to Israel singers and bands from 35 countries (including Australia) attracted thousands of tourists, and passed without either an organisational glitch nor a security incident. On stage, the only oddity was Madonna’s guest performance, which some critics found musically flat.

Otherwise, the event that was held over three nights between May 14-18 at the Tel Aviv Fairgrounds in the presence of 8,000 jubilant youngsters was a celebration of laser beams, erupting flames, and computerised graphic effects that reflected the tech-savvy with which Israel has become synonymous.

Yet, even after international pop’s moment in the Israeli sun, and even after considering zany singer Netta Barzilai’s victory last year and electrifying guest performance this year, Israel’s burgeoning status as an entertainment power is not primarily in music, but in cinema and television.

Like Israel’s food culture, which evolved from greasy falafel stands to haute cuisine restaurants, Israel’s booming film and TV industry started off as an exotic product that seldom reached foreign audiences.

Now Israeli film and TV are the toast of Hollywood, Broadway, and Cannes.

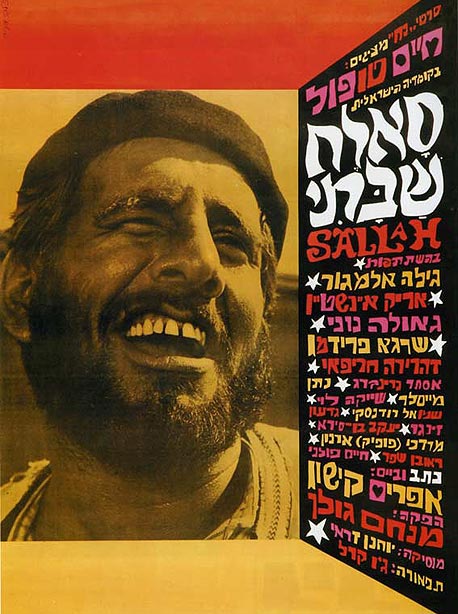

Sallah (1964) featured Topol

The original exoticism was represented by the 1964 box office hit Sallah, the first Israeli film nominated for an Oscar.

Though itself a satirical masterpiece, about an uneducated immigrant from an unnamed Middle Eastern country who outwits the entrenched denizens of the arrogant establishment, Sallah came across not as a discussion of the human condition, but as a statement about specifically Israeli problems. Moreover, its implicit vote of confidence in the Zionist enterprise’s “ingathering of exiles” was a key ideological subtext.

The genre that Sallah then inspired, some two decades of shallow comedies about encounters between Israelis of European and Middle Eastern backgrounds, went unnoticed abroad. This was with good reason – in all aspects, acting, screenplay, and cinematography, that wave was mostly substandard.

There were some exceptions over those years – like Golden Globe winner The Policeman (1971), about a cop whose career and marriage are a failure because he is too nice – but the twin turning points for Israel’s screen industry came years later: the first was a result of Israel’s wars, the second, a result of its globalisation.

The wars that were previously treated ideologically in Israeli cinema – in the spirit of the 1960 Hollywood epic Exodus starring Paul Newman – gradually became backgrounds for universal themes with no political subtext.

The pain of Israelis from their Middle Eastern wars and from the European traumas of Israel’s Jewish founders produced powerful cinema as Israel matured.

Aviya’s Summer (1988) cast iconic Israeli actress Gila Almagor as her real-life mother, a Holocaust-survivor widow who inspires her lone daughter to stand up to the neighbourhood kids who mock her after the mother shaves off her daughter’s lice-ridden hair. One of the most watched Israeli films ever, it was part of changing attitudes to the Holocaust on the part of native Israelis – from a source of shame to part of their psyche.

Aviya’s Summer (1988)

The same social sensitivity was displayed in Noa at Seventeen (1982), a high-school drama about a girl whose life in 1950s Tel Aviv is unsettled as her family’s cohesion is broken up by the kibbutz movement’s great division of those days, the battle between supporters of Israeli founder David Ben-Gurion and his opponents.

In the same therapeutic spirit, Israel’s wars gradually moved from its films’ foreground to their background.

Yes, Israelis still made heavy war films like Late Summer Blues (1987), about a group of twelfth-graders’ last summer before one of them is killed as a soldier in the War of Attrition; or Ricochets (1986), which probed, through one unit’s service in Lebanon, how war victimises all its participants.

Yet that sombre tone vanished in the romantic comedy Song of the Siren (1995). Though set against the background of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s missile attacks on Tel Aviv in 1991, it ignores the war’s bigger picture, and instead follows a 30-something advertising executive and her food-engineer fiancé as their exes return to their lives.

Similarly, the following decade’s Yossi and Jagger (2002), which won the Tribeca Best-Actor Award, was centred on a combat unit stationed in Lebanon, but was actually about a gay relationship between two infantry officers.

Yossi and Jagger (2002)

This evolution toward daily life’s travails produced hits like the Oscar-nominated Footnote (2012), a father-son drama about an aging and unsuccessful professor of Talmud who is mistakenly granted the prestigious Israel Prize intended for his successful son; and Late Marriage (2001), about a PhD. candidate in philosophy who has a secret relationship with an older divorcee while his parents repeatedly and unsuccessfully introduce him to women from their conservative, Georgian community.

Yet the Israeli film industry’s transition to content with universal resonance, and the respect this brought Israeli cinema, were but the prelude to the astonishing success in recent years of Israeli television.

Israel TV started humbly in 1968 as a lone black-and-white public channel whose first competitor took 25 years to arrive.

The original station’s products seldom reached foreign audiences, and when they did it was with purely national content, such as Pillar of Fire (1981), a highly acclaimed, 19-part documentary about the history of Zionism that was later broadcast on American and German stations.

Israeli TV’s transition to universal themes which resonated internationally came with the export of In Treatment (2005), a series that follows a psychologist’s sessions with his patients. Praised by the New York Times as “hypnotic,” the series starred the late Assi Dayan, son of war hero Moshe Dayan – a casting decision that epitomised the film industry’s transition to a post-heroic, civilian agenda.

In Treatment was also the first among dozens of Israeli TV series that conquered foreign audiences. The concept was bought by HBO, which adjusted it to the American viewership, before it was adapted in 20 other countries, winning a Golden Globe, as well as an Emmy, along the way.

The idea of buying and adapting an Israeli TV series’ concept was repeated with Yellow Peppers, about a farming family’s struggle with its adorable, five-year-old boy’s autism. The series was bought by the BBC which redid it as The ‘A’ Word, relocating it from Israel’s arid Arava Valley to England’s lush Lake District.

Israel’s wave of TV dramas spread to all genres – from soap opera Ramat Aviv Gimel, about intrigues among the rich and beautiful; through to the court thriller Your Honor, about a judge who degenerates into life in the underworld; the sitcom Traffic Light, about young men’s lives between marriage and work; the reality show The Gran Plan, where a young person’s deadlocked life is placed in the hands of three grandmothers; to the crime “docudrama” Shadow of Truth, whose episodes analyse an actual murder case, successively, through the eyes of the prosecution, defense, conspiracy theorists, and a previously unknown witness.

The Gran Plan: Hit series sold into 25 countries

In Treatment was adapted by 20 countries; The Gran Plan was reportedly sold in 25 countries; Shadow of Truth was released with subtitles in 190.

Reflecting a globalising and well-travelled Israeli society’s intense exposure to the outside world, and joining major Israeli exports – from software and drones to irrigation systems and medication – Israeli film has come of age.

Coupled with every summer’s massively attended, open-air rock concerts, the cultural hyperactivity of Israel reflects a quest for normalcy that has accompanied the Jewish state since the morning after its War of Independence.

The extent to which this normalcy has been attained is obviously debatable.

There is no debating, however, the feeling that Eurovision brought to the nation. With the thousands at the Tel Aviv Expo dancing, singing and cheering as their heroine, Netta Barzilai passed the Eurovision trophy to her successor, the Netherlands’ Duncan Laurence; with the contest’s dozens of zanily dressed bands focused on nothing but music; and with Madonna arriving for her much-heralded number in the finale – Israelis felt, justly or not, that their country has become an entertainment hub as legitimate as any other.

Tags: Israel