Australia/Israel Review, Featured

Essay: Racial tensions

Jul 1, 2020 | Ahron Shapiro

The death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer on May 25, was a breaking point for race relations in the USA, setting off massive protests that spread to cities around the world and awakened sympathies of people of all ethnicities, including world Jewry.

The masses poured into the streets, despite the coronavirus pandemic, to endorse the simple messages that Black lives matter, that the blood of minorities is not cheap and the injustices they face, past and present, need to be addressed much more vigorously.

Organising the protests is Black Lives Matter (BLM), a self-styled activist group that was born in the outrage following the shooting death of Black teen Trayvon Martin by a neighbourhood-watch volunteer in Florida in 2012. BLM soared in popularity after thousands took to the streets after another Black teen, Michael Brown, was fatally shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014.

But BLM, the group that organises protests and purports to represent these protesters, effectively insists the demonstrators endorse a series of far-flung political demands that, in truth, many would not even be aware of, let alone agree with.

These political objectives are not found on the BLM website itself but on the site of its sister organisation, the Movement for Black Lives (“M4BL”), an umbrella group founded by BLM’s organisers in December 2014. M4BL’s platform has been available online since mid-2016.

Moreover, BLM’s message to its newfound supporters appears clear: it’s their way or the highway. In a Washington Post story on BLM from June 10, M4BL strategist Thenjiwe McHarris, said she “is pleased to see the movement broadening but that it is ‘meaningless and harmful’ when people join marches and post ‘Black Lives Matter’ but do not advocate for substantive changes in policy.”

M4BL’s website explicitly spells out these policy changes that the organisation is pressuring the protesters to support, big and small. Of special concern to world Jewry, M4BL calls for cutting off all US military support for Israel, which it terms an “apartheid” state that is perpetrating “genocide… against the Palestinian people.”

“The US justifies and advances the global war on terror via its alliance with Israel and is complicit in the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people,” the brief reads, without offering evidence for the outrageous and unsupportable claim. M4BL further alleges that US military aid to Israel, which it concedes is mostly used to support the American defence industries, “diverts much-needed funding from domestic education and social programs” (that’s not how Federal budgets work).

It also makes spurious claims such as “Israeli soldiers also regularly arrest and detain Palestinians as young as four years old without due process.” (They don’t. According to the laws under which the IDF operates, Palestinian minors under the age of 12 are not criminally responsible for their actions and therefore cannot be arrested, though they can be temporarily restrained if they are creating a danger to themselves or to others, before being returned to their families.)

When informed about several major Jewish organisations that said they would withhold direct support for the BLM movement in light of their anti-Israel platform – while still supporting the Black community – Rachel Gilmer, one of the drafters of the brief, told Haaretz in 2016, “I don’t think it’s a loss” to the Black Lives Matter movement. “It’s just made it clear that they weren’t real allies.”

Anti-racist – but a blind spot on Jews?

To date, most leaders of Black Lives Matter have shown little concern about who their allies are, provided they support the platform and show up at protests or flood social media with content. As such, BLM has been troublingly silent about antisemitic posts in social media by their supporters or antisemitic incidents that have taken place during recent protests organised in their name.

For example, in Los Angeles on May 30, roving BLM demonstrators spray-painted anti-Israel slogans on synagogues and looted and torched several Jewish-owned businesses. On June 13, in Paris’ Place de la République, anti-racism protesters gathering in solidarity with BLM chanted “dirty Jews” and waved signs with inflammatory slogans such as “Israel, laboratory of police violence.”

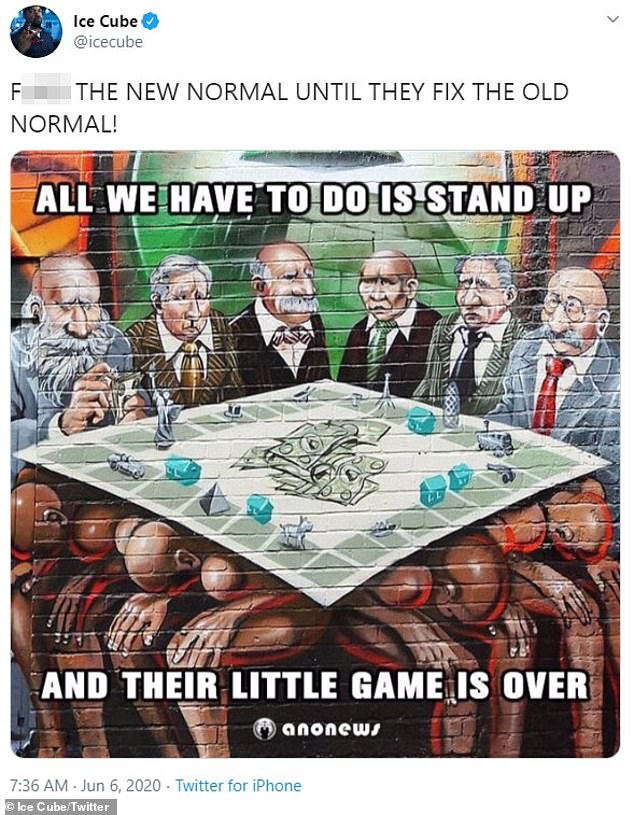

An antisemitic tweet from the rapper Ice Cube

In early June, actor and rapper Ice Cube tweeted antisemitic memes without consequence, while talk show host and activist Chelsea Handler circulated a video by Black militant and openly antisemitic “Nation of Islam” leader Louis Farrakhan, getting likes from several Hollywood A-listers before deleting it.

Black Lives Matter has also kept mum over outrageous, fabricated and factually unsubstantiated allegations circulating under its hashtag, claiming police brutality in the US was somehow a product of military-style training US police officers had received in Israel as part of international exchange programs. There were even allegations that Israeli forces taught Minneapolis police the knee-to-neck choking technique that killed George Floyd.

Stephen Pomerantz, who, following the 2001 September 11 attacks, organised many of the counter-terrorism exchanges in question for the Jewish Institute for National Security of America, has pointed out how absurd this claim is. He noted that:

“…there is no field training involved in either the conferences or trips, and no training on holds or arrest mechanics. The exchanges, which are hosted by the Israel National Police, focus on effective counterterrorism techniques.

Participants learn how Israeli law enforcement deters, disrupts, and responds to terrorist attacks. They explore the ideology of suicide bombers and other attackers, ways to de-escalate an ongoing incident, and the intelligence-gathering and sharing process.”

Yet, Rodney Bryant, who was appointed Atlanta’s police chief following the killing of a Black drunk-driving suspect by policemen in that city on June 12, came under attack in social media for having participated in Georgia State University’s Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange (GILEE) program in Israel a number of years ago.

In 2014, Bryant – who incidentally is Black – gave his own account of his work with the Israeli police which debunks the claim that US police officials who visit Israel are schooled in violent techniques. Bryant’s feedback from the program actually revealed a focus on sensitivity training and community relations.

Acting Atlanta Police Chief Rodney Bryant: Targeted for having once attended a law enforcement exchange program in Israel

“One of our greatest challenges in American policing is serving a community that is vastly more diverse than the local police department,” Bryant wrote. “Comparatively, the Israeli police are responsible for serving a variety of demographics. I was impressed by the level of community policing efforts employed by the Israeli Police to build relationships and maintain peace among such diverse populations. The mentor shadowing was considerably inimitable and having the opportunity to observe the daily operation of a station and its command staff was enlightening.”

Bryant concluded, “Although generally ensuring public safety was important, understanding the concerns of the community was equally significant.”

The fact that many BLM activists promote antisemitic views, or refuse to denounce antisemitism in their ranks, is unsurprising, UK Telegraph columnist Zoe Strimpel wrote on June 20.

“Anti-racism movements often foster antisemitism,” Strimpel explained. “This is because the most committed anti-racists see Jews as part of an imperialist racist Zionist conspiracy, represented by Israel”.

“According to their political lights,” she continued, “Israel is the world’s single biggest problem, and they believe it exists solely to egregiously and brutally oppress people of colour – including, but not limited, to their Arab neighbours. Jews, Zionists and racists unite, for them, in one toxic brain fog.”

Black antisemitism: A troubling phenomenon

Antisemitic elements in the BLM movement, unfortunately, may in part reflect the popularity of antisemitic views among sectors of America’s Black community, which according to numerous studies, is relatively high.

As UCLA law professor and popular blogger Eugene Volokh noted in December 2019 in the midst of a wave of Black-on-Jewish violence in the New York area:

“According to an October 2016 Anti-Defamation League survey, ‘antisemitic views’ among black respondents were materially more common than among whites, with 23% of black respondents scoring high on the ADL’s scale, compared to only 10% of whites.”

While the ADL seems to have stopped polling antisemitic views by ethnic group since the 2016 survey, Volokh noted that “The results remain largely the same when aggregating the ADL’s 6 surveys from 2007 to 2016; between that and the oversample of Blacks and Hispanics among the 1532 respondents in 2016, the comparison seems likely to be pretty reliable.”

In January 2020, commenting on the same wave of antisemitism, columnist Jonathan Tobin wrote about the importance of addressing the problem of Black antisemitism without losing sight of the fact that the vast majority of the American Black community are not antisemitic.

Tobin wrote: “as much as we must resist the impulse to avoid criticising Black antisemitism because of their long history of oppression, the opposite is also true. It is equally important for those calling attention to Black antisemitism to realise that Jews and Blacks are not competing for victim status. Nor is it helpful or accurate to assume that minority communities are invariably hostile, or that common ground can’t still be found.”

America’s Blacks and Jews: Historic partnerships

Encouragingly, while Black antisemitism remains a serious problem, and elements of the Black Lives Matter movement leadership appear to show little interest in combatting it, let alone welcoming supporters of Israel into their tent, the majority of the American Black community and its core institutions have much less tolerance for antisemitism and Israel-bashing.

Much of this goodwill can be traced back to historic partnerships between Black and Jewish activists which reached a peak during the American civil rights era, some of which have endured and are continuing to be nurtured to this day.

The depth of cooperation between Black and Jewish organisations during the American civil rights era would be almost impossible to exaggerate, with Jewish groups contributing vital legal assistance to the civil rights cause in virtually every landmark court case, including Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ended segregation in schools.

Dr. Martin Luther King (front row, second from right) with his friend and confidante Rabbi Avraham Joshua Heschel (front row, third from right) in 1968

Jewish groups assisted in drafting legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination based on race, colour, religion, sex or national origin, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, barring racial discrimination in voting – both of which were crafted in the conference room of the Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism, by the Black and Jewish-led Leadership Conference, which was based in the same building.

In his work A History of Jews in America, historian Howard M. Sachar estimated Jews “made up at least 30 percent of the white volunteers who rode freedom buses to the South, registered Blacks, and picketed segregated establishments. Among them were several dozen Reform rabbis who marched among the demonstrators in Selma and Birmingham.” Also very prominent among them was Dr. Martin Luther King’s friend and confidante Rabbi Avraham Joshua Heschel, a Conservative rabbi and professor of ethics.

Jewish volunteers even gave their lives in the fight for civil rights for Blacks – perhaps most famously Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, who in 1964, together with Black colleague James Chaney, were killed by the Ku Klux Klan in what became known in FBI case files as “Mississippi Burning”.

While historians note a decline in relations between the Black and Jewish communities from the mid-1970s onwards, some strong ties endured, while others revived. Nowhere are these ties more evident than at America’s oldest and most accomplished Black civil rights organisation, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People – better known by the acronym NAACP.

Founded in 1909 by a group of visionary Black, Jewish and white social reformers, and continuing to feature a rabbi on its national board today, the NAACP is aimed at correcting injustices against Black people in the context of a universal mission. According to the organisation, its mission is “to secure the political, educational, social, and economic equality of rights in order to eliminate race-based discrimination and ensure the health and well-being of all persons,” placing it in the same category as the Jewish Anti-Defamation League civil rights organisation. Indeed, the two organisations routinely work side by side.

At crucial moments in history, NAACP actually went beyond simple support for Zionism to actually lobby for Israel’s creation.

In 1972, in a JTA story about the NAACP pulling out of that year’s National Black Political Convention over anti-Israel resolutions that had been passed there, then-NAACP assistant executive director Dr. John Morsell reminded the news agency that the NAACP’s support for Israel was always a matter of principle and predated the founding of the state. He recalled that, in 1947, then-NAACP executive secretary Walter White “lobbied vigorously for [the UN’s Palestine] partition [plan] with the delegates from Ethiopia, Haiti and Liberia, and succeeded in influencing two affirmative votes and one abstention.”

While NAACP’s support for Israel has become more complex over the years, it refuses to cave in to political pressure to make the Jewish State a wedge issue. In 2017, then-NAACP President Cornell Brooks tweeted “On the issue of Palestine and Israel… we don’t necessary [sic] need a consensus but we do need to keep talking.”

The NAACP has been quick to root out antisemitism in its ranks, on several occasions censuring and removing local officials who have made antisemitic remarks. Just as importantly, the group has embraced opportunities to increase Black-Jewish dialogue in communities where antisemitic attacks have occurred to reduce antisemitism at its source.

In November 2018, former US Attorney General Eric Holder was the keynote speaker at a major NAACP fundraiser in South Carolina held under the theme of “saluting our Jewish and Black Founders.”

“We are once again at a time in our nation when we need to band together to eradicate hatred and work together to advance the cause of civil rights,” Holder said, “We must resist those who would try to put asunder the historic Jewish/Black alliance that has meant so much in the fight for equality for both groups.”

Love thy neighbour

Hasidic Jews march for Black Lives Matter in Crown Heights, once the site of Black riots targeting the local Jewish community

While Jewish and pro-Israel activists debate how to address the problems within the Black Lives Matter movement, disparate Jewish communities are not allowing the controversy to silence them. Rather, they are continuing to raise their voices in support of their Black neighbours, letting them know that whatever objections they may have with elements of BLM as a political movement, on a personal level, they have their support.

Virtually all mainstream American Jewish organisations have publicly supported the main goals of the Black Lives Matter movement, if not the details of the controversial policies of BLM as an organisation.

And so it was, on June 7 in Crown Heights, New York – once the scene of Black riots against the local Jewish community in the early 1990s – where hundreds of members of the Chabad Hasidic sect marched down Eastern Parkway in a show of brotherly solidarity with their Black neighbours.

“Whoever can protest to his townspeople and does not, is accountable” read one sign, quoting a passage from the Talmud.

A rally organiser told the Forward that speaking out against police violence was a religious obligation.

“If an agent of the justice system can murder a person in cold blood that doesn’t just call out as a human issue, as an American issue, to me that calls out as a Halachic issue, a Jewish law issue,” he said. “It should call out to every Jew.”

Tags: Antisemitism, Black Lives Matter, Israel, Racism, United States