Australia/Israel Review

Essay: Antisemitism – What everyone needs to know

Sep 19, 2025 | David Harris

Understanding an infinitely adaptable conspiracy theory

The following short essays are excerpted from a forthcoming book, Antisemitism: What Everyone Needs to Know®, written by David Harris, the long-serving former CEO of the American Jewish Committee, and published by Oxford University Press. It will be available for sale on October 6, 2025, at the recommended retail price of US$18.99 for the paperback version.

What is antisemitism in plain speech?

Above all, antisemitism is an enduring and infinitely adaptable conspiracy theory. It ascribes to Jews, as a group, malevolent characteristics and aims. Even if historical circumstances should change over time, those essential characteristics and aims do not. Thus, for hardcore antisemites who seek off-the-shelf answers for the world’s calamities, the Jews offer a convenient, one-size-fits-all answer. Jews are evil incarnate. They are the devil incarnate. They are Satan incarnate. They are the anti-Christ.

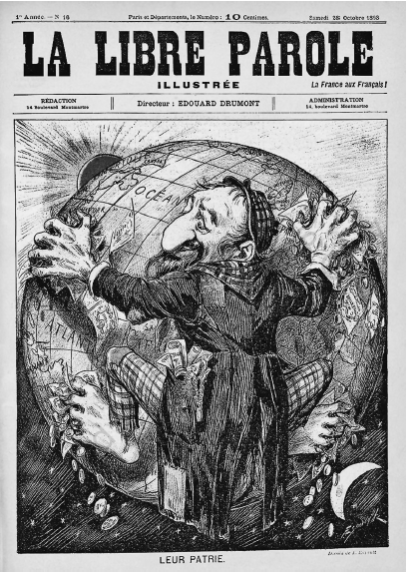

According to this worldview, or, more precisely, demonology, the Jews are always plotting, scheming, deceiving, cheating, undermining, sabotaging, or manipulating. They are at any moment conspiring with Masons, Bolsheviks, globalists, cosmopolitans, Black people, even Nazis to undermine the established order and gain power. They are clannishly out for themselves at the expense of others, seeking political and economic control, starting wars for their own benefit, spreading diseases to the non-Jewish population, pursuing other nefarious aims to weaken and dominate society at large (see image on next page).

An 1893 cover of La Libre Parole, a notoriously antisemitic newspaper published by Edouard Drumont in France, depicting a grotesque, power-hungry Jew straddling a globe. The two word caption underneath says, “Their homeland”.

How else, then, to explain their ability to achieve “disproportionate influence” in key sectors of society, be it in prewar Germany or contemporary America, other than by their treachery? To those who malevolently seek explanation, justification, or distraction, such trigger words as “Jew”, “Yid”, “Hebrew” or, in the modern era, “Zionist” or “Israeli” can offer an irresistible temptation, with the foreknowledge that there is likely to be a ready-made audience that picks up the charge and runs with it. After all, how many people have been conditioned to believe any and all accusations against the Jewish people and, since 1948, the Jewish state?

And to match the wicked intentions, Jews must be depicted accordingly: caricatured, demonised, vulgarised. They need to be portrayed as short, hunched, ghoulish, gnarled, hook-nosed, beady-eyed, secretive, avaricious, sinister, mysterious, animalistic, donkey-eared, spidery, rat-like, blubbery, or otherwise physically repulsive and subhuman.

Because of the Jews’ alleged perfidy, they merit no understanding, much less sympathy. Whatever tragedies befall them are fully deserved. After all, should there be any other fate for unadulterated wickedness?

And if, after the Holocaust, antisemitism got a “bad” name among those who thought the gas chambers and crematoria were a step too far, then the rebirth of Israel offered a new outlet, according to some observers, including Michal Cotler-Wunsh, Israel’s special envoy for combating antisemitism. According to this view, the evil is shifted from the individual Jew to the Jewish nation, together with the projection of every imaginable sin, from genocide to ethnic cleansing, war crimes to child murder. Yet, at the same time, proponents insist that such accusations are anti-Israel, not antisemitic, even as they are transparently transferable tropes from long-held antisemitic beliefs and have no relation to the truth.

At heart, then, antisemitism is an irrational, intractable set of views about an entire group of people. Facts alone are unlikely to cure the disease. As the Irish author Jonathan Swift wrote centuries ago, “You cannot reason a person out of a position he did not reason himself into in the first place.”

Why are Jews sometimes referred to as “the canary in the coal mine”?

For miners, having a canary along in the coal mine was a matter of life and death. If carbon monoxide, which is odourless and colourless, was present, the canary would feel it well before the miner, in fact dying as an alert to the miner to get out immediately.

Jews have often been cast by the world in essentially the same role as the canary. When antisemitism rises and Jews’ anxiety level grows, it is a warning sign that something bigger and broader is amiss. It may first affect Jews, but left unchecked it will threaten society as a whole, be it other minorities, respect for human dignity, or broader democratic values.

Some Jews, however, reject the description of the canary in the coal mine not because it is inaccurate but because they say they are unwilling to continue to die from society’s poisonous carbon monoxide, in this case antisemitism, so that others might have the chance to live.

Anti-Zionism as Antisemitism

In November 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to recommend that separate Jewish and Arab states replace the British Mandate. The Arab world categorically rejected the plan. Notwithstanding, the Jews announced the establishment of Israel on May 14, 1948.

Since then, many believe that a new form of antisemitism has emerged: anti-Zionism. Rather than focus on the individual Jew or Judaism or the Jewish “race”, the target is the Jewish state. Its exponents often claim their rejection of Israel is not antisemitic but rather state-driven. Others insist the two cannot be separated. Is calling for Israel’s destruction inherently antisemitic? Does any attempt to compare Israel’s actions to those of Nazi Germany or apartheid South Africa cross a line into antisemitism? Does treating Israel differently at the UN compared to other member states constitute antisemitism? If Israel’s overseas supporters are accused of “dual loyalty”, meaning their loyalty to Israel is seen as in conflict with loyalty to their country of citizenship, is this antisemitism?

When does criticism of Israel become antisemitism?

Natan Sharansky was a leader of the Jewish and human rights movements in his native USSR. He was arrested for his activities and sent for nine brutal years, 1977– 86, to the Soviet Gulag, where he became one of the world’s best-known political prisoners. He was finally allowed to leave the USSR in 1986 and resettled in Israel. Fifteen years later, he was the Israeli minister of diaspora affairs. As he said at the time, while witnessing a surge in antisemitism starting in Europe, he “was grappling with the question of how to distinguish between legitimate criticism of Israel and antisemitism.”

He came up with a formula, known as the 3D test, that has been widely used by mainstream Jewish organisations and various Israeli governments. Here is his explanation:

These 3Ds – demonisation, delegitimisation and double standards – are the three main tools that antisemites employed against Jews throughout history.

For thousands of years, Jews were demonised, they were charged with blood libels, with poisoning wells, and, later, with controlling the global banking system. The Jewish faith and the Jewish claim to nationhood was delegitimised.

And double standards were applied to Jews, either through the imposition of special laws – from the Middle Ages in Europe, to the Russian Empire and Nazi Germany – or through de facto government policy discriminating against Jews, as I experienced in the Soviet Union. Throughout history, demonisation of Jewish people, delegitimisation of their faith or nationhood, and double standards applied to Jews created fertile soil for pogroms, expulsions and genocide.

My 3D test shows that if we see these same tools of delegitimisation, demonisation and double standards that were used against Jews in the past being used against the collective Jew, the Jewish State, today – we know we are witnessing a new face of the old antisemitism.

What is the role of a nation’s leaders with respect to antisemitism?

There are three basic responses on the leadership level: fanning the flames of antisemitism, confronting it head-on, or downplaying or ignoring it. In the first category, there are several examples in recent history.

When Pope John Paul II visited Syria in 2001, he was greeted by President Bashar al-Assad, who, speaking to the world’s media, said: “They [the Jews] try to kill the principle of religions with the same mentality they betrayed Jesus Christ and the same way they tried to betray and kill the Prophet Mohammad.” While the pontiff, for whatever reason, did not react in the moment, the Israeli President later responded by calling Assad’s words “careless, racist, antisemitic”.

Long-serving former Malaysian PM Mahathir Mohamad believed Jews pose a global threat, even though none were present in his country (Image: Shutterstock)

During his two terms of office, from 1981 to 2003 and 2018 to 2020, Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad of Malaysia was accused on multiple occasions of promoting antisemitism. Indeed, his bigotry was revealed as early as 1970, when he wrote an essay titled “The Malay Identity”, in which he exclaimed, “The Jews are not only hooked-nosed… but understand money instinctively… Jewish stinginess and financial wizardry gained them the economic control of Europe and provoked antisemitism which waxed and waned throughout Europe through the ages.”

In 1984, he prevented a scheduled visit of the New York Philharmonic to Kuala Lumpur because the program included a piece by a Swiss Jewish composer, Ernest Bloch, inspired by a Hebrew melody. And in subsequent years, he invoked many of the classic antisemitic tropes about Jews and control of the media, Jews and financial thievery, and Jews and plots to undermine his country. Incidentally, this was a striking example of antisemitism without Jews. There is no Jewish community in Malaysia, but, to Mahathir, Jews pose a global threat, irrespective of whether they are physically present in a country – and despite the fact that Jews, in total, comprise 0.2% of the world population, or one in every 500 people on the planet.

In 2010, in a particularly noteworthy development, longtime Cuban leader Fidel Castro, a staunch Communist, publicly accused the President of Iran, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, of antisemitism for, among other reasons, denying the Holocaust. Castro told the Atlantic magazine, “The Jews have lived an existence that is much harder than ours. There is nothing that compares to the Holocaust… I don’t think anyone has been slandered more than the Jews. I would say much more than the Muslims. They have been slandered much more than the Muslims because they are blamed and slandered for everything. No one blames the Muslims for anything.” In the same interview, Castro recalled his childhood: “He reminisced about being a young boy and overhearing classmates saying Jews killed Jesus Christ. ‘I didn’t know what a Jew was. I knew of a bird that was called a ‘Jew,’ and so for me the Jews were those birds. This is how ignorant the entire population was.”

Then there is the case of Jeremy Corbyn, leader of Britain’s venerable Labour Party from 2015 to 2020 and candidate for prime minister in the 2019 national election.

Corbyn was frequently accused of antisemitism during his tenure, as well as countenancing antisemitism in the party’s ranks. Britain’s Equality and Human Rights Commission issued a blistering report of that period in 2020: “The investigation was prompted by growing public concern about antisemitism in the Labour Party and followed official complaints received by us… [O]ur investigation found significant failings in the way the Labour Party has handled antisemitism complaints over the last four years. We found specific examples of harassment, discrimination and political interference in our evidence, but equally of concern was a lack of leadership within the Labour Party on these issues, which is hard to reconcile with its stated commitment to a zero-tolerance approach to antisemitism.”

Former UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was found to have allowed antisemitism to flourish in his party by the British Equality and Human Rights Commission (Image: Shutterstock)

Again, it needs to be stressed that the leader of the party under investigation by this politically neutral body was vying for occupancy of 10 Downing Street and was the runner-up in the 2019 election. The report illustrated the constructive role that such a commission can play in a democratic society. After its release, Corbyn did step down, to be replaced by Sir Keir Starmer, who pledged a “zero-tolerance approach to antisemitism and racism.” In 2024, Starmer became Britain’s prime minister.

In 2024, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro, in an election many believe he manipulated, tried to divert attention away from himself and point the finger at Zionism (in other words, Jews). He said Venezuela’s “extremist right” is “financed” and “supported by international Zionism,” claiming that “all the communication power of Zionism, which controls all social networks, the satellites, and all the power, is behind this coup d’état.”

By contrast, there are examples of a country’s leaders standing clearly and unambiguously against antisemitism. Does it help? No guarantee, but at the very least it sends the right message to a nation, all the more so if reinforced by actions that back up the words and have some teeth.

After the rape of a 12-year-old Jewish girl in June 2024, which was reportedly accompanied by antisemitic slurs by the three perpetrators, French President Emmanuel Macron minced no words in speaking of the “scourge of antisemitism” plaguing France and urged all schools to devote time to a dialogue about racism and antisemitism. Whether such school discussions take place, including how antisemitism and racism are juxtaposed and addressed, and with what results, remains to be seen, but, again, it reflects a recognition that condemnations of antisemitism alone are woefully inadequate to address the growing threats around the world.

In the face of rapidly rising antisemitism in the United States, President Joe Biden not only forcefully condemned it but also, in 2023, issued the comprehensive US National Strategy to Counter Antisemitism, the first of its kind in American history. In a statement at the launch of the groundbreaking initiative, Biden announced that “it represents the most ambitious and comprehensive US government-led effort to fight antisemitism in American history.”

During Austria’s rotating presidency of the European Union in 2018, Chancellor Sebastian Kurz successfully pressed for EU member states to adopt national strategies to combat antisemitism, based on the key dimensions of education, security, law enforcement, integration, documentation, and civil society.

Elsewhere in this book, reference was made to the initiative of the 35-nation International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, formalised in 2016, to create a standardised definition of antisemitism, including seeking to confront the complex issue of when criticism of Israel spills over into antisemitism. After all, in order to combat antisemitism, some common understanding of what it is (and is not) is needed.

And as a final example of leadership, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution in 2005, however late in coming, designating January 27, the day in 1945 that Soviet troops liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau, as International Holocaust Remembrance Day. UN commemorations, as well as events in some countries, have taken place since. In the resolution, any attempt at Holocaust denial was strongly condemned.

At the same time, the UN does not have enforcement power and, being such a highly politicised institution, has not always been able to ensure that the original measure would be used as intended by its sponsors. Nonetheless, it offers an example of recognising the need to go beyond ritualistic condemnations of antisemitism and, in this case, mobilise education and remembrance as ongoing tools to fight it.

As for the third category of leadership response, let’s call it the middle ground, this clearly falls short. In 1995, Father Henryk Jankowski, a parish priest in Gdansk, Poland, delivered a fiery sermon that included an attack on Jews. He asserted, “The Star of David is implicated in the swastika as well as in the hammer and sickle.”

While these words were not new for him, what elevated the mass to a global news story was the presence in the church that day of Polish President Lech Wałęsa – and his failure to react either during the service or for the next nine days, until he finally denounced antisemitism, but without any reference to the offender in this case.

In a subsequent meeting with an AJC delegation in San Francisco during the 50th anniversary celebration of the UN founding, Wałęsa defended his long silence by asserting that anything else would have only brought more attention to Jankowski’s bigotry. By contrast, the AJC group argued that, by staying silent for as long as he did, he sent the wrong message to his nation of 35 million people. As one Jewish participant in the meeting said, “Two totally different interpretations. No meeting of the minds.” Did this story suggest that Wałęsa himself was sympathetic to antisemitism? Not necessarily, but it certainly raised questions for many.

In 2001, as antisemitism erupted in France, home to Europe’s largest Jewish community, and as rabbis told religious Jews that taking off a kippah or hiding it under a baseball cap was now permitted for safety reasons, AJC met with President Jacques Chirac in his office. The aim was to alert the French head of state to the growing threat and enlist his help. His response: “I know my country better than you. There is no antisemitism in France.”

Chirac was not an antisemite. Indeed, as noted, he had been the first French leader to acknowledge that Vichy collaboration with the Nazis, including in the roundup and deportation of Jews, was part and parcel of French history and could no longer be denied. Yet he was unwilling to acknowledge what had become painfully obvious – that French Jews were fearful for their safety due to intimidation and threats from the country’s growing Arab and Muslim population, which dwarfed the Jewish community by a ratio of 10 to 1. In a later meeting with Foreign Minister Hubert Vedrine, in November 2001 in New York, the same group again tried to raise alarm bells, but once more without success. The chief diplomat’s reply: “There is no antisemitism in France. Instead, there is hooliganism and also the regrettable importation of the Arab-Israeli conflict onto French soil.”

This inability, or unwillingness, to see the rising menace of antisemitism, which after all was not a new or foreign disease in France, delayed the awareness of its magnitude. As a consequence, the state failed to reach out to an increasingly anxious community wondering if its place in France was still assured, as well as the opportunity to formulate a timely national strategy while there was still a chance to nip it in the bud.

In Hungary, President Viktor Orbán has been accused of antisemitism, particularly depicting his political nemesis, the Hungarian-born financier George Soros, in ways that evoke antisemitic tropes – distorted features, money bags, devious plots to sabotage the country – whenever there is an election, not to mention trying to idealise Hungary’s less-than-perfect record in the Holocaust.

Orbán’s defenders argue that Hungary is home to the largest Jewish community in Central Europe, and that Orbán is one of Israel’s staunchest allies in the European Union and at the UN. So, which is he, or is he cunningly both? Certainly each side believes the facts are with them.

Poster from Hungarian political party Fidesz showing the opponents of PM Viktor Orban surrounding Jewish billionaire philanthropist George Soros (Image: Shutterstock)

As a final example of this middle space, there was the neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, when repeated chants of “Jews will not replace us” were heard. President Donald Trump’s first reaction was “We condemn in the strongest possible terms this egregious display of hatred, bigotry and violence on many sides, on many sides.” Shortly afterward he spoke again: “You had some very bad people in that group, but you also had people that were very fine people, on both sides.”

That led Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, a fellow Republican, to comment, “It sounded like a moral equivocation or, at the very least, moral ambiguity when we need extreme moral clarity.”

Some concluded that Trump was an antisemite by appearing to take a two-handed approach, even as he later sought to dispute that interpretation of his remarks.

Others hastily pointed out that he has always had good friends in the Jewish community, is a grandfather to three Jewish grandchildren, and was one of Israel’s best friends ever in the White House.

For those who are genuinely concerned about antisemitism, whatever its source, the response must be quick and unequivocal, and it needs to mobilise the power of government to stand unflinchingly against such hatred. Anything less sends mixed messages to the general public and the organs of state and, however unintentionally, offers wiggle room to potential perpetrators.

Are there positive examples of action against antisemitism?

As discussed earlier, in the Second World War there were shining examples. They were too few to save six million victims of the Holocaust, but they demonstrated what a belief in shared humanity – and the courage to act on it – could accomplish. Their common denominator was that they did not see Jews as somehow the “other”, the “alien”, the “stranger”, but rather simply as fellow human beings.

And, ultimately, returning to the earlier question of whether there could ever be a “Pfizer vaccine” to inoculate against antisemitism, or perhaps even intolerance more broadly, the admittedly utopian answer lies in seeking to educate in homes, classrooms, houses of worship, the political arena, the worlds of sports and culture, and our public spaces – and not just in one lesson plan, one sermon, one speech, one gesture, but consistently and in real-life behaviour – genuine respect for one another.

Not tolerance. That sets the bar too low. The aim should be not tolerance for one another but rather appreciation for those of different backgrounds. In other words, affirming one’s own identity should not have to come at the expense of denigrating or denying someone else’s.

Those Second World War rescuers put themselves on the line to protect fellow human beings and affirm the kind of world in which they wanted to live.

As Dr Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1962, “We must learn to live together as brothers or we will die together as fools.” And as the Hebrew Bible states, “God created humankind in God’s image.” No hierarchy. Universal equality. All the major religions have a variation of the Golden Rule – “Love thy neighbour as thyself,” in the Christian tradition – embedded in their teachings. The age-old challenge has been to put these noble visions into daily practice.

One community that did so was in the city of Billings, Montana. In 1993, some White supremacists and admirers of the Ku Klux Klan moved into town. In December, during the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah, a cinder block was thrown through the window of a small child’s bedroom, where a holiday menorah was displayed. Luckily, the child, Isaac, was in another room at the time. But the incident, following other threats to the tiny Jewish community, galvanised the city into action.

Led by the Executive Director of the Montana Association of Churches, the publisher of the Billings Gazette newspaper, and the chief of the Billings Police Department, together with Isaac’s mother, Tammie Schnitzer, the city made available paper menorahs and encouraged residents of all faiths to display them prominently. The message to the haters: The Jews were no longer few in number. They now had thousands of allies. The minority had become the majority. The tables had been turned on the antisemites. In the end, those extremists vanished.

The police chief early on reacted to the hate mongers in Billings: “Silence is acceptance. These people are testing us. And if we do nothing, there’s going to be more trouble. Billings should stand up and say, ‘Harass one of us and you harass us all.’”

Maybe the millennia-long search for the end of antisemitism is, in reality, as straightforward as that: communities of goodwill everywhere banding together and saying loudly to the world “Harass one of us and you harass us all.”

© David Harris. Extract from Antisemitism: What Everyone Needs to Know® published by Oxford University Press in November 2025 (US), February 2026 (UK), March 2026 (AUS) – available in hardcover, paperback and eBook formats, $34.95 AUD PB.

David Harris, a lifelong Jewish activist, led the American Jewish Committee (AJC) – described by the New York Times as the “dean of American Jewish organizations” – from 1990-2022. He was referred to by the late Israeli President Shimon Peres as the “foreign minister of the Jewish people.” Harris has been honoured more than 20 times by foreign governments for his international work, making him the most decorated American Jewish organisational leader in history.

Tags: Anti-Zionism, Antisemitism, Israel

RELATED ARTICLES

US Middle East strategy amid regional instability: Dana Stroul at the Sydney Institute