Australia/Israel Review

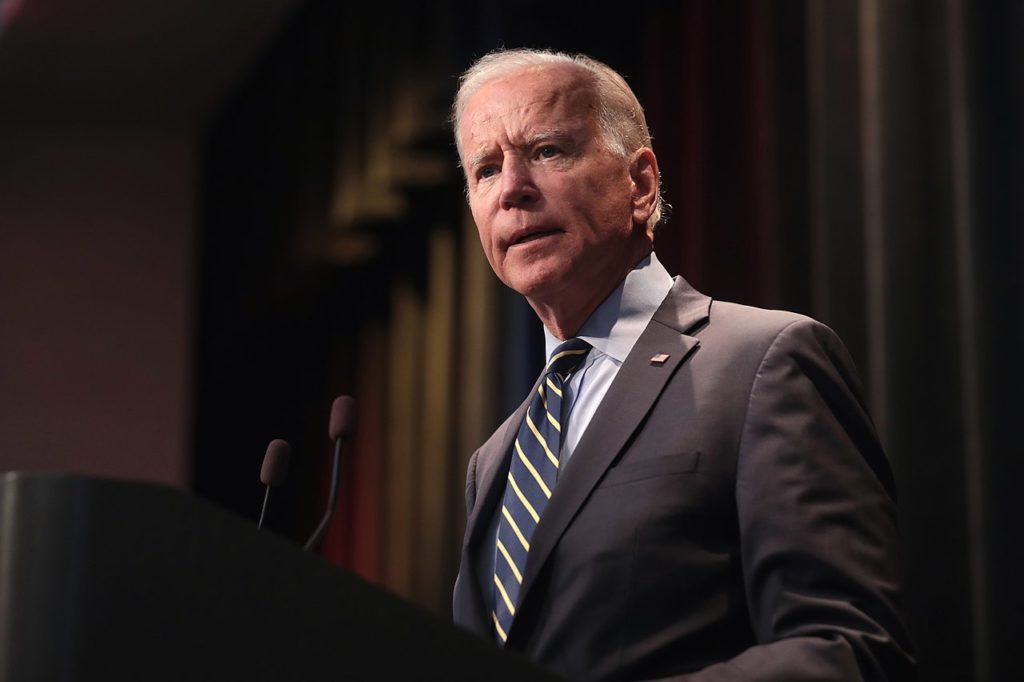

Biden’s Iran policy needs more sticks

Apr 6, 2021 | David Pollock

There is good news and bad news regarding the Biden Administration’s policy toward Iran so far. The good news is that, as promised, this team – unlike the Obama one that most of them were previously part of – seems focused almost as much on Iran’s non-nuclear activities as on its nuclear ones. The bad news, however, is their actual policy toward those non-nuclear challenges is mostly carrots, and very few sticks. The result, no doubt unwittingly, is that the US is emboldening and empowering Iran on the Mideast regional level, rather than containing it.

To be fair, let us first consider the sticks against Iran’s regional threats that the Biden team have employed to date. They carried out one retaliatory strike against an Iran-backed militia in Syria, after its lethal attack against American targets across the border in Erbil, Iraq; and they have upped US anti-missile defences in Saudi Arabia in the face of continuing attacks by the Iran-backed Houthis (and probably others) across that border. The other actions taken against Iran and its local allies have been almost purely rhetorical or symbolic: sanctioning a few individuals; overflying a few B-52s; or just threatening to take real action at some unspecified future date.

Now for the carrots. The Biden Administration has removed Yemen’s Houthis from the official list of designated Foreign Terrorist Organisations, with no conditions or concessions in return. It has supported the first formal visit to Teheran by the UN Special Envoy on Yemen, to discuss the fate of that country behind the back of its own internationally-recognised Government. Similarly, the Administration has also formally proposed to include Iran in an international conference on the future of Afghanistan, over the head of the supposedly US-allied Afghan Government.

One cannot help but wonder who’s next on this list. How about inviting Iran to discuss the future of Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, thereby legitimising its militias in all three countries? Why not allow the terrorist Hamas movement, Iran’s potential Palestinian proxy against Israel, to run in a West Bank/Gaza election scheduled for May 22? This approach has all the hallmarks of the “inclusive” or “comprehensive” regional negotiations or conflict-management tactics that some of Biden’s key mid-level policymakers have long advocated before, in or out of government.

To be fair again, there may be times when such an approach could be useful. In the case of Iran specifically, there was a very brief window almost two decades ago, in 2001-03, when a US diplomatic outreach to Teheran did prove helpful, in Afghanistan and to a lesser extent in Iraq. Today, however, there is no sign that Iran is prepared to contribute constructively, or even to reduce its destructive meddling, in any of these regional conflict arenas.

Nevertheless, the Biden Administration is perceived, rhetoric aside, to be passively relaxing sanctions against Iran. One relevant mid-level official claims that “the President” will not make any “substantial” or “unilateral” moves to ease sanctions against Iran. But it doesn’t take an expert to drive billions of dollars through the loopholes in those carefully crafted words.

Finally, to be fair one more time, it is admittedly easier to criticise a weak policy than to come up with a stronger one. So here is a modest proposal: instead of proffering free carrots to the regime in Teheran, the US should adopt a clear transactional stance, one that effectively combines the nuclear and non-nuclear files. If, for example, Iran can convince the Houthis and other militias to stop their missile and drone attacks against Saudi Arabia, then and only then will Washington offer Teheran any sanctions relief whatsoever – regardless of whatever concessions Iran may be willing to offer on its ongoing violations of the 2015 nuclear deal, the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action). To be sure, this short-term strategy may eventually require some refinements. But it is a necessary first step.

This adjustment to current US policy would have several virtues. It would offer Iran a realistic path to compromise, but not a free ride. It would reassure US allies – Arabs, Israelis, and even some Europeans – that the US is again a reliable partner. And it would help fulfil the promises that the Biden team has made: to take those allies more seriously; to deal with Iran’s non-nuclear as well as its nuclear threats; and to address, as they never tire of repeating, the regional realities of today, rather than the aspirations of a previous political era.