Australia/Israel Review

Biblio File: The Education of an Editor

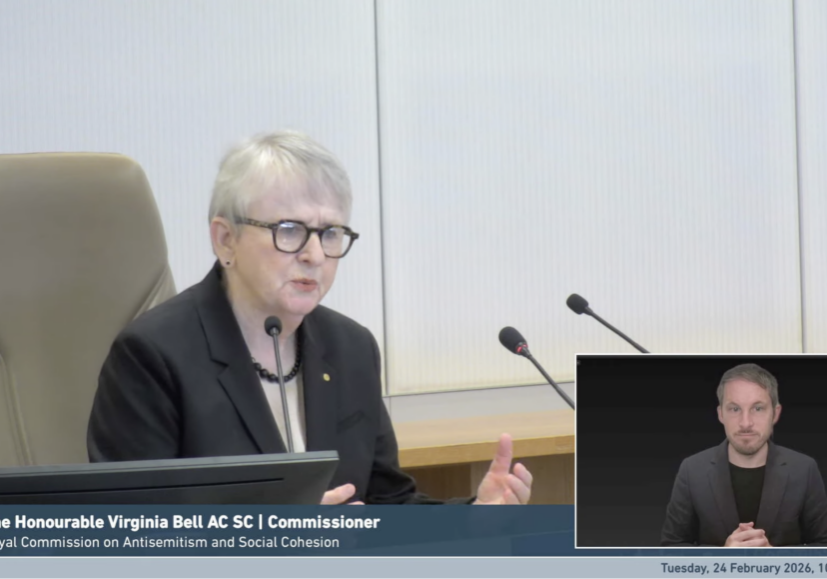

Mar 28, 2024 | Allon Lee

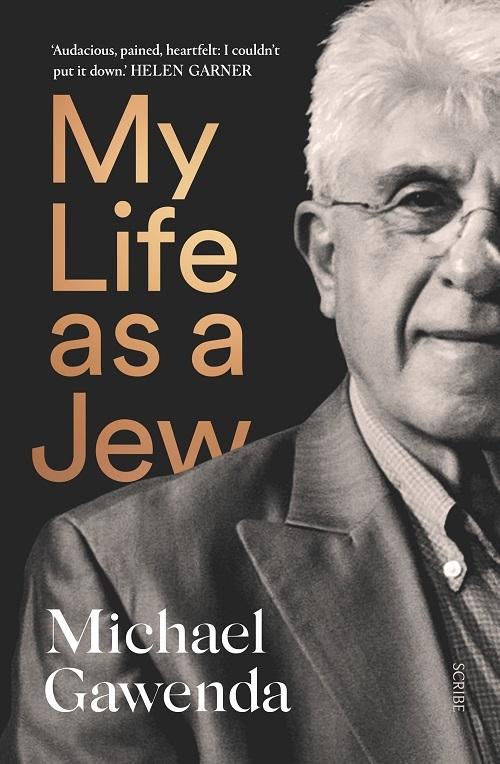

My Life as a Jew

My Life as a Jew

by Michael Gawenda

Scribe, October 2023, 288 pp., $35.00

Former Melbourne Age editor Michael Gawenda’s memoir, My Life as a Jew, is a case of cometh the hour, cometh the author.

The timeliness and importance of this new book cannot be overstated.

In the book, Gawenda documents his growing recent alienation from his ideological home on the Left, which has turned against Israel and Jews who support it, meaning most of world Jewry.

A three-time Walkley Award winner, he examines the historical processes that have led to this fissure and does so in an Australian context, which is a rarity.

Published mere days before October 7, it loses nothing from its release on the cusp of this horrific event.

Denied the advantage of 20-20 hindsight, Gawenda’s analysis of the direction the cultural, political, social and ideological winds were blowing came to be tested more or less in real-time – and proved prescient.

The book covers the length and breadth of Australian stakeholders who involve themselves in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, including politicians, journalists and academics.

Among those it locks horns with are high-profile anti-Zionist Jewish publisher Louise Adler, crusading ABC journalist John Lyons, and the Israel lobby-obsessed former Australian foreign minister Bob Carr. Many of these same individuals have been prominent in public debate since October 7.

The corrosive effect activist journalists are having on balanced and professional coverage of the Middle East is also canvassed.

By interweaving his personal experiences with the political, Gawenda, a skilled writer and keen observer, never lets the reader’s attention flag.

A child of Holocaust survivors, Gawenda was born in a displaced person’s camp in Linz, Austria two years after WWII ended.

His parents were Bundists – a Jewish movement that believed Jews would be better off in a world built on socialism, secularism, internationalism and opposition to Zionism.

Yet even when antisemitism appeared to be in retreat after the Holocaust and Jews exercised sovereignty for the first time in 2,000 years, Gawenda appears to have intuited that the world remained a cold place for Jews.

Early on, he declares, “I spent a lifetime determined not to be a Jewish journalist. I now think that was a mistake. It was as if I were hiding the fact that I was a Jew.”

This epiphany arrived rather late in his long career, during his seven-year stint as editor of the Age (1997-2004).

It didn’t matter if non-Jewish colleagues agreed or disagreed with his editorial choices regarding Israel, there was always a perception that his decisions were not informed by decades of journalistic experience, but instead by his Jewishness. The primary example he gives comes from 2002, when he blocked publication of Michael Leunig’s cartoon that compared Israel’s counterterrorism operation in the Palestinian city of Jenin during the Second Intifada with Auschwitz.

Gawenda bristles at being pigeonholed this way, adamant that there is no contradiction between being Jewish and following the principles of professional journalism.

This speaks to one of the book’s major themes: the contortions and compromises Jews make to fit in – both on the left and the right – and how they frequently still result in rejection. As he notes, “in Stalin’s purges – Jews who had given up their Jewishness… were murdered because they were Jews.”

It also speaks to his frustration with the blind spot of anti-Zionists, particularly Jews, who he sees as remaining indifferent to the reality that “the virus of anti-Semitism is loose in the world.” Exhibit A is Louise Adler.

The collapse of his friendship with Louise Adler kickstarts the book. This is not merely because the story is so dramatic – it is also the reason Gawenda ended up writing his book in the first place. Once he started to analyse the fallout from that event, he couldn’t stop.

The backstory to his decision to terminate his contact with Adler was their discussion of the “dobetteronpalestine” open letter from May 2021 that called for journalists to prioritise the Palestinian narrative and to also be able to express solidarity with the Palestinians without being professionally penalised.

He comments that the letter does not say which “Palestinian perspectives should be prioritised” and asks if that would include Hamas, “which advocates the violent elimination of Israel.”

He was also unsettled by “journalism academics, people who train journalists” signing the letter and chides the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance, which represents the interests of media professionals, for endorsing the rights of its members to act as advocates for the Palestinian cause.

Gawenda says he pointed all this out to Adler and was stunned to learn she subsequently commissioned former Middle East correspondent and now ABC Global Affairs Editor John Lyons to write his pamphlet Dateline Jerusalem: Journalism’s toughest assignment.

The central theme of Lyons’ short monograph is the claim that the Israel lobby, which he falsely claims is far-right, pro-settlement, pro-occupation and against the two-state formula for peace, intimidates journalists and editors to adopt a pro-Israel editorial line and self-censor.

According to Lyons, the lobby does this to prevent Australians from learning the truth about the worst excesses of Israel’s occupation of the West Bank.

Gawenda is having none of this. He ridicules Lyons’ claims that journalists are so supine that simply sending them on all-expenses paid trips to Israel where they drink booze will make them comply. Failing that, the Israel lobby threatens, Lyons suggests, and Gawenda asks with “what – violence? Damnation? Cancellation? – [it] is never clear.”

Gawenda asserts Lyons’ “thesis about powerful Jews making cowards of virtually every editor and executive producer in the country was a conspiracy theory that did not stand up to any real scrutiny.”

Lyons, he says, claimed to have interviewed 23 “editors and senior journalists” on the record but failed to name all but a few and was essentially asking to “be taken at his word. Frankly, I am not prepared to do that.” Gawenda asks why Lyons did not interview him, considering “I was the only Jewish editor” of a major metropolitan paper in Australia during the late Oslo period and Second Intifada.

“Why would Lyons not have spoken to me? Perhaps he thought he might have discovered that I was not a fellow traveller of the Israel Lobby,” he says.

Gawenda was aghast that Adler would endorse Lyons’ agenda, even after they had talked it over, which is why he chose to end decades of friendship with her.

Elsewhere, Gawenda’s account for why the sensible left, i.e. social democrats, “fell out of love” with Israel is well-written but breaks little new ground.

Israel’s territorial gains during its overwhelming victory in the Six-Day War proved it was not “just a vulnerable little nation of socialist pioneers surrounded by enemies. It was powerful and flawed.” The process accelerated when the Likud broke the left’s stranglehold on power in 1977 and continued through the 1980s as the Israeli right became “ascendant”.

The two Bobs – Hawke and Carr – are prime examples of two centre-left figures who started off as strong supporters of Israel but grew disillusioned, he writes.

Both men “came to understand, painfully, with regret, and, in Carr’s case, with hostility and bitterness, that Israel … could never be, the nation that embodied their socialist dreams.”

There is much more that comes under Gawenda’s steely gaze, including the left’s campaign to whittle away at how antisemitism is defined, so the term can only refer to anti-Jewish hate that originates on the right.

Concomitant with this is the attempts made to remove the Jewish specificity of the Nazi’s genocide of six million Jews in the Holocaust, something both the left and right are complicit in. As Gawenda writes, the Holocaust has become “universalised”, as though it “could have happened to anyone, and it was random bad luck that it happened to Jews.”

Ahead of the book’s publication, Nine Newspapers excerpted parts of the Adler chapter.

Since its publication, Gawenda has contributed many analyses, but all bar one has run in what Gawenda would once have regarded as the ideological competition – the Australian.

Thankfully Gawenda has not been a lone voice in the wilderness holding the media’s feet to the fire.

Other Jewish journalists, including former Age columnist Julie Szego and former ABC journalist Ramona Koval, have raised their heads above the parapet too.

In a world flooded with anti-Israel polemics, My Life as A Jew is a much-needed and long overdue corrective from a lucid, highly experienced and impeccable source.